The Kruger National Park’s northern reaches offer arguably the most scenic, biodiverse, and historically fascinating experience of the Greater Kruger area. Consider that this slice of wildland is sandwiched between two great rivers, three countries and millennia of geological and social upheaval – and you begin to get the picture. This is the 24,000 ha Makuleke Contractual Park, previously known as the Pafuri Triangle.

Since the Early Stone Age, humans have been drawn to this land of legends, and their impact is there for all to see – from rock art and cave paintings to stone fortresses perched on hilltops and ancient baobab trees etched by passers-by. The deep canyons and riverine forests whisper with the tales of tribal skirmishes, explorers, poachers, gun-runners, slavers and great white hunters. Civilizations have come and gone and left their mark, and the current custodians – the Makuleke people – have committed the land to conservation.

TWO GREAT RIVERS MERGE

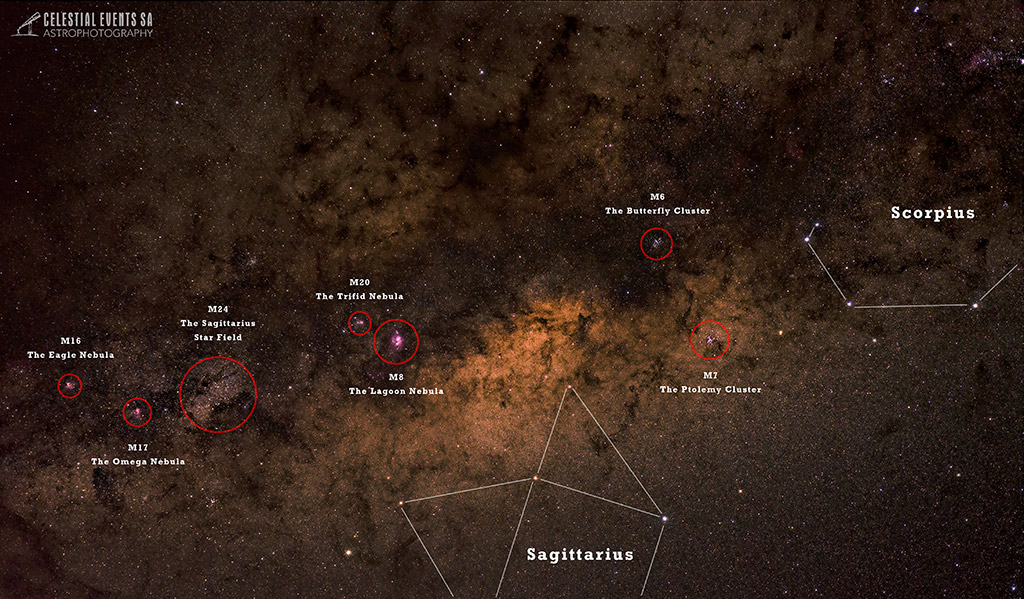

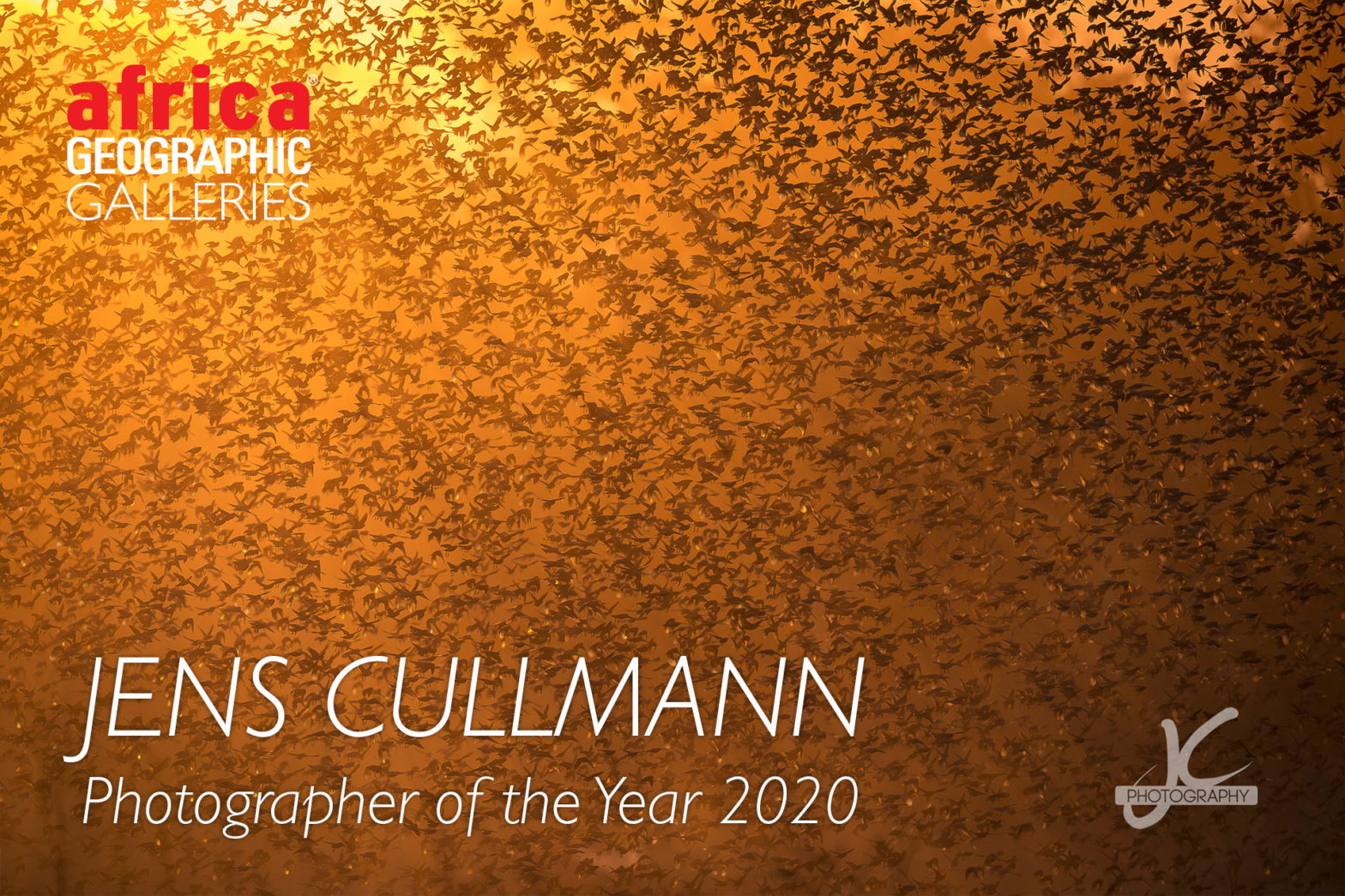

The ‘Pafuri Triangle’ refers to the triangular wedge of land at the Limpopo and Luvuvhu Rivers’ confluence, where forests of massive nyala trees and bright yellow fever trees thrive on the wide alluvial river floodplains. This wedge of land pulsates with biodiversity and is arguably Kruger’s best birding hotspot. Twitchers arrive to pursue Pel’s fishing owl, racket-tailed roller, grey-headed parrot and African finfoot – amongst other avian jewels.

In 1950, a Zambezi shark was caught at the two rivers’ confluence, having worked its way upstream from the Mozambique coastline. Wrap your mind around that nugget of amazingness!

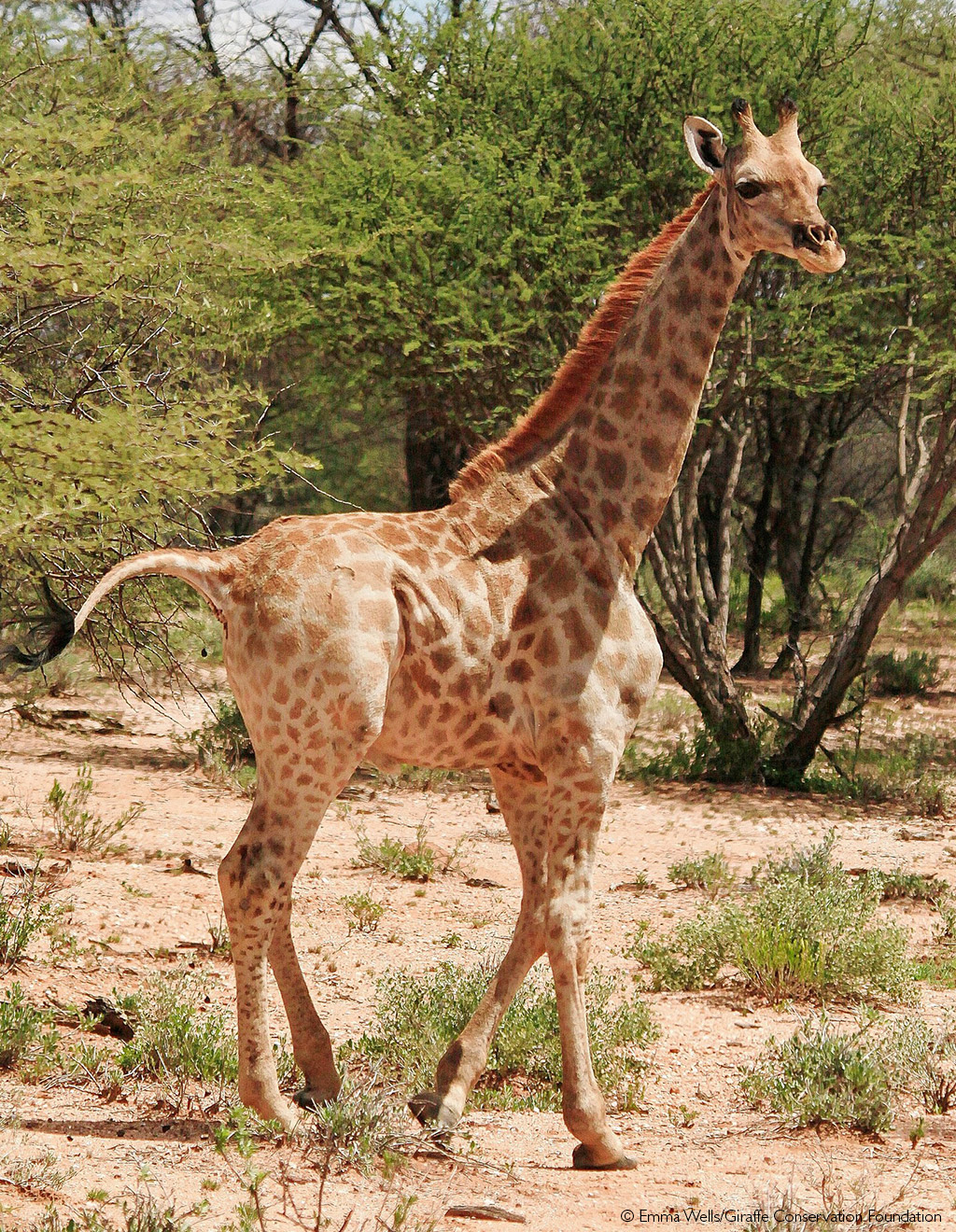

The Big-5 are certainly present, although if this is your key pursuit, you are best served further south in the Kruger. That said, the concentration of huge elephant bulls and the presence of large herds of buffalo on the banks of the Luvuvhu River in the dry season make walking an exciting experience!

On its journey to meet up with the Limpopo, the powerful Luvuvhu River has carved its way through sandstone to create the breath-taking Lanner Gorge with its towering cliffs and steep-sided valleys – another biodiversity hotspot.

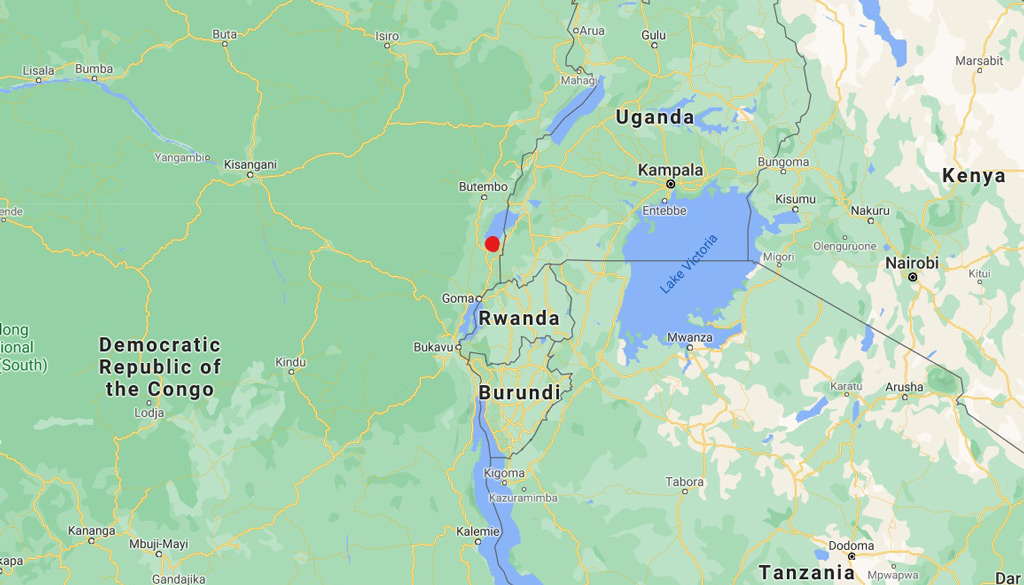

The two rivers meet at Crooks’ Corner, where the triangle’s tip marks the meeting of South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. This unique bottleneck offers a crossing point between these countries for both wildlife and people.

CROOKS’ CORNER

Legendary tales abound about this celebrated region – a hub of wildlife and human activity. During the 1900s Crooks’ Corner was a safe-haven for gun-runners, poachers and other fugitives who would hop over the border when the long arm of the law threatened to catch up with them in either country.

Another nefarious activity that flourished in this wildland was ‘blackbirding’ – recruiting local tribesmen to work under appalling conditions on the South African mines.

The infamous elephant poacher and blackbirder Cecil Barnard was said to have hidden on an island in the middle of the Limpopo River to avoid arrest and confiscation of his ill-gotten ivory. Barnard, nicknamed ‘Bvekenya’, or ‘he who swaggers while he walks’, was the main character in TV Bulpin’s book The Ivory Trail. Notwithstanding the Colonial-era perspective of criminals like Barnard as adventurers and respected characters, he and his kind were as destructive for Africa’s wildlife as modern-day poachers and wildlife traffickers. There were warrants of arrest issued against Barnard from all three countries, and it is believed that Crooks’ Corner was so named primarily because of his presence and activities in the area.

Barnard plundered the area for 19 years and killed more than 300 large-tusked elephants during that time. The Ivory Trail describes how Barnard hung up his rifle in November 1929 after determinedly tracking down the giant elephant known as ‘Dhlulamithi’ (‘taller than the trees’). With the giant elephant is his rifle sites, Barnard decided that “enough was enough” and let Dhlulamithi live.

Today it is perhaps difficult for tourists to fully appreciate the legend that is Crooks Corner, particularly for those reaching this point via the Kruger National Park. Gazing at Zimbabwe and Mozambique on the opposite bank of the wide Limpopo River, you can usually hear cattle and people going about their business. There are no fences and elephants, lions and other dangerous species move between the three countries as a matter of course, so human-wildlife conflict is rife. Poaching is an ongoing problem for conservation authorities. Fireside discussions tell of unscrupulous human traffickers who provide transport to the big South African cities for illegal immigrants that walk across the wide Limpopo riverbed border. So perhaps Crooks’ Corner retains some of its reputation as a safe-haven for unlawful activity.

LAND OF TRANSITION

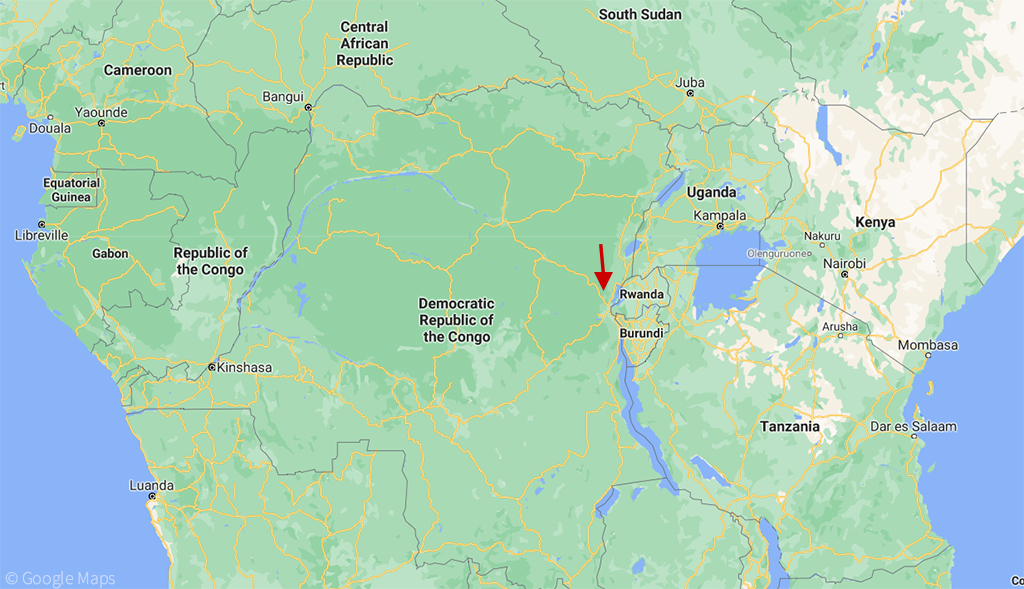

This land has attracted human migrants and occupiers since the Early Stone Age, and the human story continues today. After the Stone Ages (including the San era), the mid-Iron Ages saw the great Bantu migration from the Great Lakes region of East Africa into Southern Africa and the Limpopo Valley in search of grazing for their cattle. The Thulamela period was followed by the ‘Mfecane’ (meaning ‘crushing, scattering, forced dispersal, forced migration’), a period of widespread warfare amongst ethnic communities in southern Africa. It was during this time of upheaval that the forefathers of the Makuleke people arrived in the region.

The Makuleke people lived in scattered villages and practised various forms of subsistence farming and hunting. Crops such as tobacco, millet, sorghum, maize, potatoes, groundnuts, beans, watermelons and pumpkins were grown. Wild harvest included fish, meat, honey, mopane caterpillars, termites and various fruit and berries.

Following a significant Foot and Mouth disease outbreak in the region in 1938-39, the Makuleke were banned from keeping cattle, sheep, or goats. All livestock not secreted into Zimbabwe and Mozambique were killed by the authorities (without compensation).

The land south of the Luvhuvu River was declared as the Shingwedzi Game Reserve in 1903, and in 1933 the Makuleke area was proclaimed as the Pafuri Game Reserve – a provincial reserve under the control of the Kruger National Park. (Read The Kruger History & Future for a better understanding of how the Kruger came about.)

A fence was erected on the north side of the Luvhuvu River in 1961, effectively cutting off the Makuleke people’s access to their natural food sources. However, gaps in the fence permitted access to the river for water.

Then, in 1969, South Africa’s ‘apartheid’ government enforced the removal of the 3,000 followers of Chief Makuleke from the land that the tribe had occupied for more than 150 years. They were moved to Ntlavani – an arid area of equal size outside the Punda Maria gate. Their new homeland was previously part of the Kruger National Park.

This decision was reversed in December 1998 by the post-Apartheid South Africa government, with the first successful land claim. Having won their land back, the Makuleke people agreed to remain in Ntlavani homes and commit their land to conservation objectives. And so was born the Makuleke Contractual Park in the Greater Kruger.

THANKS, SEE YOU AGAIN

“I found the Makuleke area to be vibrant and diverse – a fantastic addition to what Kruger offers further south. The diversity of habitats and species will keep any experienced safari enthusiast buzzing with expectation, and the dramatic human history adds to the romance and nostalgia of this place. The feeling at the camp is one of friendship and family – the staff are clearly proud of their ancestral land and lodge. The game drives through giant fever tree forests, sandy river floodplains and rocky valleys were super-stimulating, and those huge baobab trees that lurk all over the place seemed to beckon to me with whispers of a bygone era. I could have stayed on my private deck all day – with a constant procession of elephant bulls and dagga boys below me harvesting the fallen anna tree seed pods and crunching them like pork crackling. But of course, I didn’t. Next time, for sure.” – Simon Espley – CEO, Africa Geographic

Also read Simon’s account of a special experience at the nearby walled kingdom of Thulamela.

YOUR VISIT TO THULAMELA

During his research for this story Simon was hosted by RETURNAfrica at Pafuri Luxury Tented Camp. This exquisite camp stretches along the Luvuvhu River under the shade of huge trees, with each of the 19 privately positioned tented units accessed via a raised wooden walkway.

The other RETURNAfrica camps in the Makuleke Contractual Park:

Baobab Hill Bush House is an exclusive-use homestead perched on a ridge overlooking the Luvhuvu River – for private groups of up to 8 people on a catered or self-catering basis.

Pafuri Walking Safaris is a seasonal bush camp that acts as a base for walking safaris in this iconic landscape.

Check out our preferred camps & lodges for the best prices, browse our famous packages for experience-based safaris and search for our current special offers.

Jamie Paterson – Scientific Editor at Africa Geographic

Jamie Paterson – Scientific Editor at Africa Geographic

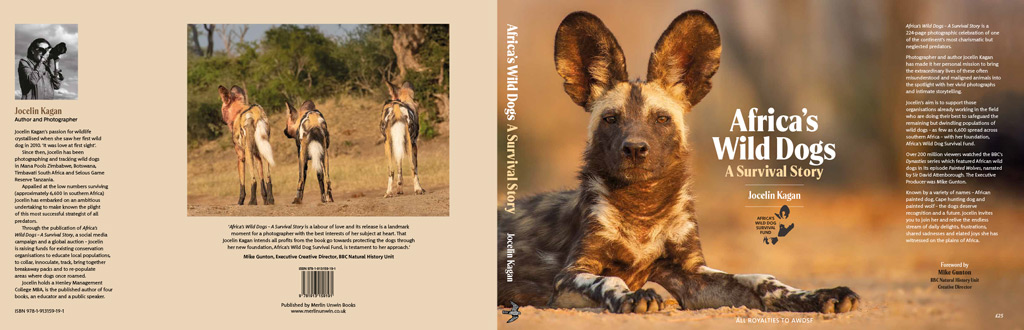

Jocelin Kagan’s passion for wildlife crystallised when she saw her first wild dog in 2010. ‘It was love at first sight’. Since then, Jocelin has been photographing and tracking wild dogs in Mana Pools in Zimbabwe, Botswana, the Timbavati in South Africa, and the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania. Jocelin has embarked on an ambitious undertaking to make known the plight of this most successful strategist of all predators. She holds Higher Primary Teacher’s Diploma with specialization in Speech & Drama from the University of Cape Town, a Master Practitioner Certification in Neuro-Linguistic Programming and a Henley Management College MBA, and is the published author of four books, an educator, and a public speaker.

Jocelin Kagan’s passion for wildlife crystallised when she saw her first wild dog in 2010. ‘It was love at first sight’. Since then, Jocelin has been photographing and tracking wild dogs in Mana Pools in Zimbabwe, Botswana, the Timbavati in South Africa, and the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania. Jocelin has embarked on an ambitious undertaking to make known the plight of this most successful strategist of all predators. She holds Higher Primary Teacher’s Diploma with specialization in Speech & Drama from the University of Cape Town, a Master Practitioner Certification in Neuro-Linguistic Programming and a Henley Management College MBA, and is the published author of four books, an educator, and a public speaker.

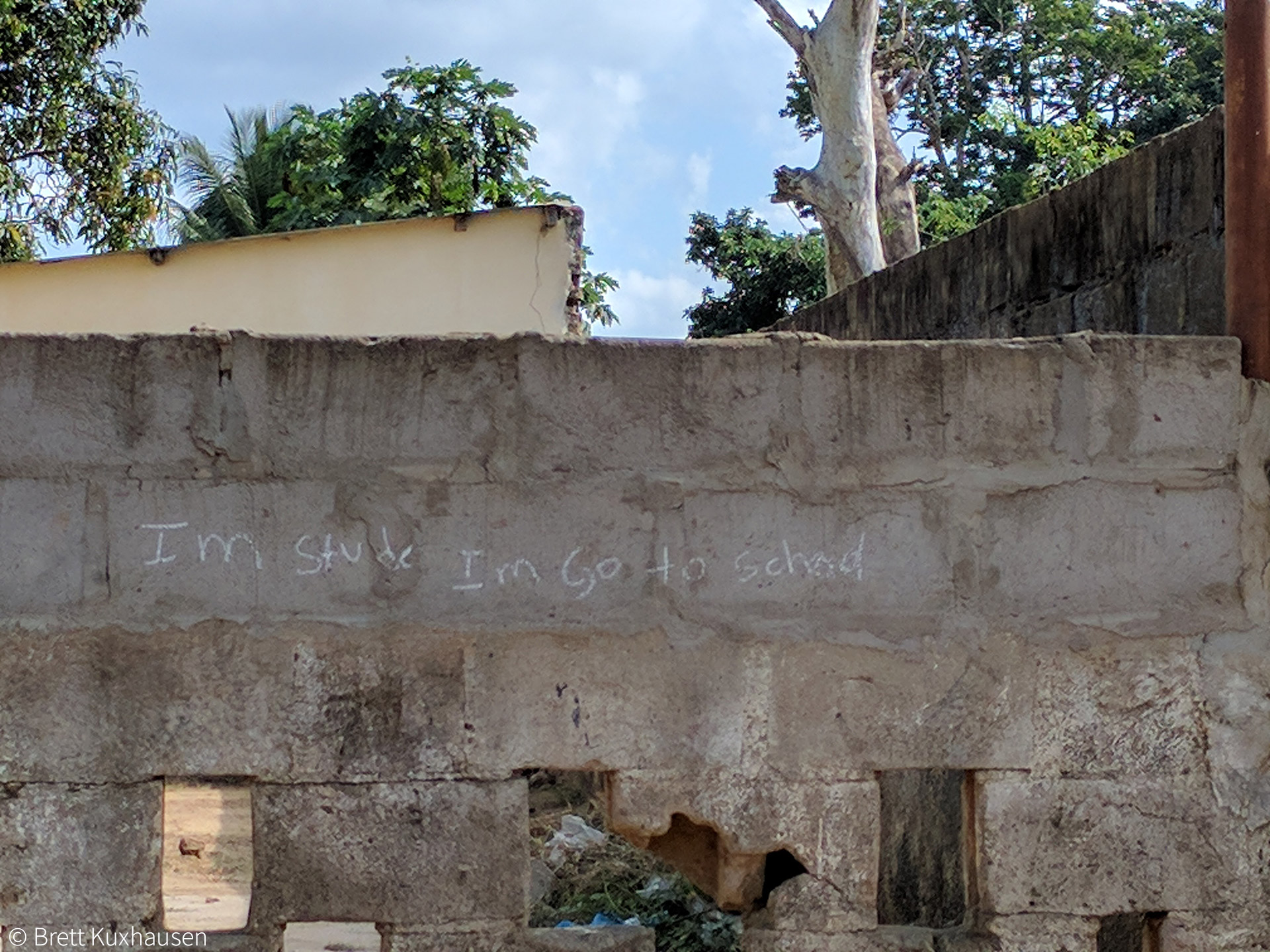

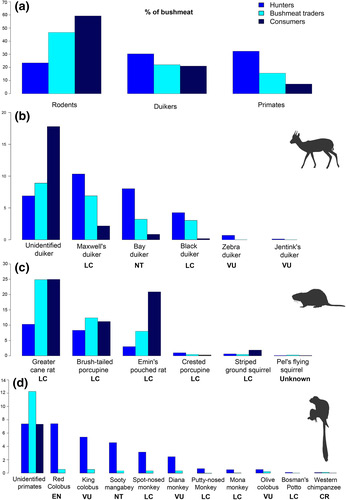

The study suggests that while the development, educational and cultural strategies currently broadly applied to control bushmeat consumption have the potential to be effective, they need to be directed at the correct groups of people in the correct manner to avoid wasting scant resources. While there is an understandably urgent need to protect certain species from unsustainable hunting, policies need to be tailored for each specific species. The authors emphasize that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution to bushmeat consumption and strategies that aim to have conservation benefits need to be based on research that provides a clear understanding of the process within each community.

The study suggests that while the development, educational and cultural strategies currently broadly applied to control bushmeat consumption have the potential to be effective, they need to be directed at the correct groups of people in the correct manner to avoid wasting scant resources. While there is an understandably urgent need to protect certain species from unsustainable hunting, policies need to be tailored for each specific species. The authors emphasize that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution to bushmeat consumption and strategies that aim to have conservation benefits need to be based on research that provides a clear understanding of the process within each community.

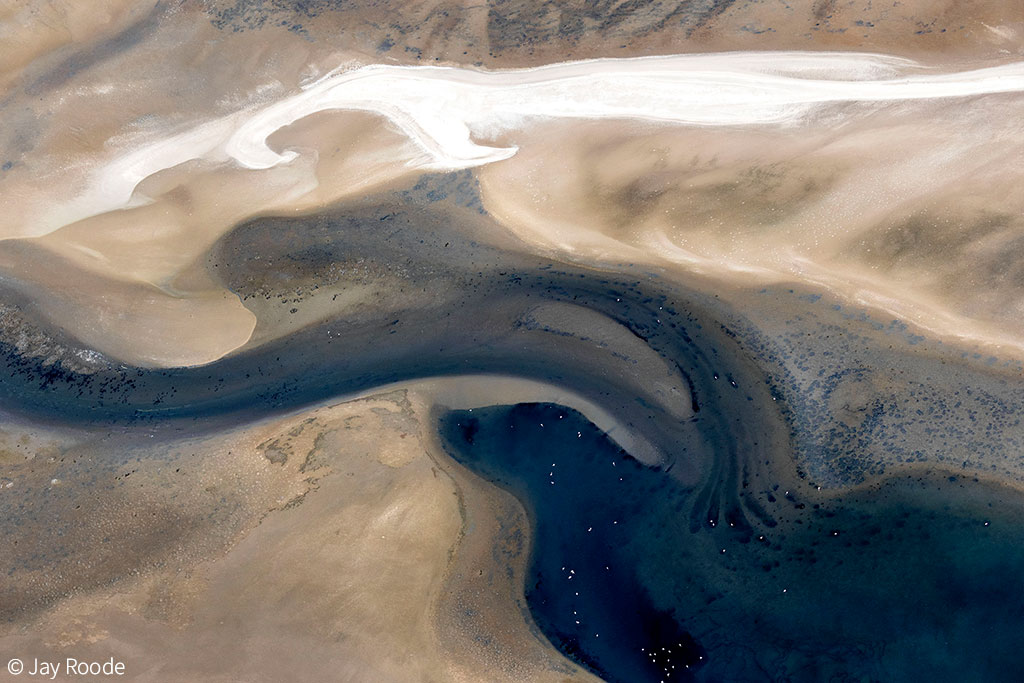

Flying thousands of hours in their specially modified aircraft, aerial photographers Jay and Jan Roode have spent more than a decade photographing some of the most remote and spectacular wilderness areas of Southern Africa from above.

Flying thousands of hours in their specially modified aircraft, aerial photographers Jay and Jan Roode have spent more than a decade photographing some of the most remote and spectacular wilderness areas of Southern Africa from above.