The forests of West and Central Africa are vibrant, impenetrable worlds of their own: breathing ecosystems bursting with life at every turn yet defined by a pervasive sense of mystery. Enfolded by towering trunks, creeping vines and lush ferns, the forests’ enigmatic creatures flutter through the canopies and wander ancient paths in an increasingly dangerous world at the mercy of human impact. Their largest residents, African forest elephants, are close to the brink of disappearing entirely.

As of March 2021, the forest elephant is officially listed as ‘Critically Endangered’ by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The world’s smallest elephant is elusive and poorly understood while centuries of persecution have made them understandably mistrustful of humans. Our belated recognition of their species status and desperate plight has left scientists and conservationists scrabbling in a race against time to learn more about these grey forest ghosts.

Quick introduction

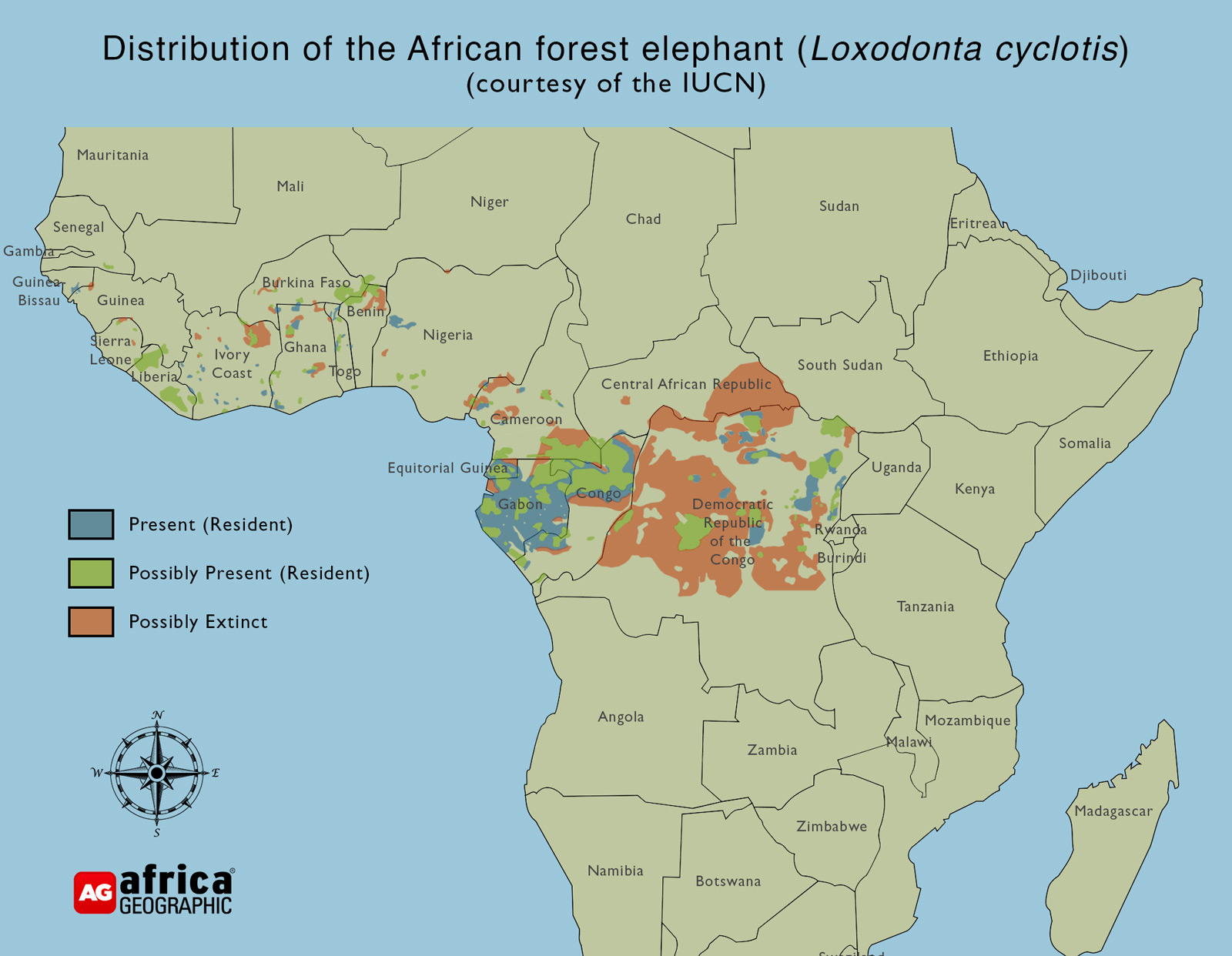

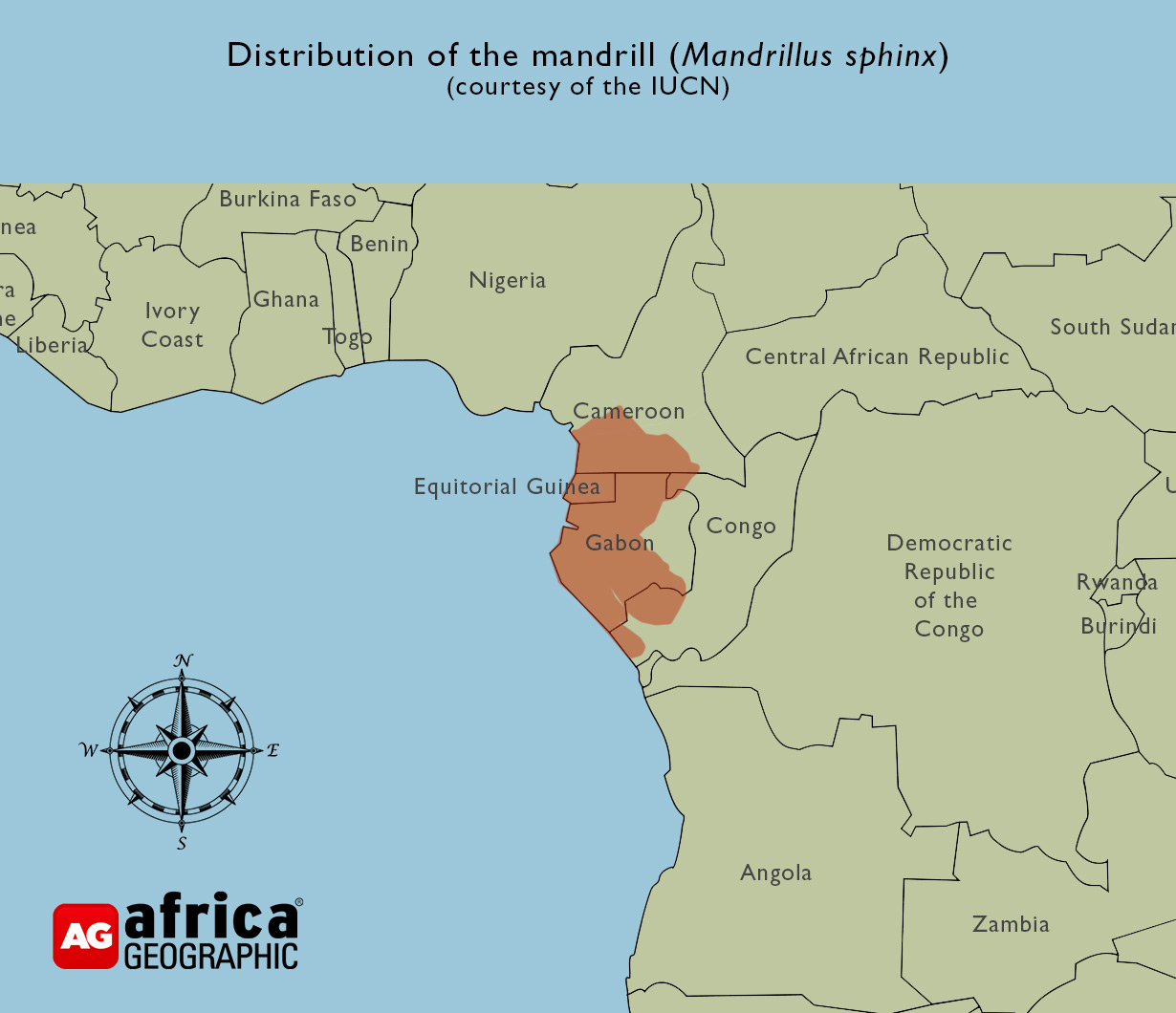

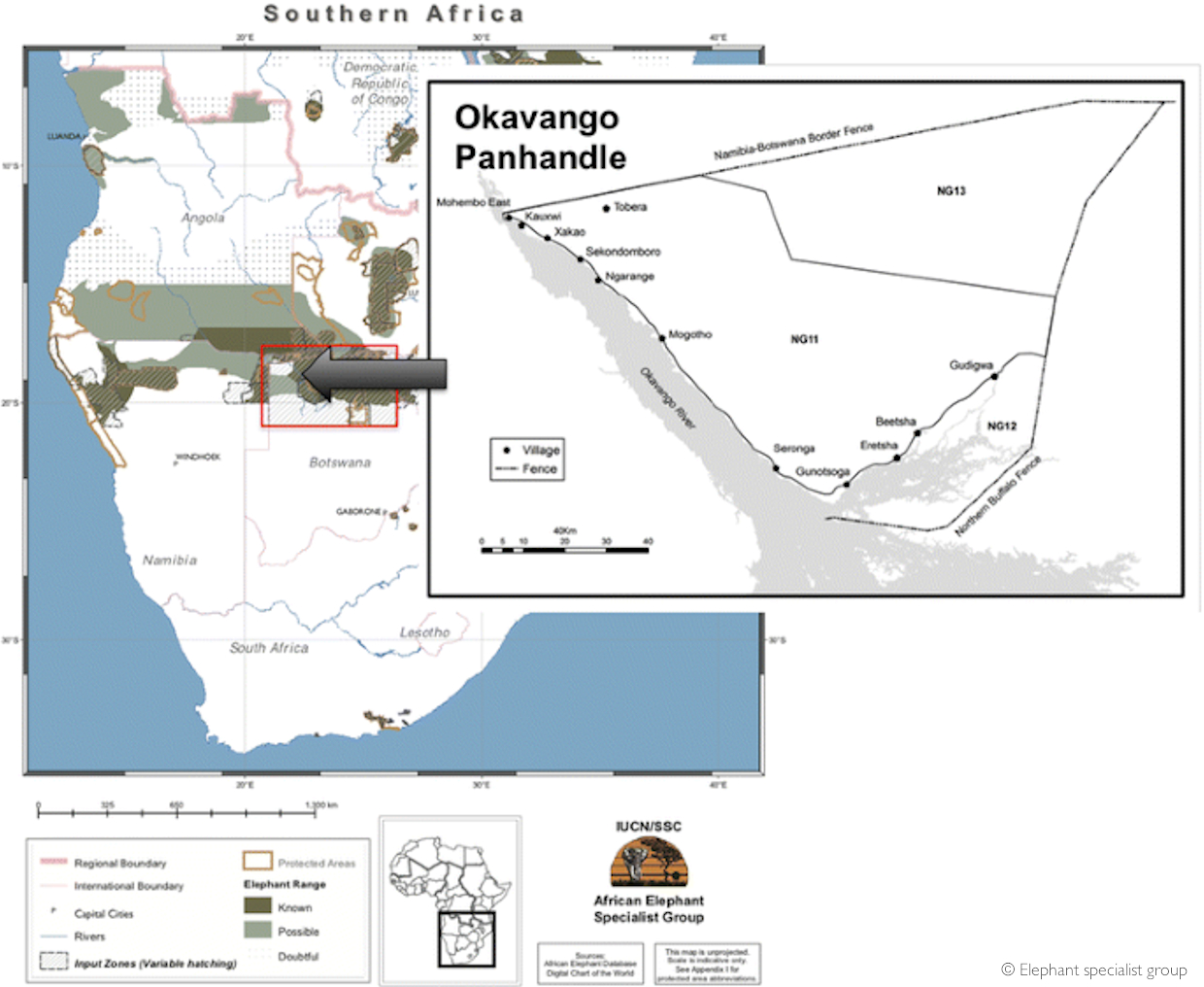

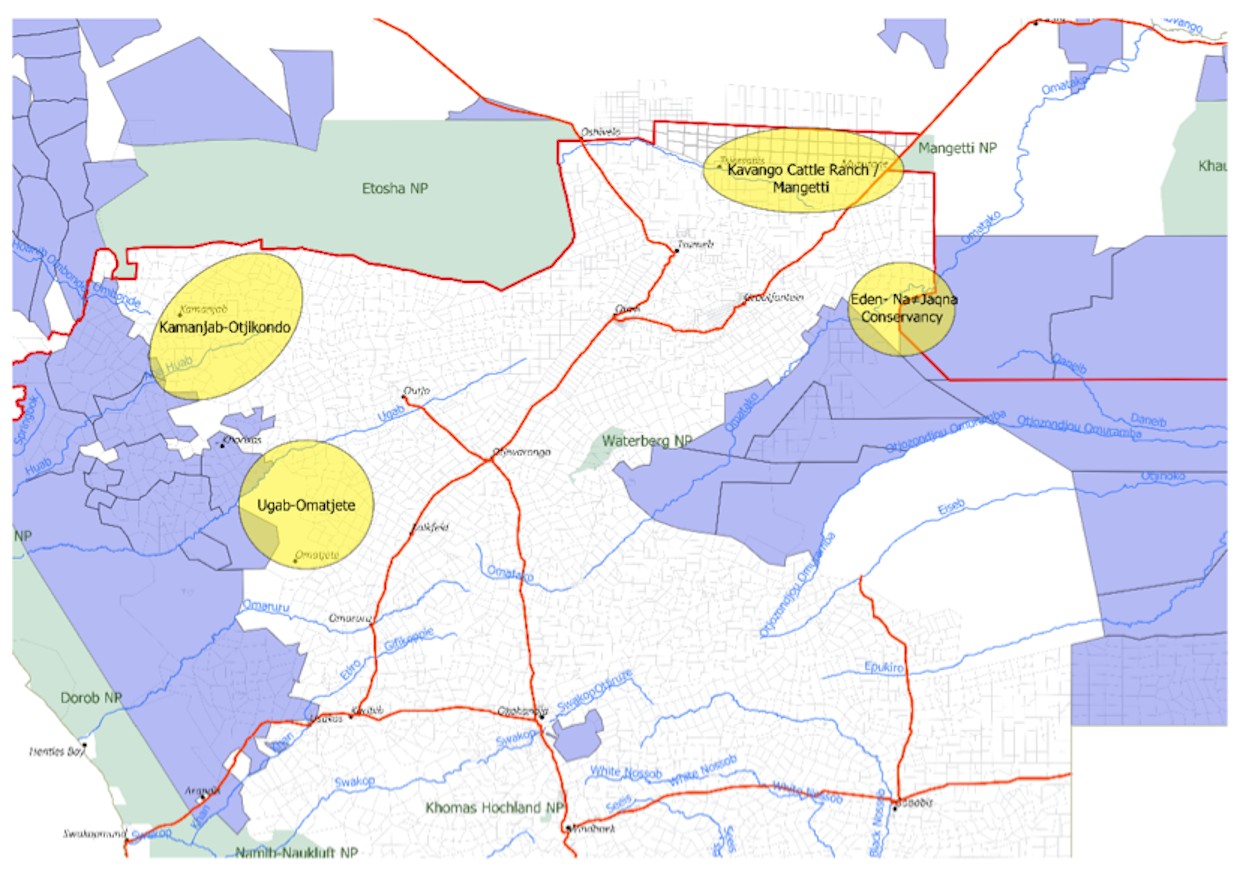

The African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) is one of two African elephant species, mainly confined to West and Central Africa’s forests from Cameroon to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Roughly 72% of the remaining populations are found in Gabon and the Republic of the Congo. Forest elephants are smaller than their savanna cousins (Loxodonta africana – also referred to as the African bush elephant) cousins. Forest bulls rarely exceed three metres at the shoulder and seldom weigh more than three tonnes. (This compared to a big savanna elephant which may reach close to four metres and weigh over six tonnes.)

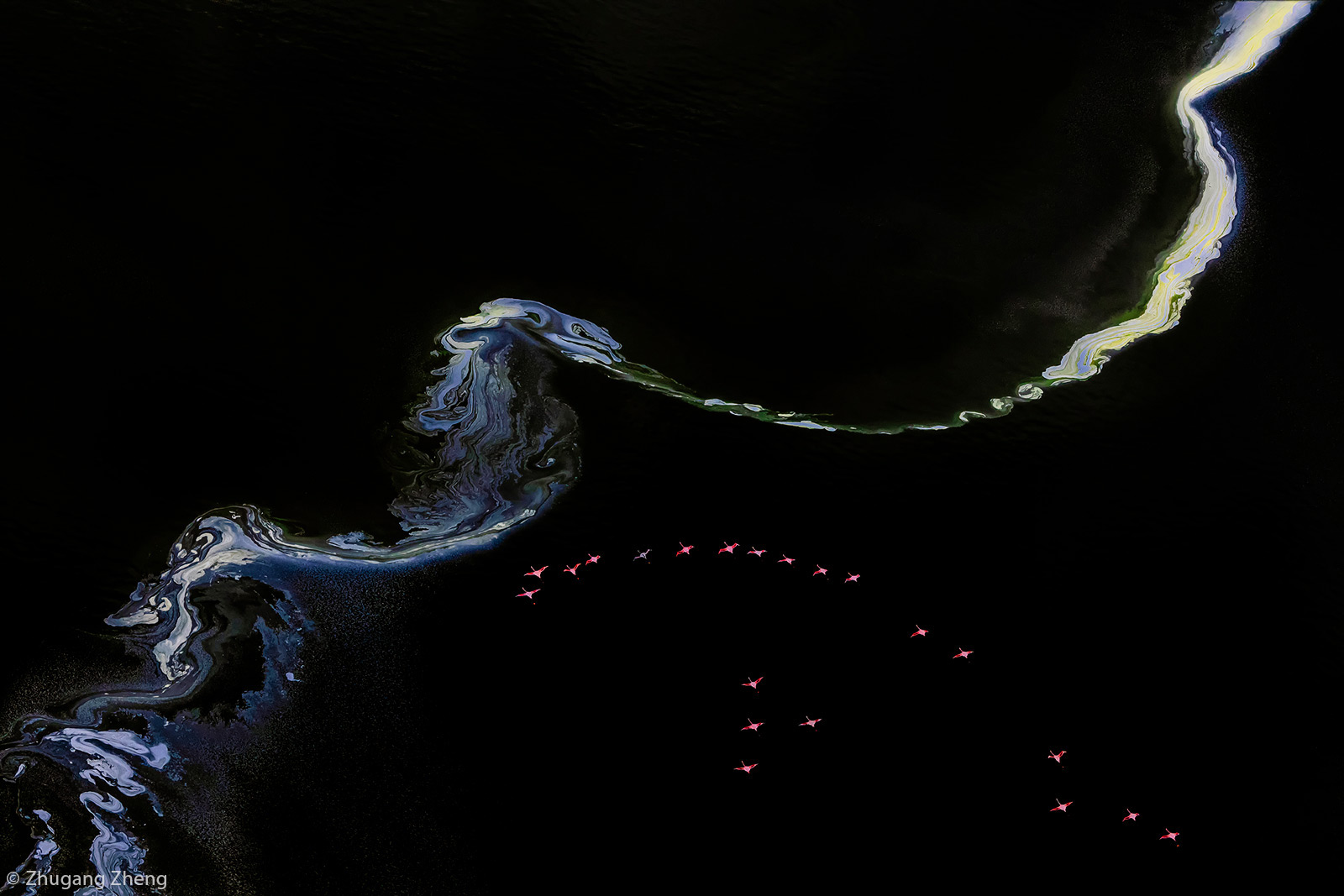

Forest elephants consume an enormous variety of plants and are recognised as essential seed-dispersers in forest ecosystems. Scientists have labelled them “megagardeners” of the forests. Their movements seem to be guided by the ripening of fruits, which occurs at different times in different parts of the forest. They seek out minerals to supplement their diets and are attracted in large numbers to the salty waters of the forest baïs. As a result, much of what we know about forest elephant behaviour comes from observations at these large forest clearings.

For now, our understanding of forest elephants is primarily extrapolated from the extensive behavioural research of savanna elephants, though scientists are now more focused on learning about forest elephant peculiarities. By all accounts, their social structure is similar to that of savanna elephants, with the females living in small family herds, which display “fission-fusion” patterns of behaviour. (That is, they are not territorial and will form temporary associations with other herds or individuals for a while.)

The differences (a summary)

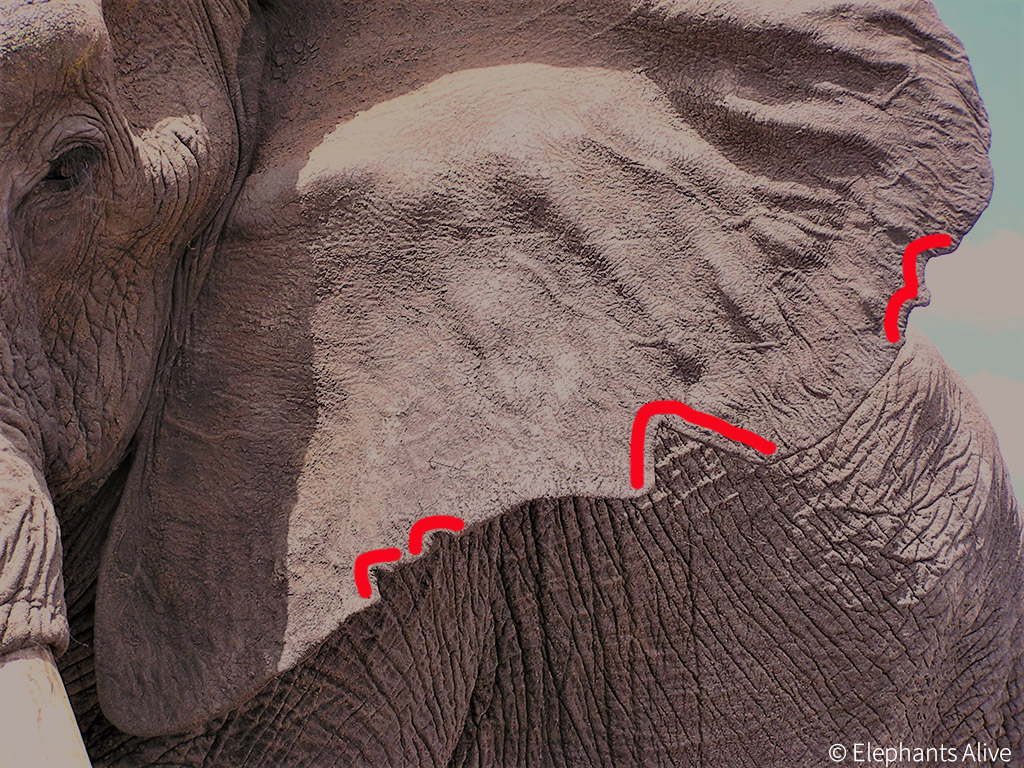

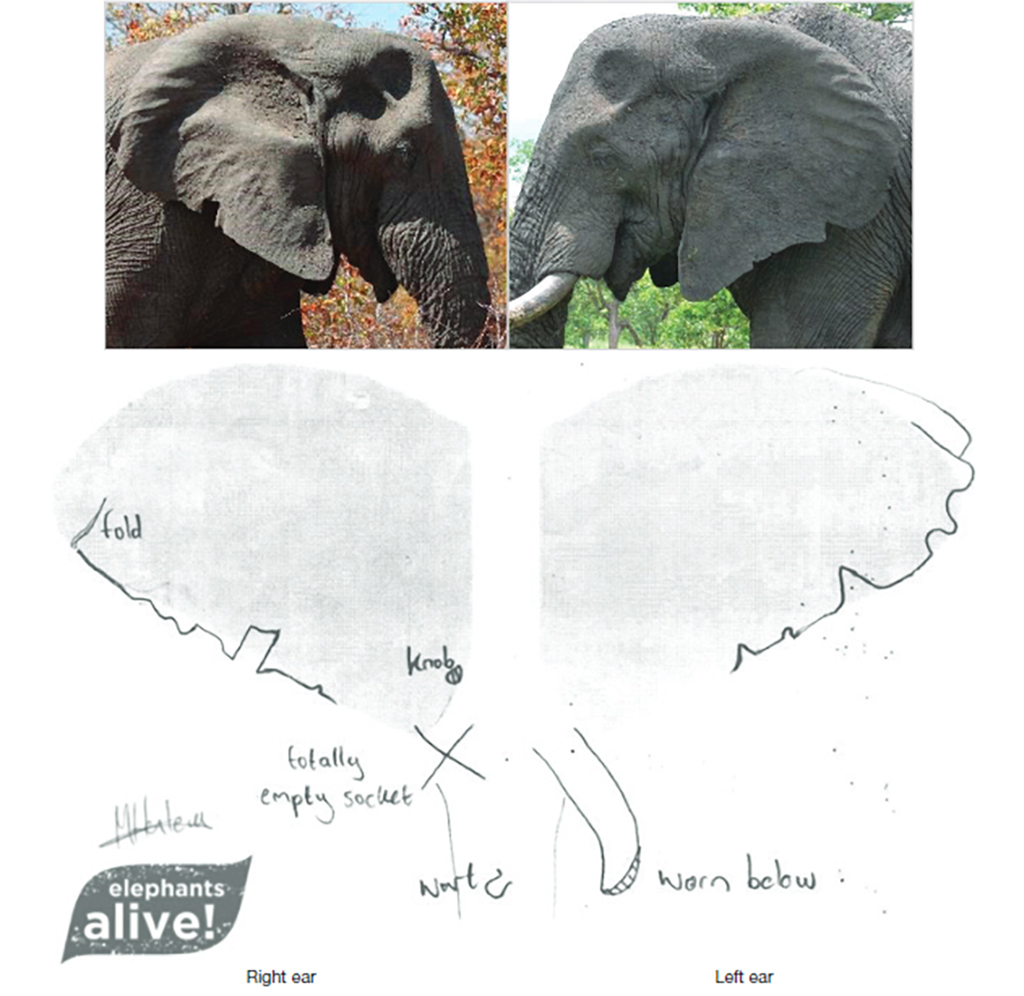

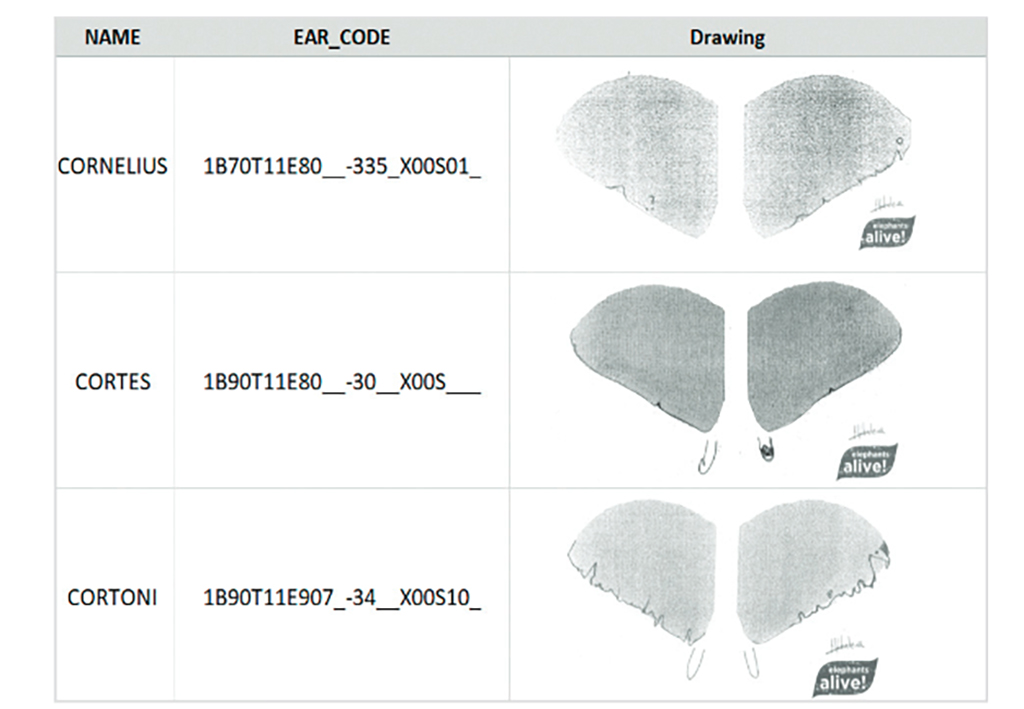

The ears of forest elephants are more oval than those of the savanna variety (hence the specific name cyclotis). The tusks are most distinctive, however, growing relatively straight and usually pointing straight down rather than out. The differences are subtle to the inexpert eye and manifest more as a sense of “something different” when images of the two species are viewed side-by-side. A quick way to distinguish between the two is to count the number of toenails: forest elephants have five on their front feet and four on the hind feet, while savanna elephants only have four on the front feet (occasionally five) and three on the back foot. This method is, of course, contingent on being able to see the feet.

One central behavioural and physiological difference is the breeding age and breeding rate. Savanna elephants usually start breeding at around 12 years old and, under optimum conditions, will have a calf roughly every 3-4 years. In contrast, forest elephants only have their first calves at an average age of 23 and have a birthing interval of up to six years. The estimated population doubling time is roughly triple that of savanna elephants. This intensely slow population growth rate means that it would take approximately a century to recover to their pre-2002 numbers (without continued human impact).

Disappearing ghosts

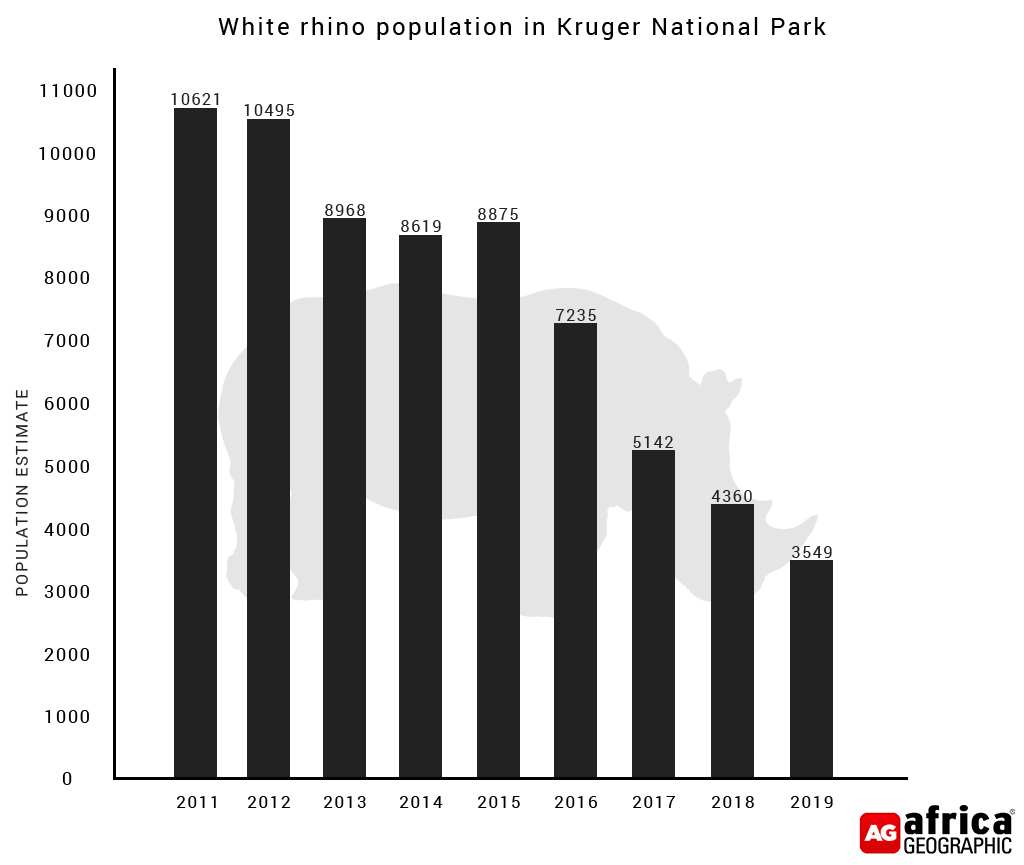

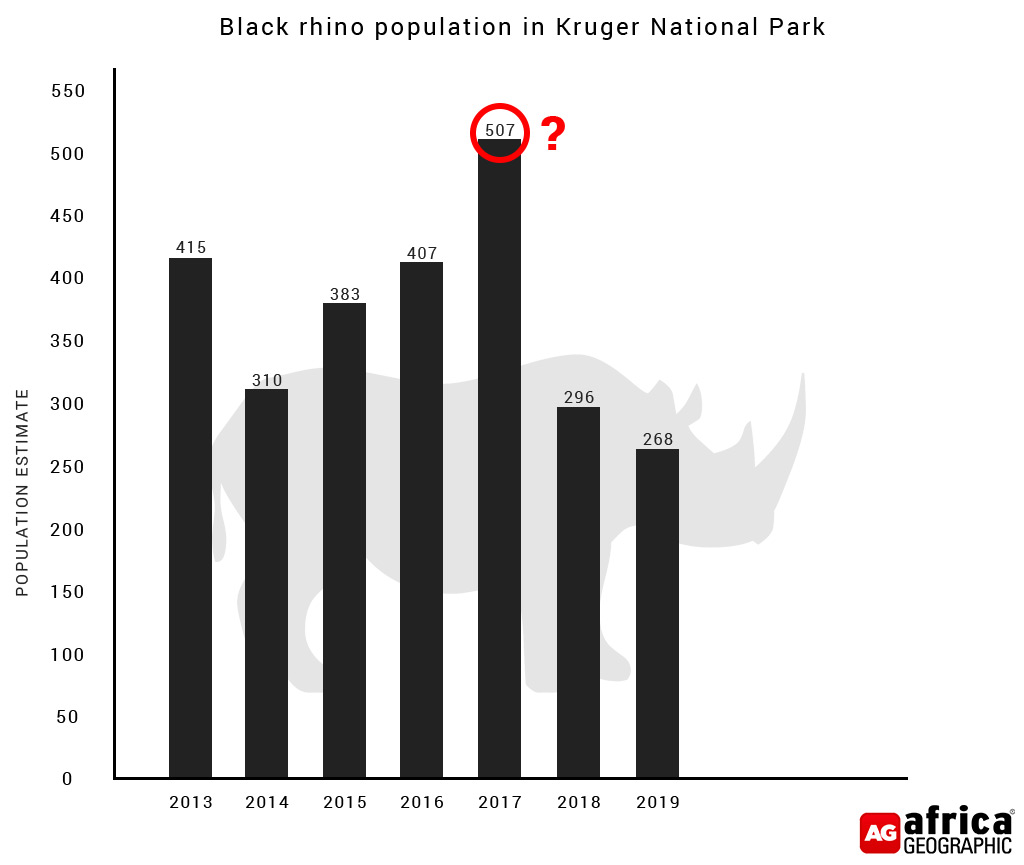

This is a distressing thought, given our current understanding of how forest elephant numbers have declined over the last few decades. There are, at present, no reliable estimates of the overall number of forest elephants throughout their range. Researchers believe that their numbers have crashed by over 86% in the past 31 years. One study revealed that populations had declined by 62% in just nine years, between 2002 and 2011. Before then, centuries of massacres to supply the ivory trade would have resulted in the demise of untold numbers.

In recent years, much of the damage has been caused by a significant rise in poaching, often fuelled by civil unrest in certain countries. According to the IUCN, this remains the single greatest threat to forest elephants. Naturally, most of the poaching is motivated by the ivory trade, and there is a preference in specific markets for forest elephant ivory due to its higher density than that of savanna elephants. In addition, the bushmeat trade likely includes sizeable volumes of elephant meat.

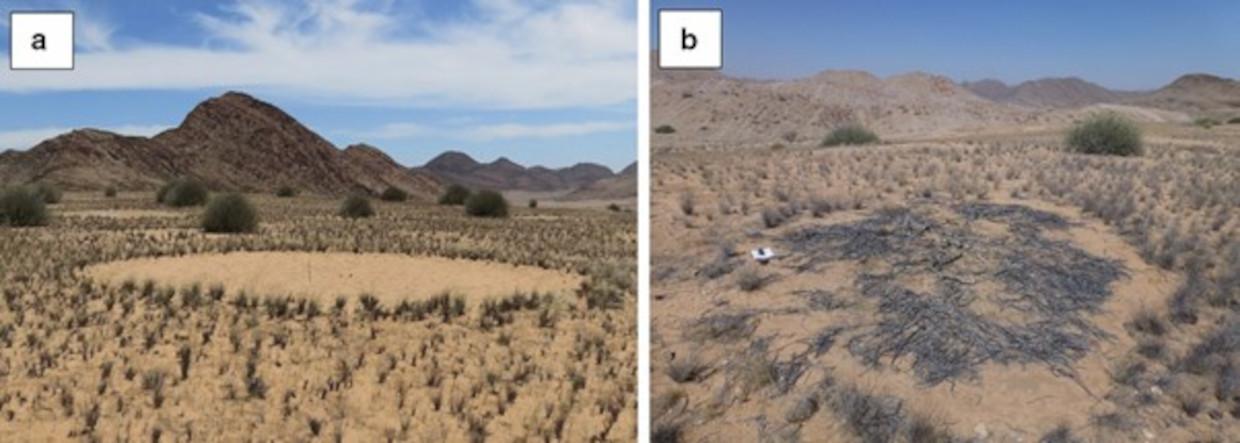

Habitat loss has also been labelled a “silent killer” of forest elephants. The direct loss and fragmentation of their remaining habitats to agriculture, roads and fences are projected to increase in the coming years. Recent research also indicates that climate change may be having unforeseen effects on the physical health of the elephants.

Considering precipitous population declines and irreversible habitat loss, the IUCN’s first official assessment of African forest elephants concluded that they are now critically endangered. (The IUCN also announced the change in the savanna elephant’s conservation status from vulnerable to endangered.)

The third elephant

Given their precarious position, it seems almost bizarre that IUCN recognition of the forest elephant’s status as a separate species took so long. Especially given that genetic scientists had reached that conclusion as early as 2001. Not only are there two different species of African elephant, say recent studies, but they likely diverged between two and five million years ago (depending on the study). This would have occurred around the same time as Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) and woolly mammoths began to diverge. Some researchers argue that the two elephant species may be further removed from each other than lions and tigers and that the split goes back as far as the divergence of humans and chimpanzees.

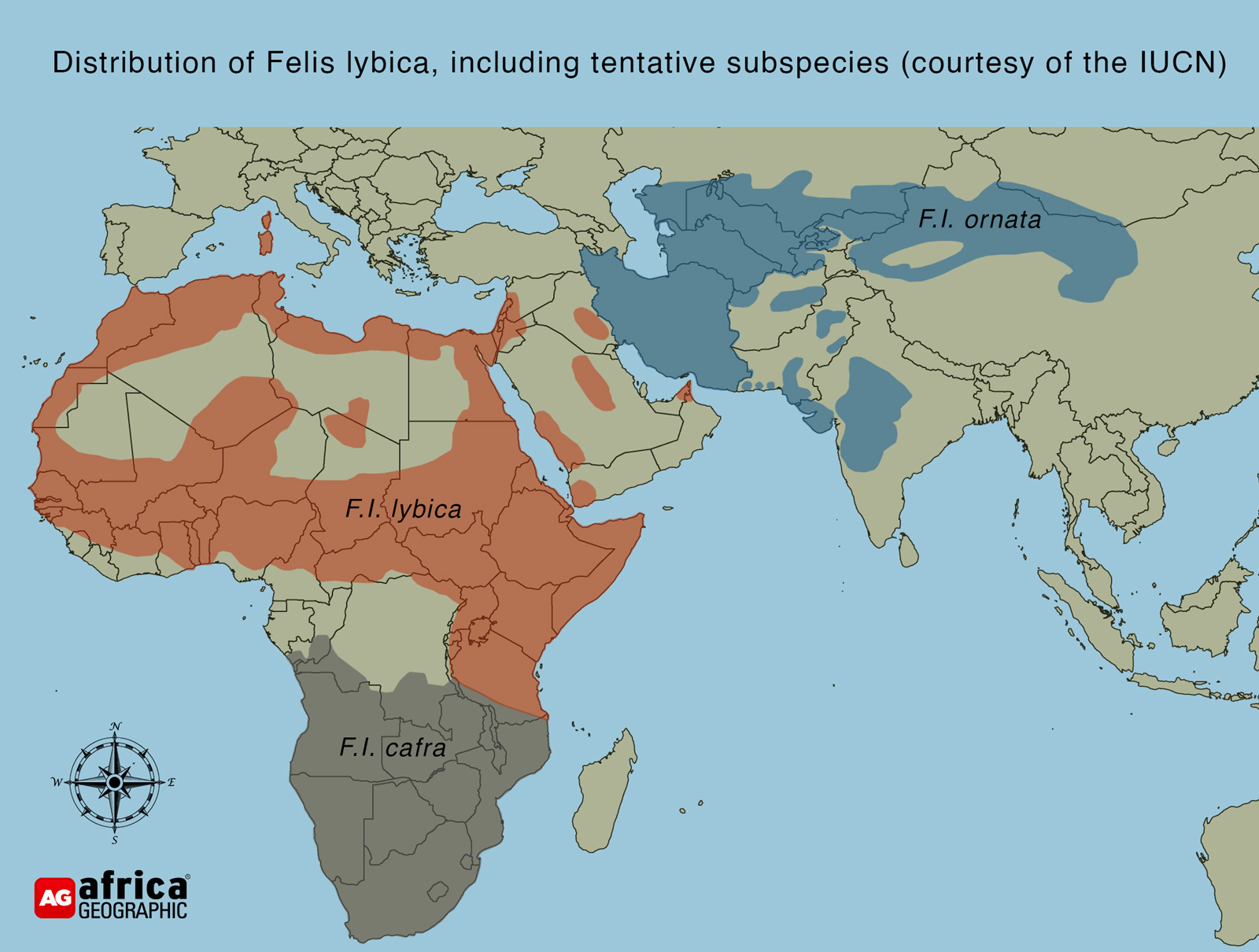

However, the idea that the forest elephant is not a subspecies of the savanna elephant was far from universally accepted or straightforward, not least because there are known hybrids. Tracing any animal’s evolutionary process through existing genetics is no small task. Hybridisation and gene flow between diverging species are common complications. (Classifications of the African golden wolf and domestic cats/wild cats have faced similar challenges). The matter was finally concluded through a series of genetic studies over the last decade and a decisive report on the limited extent of hybridisation.

The elephant in the room

So, what practical impact, if any, does the forest elephant’s new-found IUCN status have? Especially given that most ground-level research and conservation efforts were essentially treating this fact as a given already? The short-term answer is probably that little will change, apart from temporarily catapulting forest elephants onto media pages across the globe. It also begs the question of how many smaller, less iconic species we lose before they are even recognised as separate species.

However, far from being irrelevant, the forest elephant classification is one of the most high-profile examples of how science, international law, and politics all play a role in the conservation of a species. The classification should allow for more nuanced conservation policies, particularly at an international level, and a complete estimate of remaining population numbers is also likely to be forthcoming. Moreover, it changes how savanna elephant populations are measured since forest elephants were included in past counts and probably accounted for around a quarter of previous estimates.

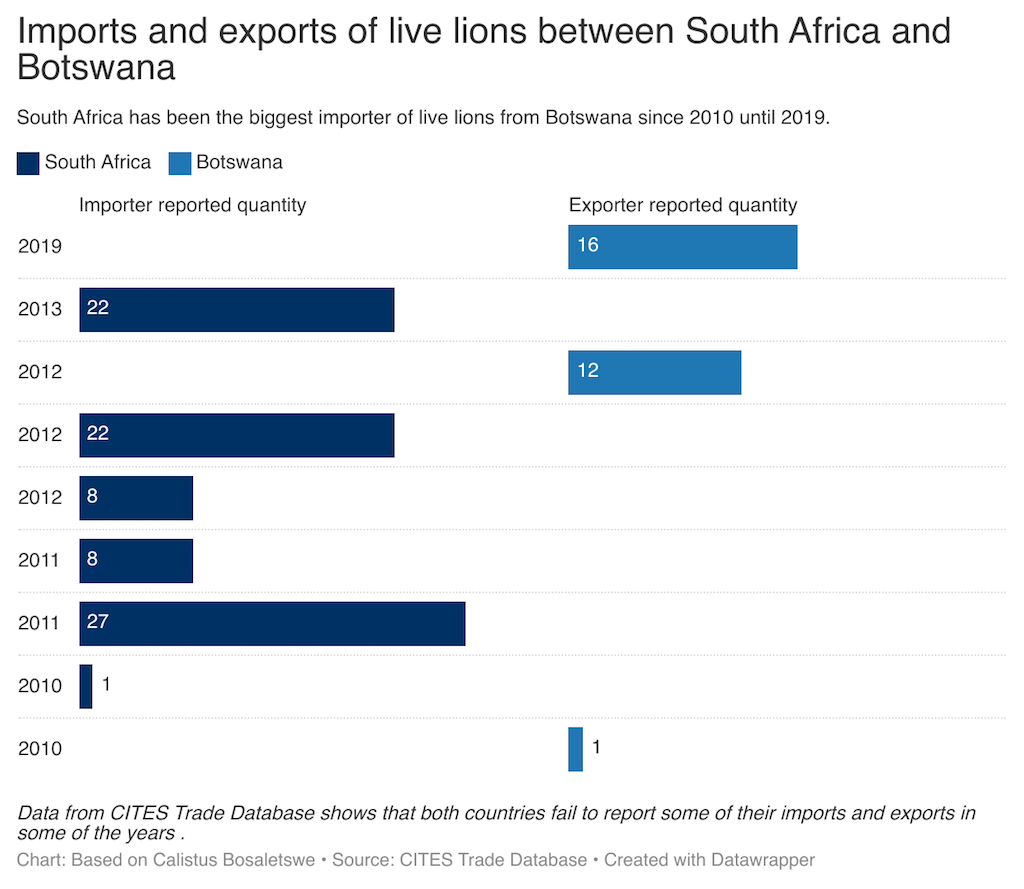

Given that the IUCN informs CITES’ decision-making (which governs international trade in animals), a distinction between the two species should see increased restrictions to make it harder to launder illegal ivory on the legal market.

Hope for the future?

Most importantly, conservationists hope that this new classification will aid in efforts to protect African forest elephants – long overdue though it may be. It is a frightening thought that upon the official recognition of a new elephant species in 2021, it was immediately classified as critically endangered.

Fortunately, there are protected areas where forest elephant populations are stable, if not growing. Though our acknowledgement of their predicament has probably come too late to ever rectify the damage entirely, perhaps their new ‘Critically Endangered’ label will serve to galvanise the international community into action. These magnificent and unique elephants have paid the price for human greed and conflict, and their value has been undermined by the grindingly slow bureaucracy of international conservation politics. If nothing else, this should serve as a very steep learning curve for the future.![]()

The biological travesty that is the Lion King (yes, I know it’s a good story) has created a world of pain for safari guides. Before actual animal behaviour can be discussed, the hapless guide must dissuade his guests of notions like East African dwelling suricates and birds that clean crocodile’s teeth. Let’s not start on the implications of incest that came with Nala and Simba’s nuptials. Possibly the most bizarre addition to the film was Rafiki – a mandrill who had apparently defied science in innumerable ways by coming out of the forests of Gabon to preside over the spiritual well-being of an East African lion pride and its subjects. In our first story below, we set the record straight regarding the fascinating mandrill – a primate who has achieved rudimentary tool use but not discernable contact with the spirit world.

The biological travesty that is the Lion King (yes, I know it’s a good story) has created a world of pain for safari guides. Before actual animal behaviour can be discussed, the hapless guide must dissuade his guests of notions like East African dwelling suricates and birds that clean crocodile’s teeth. Let’s not start on the implications of incest that came with Nala and Simba’s nuptials. Possibly the most bizarre addition to the film was Rafiki – a mandrill who had apparently defied science in innumerable ways by coming out of the forests of Gabon to preside over the spiritual well-being of an East African lion pride and its subjects. In our first story below, we set the record straight regarding the fascinating mandrill – a primate who has achieved rudimentary tool use but not discernable contact with the spirit world.

I am a proud African and honoured to be CEO of Africa Geographic. My travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, elusive birds and real people with interesting stories. I live in South Africa with my wife, Lizz, and 2 Jack Russells. When not travelling or working, I am usually on my mountain bike somewhere out there. I qualified as a chartered accountant, but found my calling sharing Africa’s incredibleness with you. My motto is “Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change”. Connect with me on

I am a proud African and honoured to be CEO of Africa Geographic. My travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, elusive birds and real people with interesting stories. I live in South Africa with my wife, Lizz, and 2 Jack Russells. When not travelling or working, I am usually on my mountain bike somewhere out there. I qualified as a chartered accountant, but found my calling sharing Africa’s incredibleness with you. My motto is “Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change”. Connect with me on