Africa’s Big Tuskers

Please note that we do not provide names or specific locations of any living elephants featured in this issue – for security reasons. We call on our community not to speculate about the location or names of those elephants, and to join us in celebrating these treasures for what they are – African icons

Tuskers are elephants with tusks that reach the ground. According to Rowland Ward’s records, the heaviest tusk of an African elephant weighed an astonishing 226lb (102.5kg), the heaviest tusk of a woolly mammoth weighed 201lb (91.2kg) and the heaviest tusk of an Asiatic elephant weighed 161lb (73kg). However, it is essential to note that the longest tusks are not always the heaviest, as weight also depends on the circumference of the tusks.

Lengthwise, the longest African elephant tusk measured around 3.5m, the longest woolly mammoth tusk measured around 4m and the longest Asiatic elephant tusk measured around 3m.

Unfortunately, hunters very much prize the so-called “hundred pounders” – elephants whose tusks weigh at least 45kg each. As a combined result of trophy hunting, large scale exploitation of ivory for consumer goods in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and devastating poaching, big tuskers have almost been wiped off the African continent. Once a common sight, roaming far and wide across East, Central and Southern Africa, now there are very few big tuskers left on the whole continent.

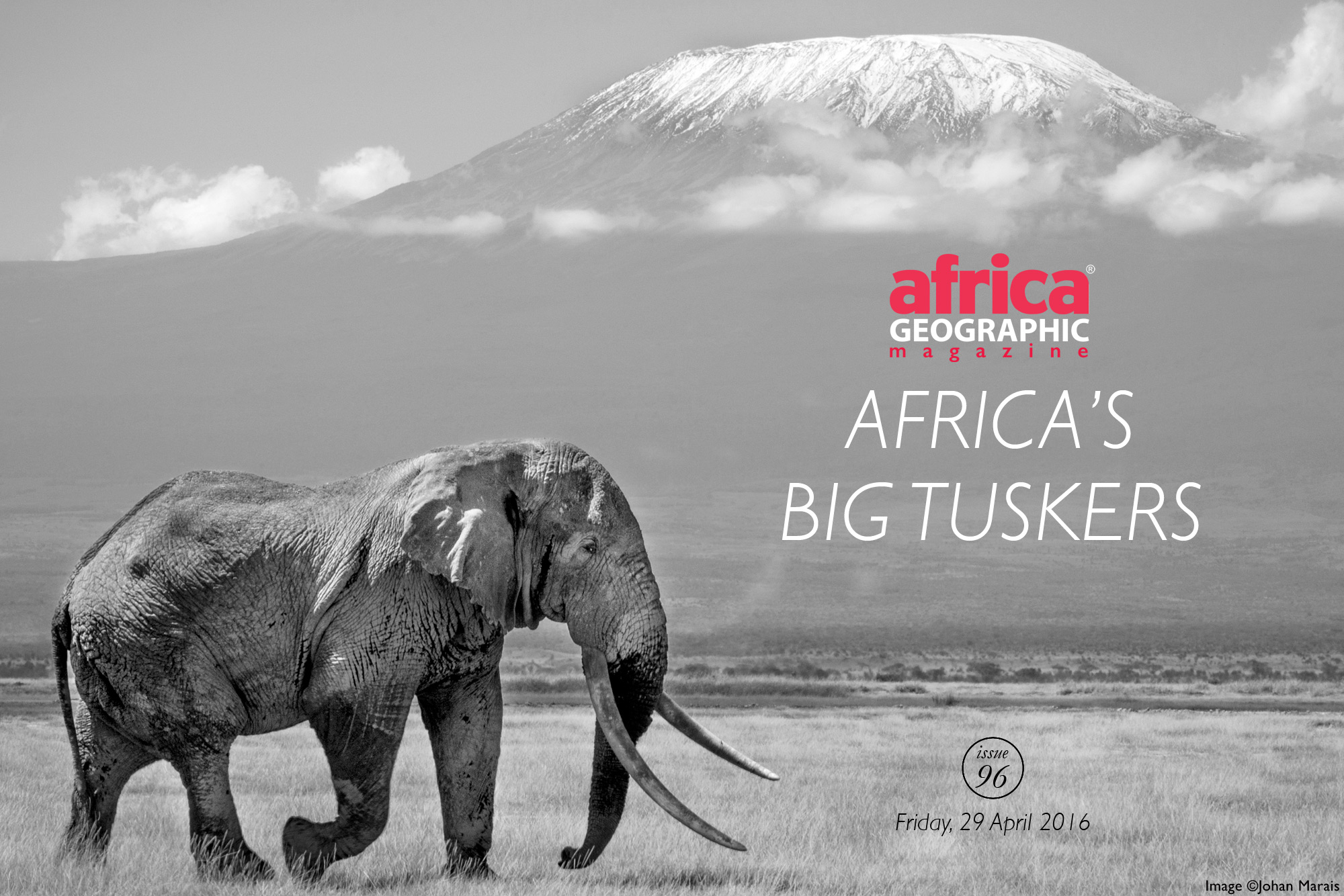

In the above cover photo, you can admire an iconic big tusker against a spectacular backdrop. Now around 47 years old, this fine bull is just about to exit his prime, which is a period generally between 40 and 50 years old when big tuskers reach their peak reproductive age, as well as the climax of their power. This age coincides with the most pronounced growth of their tusks, which means that a lot of bulls draw unwanted attention during these years.

These elephants are like no others. They have captured our imagination. Big tuskers have become incredibly special and, almost two years after the death of Satao at the hands of poachers, we hope that this gallery not only celebrates the existence of big tuskers but does justice to their majesty as the very last of their kind.

In November 2014, this elephant was treated from a wound that was probably caused by poachers, which further highlights how stringent measures need to be taken to protect these amazing animals. A combination of solutions, including constant surveillance, armed protection, relocation and artificial insemination programmes, is arguably the way forward. As Satao’s tragic death has proven, simple armed security is not enough, and big tuskers need armed guards to monitor them 24/7 – a similar protection to that which was enjoyed by an iconic bull called Ahmed in the Marsabit National Park in Kenya in the 1970s.

Contrary to what could easily be believed due to the number of good pictures taken with elephants out in the open, elephants – and in particular big tuskers – spend much more time in the bush than in grasslands. Big tuskers can be seen out in the open in the emerald season when the grass is tender, or in the dry season when they visit marshes and congregate at waterholes. Otherwise, they stay deep in the bush and are difficult to see.

The magnificent tusker in this picture is 44 years old and big – both in body size and tusk size. This particular picture was taken on a walking safari less than 20 metres away. We were following a group of bulls in the bush when the biggest of them suddenly came out of nowhere, raised his head and spread his huge ears, staring at us. He seemed as surprised as we were. We stopped, and he did not charge. He maintained this posture for a few seconds, then disappeared in the same way that he came.

This elephant is the oldest sister of another renowned big tusker, who is probably the most photographed big tusker in East Africa. Born in 1967, she grew up alongside two males – who are now also big tuskers – until the boys left the family when they were around 14 years old. The genes in that family are simply astounding!

This elephant became a matriarch of her herd in 2003, and at the beginning of 2012, she became the mother of a young calf, which can be seen suckling in this picture.

She is exceptional because she is one of less than ten female big tuskers that have been seen in Africa in recent years. While only male Asiatic elephants can grow very long tusks, male and female African elephants can grow such impressive ivory. However, the tusks of the males are generally much longer, thicker and several times heavier than those of the females, which rarely exceed 25kg each.

This legendary tusker from the African rainforest belongs to a smaller sub-species of the African elephant, which can only be found in the equatorial forest. His tusks display the typical forest elephant shape, growing almost straight downwards and parallel to each other. In this respect, they are similar to the tusks of a walrus. As seen in this photo, the gigantic tusks are helpful tools used together with the trunk for digging and extracting minerals in forest clearings.

However, such tusks are highly prized by poachers and trophy hunters, who have decimated forest elephant populations. In a recently published article, the author confirmed that we have lost 62% of forest elephants in the past decade alone. DNA analysis of recently confiscated tusks from Africa revealed that most of them originated from certain forested areas in Central Africa and bushy areas in southern Tanzania.

Like most of the big tuskers, this elephant has a peaceful character and normally avoids conflict. However, he knows how to assert himself when necessary. This was the case when this particular picture was taken, as he prevented other elephants from joining him at the waterhole, making an exception just for this smaller, weak elephant.

? © George Dian Balan

Some big tuskers are born with only one tusk, while others break their tusks while using them. The bull in this photo is still alive and well, and according to local researchers, he was probably not born with only one tusk, but instead broke one of his tusks at some point in time.

This particular picture was taken during a joint operation of the Kenyan Wildlife Service and the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust while seeking to dart and treat another bull possibly injured by poachers. While the other bulls ran into the bushes, this one remained until the end – giving the impression that he wanted to protect the others somehow and cover their retreat. He disappeared into the bushes, and the targeted bull was finally darted from a helicopter.

This splendid bull was photographed in Tanzania while grazing peacefully together with another bull as, due to the recent rains, the whole area was lush, and food was plentiful. Both elephants seemed very content and were rumbling gently alongside one another.

He is one of the very few bulls that may become a big tusker one day, and it is quite a miracle that he has survived the poaching fury thus far. Local guides do not know much about this particular individual – like most bulls that reach this age and tusk size, he is rarely spotted and lives an elusive life.

© Bobby Jo Clow, The Askari Project

Photos of big tuskers are notoriously tricky to capture as they live secretive lives, and most of them have already passed away.

However, the team at The Askari Project was not to be deterred, and their attempt at this photo started in the darkness of early morning, shrouded in clouds and fog. As the light gradually won the fight with the last shadows of the dark, several elephant silhouettes emerged in the distance.

It took 90 minutes for the bulls to reach the safari vehicles patiently waiting for them. One of the bulls had incredible tusks, far greater in size than any of the other individuals in the group. He took people entirely by surprise when he chose to cross the road directly between the two safari vehicles, offering an unforgettable close encounter.

The Askari Project has been established to raise funding and support for elephant conservation and protect some of Africa’s last big tuskers.

They contribute to the funding of The Tsavo Trust.

© Richard Moller, Tsavo Trust

Kenani, now deceased, is the big tusker who inspired The Tsavo Trust’s flagship Big Tusker Project and the organisation’s logo. As with most big tuskers, he was rarely seen in the open and spent most of the time deep in the dry bush.

It’s no secret that Tsavo National Park has the last notable population of big tuskers in the whole of Africa. To preserve this amazing gene pool, The Tsavo Trust has a special monitoring programme, conducting constant aerial and ground operations, which play a vital role in discouraging poachers and ensuring the timely treatment of any wounded animals. The Tsavo Trust collaborates with the Kenyan Wildlife Service to maximise the security of big tuskers, and it also works with other organisations, like the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, to provide any necessary medical treatment to animals. The Tsavo area is also famous for its small hirola population – the world’s rarest antelope- and for the formerly infamous man-eating lions.

Most elephants in Africa today have small tusks, rather than tusks that are similar in length and weight to the prehistoric woolly mammoths, due to a combined effect of large-scale commercial exploitation, trophy hunting and devastating poaching. The result is the opposite of Darwin’s theory of natural selection, as individuals with the best genes have been systematically exterminated.

The name ‘Babu’ comes from the Swahili word for grandfather, and this iconic bull was the pride of the Ngorongoro conservation area in Tanzania before he passed away. When he rested his head on his tusks, they were so big that he gave the impression that he was ploughing with them.

Although he had an average body size for a bull elephant, Babu was still an awe-inspiring sight thanks to his tusks, which were almost parallel and reminiscent of prehistoric species. Babu passed away from natural causes.

Up until around the age of 20, both male and female African elephants grow at a similar pace. While females then stop growing, males continue until around 40, which explains why great tusks are usually about 80cm taller and two times heavier than fully grown females. An average East African big tusker bull stands at about 3.2m in height at the shoulders and weighs around 6 tonnes. The biggest bull ever shot in Africa, which happened in Angola, was around 4 metres tall and weighed about 11 tonnes.

Duke was once the pride of Kruger National Park and was named after Thomas Duke, who was a ranger based in Lower Sabie at the beginning of the 20th century. Duke was arguably the most photographed big tusker in South Africa as, unlike most big tuskers, he was not shy, and he enjoyed human attention. He passed away from old age in October 2011 at around the age of 58.

South African big tuskers are known for generally having a slightly bigger body size than their East African counterparts, with many of them reaching a shoulder height of an estimated 3.4 metres and weighing around 7 tonnes. That said, the heaviest recorded tusks of any African elephant belonged to a bull that lived in the Kilimanjaro area of East Africa and was shot in 1898.

In elephant society, the role of the big tuskers and old bulls is crucial. For instance, it has been observed in certain wildlife sanctuaries in South Africa that young bulls who left their mothers and families at an early age – or who were raised as orphans by humans and then released back into the wild – can pose more of a threat to other wildlife. Such testosterone-filled bulls may even try to mate with rhinos, sometimes killing them in the process. However, this does not happen in areas where great tuskers and other old bulls still exist, as they will keep the younger bulls under control and educate them when necessary.

© Mark Muller

The iconic Satao was arguably the most handsome of the last big tuskers. His tusks displayed the characteristic shape of African elephants in that they grew laterally forward before turning towards each other. He lived in the Tsavo National Park (Tsavo East and Tsavo West), which meant he was arguably part of the best big tusker gene pool in the whole of Africa. As can be seen in this photo, big tuskers are often accompanied by several smaller bulls – called askaris – with which they form small bachelor herds.

People familiar with Satao reported that he seemed to intentionally hide his tusks behind bushes in a way that made them suspect he was aware that his huge tusks placed him in danger. Whatever the scientific reasons behind this behaviour, it is most certainly a characteristic that I have witnessed concerning several big tuskers.

After falling victim to poachers in May 2014 at the age of approximately 46, the shocking pictures of his carcass made him a symbol of the huge tragedies suffered by African wildlife. His death highlights the failures across the continent to protect these gentle giants, which is something that we need to face and urgently rectify.

Plan your Kenya safari to see tuskers find a ready-made safari, or ask us to build one just for you.

Plan your Kenya safari to see tuskers find a ready-made safari, or ask us to build one just for you.

About the author

George Dian Balan is a wildlife photographer and conservationist who has travelled extensively worldwide searching for the last wilderness sanctuaries. He learned foreign languages in his childhood by reading hundreds of books about wildlife in English and French, years before the ‘boom’ in wildlife documentaries and the massive distribution of wildlife photography through social networks.

George Dian Balan is a wildlife photographer and conservationist who has travelled extensively worldwide searching for the last wilderness sanctuaries. He learned foreign languages in his childhood by reading hundreds of books about wildlife in English and French, years before the ‘boom’ in wildlife documentaries and the massive distribution of wildlife photography through social networks.

Dian is a self-taught photographer who seeks to do justice through his work to the fantastic beauty of wild creatures in their natural environments. His project – The Miracle of Wildlife – is about the miracle of the other wonderful creatures we share Earth with. It is about wildlife photography winning hearts and minds. It is about a gentle walk in the woods, a swim in the ocean, an intrepid expedition in the tropics or a sweaty hike to the top of a snow-covered mountain.

His work has been published by BBC Earth, Wild Planet Photo Magazine and Africa Geographic, among others, and he has also done well in various photography competitions. Dian is one of the few people worldwide who have photographed African and Asian big tuskers. He believes that elephants should be depicted in children’s books with “tusks-to-the-ground” and rhinos with “horns-to-the-sky”, exactly as they were in great numbers before and as very few of them still are.

ALSO READ Time with super tuskers

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()