If you have ever been on a road trip through Botswana or Namibia, you would likely have encountered a veterinary fence. A checkpoint comes into view at a seemingly random location along your route. When you stop, you are asked if you have any meat and told to walk through murky water. If you were carrying some meat for your next braai or barbeque, this is the last you will see of it. Each vet fence comprises two parallel fence lines that extend for thousands of kilometres. Veterinary fences were not erected to inconvenience tourists, but why is this necessary? The answer is complicated and not without controversy in both Namibia and Botswana. Gail Thomson asks if Namibia and Botswana should bring down their veterinary fences.

Botswana’s fences have caused the deaths of millions of animals, while Namibians living north of its fence see it as part of the legacy of apartheid. Despite the social and ecological ruptures they have caused, the fences remain. As you will soon discover, taking down these veterinary fences is about much more than dismantling thousands of kilometres of wire and wooden poles.

Why veterinary fences? A historical perspective

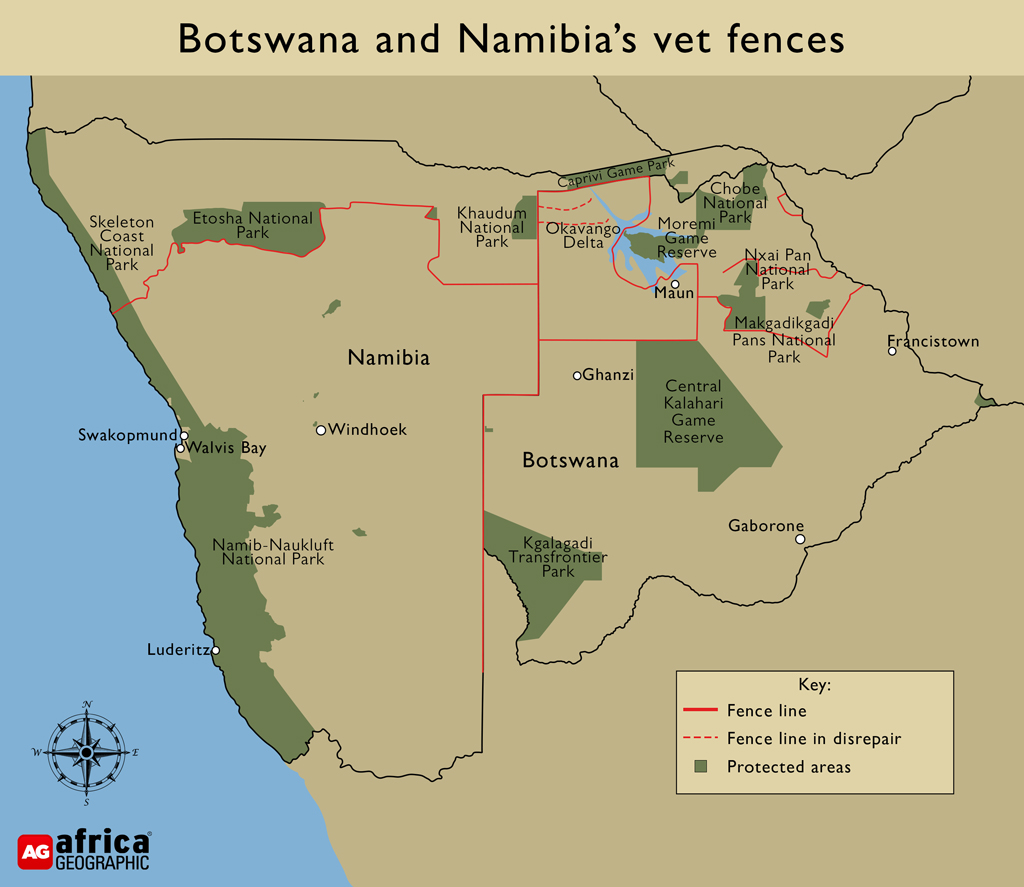

The Namibian fence is officially known as Veterinary Cordon Fence and unofficially as “the Red Line”, which is how it is depicted on maps. This 1,250km double fence line runs from the eastern border with Botswana, along the southern boundary of Etosha National Park and right through to the desert in the west.

The Red Line was initially developed as a concept rather than a physical fence as part of the German colonial government’s response to rinderpest in 1898. Starting in East Africa, rinderpest was a deadly disease introduced by cattle brought onto the African continent that wiped out over 90% of the cattle, buffalo and other antelope populations at the time. It also had a devastating effect on human populations due to the resulting starvation.

A series of police posts on the main roads were set up to prevent the movement of livestock from northern Namibia to southern Namibia along a line running east to west. Ultimately, these efforts were futile as rinderpest swept southwards through transmission between wild and domestic animals.

Despite its failure to control disease transmission, the Red Line was a useful political tool because it separated the southern part of Namibia that the Germans focused on colonising from the northern lands where they had less control. The area south of the fence became known as the Police Zone, i.e. the zone where colonising farmers could be ‘kept safe’ by the police.

When the South African government took charge of Namibia after World War I, they recognised the utility of the Red Line for political purposes and disease prevention. However, it was many years before a fence materialised from the concept. Instead, the Red Line was a 30–100km wide zone that was assumed to be free of livestock and most antelope due to a lack of natural surface water. The zone included the vast Etosha Pan and (at the time) its waterless surrounds. Strategically located police posts were used to prevent people from driving their livestock through the zone to access markets in the south.

An outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) in the 1960s finally created the impetus to turn the zone into a double fence line. Buffalo are primary carriers of FMD, which can be transmitted to cattle when they come into contact with each other. FMD can infect other antelope species (e.g. kudu) but these rarely transmit it to other species. Infected buffalo show few or no clinical signs of the disease, while cattle suffer from lesions in the mouth and feet that reduce their productivity (it is usually non-fatal for adult cattle).

The fence line and associated police posts further restricted human movement from north to south, which fitted well with the apartheid government’s intentions to keep the ‘black homelands’ in the north separate from ‘white farmlands’.

Botswana’s history as a British Protectorate rather than a colony means that its fences do not have the same colonial undertones. However, the whole purpose of their veterinary fences is to satisfy the European Union (EU) by controlling globally recognised transboundary animal diseases that could threaten European cattle farms. Most of these fences were erected after Botswana’s independence in 1966 and are far more extensive than Namibia’s Red Line.

The first fence to be erected (completed in 1958) was the Kuke fence running from the Namibian border, along the northern boundary of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR), then turning 90 degrees north towards the Okavango Delta. The Southern Buffalo Fence rings the Okavango Delta and meets the northern part of the Kuke fence. It was erected in 1982 to keep buffalo in the Delta and away from cattle farms, mainly to prevent FMD transmission.

The outbreak of Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia (CBPP), another recognised transboundary animal disease (infecting cattle but not African buffalo), prompted the construction of several more veterinary fences in the northern half of the country in 1995–1996. Due to the contagious nature of CBPP and its international trade significance, all cattle were slaughtered in Ngamiland (north-west Botswana) between 1995 and 1998. Two fences constructed at the time (the Setata and Nxai Pan fences) have since been removed. Altogether, Botswana’s many separate fences cover over 10,000 km.

Negative impacts of veterinary fences

While fences in Namibia caused some ecological disruption (hundreds of buffalo were shot south of the fence to prevent them from dying against the fence), the impact on Botswana’s wildlife was devastating. Millions of wildebeest and zebra died along the Kuke vet fence because it was inadvertently erected across their historical migration routes between the Kalahari and the Okavango Delta.

Besides the internal veterinary fences, the national boundary fences running between Namibia and Botswana cause severe disruption of wildlife movement in this central part of the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA). The initial construction of these fences coincided with significant declines in buffalo, tsessebe, roan and sable antelope in Namibia. Recent evidence from satellite collars on elephants reveals that family herd movements are restricted by fences, even though elephants frequently break the national boundary and vet fences.

The impacts of vet fences in Namibia and Botswana have been both socio-economic and ecological. In both countries, farmers living on the ‘wrong side’ of the fence (i.e. where FMD and other diseases are considered endemic) have access to few markets for their meat. Although many of these farmers keep cattle for cultural purposes and rarely sell their cows, limited market access makes a shift towards more commercial farming practices even less likely.

The continued strict separation between buffalo and cattle creates an economic and conservation problem. As a game species, disease-free buffalo are highly valued and sold in neighbouring South Africa for high prices. Still, game farms in Namibia and Botswana are prevented from stocking buffalo for fear of disease transmission. This limits the potential for the wildlife economy in both countries to outcompete the livestock farming industry and prevents buffalo from recovering its historical range.

Finally, maintaining thousands of kilometres of double fences is a significant cost for both countries, although probably more so for Botswana. Elephants are constantly breaking the vet fences, allowing cattle to enter wildlife areas (e.g. the Okavango Delta) and mingle with buffalo. If these cattle are herded back out again, they could cause disease outbreaks affecting all livestock farmers in the country.

The symbolism of the Namibian Red Line as a means of oppression and separation cannot be ignored, although a detailed discussion of this is beyond the scope of this article.

Veterinary fences are bad, but…

Wildlife-proof fences can reduce human-wildlife conflict, whether erected for disease control or some other purpose. Fence breaks between Etosha National Park, the Okavango Delta and their surrounding farmlands often result in livestock or crop losses and subsequent killing of the wild animals involved.

One doesn’t need a crystal ball to predict what would happen if these fences were removed entirely. Cattle herders searching for better grazing in these protected areas would push further into them, where lions and other large carnivores would easily pick them off. Conversely, lions and other carnivores would expand their range into the adjacent farmlands and cause even more conflict than currently.

Finding other ways of reducing disease transmission that do not include fences could open up international markets for meat and start to commercialise cattle farming. While this could have positive implications regarding poverty alleviation, it may also intensify human-wildlife conflict by increasing the economic value of lost livestock. Both countries already struggle to provide sufficient payments for livestock losses due to human-wildlife conflict, even in places where livestock are not farmed commercially.

Finally, veterinary protocols in both countries that are associated with vet fences – e.g. livestock inspections and ear tags for tracing cattle ownership – maintain relatively high standards of disease control. If vet fences come down, such protocols could be relaxed or disregarded, leading to more disease outbreaks among livestock.

Looking to the future

If the negative impacts of vet fences generally outweigh the positives, why do these two independent African nations still maintain them? The short answer: to maintain access to the lucrative EU market for meat products.

The highest value market for livestock from both countries is the EU. If infected meat is imported into the EU, it is possible (though far from as likely as live animal imports) that FMD and other cattle diseases will infect European cattle. Consequently, if meat-exporting countries such as Namibia and Botswana cannot prove to the EU that their meat is not contaminated, they will be locked out of this lucrative market.

Therefore, solutions to the vet fence problem focus on reducing the likelihood of disease transmission to the point where it can be proven that meat from infected zones poses no threat to international markets. The first step in this direction is using an animal management system called Commodity-Based Trading (CBT) that combines livestock management, quarantine zones, and specific ways of slaughtering at abattoirs to reduce the chances of disease transmission to near zero.

This system is recognised by the international governing body World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly OIE) which maintains standards for animal imports and exports to reduce the chances of disease transmission. However, the EU imposes stricter standards than those recommended by WOAH and thus is unlikely to accept meat produced through CBT methods.

A sudden increase in the supply of relatively cheap meat from Africa is seen as a threat to farmers within the EU, so this discussion goes beyond disease transmission and into the realm of politics. Until that changes, farmers may have to settle for using CBT to access markets within Africa and others outside of the EU, which are at least stronger than domestic markets in those zones.

The need for more intensive livestock management to implement CBT has a silver lining. If cattle must be herded and kept away from buffalo and other wildlife as much as possible (as per CBT guidelines), they will be better protected from predators. Better-managed cattle are also more productive, as young animals can be treated timeously when the herder notices they are ill. The Herding 4 Health programme in Botswana uses this approach to improve livestock health, open access to regional African markets, and reduce cattle losses to lions and other predators.

Bringing the fences down

Vet fences have been a constant presence in Botswana and Namibia for decades. The reasons for erecting and maintaining these fences go far beyond disease transmission. This means that any efforts to take these fences down must include, but not be limited to, technical fixes related to animal health. Political interventions, trade deals, and changing farmer and veterinary perceptions are essential. One must also consider the unintended negative consequences of taking fences down and have strategies in place to mitigate these wherever possible.

If Botswana and Namibia can navigate these uncharted waters successfully, bringing selected fences down could herald a new era for improving livelihoods, restoring wildlife migratory routes and further integrating the livestock and wildlife economy. Are these potential long-term benefits worth the extra effort and economic uncertainties? If so, we should seriously consider bringing at least some of the fences down.

Gail Thomson would like to thank Dr Mark Jago (Namibia) and Dr Mark Bing (Botswana) for their input into this article based on their veterinary expertise.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()