After years of crippling drought, Namibia’s Kunene Region is stirring back to life. Desert-adapted wildlife is returning and local conservationists are working to secure a brighter future for people and nature alike. Gail Thomson returns to the region and is heartened by what she finds: desert wildlife rebounding, communities rebuilding, and recovery in this stark but spectacular region.

Namibia’s Kunene Region is home to famously desert-adapted wildlife that lives alongside the Ovahimba, Ovaherero and Damara people. This area is almost entirely covered by communal conservancies, many of which have been operating for over 20 years. The last ten years have been a challenging time for the people and wildlife sharing this landscape due to widespread drought.

During a trip in early March this year, my husband and I witnessed the effects of this multi-year drought, as the rocky desert landscape looked harsh and barren. This all changed with good rains in April and May 2025 – the best the Kunene has received in many years. We decided to organise another trip in July to see how the rains had transformed the landscape, and to find out how the wildlife and people in communal conservancies are faring.

What we found were signs of a new dawn for the region. Wildlife is starting to repopulate the area, while dedicated community conservationists are finding ways to support their recovery.

Finding life in the desert

The key to understanding the Kunene is an expert guide. While anyone with a 4×4 vehicle can explore the Kunene Region on their own, few will see beyond the landscape to understand wildlife movements and human behaviour in response to the recent rains. We therefore met up with Boas Hambo, a local expert in the Kunene Region, to gain deeper insights.

Boas is part of a new generation of African conservationists who are bringing African perspectives and ideas to a field that non-Africans have historically dominated.

We approached the semi-arid Kunene Region from the west, via the stark true desert of the Skeleton Coast. While these gravel plains host many forms of life, not much of it can be seen while driving. Only after travelling inland for nearly 50km did we start encountering patches of yellow that could conceivably be grass. As we drove, the tiny tufts gave way to fully grown grass plants that had turned from green early in the wet season to their yellow winter form.

The grass was a welcome sight, clothing the red rocks in a gossamer cloak that thickened to a fluffy carpet in areas that received excellent rainfall. Such abundant grass is beautiful, yet it shows that there are few grazing animals left to eat it. Many cattle have died in recent years, leaving livestock-dependent communities destitute and hungry. “Milk is an extremely important part of the diet out here,” says Boas. “When we run out of maize meal, we survive on cups of milk from our cattle and goats.” But milk becomes scarce when the cattle are all dead, and goats and sheep are barely clinging to life.

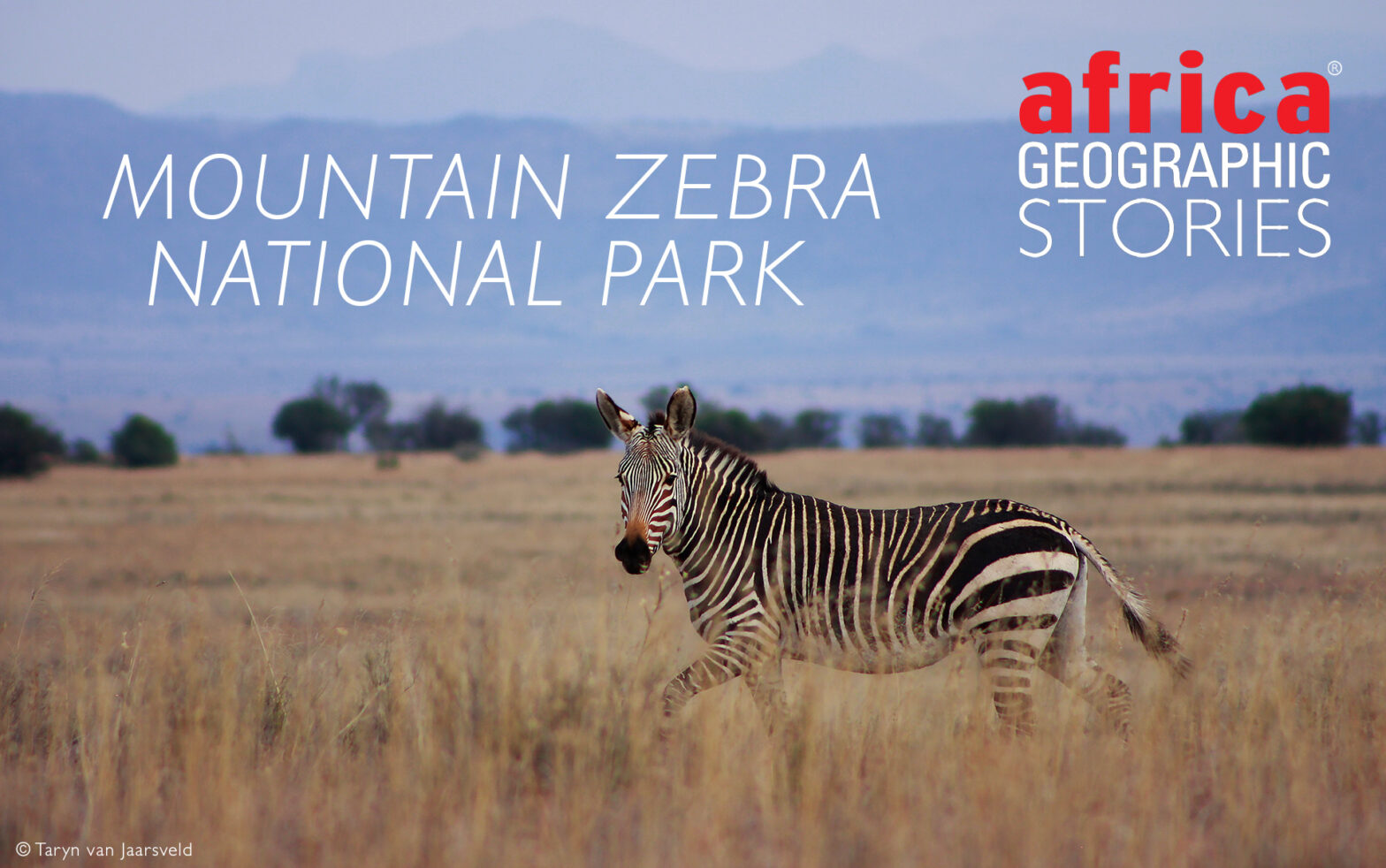

Unsurprisingly, wildlife numbers have been dropping each year during the drought and are now very low, according to annual game count figures. These game-count trends reflect both real population decreases and movement. “Each animal has a different way of dealing with the drought – for example, the Hartmann’s mountain zebras move into the inaccessible mountainous areas during drought in search of natural springs and grazing that is not accessible to cattle,” Boas tells us.

He also suggests that now that the drought has broken, the gemsbok will spend more time in the true desert to the west, where there is still grass and plenty of gemsbok melons – fleshy desert fruits that gemsbok love. Since the game counts take place by road and do not cover the coastal desert or the inaccessible mountains, it is difficult to say precisely how many gemsbok and zebras have died in the drought versus how many have moved.

What we do know, courtesy of a giraffe-specific monitoring programme by Giraffe Conservation Foundation, is that giraffe numbers have remained stable during the drought years. As specialist browsers, the giraffes do not need grass, although they will benefit from fresh leaves after the rains. On our trip, we saw baby giraffes in nearly every herd we encountered, indicating that their population should grow. Surprisingly, giraffes do not need to drink water – although they drink readily when water is available, they can obtain all the moisture they need from leaves alone.

And Boas is optimistic: “I saw many more animals during the conservancy game count this year than in previous years, although the official statistics for the whole count aren’t out yet.”

Want to visit Namibia on safari? Browse our top Namibia safaris. Or, check out our safaris to other destinations.

Want to visit Namibia on safari? Browse our top Namibia safaris. Or, check out our safaris to other destinations.

Getting to know Boas, our Kunene guide

During our many hours on the road exploring, we got to know Boas’s backstory. Like many young Herero and Himba boys growing up in the 80s, Boas was sent to look after goats at an age when most urban children start attending primary school. Although he started school later than most, he seized his opportunity for education with both hands. As a teenager, he took a job with Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC).

Boas flourished with IRDNC and was promoted from general camp-hand to trainer of community game guards. After that, he worked with the Community Rhino Rangers Programme to counter the threat of black-rhino poaching in the communal conservancies. He now works for Conservancy Safaris Namibia, leading multi-day expeditions that explore the Kunene Region. As a result of his work, he has spent many hours on the road with numerous conservation stalwarts, including Garth Owen-Smith, Dr Margaret Jacobsohn and Russell Vinjevold – mentors who provided different perspectives and experiences on conservation and tourism.

During his varied career, Boas has followed desert-adapted lions for weeks on end, patrolled thousands of square kilometres to monitor and protect black rhinos, assisted conservancies to develop and implement natural-resource management plans, and introduced international guests to the vast wilderness he calls home. He has not forgotten his farming roots, however, and still keeps livestock near his home in Warmquelle, Kunene.

In short, there are few people alive today who possess such a deep understanding of local culture and farming practices, animal behaviour, practical nature conservation and the role of tourism in the Kunene Region. His perspective on the wildlife we saw and the conservation concepts we discussed enriched our journey and added meaning to our observations.

Elephants and lions in the famous Hoanib River

Unlike giraffes, elephants are heavily dependent on water and therefore greatly affected by the drought. In Kunene, the herds have been increasingly restricted to the dry riverbeds, where natural springs and artificial waterpoints quench their thirst. The giant Ana trees provide nutrient-rich pods, while riverine vegetation survives the drought better than outside the riverbed.

The restrictions that drought places on elephant movement and nutrition nonetheless take a toll. Elephant calves suffer the most during drought. Half of the calves in this far western population died within their first year during 2023, according to a report from Desert Elephant Conservation. Female elephants that are barely meeting their nutritional requirements will not readily come into oestrous, and those that do have calves may not produce enough milk to sustain them.

On our trip down the Hoanib River, a stronghold for desert-adapted elephants, we saw some of the new babies of the season. “I counted 14 baby elephants in the Hoanib earlier this year,” says Boas, “it seems that we are now in a ‘baby boom ’ and I hope that this population will continue to grow.” These elephants are a key tourist attraction for the few lodges in the Hoanib Valley.

That night, we camped outside the riverbed at one of the bush camping sites. This site is far enough away from the river to be safely out of the way of the wildlife – including hungry lions. During a drought, lions can benefit from staying in riverbeds and near waterpoints, knowing that their prey will have to come to them. When the drought breaks, however, lions find themselves in a precarious position. The prey species spread out to take advantage of the widespread grazing and natural water sources. When the overall population is as low as it is now, hunting becomes very difficult.

The lions have adapted to this situation in several ways, some of which are fascinating for research, while others are concerning from a human-lion conflict point of view. In the Hoanib River, the lions started specialising in giraffe hunting, which became the most common prey animal available. On our trip, we found the male lion known as “OB” feeding on a giraffe that he had killed the night before.

We heard this good news long before we found the lion, since we encountered Allu Jauire Uararaui – a human-wildlife conflict specialist for Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation under Russell Vinjevold – soon after entering the river valley. Boas and Allu are old colleagues, and Allu readily agreed to us following him to the lion and its kill. They have been watching this lion’s movements via its satellite collar for months, and were mainly concerned when it left the Hoanib and started roaming near human settlements. “This male lion is significant, since he is the only adult male left in this area”, explains Allu, “so I came out here to check that he was back in the riverbed and not out in the village lands.”

Managing these lions is a delicate balancing act, one which Boas and Allu know all about. Boas had followed the female lion known as “Charly” for a whole month while assisting a Japanese film crew. Tragically, she killed well-known Namibian businessman, Bernd Kebbel (who generously supported the conservation of desert lions), when he exited his tent during a night in the Hoanib River a few weeks before our visit. The authorities promptly euthanised the lion due to the danger she presented to both tourists and locals.

Besides the male lion we encountered and Charly, the other desert-adapted lions in the western Kunene have moved to the coast, where they hunt Cape fur seals and other marine life. Dr Philip “Flip” Stander documented the return of lions to the coast and currently focuses his research on how they are adapting to their new diet and surroundings. OB, the lion we saw, is now the pride male in the area, and he joins the lionesses regularly to mate. The current pair of cubs on the coastline is his.

“The lodges and tour operators want to see more lions, which is understandable,” Boas remarked, “yet there is not enough prey yet to support the lions – we need to focus on rebuilding the prey base, while still trying to keep the few remaining lions out of harm’s way.” If prey numbers increase and stabilise, then lions could be reintroduced from populations in the eastern parts of the Kunene, after consultation with the relevant conservancies.

Supporting Kunene conservancies at a critical time

After leaving our bush camp near the Hoanib, we headed north through Puros village, across the Hoarusib River and into Orupembe Conservancy – our destination: Etaambura Lodge – one of my favourite places to stay in Namibia. Etaambura is managed by Conservancy Safaris, and both are owned by five conservancies including Orupembe: Puros, Sanitatas, Okonjombo and Marienfluss.

Conservancy Safaris and Etaambura were founded by Garth Owen-Smith and Dr Margaret Jacobsohn (co-founders of IRDNC), together with friends who accompanied them on multi-day journeys through the region. Their primary purpose was to provide support for the conservancies. Their current community development and conservation efforts are supported through Jamma Communities & Conservation. Their community initiatives included the building of a school, and the ongoing school feeding programme for the village near Etaambura. The lodge also provides cash benefits to the community during the worst part of the drought.

Boas’ primary mission on this trip was to initiate the new project called “Okamutenge”, the Otjiherero word for the small bag tied to the end of the stick that Ovahimba people carry when going on a journey. The Okamutenge Community Conservation Support project will assist the community game guards in doing regular anti-poaching patrols and community outreach visits.

“Now that the drought has broken, the conservancies can start rebuilding their wildlife populations – if they can ensure that poaching is kept to a minimum,” explains Boas. “Since the people living here have lost most of their livestock, the temptation to poach for meat is higher than ever.”

From the early days of the conservancy programme until today, the goal has been to stop poaching rather than catch poachers. This requires developing close relationships with the communities, creating awareness about the value of wildlife through tourism and hunting, and arresting perpetrators when necessary. Community game guards can do this work most effectively, since they know their area and are trusted by their people.

We accompanied Boas and Henry Tjambiru, the assistant lodge manager at Etaambura, to the Orupembe Conservancy office to meet with their game guards. Boas brought with him eight new pairs of boots and enough food for a 10-day foot patrol, marking the start of the Okamutenge project. He would deliver similar supplies to the Sanitatas Conservancy once we had left. If they secure more funding, their support will extend to Puros, Okonjombo and Marienfluss Conservancies.

During the meeting, he explained that Henry would provide transport into the area to be patrolled (either in Orupembe or Sanitatas), and the game guards would do the patrols and provide feedback. Boas would provide them with additional training before the first patrol to ensure they covered the ground efficiently and responded appropriately to suspected poaching incidents. The game guards were extremely grateful for the support, as their conservancy’s vehicle had broken down beyond repair; they had no other way of patrolling the far reaches of their large conservancy.

Hope for the future of Kunene

During our six-day trip into the Kunene, we drove through all of these conservancies and others around them. We saw giraffe and springbok herds throughout the landscape, and the elephants and OB the lion on the Hoanib River. We also encountered a gemsbok, zebra and ostriches (including one flock of young ones accompanied by three adults). Boas spotted a black rhino just before we joined him, even though we did not actively track rhinos.

A trip like this does not constitute a game count, but it is an indication of what tourists are likely to see on a Kunene Region expedition. “If we get another year or two of good or even average rains, we could recover our wildlife to near pre-drought levels,” says Boas. “We will need to look at strategically translocating some species into areas where they are currently depleted, but the most important thing we can do right now is to support the game guards and their conservancies.”

The wildlife in Kunene can rebound, provided that the conservancies keep functioning and everyone working in the region pulls in the same direction. Tourists visiting Kunene discover how communities are conserving this harsh, yet spectacular part of the planet – and in doing so are supporting their important work.

Further reading

- Namibia is a spectacular wilderness destination. Read more here

- Read more about Namibia’s desert lions

- Western Namibia is a land of heat, sand, sea and remarkable biodiversity surviving against the backdrop of harsh but stunning scenery. Learn more about the land of ochre here

- Capture the most photogenic landscapes of Namibia – from Sossusvlei to Fish River Canyon – with this essential guide for nature photographers

About Gail Thomson

About Gail Thomson

Gail is a conservation scientist who focuses on carnivore conservation and human-wildlife conflict.

She has a passion for creating public awareness of conservation through her popular writings. She has many years of field experience in Namibia , Botswana and South Africa working on human-carnivore conflict and wildlife monitoring projects.

* With thanks to Conservancy Safaris Namibia and Jamma Communities & Conservation for supporting this trip.

What started as a stressful discovery evolved into one of my best wild dog sightings ever.

What started as a stressful discovery evolved into one of my best wild dog sightings ever.

Dr Paul Funston is a leading African conservationist with over 30 years of experience dedicated to the protection of lions. He holds a PhD in Zoology from the University of Pretoria, where he studied lion population dynamics and behaviour in Kruger National Park. Paul is a recognised authority on predator-prey relationships, habitat connectivity, and sustainable lion conservation.

Dr Paul Funston is a leading African conservationist with over 30 years of experience dedicated to the protection of lions. He holds a PhD in Zoology from the University of Pretoria, where he studied lion population dynamics and behaviour in Kruger National Park. Paul is a recognised authority on predator-prey relationships, habitat connectivity, and sustainable lion conservation.

Blondie, a well-known, collared pride male lion in Zimbabwe’s Hwange area, has been trophy hunted after being lured into a hunting area with bait – leaving behind 10 cubs

Blondie, a well-known, collared pride male lion in Zimbabwe’s Hwange area, has been trophy hunted after being lured into a hunting area with bait – leaving behind 10 cubs

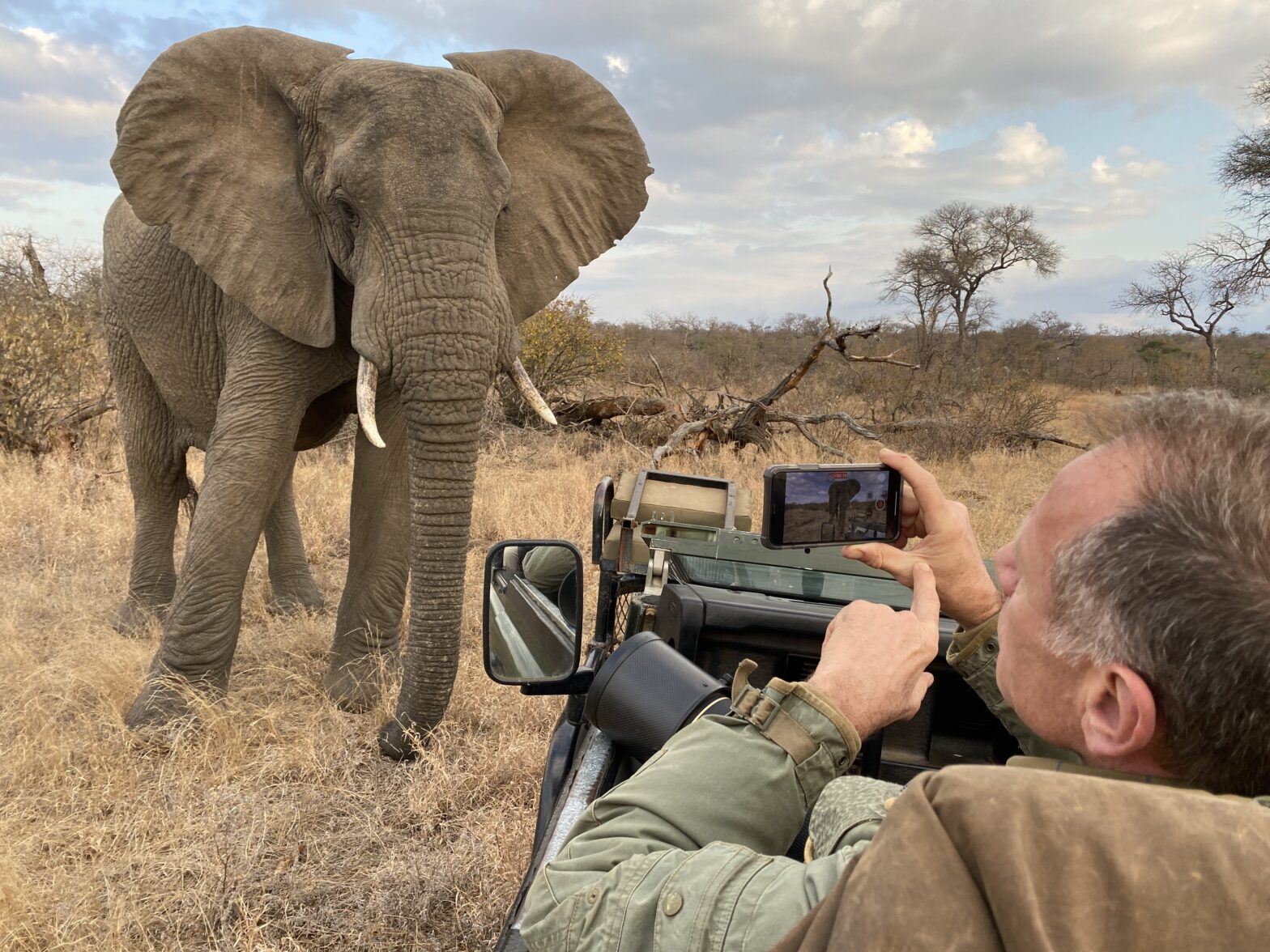

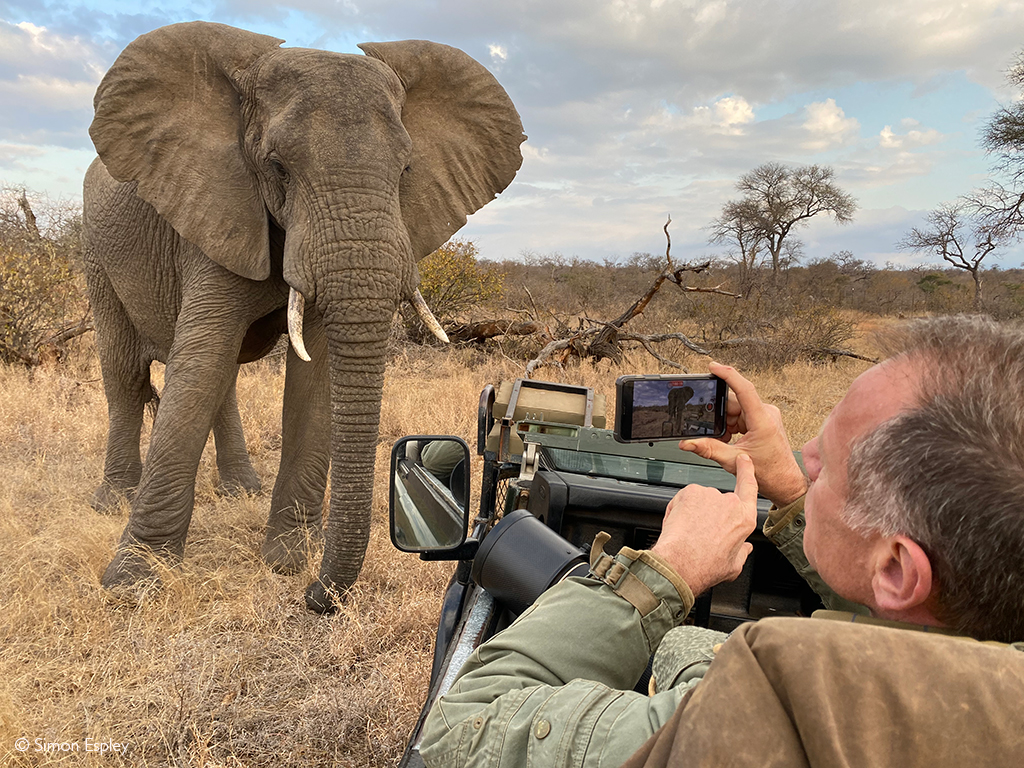

As social media rewards spectacle over substance, some private guides are prioritising viral content at the expense of ethics, safety, and the very animals they claim to champion. Drawing on firsthand accounts from across Africa and India, Adam Bannister explores the troubling rise of performative guiding – and makes a compelling call for a return to integrity, collaboration, and true connection with the wild

As social media rewards spectacle over substance, some private guides are prioritising viral content at the expense of ethics, safety, and the very animals they claim to champion. Drawing on firsthand accounts from across Africa and India, Adam Bannister explores the troubling rise of performative guiding – and makes a compelling call for a return to integrity, collaboration, and true connection with the wild

Adam Bannister is a South African-trained biologist, safari guide, author and storyteller who has spent nearly two decades immersed in some of the world’s most iconic wild places, from the Sabi Sands and Maasai Mara to the deserts of Rajasthan and the forests of Rwanda and Peru. With a passion for training guides,

Adam Bannister is a South African-trained biologist, safari guide, author and storyteller who has spent nearly two decades immersed in some of the world’s most iconic wild places, from the Sabi Sands and Maasai Mara to the deserts of Rajasthan and the forests of Rwanda and Peru. With a passion for training guides,

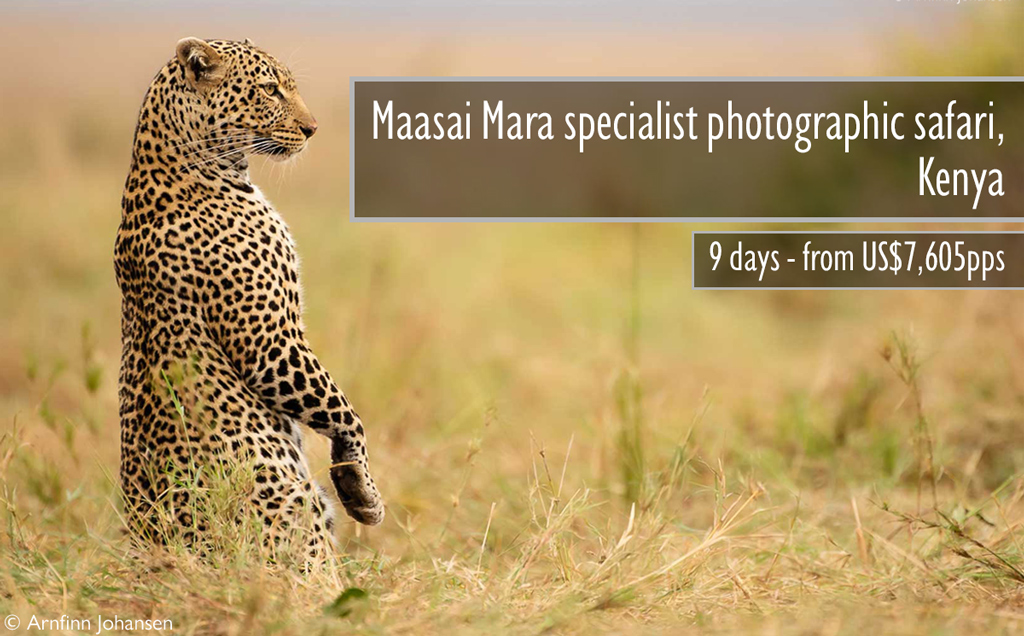

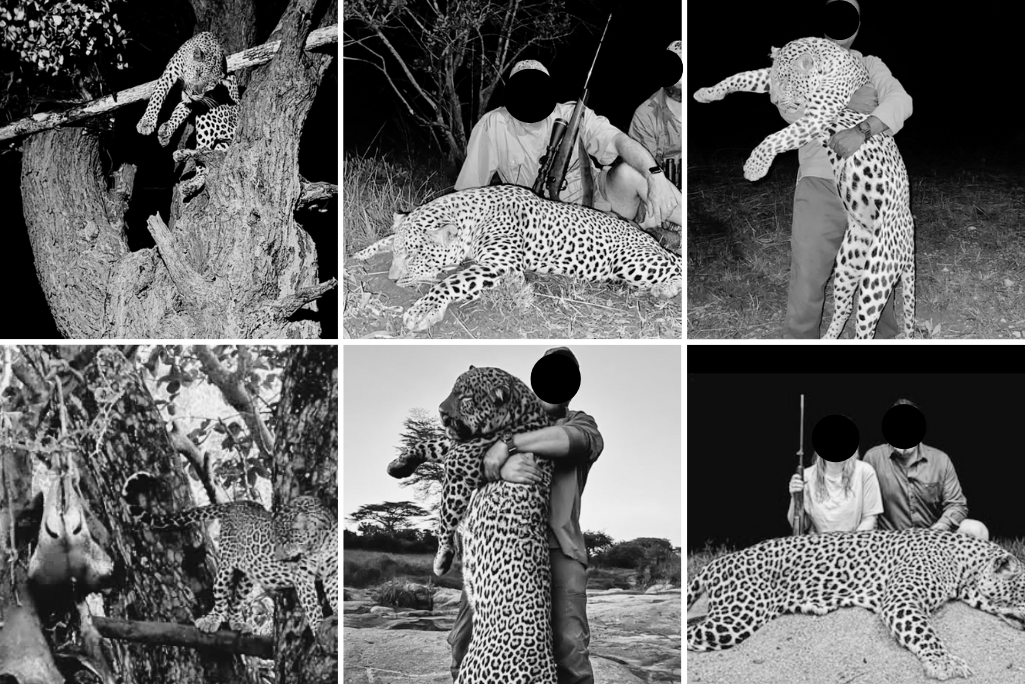

Leopards are Africa’s most enigmatic big cats: silent, solitary, and vanishing fast. Behind their fading presence lies a thriving global industry built on prestige, profit, and skull measurements. According to a

Leopards are Africa’s most enigmatic big cats: silent, solitary, and vanishing fast. Behind their fading presence lies a thriving global industry built on prestige, profit, and skull measurements. According to a

Born in Kassel, Germany, Christina is a clinical psychologist. In her spare time, she explores wild corners of Africa with a camera in hand. Her travels have taken her to South Africa, Kenya, Botswana, Namibia, Tanzania and Uganda. Wildlife photography is her mindfulness – a meditative exercise in patience, observation, and reverence for the natural world.

Born in Kassel, Germany, Christina is a clinical psychologist. In her spare time, she explores wild corners of Africa with a camera in hand. Her travels have taken her to South Africa, Kenya, Botswana, Namibia, Tanzania and Uganda. Wildlife photography is her mindfulness – a meditative exercise in patience, observation, and reverence for the natural world.

A professional wildlife photographer and guide from Johannesburg, Ernest’s passion for wildlife began during childhood visits to Kruger. Fresh out of high school in 2010, he sacrificed three electric guitars and an amplifier for his first starter-bundle camera. Thereafter, he spent years honing his skills at Walter Sisulu Botanical Gardens, photographing the resident Verraux’s “eagles.”

A professional wildlife photographer and guide from Johannesburg, Ernest’s passion for wildlife began during childhood visits to Kruger. Fresh out of high school in 2010, he sacrificed three electric guitars and an amplifier for his first starter-bundle camera. Thereafter, he spent years honing his skills at Walter Sisulu Botanical Gardens, photographing the resident Verraux’s “eagles.”

Based in San Diego, California, Mary’s roots in theatrical design and visual storytelling give her wildlife photography a narrative depth. Mary has photographed wildlife across the globe, from Africa’s golden plains to the icy stillness of the Arctic. But it’s the quiet moments – glances, gestures, pauses – that captivate her. Mary’s work honours the untamed and tells stories of connection. When not in the field, she’s home editing photos with coffee and a cat by her side.

Based in San Diego, California, Mary’s roots in theatrical design and visual storytelling give her wildlife photography a narrative depth. Mary has photographed wildlife across the globe, from Africa’s golden plains to the icy stillness of the Arctic. But it’s the quiet moments – glances, gestures, pauses – that captivate her. Mary’s work honours the untamed and tells stories of connection. When not in the field, she’s home editing photos with coffee and a cat by her side.