The wolves of the mountains

High upon the Afroalpine plains of Ethiopia’s Bale Mountains, a big-headed African mole-rat raises its head cautiously out of its tunnel. Showing off an impressive pair of incisors, it glares myopically at the surroundings from beneath a deep-set brow before venturing forth from its bolt hole to feed. The mole-rat has good reason to be so vigilant – it occupies one of the last bastions of Africa’s most endangered and intriguing carnivores: the Ethiopian wolf. And they are expert rodent killers.

The Ethiopian wolf

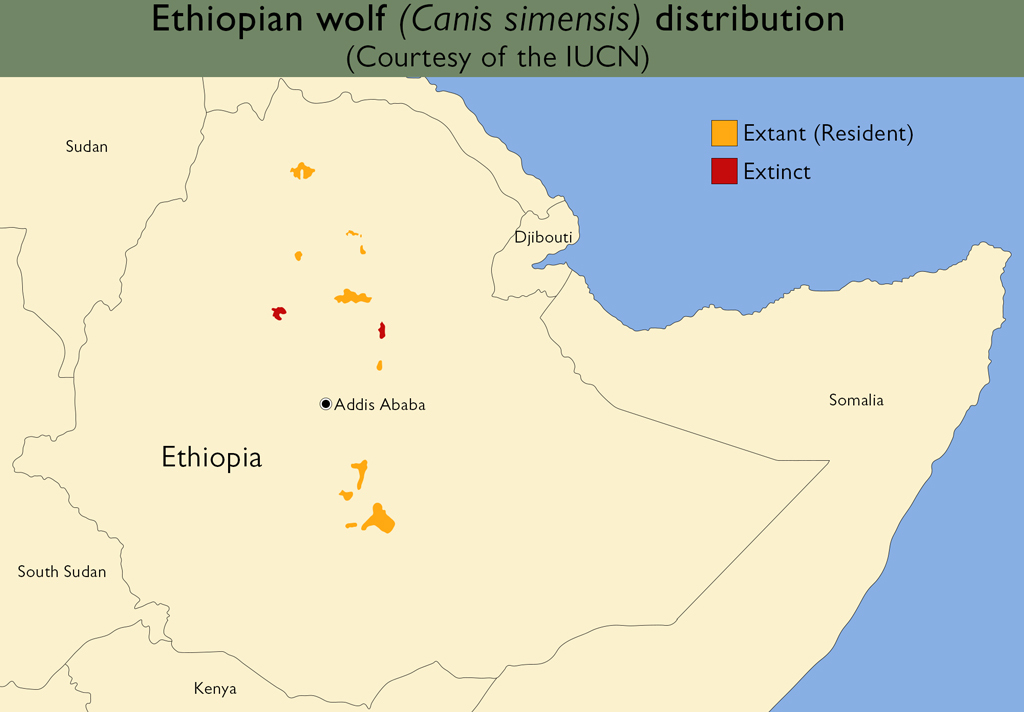

Ethiopian wolves (Canis simensis) are handsome, russet-coated canids found only at altitudes above 3,200 metres in the Highlands of Ethiopia. As unusually specialised predators, they have the lamentable honour of being the most endangered carnivore in Africa and the rarest canid species worldwide. Given their particular habitat preferences, it is unlikely that Ethiopian wolves ever occurred at high numbers or densities, but due to anthropogenic pressure, their populations are now highly fragmented. Today, Ethiopian wolves are restricted to a handful of isolated mountain enclaves, threatened by encroachment and disease. This understandably dominates most of the available commentary on these unique animals.

One regrettable consequence of their conservation plight is that the more nuanced aspects of their evolutionary history and fascinating ethology are often overlooked. Yet, the Ethiopian wolf is a marvel in its own right – a creature closely related to Eurasia and North America’s more familiar grey wolves but with a distinctly African twist. Millions of years ago, as canid ancestors trotted in from Asia and Europe to the welcoming lands of Africa, some of them gravitated to a less hospitable realm. Largely freed from competition with rival predators, the ancestors of the Ethiopian wolves found themselves in rodent heaven on the “roof of Africa”.

The cursorial hunting techniques so popular with many large canid species (like grey wolves or the African wild dog) are of little use on the sparse Afroalpine plains. Thus, Ethiopian wolves adopt a more patient, almost feline approach to hunting. They stalk through the heath and grasslands, using keen hearing to pinpoint rodent burrows. When a suitable target is identified, the wolf will wait for the rodent to emerge before leaping into the air and descending serval-like from above. By necessity, this hunting style is a one-wolf job, and Ethiopian wolves are predominantly solitary hunters (though interestingly, they often hunt within large herds of foraging geladas). However, there are rare instances when packs band together to hunt larger prey like the calves of mountain nyala.

Quick facts

| Height: | 53-62cm |

| Mass: | Males: 14.2-19.3kg |

| Females: 11.2-14.1kg | |

| Social structure: | Packs |

| Gestation: | 60-62 days |

| Conservation status: | Endangered (formally Critically Endangered) |

Wolf, jackal, or fox?

Like the African wild dog (painted wolf), the Ethiopian wolf has several alternative (and potentially confusing) monikers. They are sometimes referred to as Simien foxes, Simien or Ethiopian jackals, Abyssinian wolves and even a horse’s jackal (a local name supposedly in reference to their habit of consuming the expelled placentas of post-parturient horses and cows).

In terms of size and shape, Ethiopian wolves are not dissimilar to coyotes, though lankier and with longer muzzles. Their ambush-based hunting habits resemble smaller canid species like jackals, while their social structures are unequivocally wolf-like. And finally, their ochre-hued coats are positively vulpine.

Perhaps this foxy colouring led Oscar Neumann, a German naturalist of the early 20th century, to describe the Ethiopian wolf as “only an exaggerated fox,” but Oscar was to be proven mistaken. We now know that the Ethiopian wolf’s closest African relative is the African wolf (Canis lupaster), an animal which, until 2015, was thought to be a golden jackal. What’s more, the ancestor of the African wolf was a genetically admixed canid of 72% grey wolf (Canis lupus) and 28% Ethiopian wolf ancestry. To put it simply, as far as we know, the Ethiopian, African, and grey wolves, together with coyotes and golden jackals, all evolved from the same common ancestor. The Ethiopian wolf is the most basal member of that group, meaning that it diverged early on, about a million years before the rest. All species appear to be sufficiently closely related to hybridise and produce fertile offspring.

Wolf pack

Ethiopian wolves have pack structures similar to both grey wolves and African wild dogs. The family groups may number up to 20 individuals, though they are generally smaller, with an average of six pack members. These packs occupy territories (the size of which varies depending on rodent populations), and all individuals contribute to the defence of these territories through scent-marking, vocalisations and aggressive interactions.

A breeding pair monopolises the reproductive affairs of the pack, and the remaining females are reproductively suppressed. Furthermore, the breeding female will only accept the advances of her pack mate (or males from other groups if she happens to sneak away). The helpless pups are born into an underground den, and it will be three weeks before they emerge to peer out at their new, chilly world. Raising the next generation is a team undertaking, with all wolves helping protect and feed the pups (view a gallery featuring the antics of a young Ethiopian wolf pack here). Subordinate females may even lactate and help suckle larger litters.

At around two years of age, subordinate females tire of life under their mother’s reproductive tyranny and disperse in search of a new pack – either forming their own with a suitable dispersal male or integrating into an existing one.

Keeping the wolf from the door

Most available reading on Ethiopian wolves suggests their current range is limited to seven mountain populations. However, this is dated information, and the situation is likely worse than most realise. The last formal population assessment came in 2011 when the IUCN Canid Specialist Group suggested that they are now extinct in Mt. Gunda in South Gondar (one of the seven listed remaining ranges). Only a handful of wolves remained in the North and South Wollo Highlands at the last count in 2000. The Simien and Bale Mountains (sections of which are protected by eponymous national parks) are the last remaining population strongholds of Ethiopia’s wolves.

For the most part, direct persecution has not contributed enormously to the decline of the Ethiopian wolf, as they very seldom prey on livestock and thus do not represent an immediate threat to farmers. They are also well protected under Ethiopian law. It is habitat loss that has driven them to the verge of extinction. The wolves are designed to thrive at high altitudes in particular habitats, and over 60% of all land above 3,200 metres in Ethiopia is now farmland.

Worse still, with people comes disease in the form of canine distemper and rabies spread via domestic dogs. Many of Africa’s large carnivores (including lions, wild dogs and Ethiopian wolves) are incredibly susceptible to these highly fatal viruses, and they can spread like wildfire in social species. In the already tiny populations of Ethiopian wolves, the effects of an outbreak can be devastating to the point of local extinction. An additional challenge posed by domestic dogs is the ability of the two to interbreed, endangering the already dwindling genetics of the wolves.

The complexities of the threats facing Ethiopia’s wolves and the efforts to save them are dealt with in greater detail in a previous article, “Cry Wolf: What it Takes to Save Africa’s Most Endangered Carnivore”. Fortunately, nature is always resilient if given the chance, and the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme recently recorded 94 pups born during the 2021/2022 breeding season.

Final thoughts

As canids spread across the globe millions of years ago, their versatility and opportunistic natures proved a recipe for success. But the more specialised they became, the more vulnerable they were to the impact of humans. For the Ethiopian wolves, their niche requirements combined with the inexorable advance of people, farms and the associated dangers have been disastrous.

Fortunately, there are still places where the wolves are safe and thriving, and concerted conservation efforts have seen them reclassified from “Critically Endangered” to “Endangered” – one step closer to ensuring the future for Ethiopia’s exquisite and unique wolves. To book your African safari to see Ethiopian wolves in the wild, click here.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()