baobabs, fossas & rocks with teeth

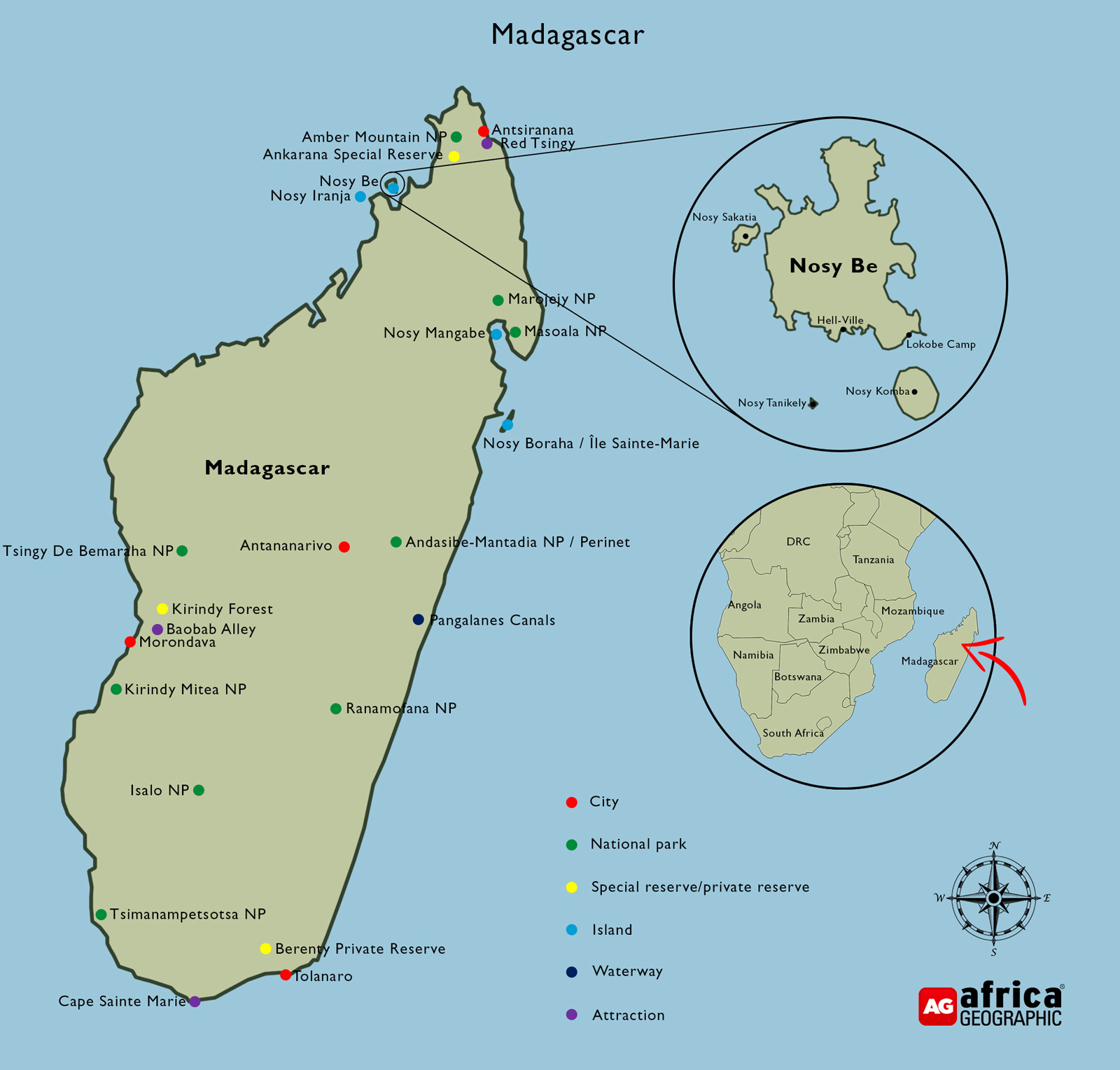

This time we adventure to western Madagascar, in our four-part series on this wondrous island. See the resources section at the end of this story for the other three stories in the series.

For the last 88 million years, life on Madagascar has been on its own – creating an island of evolutionary oddities and myriad diverse travel experiences. Sometimes referred to as a “Noah’s Ark” or the “eighth continent” due to its geographic isolation and high levels of endemism, the island of Madagascar is, simply put, enormous. It is approximately 587,000km2 (around two and a half times the size of the United Kingdom). A combination of ocean currents and dramatic topography has created a tapestry of different climates and habitats perfectly suited to the island’s peculiar inhabitants (or the other way round).

The island is home to over 300 recorded birds (60% of which are endemic) and 260 species of reptile – including two-thirds of the world’s chameleon species. There are over 110 species of lemurs spread throughout Madagascar’s protected areas, in a variety of shapes and sizes but all possessing a shared, wide-eyed charisma. Six of the world’s eight baobab species occur only in Madagascar. All in all, the natural history is unique, shaped by the fascinating and beautiful, isolated island habitats.

In an ideal world, a trip to Madagascar would extend over weeks to give the curious traveller every opportunity to explore the magnificent island. Realistically, however, time is usually limited and deciding where to invest one’s attention is guaranteed to create a significant traveller’s quandary. This four-part series is intended to help guide this decision.

Western Madagascar

The curvy outline of Madagascar’s western edge is a testament to a time when the island was still joined to Africa (then part of Gondwanaland) around 165 million years ago. The sheltered bays and coves closest to its parent continent were the island’s gateway to the outside world for the antecedents of its amazing wildlife. It is here that the flotsam carrying the earliest lemur ancestors would have washed ashore, while the first chameleons would have taken their initial wobbly steps into a new home on the beaches. Both of these creatures would find themselves with a world all to themselves and would go on to evolve into the myriad species known (and some still undiscovered) today.

The hot and dry region is well-deserving of its title of the ‘Wild West’, far removed from the country’s capital Antananarivo and the rich, lush forests of the east. Divided into a northern and southern section with little in the way of roads linking the two, getting to and around western Madagascar requires a degree of patience while travelling through farmlands and sparse savannas. This forbearance will, however, be richly rewarded by the scenery and wildlife on offer. Some of the most iconic images and scenes associated with Madagascar are from its enormous western portion. From upside-down trees to rocks with teeth, the island’s arid west is full of Madagascan specialities.

Allée des Baobabs – Baobab Alley

Of all of Madagascar’s evocative settings, it is perhaps Baobab Alley that receives the most photographic attention (see our cover photo above). This exquisite stretch of dusty red road is lined by towering baobabs, some of which are over 2,800 years old and around 30m in height. Against the short surrounding scrubland, these giant Grandidier’s baobabs (Adansonia grandidieri) stand out as what is now recognised as a natural monument. At sunrise and sunset, tourists flock to admire their dramatic shapes in the golden light – their long straight bodies and peculiar crowns (like roots planting themselves into the sky) create an entirely alien atmosphere.

Of the eight species of baobab in the world, six are found only in Madagascar. The Grandidier’s baobabs of Baobab Alley are the tallest. They were once part of Madagascar’s vast tracts of dry deciduous and tropical forests. Sadly, slash and burn agriculture and relentless human advancement are estimated to have destroyed around 50% of the island’s forests in the last 60 years, and these stately giants now stand in isolation.

After that sombre thought, visitors can travel just seven km from the Baobab Alley to appreciate an ancient story of boundless love in the form of two intertwined za baobabs (Adansonia za) – the ‘Baobab de Amoureux’. The legend goes that two people were once desperately in love but were already promised to others. Desperate, the couple appealed to their god, and thus the baobabs came to be – entangled for eternity.

Kirindy Mitea National Park

Not to be confused with Kirindy Private Reserve further north, the 722km2 (72,200 hectare) Kirindy-Mitea National Park is one of the more remote national parks, situated on the west coast, south of the sleepy beach town of Morondava. The large park encompasses the overlap of southern and western biotypes. The habitats are many and varied, including dry deciduous forest, tropical dry forest, spiny forest, mangroves, beaches and coral reefs. An added advantage is that few tourists travel here because it is so remote, and one can explore the hiking trails in relative seclusion (with a mandatory guide, of course).

Kirindy Private Reserve

The relatively newly established Kirindy Private Reserve (Kirindy Forest) is situated north of Morondava and is privately owned and run. Despite the region’s destructive history of logging, wildlife here managed to survive and is now flourishing. This is a reserve and not a national park, meaning that night walks are available through the reserve itself, rather than just on the outskirts. (Night walks in the national parks of Madagascar have been banned, but guides are still permitted to lead groups of tourists along the roads bordering the parks to look for nocturnal lemurs, chameleons, and other creatures of the Madagascan night.)

Kirindy Forest is the best place in Madagascar to see the lithe, carnivorous fossa – the island’s largest mammalian predator. Looking something like a cross between a cat and a mongoose (though more closely related to the latter), the acrobatic fossa is equally at home in the trees or on the ground while hunting for reptiles, birds, and lemurs. Fossa start their mating season in November, when the females take to the trees, call loudly and wait patiently to take their pick of appropriate suitors. A visit during this time does not necessarily guarantee a fossa sighting but does increase the likelihood of a genuinely exceptional sighting of one of the island’s most exciting animals. Though fossa have a widespread distribution across the island, they occur at extremely low densities and are seldom spotted in the other protected areas.

In addition to the fossa, Kirindy Forest is also home to the smallest lemur on Earth: the critically endangered Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur. This minuscule primate weighs just 30 grams on average. It is named after Madagascan primatologist and conservationist Berthe Rakotosamimanana (the reason for selecting her first name can be left to the imagination.) These tiny creatures wrap themselves in vines and sleep during the day, emerging at night to forage, so a night exploration is essential. This is especially true because they are creatures living on the edge of existence – experts suggest that they could be extinct in the next ten years if the current rate of deforestation continues.

Though the forest is bursting with reptile and birdlife, there is one final mammal species of Kirindy Forest deserving of a mention. The Malagasy giant rat (giant jumping rat) is a regular nighttime visitor to the camp and looks very similar to a springhare.

Tsingy De Bemaraha National Park

The term “tsingy” loosely translates as a place where you cannot walk barefoot – or to walk on tiptoe. It is the perfect description for the extraordinary geology of Tsingy de Bemaraha National Park. Together with the Tsingy de Bemaraha Strict Nature Reserve, the region is a UNESCO World Heritage Site centred around the ‘Great Tsingy’ and the ‘Little Tsingy’. In places, the jagged limestone pinnacles stretch almost as far as the eye can see – a sawtooth landscape shaped by the forces of water and wind over millennia.

The park’s infrastructure is well developed and maintained, but a certain degree of physical fitness is necessary to make the most of a trip. The weather is always relatively hot, and even though the park is only accessible during the cooler dry season (April to November), temperatures regularly exceed 35˚C on the plateaus. The hikes include travelling across via ferrata, walkways and suspension bridges before descending into narrow and humid caves and canyons.

Naturally, the park’s peculiar geography is inhabited by Madagascar’s usual array of weird plants and strange creatures adapted to exist in very narrow niches. These include bottle trees and orchids to the giant coua (a bird) and the extremely rare Madagascan big-headed turtle. Of course, lemurs are ever-present, and those hoping to complete their checklists (with over 110 lemur species on the island, this would be an impressive feat) could tick off the Von der Decken’s sifaka and red-fronted lemurs, among others.

The ins and outs of exploring western Madagascar

Timing a trip to western Madagascar requires some delicate balancing of weather, wildlife and wishes. Throughout the island, some of the wildlife species go into a state of torpor during the dry winter months, starting around May and continuing until November. This applies to everything from chameleons to lemurs and is particularly true in the drier sections of Madagascar, where plant and food availability are scarce. In the west, the parks come to life during the hot rainy season from November to March, but this is also when the roads are at their worst, and some areas are completely inaccessible. May offers a good compromise – the vegetation is still lush after the wet season, and the animals are still mostly active. However, those wishing to see baby lemurs should delay until September/October.

There are plenty of budget and camping opportunities in or near all of the major parks and some more exclusive options for the more discerning visitor. The prime western destinations are far from the capital and often require a long drive on rough roads or chartered flights. Once there, it is essential to try and plan hikes and activities for the early morning or late afternoon to avoid the worst of the heat. Plentiful water and sunscreen supplies are crucial, as is a hat. Acquainting oneself with the colourful lives and personalities of local people en route is an inevitable part of exploring western Madagascar and only adds to the richness of the experience.

Final thoughts

Madagascar is a fantastical land – a natural evolutionary playground and a human kaleidoscope of cultural influences. Remarkable, offbeat, and enticing, this magical island offers an intoxicating combination of unique wildlife viewing and magnificent scenery. There is far more to Madagascar than our series could ever hope to convey, but there is no question that it is a country with something to offer everyone. Our travel consultants are always on standby to help you plan the Madagascan holiday of your dreams.

Want to go on safari to Madagascar? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

Resources

Photographers:

Ken Behrens is a birder, naturalist, consultant, guide, and photographer, who is based in Madagascar. He is the co-author of several books, including Wildlife of Madagascar. His work can be seen at ken-behrens.com

Alistair Marsh’s photography can be seen and purchased from www.alastairmarsh.co.uk

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()