Uganda's most popular tourism destination

![]()

Queen Elizabeth National Park offers a classic safari with a few twists. The impressive variety of habitats includes acacia woodland, grass savannah, lakes, rivers, dense papyrus swamps, rainforest and extinct volcanic crater cones with lakes.

For some 3 million years, the impassive Rwenzori Mountains have born witness to the natural and human forces that have shaped equatorial Africa. Following the line of the Albertine Rift, the western branch of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, these jagged, snow-capped peaks are evidence of a time when enormous tectonic forces shaped the face of the African continent. One day, these mountains will mark the line where the African continent will split in two, the ocean rushing in to fill the space. But only in the next 10 million or so years.

For now, the Rwenzori Mountains, or the Mountains of the Moon, serve as the dramatic boundary between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda and create the perfect backdrop for a unique and thriving wilderness.

The fantastic variety of scenery and safari experiences make it easy to understand why Queen Elizabeth National Park (QENP) is one of Uganda’s most popular safari destinations.

The basics

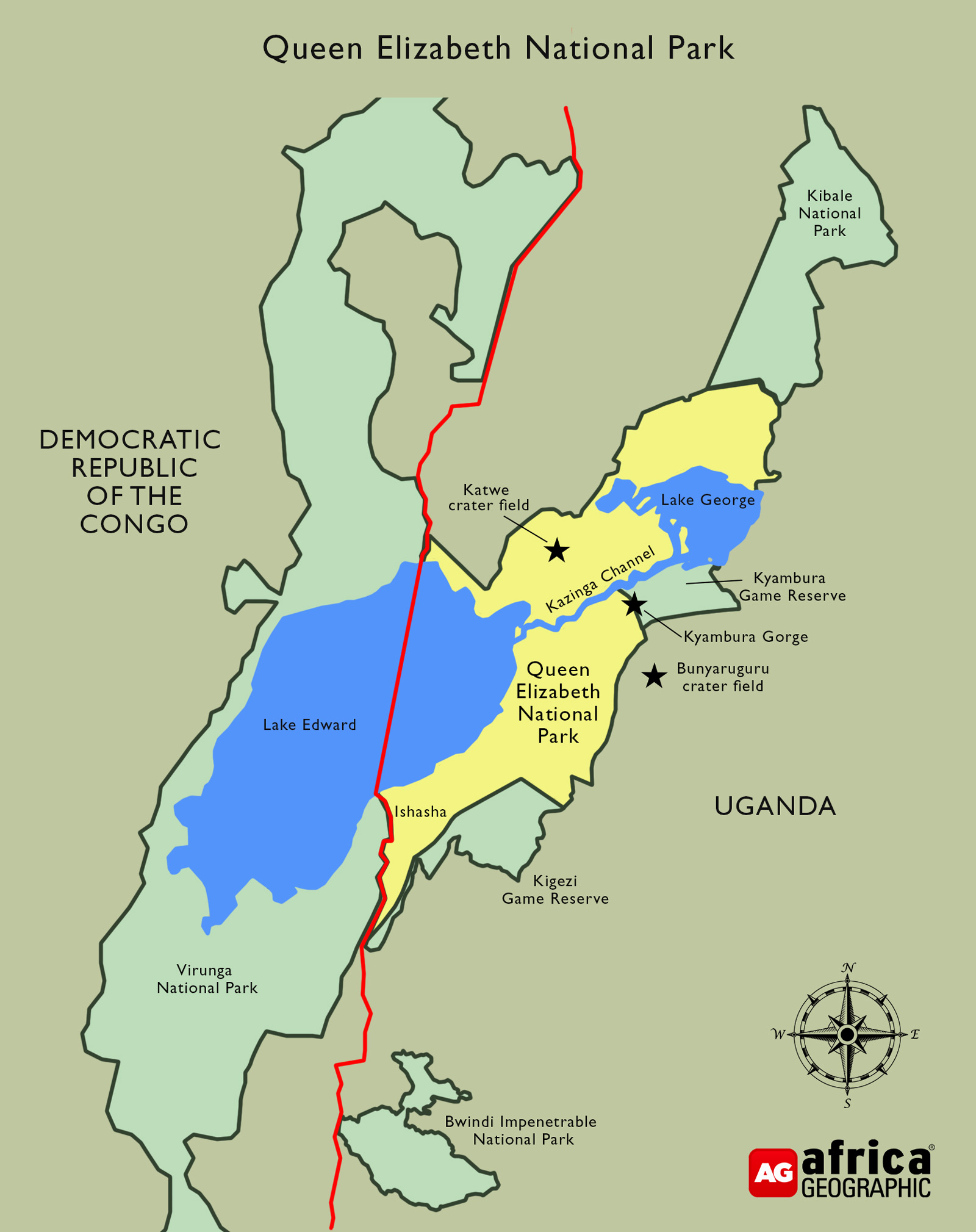

Situated in southwestern Uganda, QENP covers an estimated 1,978km2 (close to 200,000 hectares). The park is bookended by Lake George in the northeast and Lake Edward to the southwest, linked by a stretch of water known as the Kazinga Channel, and is contiguous with Virunga National Park in the DRC. The smaller Kibale National Park, Kigezi and Kyambura Game Reserves all border the park and serve as buffer zones for the ecosystem. Near the northern boundary of the park are four other major protected areas: Rwenzori Mountains National Park, Semliki National Park, Toro Game Reserve and Katonga Game Reserve. The gorilla-trekking Eden of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park lies about 150km to the south.

Formerly known as Kazinga National Park, QENP was renamed to commemorate a visit from Queen Elizabeth II in 1954, while Uganda was still under colonial rule. After independence and through the troubled decades that followed, the people of Uganda were to suffer terrible hardships and unimaginable cruelty, and, as is so often the case with human conflict, the wildlife paid a dreadful price as well. In so many ways, this is what makes QENPark such an extraordinary wilderness – it is a testament to the dedication of the local population’s determination to restore the country’s wildlife in the face of destruction wrought by war. This same dedication allowed Uganda’s elephant population to recover from 700 remaining individuals in the 1980s to more than 5,000 today – a revival of more than 600%.

Seismic scenery

To those who know and love Africa’s wild spaces, each one offers its own particular brand of unique beauty, and QENP is no exception. The land is pockmarked by explosion craters, magnificent calderas filled with either saltwater lakes or rich savannah, each capturing a feeling of a world within a world, a place where time seems to stand still. Seen from the air, it is easy to imagine the violent explosions of superheated gas that created the Katwe and Bunyaruguru crater fields.

A mosaic landscape of unique features and habitats, QENP’s fortunate visitors can go from exploring expansive savannahs dotted by euphorbia trees to the lush paths beneath the canopy of the Maramagambo Forest or drift down the Kazinga Channel on a boat, past one of the largest populations of hippos in Africa.

Tree-climbing lions

While the scenery is in itself a drawcard, QENP offers first-rate wildlife viewing as well, with over 95 recorded mammal species including elephants, buffalos, hyenas, leopards, lions, giant forest hogs and chimpanzees as well as herds of Ugandan cob. It is also one of the few places where visitors are almost guaranteed to see tree-climbing lions, found only in the southern Ishasha region.

Unlike their leopard cousins, lions are not typically particularly skilful tree climbers. Their impressive bulk puts them at the top of the predator hierarchy and imparts the power to pull down powerful prey, but they are not well designed for nimble balance or agile leaps. While all lions can and occasionally do climb trees, it is very seldom that they make a habit of it. Yet, in QENP, the lions are famed for their arboreal tendencies. Not even a shared familial ability to look comfortable whatever the situation can bely the incongruity of 150kgs of lion draped over the spikey limbs of a giant euphorbia tree. The most likely explanation for their behaviour is that it helps them to escape from the tsetse flies that plague the area and perhaps capitalize on the cool breezes a few meters above ground level.

The chimpanzees of Kyambura Gorge

In the mystical forests of Kyambura Gorge (cover image) in the heart of QENP ecosystem, there is a small, isolated population of primates that have become known as the “Lost Chimpanzees”. These chimpanzees are isolated from the other populations in the larger forested areas of the park, lone survivors cut off by the historic deforestation of the area. Now protected in the Kyambura Game Reserve which was created as a buffer zone to the national park, these chimps are the only habituated individuals in the region. While finding them is not always guaranteed (chimpanzees can cover vast distances in a short space of time), the experience of tracking them down is a reward in itself and contributes immensely towards the empowerment of the local community and the slow but steady process of reforesting key areas.

A birder’s paradise

It is no exaggeration to suggest that Queen Elizabeth National Park offers some of the best birding in Africa, thanks mainly to its astonishing variety of different habitats. There are over 610 different bird species recorded, the second-highest of any park on the continent. A visit to Lake Kikorongo (an extension of Lake George) offers the chance to see the legendary shoebills, though the keen birders can also occupy themselves with the search for the papyrus gonolek in the reeds while en-route. Raptors of every shape and size scud across the skies, from the vast martial and crowned eagles to palm-nut vultures and the angular outlines of keen-eyed grey kestrels. The lakes and channels provide the ideal habitat for a plethora of water and swamp species including both species of pelicans, white-winged and gull-billed terns, African skimmers, and swamp flycatchers. Moving from Ishasha to Mweya you will do well keeping an eye out for African crake, blue-throated roller, sooty chat, black-and-white shrike-flycatcher, northern black flycatcher, black-headed gonolek, moustached grass warbler, red-chested sunbird, and slender-billed weaver. Read more about bird-watching in QENP here Uganda’s other best bird-watching spots.

The safari experience

With so much to offer both in terms of scenic diversity and the variety of available activities, a visit to QENP should be savoured by allowing adequate time to explore. Booking a stay at one of several luxury lodges will guarantee access to an experienced and knowledgeable guide to tie together the richness of the biodiversity and history of the region, and, naturally, to make the most of the wildlife viewing opportunities. The lodge will also be able to tailor the various activities to the interests of its guests. There are also several budget accommodation options, and it is relatively simple for a competent driver to travel through most areas of the park and the surrounding regions. That said, be prepared for what is euphemistically referred to as an “African massage”, particularly just after the rainy season when the roads have dried out but are rutted and uneven where many a vehicle has fallen foul of the cloying mud during the wet months. The highest rainfall levels are experienced in April and May and October to November in the south, which can mean closed roads and postponed experiences. Though the drier months offer the best wildlife viewing, the park is open year-round.

Want to go on safari to Queen Elizabeth National Park? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()