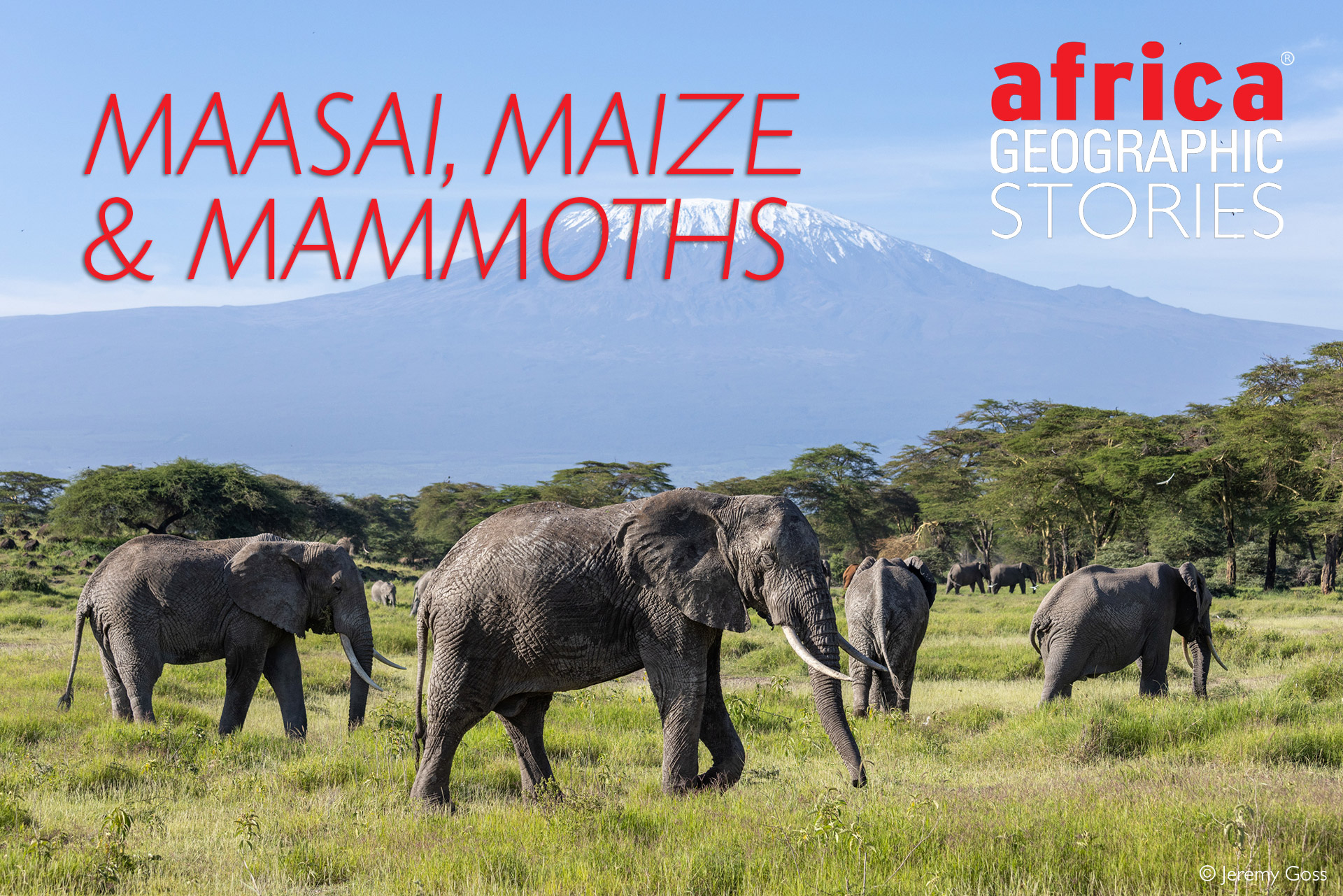

Human-elephant conflict in the Amboseli Ecosystem

The smoke clings to the corrugated iron ceiling like a cataract before slipping out of the open doorway and dissipating into the darkening sky. Night is approaching over the Kimana Sanctuary, a crucial elephant and wildlife corridor that links Amboseli National Park with the Chyulu Hills and Tsavo National Park in Kenya. The Big Life rangers stationed at Leopard Camp are relaxing in their kitchen hut after another long day of foot patrols, which help prevent human-elephant conflict in the Amboseli ecosystem.

The six of us sit on narrow benches while waiting for dinner. A smartphone plays YouTube videos of traditional Maasai songs as tinny lyrics accompany the trill of crickets outside. There is a jovial atmosphere because the World Cup is on tonight, and Parsitau and James are trading loud boasts in broken Swahili and English about how each country will fare.

It is Parsitau’s turn to cook a stew consisting of onions, tomatoes, sukuma wiki (kale), and nyama (meat, usually beef or goat). It’s what the rangers at Big Life eat most evenings, and is a firm favourite. He positions an aluminium plate on the table before flipping it over, and placing it upside down. Like a magician, he removes the blackened pot, unveiling its contents: a giant, steaming, white blob. The blob is known as ugali, a staple in Kenya, and is made by pounding maize meal in hot water until it becomes a thick, glutinous mass of carbohydrates. Before we start, Lekanayia goes around with a basin and a jug of water, and we take turns washing our hands. The ugali is then sliced like a cake and added to the stew. The rangers pick up small wads, making an indent with their thumb, before using it to scoop up the sauce. It is a hearty meal that is tasty and filling. We are going to need it.

Human-elephant conflict and agriculture

2022 was a challenging year for this ecosystem’s people and wildlife. The rains failed, and the entire region was crippled by drought. Bushmeat poaching has increased, cows have been reduced to walking skeletons, and livestock and wildlife carcasses are common. While all vegetation may have disappeared, groundwater from Kilimanjaro continues to resurface at the permanent swamps of Kimana, Namelok, Ilchalai, and at those inside Amboseli. These swamps are essential both to wildlife and the Maasai and their livestock, who retreat here in tough years. However, in the last thirty years, improvements to infrastructure and technology have opened this region up to the rest of the country. Many non-Maasai have realised the farming potential of the swamps’ fertile verges, and irrigated fields now line their perimeters. In addition, boreholes, some over 100m deep, have enabled people to transform dry patches of bushveld into electric green.

Maize is one of the most popular crops in Kenya as it fetches a high price at the market and, as the principal ingredient of ugali, is always in demand. Kimana’s permanent water and rich soils make for excellent growing conditions. However, cultivating maize here can come with a hefty cost because it’s not only farmers that look to reap its benefits. Maize also happens to be a favourite with elephants. Since the swamp shares an open boundary with the Kimana Sanctuary, there is little standing in the elephants’ way. This often leads to incidents of human-elephant conflict. In the weeks leading up to harvest, farmers must stay up, stay vigilant, and hope it is not their turn to be paid a visit by a peckish pachyderm.

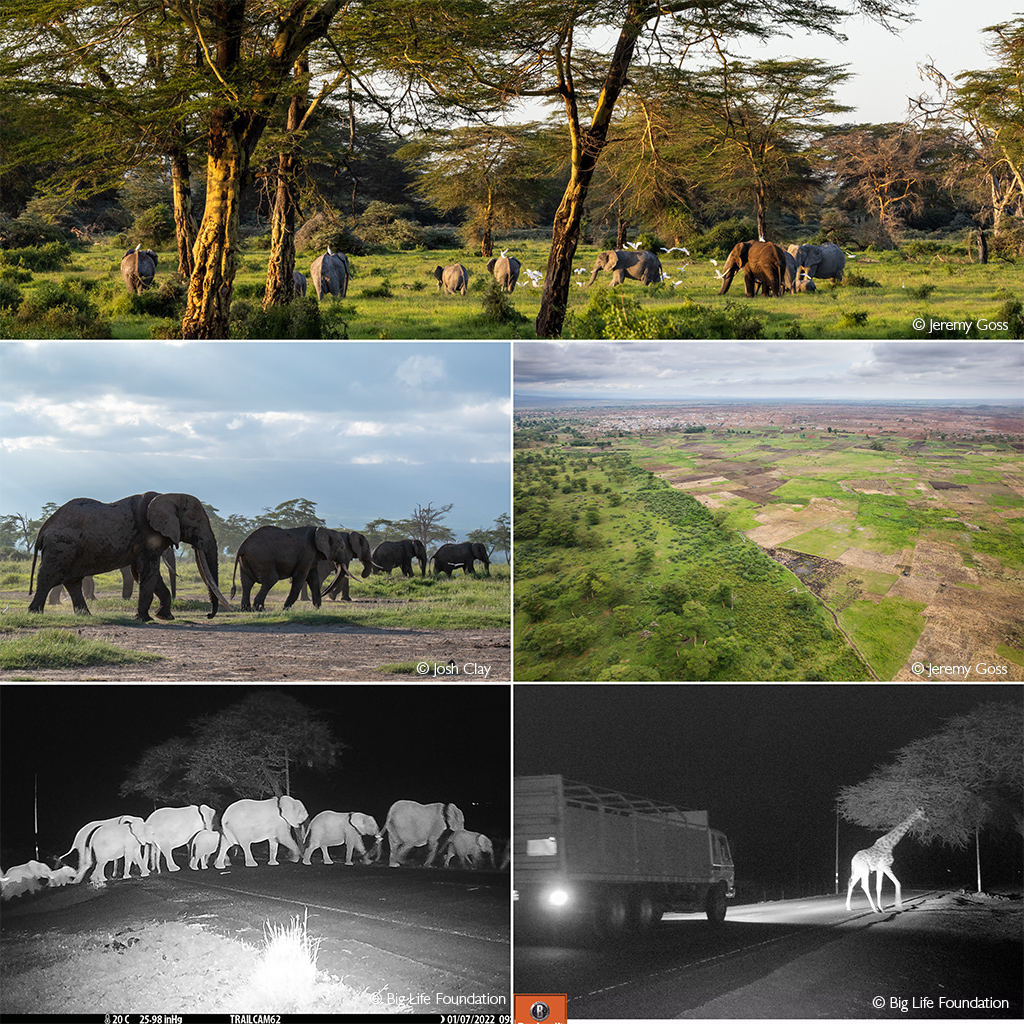

Renowned for their intelligence, elephants know better than to barge into cultivated areas at midday. The Big Life rangers who work to prevent these conflicts have told me they often see groups of males gathering near the edge of the Sanctuary at dusk, as if gathering to plan their tactics before heading into the fields after nightfall. Across Big Life’s area of operation, elephants have been responsible for 95% of the destruction caused by wildlife to farmland in 2022 (with wildlife-inflicted destruction totalling 30 hectares).

Protecting farmers and their crops

How can people with limited resources possibly deter the largest terrestrial mammal from eating its way through their livelihoods?

The trick is to get to the elephants before they enter the fields. Farmers shout, use torches, bang corrugated iron, and light small fires around the perimeters of their fields, which is often enough to stop them. But sometimes, the farmers need backup. This is where Big Life Foundation comes in. The organisation maintains close links with local communities, and most community members have mobile phones – and so, the Big Life Radio Room can be notified about potential elephant activity before the mammals get too close. Using Earth Ranger, a revolutionary conservation technology that shows the Radio Room where every single car and unit is in real time, Big Life can quickly deploy the ranger teams closest to the elephants. This dramatically improves the chances of preventing crop raids. Rangers are equipped with robust cars, powerful spotlights, and firecrackers. As a last resort, they can fire blanks from shotguns.

Back at the kitchen hut, kick-off for the upcoming World Cup game is imminent when the radio suddenly jolts into life and muffled Swahili filters through the room. It’s 10pm, and it’s time to move. Four elephants have been spotted on their way to some fields nearby, and a Land Cruiser is coming to pick us up. We feel every bump in the back of the Cruiser as it clatters to our destination, grinning as we avoid hitting our heads on its metal frame and laughing if someone miscalculates their dodge. It is challenging to retain a sense of direction as the sounds and sights of barking dogs, tuneless music, house lights, and passing vehicles blur into one. The town melts away, and we head towards a darker area punctuated by the small fires lit as elephant deterrents. Further on, torchlight shines into the sky, accompanied by raised voices. We are getting closer. Daudi parks the vehicle and stands on the roof to scan the fields with the spotlight. There is not much to see here, but shouting further on and a message from the radio confirm that the elephants are a few minutes away. A short drive soon reveals four large elephants moving steadily toward some maize fields.

Raid of the mammoths

If one compares the damage to crops by birds, insects, and rats to that of elephants, the elephants do far less damage. However, it is difficult to tell this to people when groups of six-ton jumbos regularly trample over their crops at 1am.

“Look! There’s Ganesh!” Daniel exclaims with a knowing smile. The Amboseli Trust for Elephants (ATE) has been monitoring this ecosystem’s elephant population for fifty years. According to their records, Ganesh, at the venerable age of 59, is currently the oldest elephant in the area. He is easily recognisable because of his single tusk and frayed ears. “Even though he is mzee (old), he still loves the excitement of crop raiding,” says Daniel.

We drive to within twenty metres of the elephants, our spotlight illuminating their massive frames. They change their course almost immediately – as if they know we have come to blow the whistle on their evening game. They hang around for five minutes, toeing the ground bashfully like guilty schoolkids, before heading towards the Sanctuary in their silent gait. I ask Daniel if they always behaved so well, and he replies, “Tonight was good because everything went without an issue. But sometimes, it can take until the next day to push them out of the fields, and they often run in the opposite direction, which causes more damage. Elephants are very destructive, but sometimes I feel like we are the ones in their way.”

As we rumble back to our base, Lekanayia is chattering excitedly – delighted that Senegal has won. I resist my wavering eyelids as I think back to what David said. The balance of life in this ecosystem is delicately poised and contains many uncertain elements each day. Seasons are more challenging to predict, and droughts like this one feel harsher than before. The human population and livestock populations are rapidly expanding. This is upping pressure on grazing, not just for livestock but also for wildlife. The famed nomadic pastoralist lifestyle of the Maasai has become all but sedentary as previous notions of land use have had to reckon with the more rigid rules of 21st-century property ownership. Humans in this region have always coexisted with wild animals, and communities shared vast open space. But now, these communities are subdividing rangelands to give each individual their share. Fences, small plots, and other arbitrary barriers are springing up, obstructing historic wildlife migration routes, entangling giraffes and antelope, and resulting in incidents like this evening’s, which are life-threatening to humans and animals.

Unhappy endings following human-elephant conflict

As Daniel said, these incidents don’t always have a happy ending, and one of the most distressing happened in early 2022. Rangers received a call that Tolstoy, the 51-year-old elephant with some of the largest tusks on the planet and one of Amboseli’s most treasured inhabitants, had suffered a severe spear wound to his ankle while raiding crops just outside of Big Life’s area of operation. He was treated and seemed to be doing well, but the spear had penetrated so deeply that it splintered some of the bone. The call that everyone dreaded came in April. Rangers from Kimana Sanctuary reported that Tolstoy was down and unable to get up. What followed was an exhausting day involving members of the Kenya Wildlife Service, Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, and Big Life Foundation to get Tolstoy back to his feet, but the combined efforts were not enough to save him.

Tolstoy’s death due to human-wildlife conflict was tragic, but such deaths are increasingly rare in this ecosystem. Across Big Life’s area of operation in 2021, they recorded zero human mortalities and only four elephant deaths resulting from conflict with humans. Out of a population of around 2,000 elephants. This population size is a remarkable figure on its own, as it marks the highest number of elephants in the Amboseli ecosystem since ATE started recording them 50 years ago.

Elephant numbers are on the rise across Kenya. While the country lost two more of its ‘super-tusker’ icons, Dida and Lugard, in 2022, both of these elephants died from natural causes – which would have been unheard of ten years ago during the peak of the poaching crisis.

Tolstoy and the other crop-raiding elephants do not mean to cause harm, and neither do the farmers trying to protect their livelihoods. Still, as more people settle in this area, interactions like this will become more frequent. This is the case throughout the country, and to prevent instances of human-elephant conflict from spiralling out of control, the work of organisations like Big Life Foundation, Tsavo Trust, the Mara Elephant Project, and the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust is critical for the long-term future of coexistence between people and elephants.

Hope for the future

Out of this recent land subdivision also comes opportunity. Big Life works with local people, community leaders, and regional and national governments to find solutions by creating wildlife corridors, maintaining rangelands, and protecting farmland to benefit this ecosystem’s iconic wildlife and people. The organisation has already begun leasing land parcels in strategic areas to ensure the connectivity of wildlife migration routes. They have also constructed over 100km of electric fencing around most of the region’s major farming areas, significantly reducing crop-raiding incidents. The fence comprises crucial wildlife corridors, such as the corridor connecting Amboseli National Park with the Kimana Sanctuary. While the corridor is less than 80m wide at its narrowest point, camera trap footage has shown it to be a great success, used by a diversity of wildlife – from springhares and aardvarks to giraffes and elephants.

The future of this landscape is by no means certain. But due to the unwavering dedication of over 350 rangers like those in Kimana Sanctuary, Big Life Foundation has helped maintain the fragile balance of this ecosystem. While there will be many more nights where elephants find themselves in cultivated areas, as long as Big Life receives funding and support, its rangers will also guide them to safety.

Resources

Lend your support and read more about Big Life Foundation here.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()