China’s desire for exotic animals, tastes and products will probably push wild elephants, rhinos, pangolins and many other species to extinction within the next 10 to 15 years. Asia’s Golden Triangle is the epicentre of the problem. Written by: Don Pinnock

This trade destabilises many African countries as poachers, armed by organised criminal syndicates, outgun security forces, loot villages and decimate animal populations. Their bloody haul is mostly transported by Asian agents who bribe officials and undermine the security of national states.

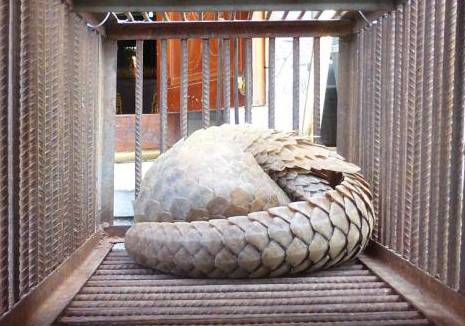

We begin in the lawless, drug-soaked jungles of Asia’s Golden Triangle. In the jungle along the Mekong River is a palatial casino named Kings Romans where you can order freshly killed bear cub steak, grilled pangolin, tiger penis or gecko fillet, and wash it all down with wine matured in a vat containing lion bones.

The shop offers rhino horn libation cups and bracelets or, for more conventional tastes, religious sculptures and jewellery made from poached African ivory. After a night at the gambling tables, you can pay a beautiful young woman to accompany you to bed. Chinese guests are preferred.

However, if you cannot settle your gambling debts, you will be locked in the local jail until your relatives pay. If they don’t, you could, apparently, be led into the jungle and shot.

Kings Romans is one of a number of such establishments in the Golden Triangle, thickly forested borderlands between Laos, Thailand, Myanmar and China. It’s an area of lawlessness and rebel armies from which much of the world’s heroin and amphetamines come. Similar ‘resorts’ include Allure, God of Fortune, Fantasy Garret, Regina, Mong Lah and Boten.

The Golden Triangle is a conduit of death for an unimaginable number of Africa’s iconic animals.

This information is offered matter-of-factly over a cup of coffee in Cape Town’s Waterfront by an unusual Kenya-based undercover investigator and self-confessed troublemaker named Karl Ammann. Unusual because he works alone and digs out explosive information, often at a considerable financial cost to himself. A troublemaker because he’s uncompromising in exposing wildlife traffickers, as well as governments and respected international conservation organisations, when they become part of the problem.

His motivations – an inquisitive nature and a fierce desire to protect wildlife – are often suspect because he has no political or organisational affiliations. He’s an elegant, widely-travelled, deeply knowledgeable, principled maverick. Not to mention the delightful company. But how reliable was his information? Corroboration came from a startling report, Sin City, completed last year by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) in conjunction with Education for Nature Vietnam.

“Laos,” begins the report, “has become a lawless playground, catering to the desires of visiting Chinese gamblers and tourists who can openly purchase and consume illegal wildlife products and parts, including those of endangered tigers. There is not even a pretence of enforcement. Sellers and buyers are free to trade a host of endangered species products, including tigers, leopards, elephants, rhinos, pangolins, helmeted hornbills, snakes and bears, poached from Asia and Africa and smuggled to this small haven for wildlife crime. [It is] largely catering to growing numbers of Chinese visitors.”

Ammann began exploring the jungle regions of Southeast Asia while visiting his brother, who ran a hotel in Bangkok. He discovered the village of Mong La in Boko Province, the last Burmese outpost before China. “That was 40 years ago,” he says wistfully. “Today, it’s another sordid casino town thriving on drugs and prostitution, but then it was beautiful. I made contacts, went on expeditions, met hill tribes.”

On return visits, he realised things were changing fast and he began to document them. Wildlife trading was becoming an issue and he used his connections to probe it, first with questions and later with sophisticated button cameras and secret recordings.

“Because of my economic background [he worked in hotel finance], I was fascinated by the changing dynamic from sleepy hill station to illicit marketplace and conduit into China,” he says. “I was able to track changes in the area and thought I could make a contribution to conservation by letting the world know. It became something of an obsession.”

Those changes were to be devastating for elephants, rhinos, pangolins, tigers, bears and many creatures interesting to Oriental taste, superstition and aesthetics. In the uncontrolled, drug-saturated Golden Triangle, the illicit was profitable and law the prerogative of anyone wealthy enough to arm and command unscrupulous men. The area was to become, alongside the trafficking of narcotics and humans, China’s illegal wildlife supermarket. Ammann tried to get information out about what was going on. Nobody seemed interested. The area was a blank on the media map.

The transformation of Mong La became a model for the establishment of lawless outposts across the region catering for Chinese customers in search of products and pleasures forbidden in their country. Over the Burmese border in Laos, a Chinese company acquired a 99-year lease on 10,000 hectares of riverside jungle and built Kings Romans Casino, giving the government a 20% stake. Around 3,000 hectares have been declared a ‘special economic zone’ – essentially a private fiefdom. Clocks there run in Beijing time, trade is done in Chinese currency and businesses are Chinese-owned.

These casino towns make their own rules. Sellers and buyers are free to trade endangered species, while governments within the Golden Triangle curb any potential law enforcement. According to the EIA report, “the blatant illegal wildlife trade by Chinese companies in this part of Laos should be a national embarrassment and yet it appears to enjoy high-level political support from the Laos Government, blocking any potential law enforcement.”

Other developments include a private landing dock for boats, a hotel, massage parlours, museums, gardens, a temple, banquet halls, an animal enclosure, a shooting range and a large banana plantation. In these surrounds, and with de facto immunity from any known law, the illegal wildlife trade is booming.

Ammann acknowledges the value of reports such as Sin City and the integrity of the EIA but tells me they don’t go deep enough.

“You can’t find out about these networks like conservation NGOs do – by going around with a notebook logging items. You have to infiltrate,” he says, hunching over his coffee and looking the part. “That means buying from sellers – and I do that. The moment money changes hands, it becomes much easier. You get the information you wouldn’t get by just snooping around. So, I’m pushing the envelope – which most NGOs have a problem with.

“I send in my guys as bogus sellers of rhino horn. They show photographs and say: ‘We can get access to this. How much would you offer?’ In contraband investigation, that’s pretty common, but in the wildlife trade, few people are willing to go to that extent. If I give NGOs this data, they say they need to verify it. But they’re not prepared to use my methods, so how can they do that?”

Ammann’s methods of tracing networks through secret recordings and a bogus website he set up have paid off. He has traced the circuitous smuggling routes out of Africa and tracked down crooked officials and countless bogus export/import permits supposedly verified by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

He found that the wildlife trade in China is dominated by a handful of key players behind container imports. They have the infrastructure in Africa to get the containers loaded and shipped. They work with retailers, sending cell phone pictures ahead, signalling, say, 20 rhino horns on the way. They’ve operated with port authorities and key dealers for many years.

In 2008, China legally bought 66 tonnes of ivory from Africa in a CITES-sanctioned sale and built the world’s largest ivory-carving factory. It had listed ivory carving as an Intangible Cultural Heritage two years before that.

According to a report, Out of Africa, by C4ADS and the Born Free Foundation, China presently has 37 registered (and countless unregistered) carving factories and 145 retail outlets. A survey of the outlets found that most ivory items had no identity cards, meaning their source was illegal. In 2013, a contraband seizure in Guangzhou included 1,913 tusks – meaning almost one thousand dead elephants.

A 2002 document sourced by the EIA includes a Chinese official reporting the loss of 99 tonnes of ivory from government stockpiles – greater than the amount procured in the 2008 one-off sale. An NGO report in 2013 estimated that 70% of the ivory circulating in China was illicit and that 57% of licensed ivory facilities were laundering illegal ivory.

“I’m not sure to what extent China’s enforcement activity is real,” says Ammann. “It’s mostly for Western consumption. They sacrifice a shipment every now and then, and that’s probably part of the plan. Maybe they give the container back to the dealer after six months.

“If traders get a tipoff that the Chinese government is curbing the sale of ivory in China, they send the message down the line saying shift your ivory somewhere else. Laos, Burma, Vietnam. That’s where some of the big dealers have set up their operations, places like Kings Romans. It just means the conduit routes to China are shifting. Sales in China may be going down, but they’re going through the roof just over the border.

“Hong Kong is now coming under pressure, so dealers no longer see it as the future of rhino horn or ivory trade. They’re looking for new outlets in the Golden Triangle, Luang Prabang and Vientiane in Laos and in Vietnam. And if you put pressure on those countries, it will probably move to Cambodia.”

The truth is that the demand for wild animals, alive or dead, remains high, which is not good news for Africa’s animals. “Wildlife traders are running circles around us,” says Ammann, glancing at his watch because he has another appointment. “They’re fooling us, and most of them are Asian. And most of the NGOs – EIA is the exception – have operations in China or Thailand or whatever, so they can’t rock the boat too much. For an NGO, being banned from a region is a big problem. They can be the good cop but can’t afford to play the bad cop. I can afford to be that cop. The problem is getting the information out. Where and how can it make a difference?”

The only hope for elephants and rhinos and other creatures, he says, is if the risk factor is ratcheted up with some of the lynchpins ending up in jail. Hit the supply chains.

“If the world really became serious about enforcement instead of becoming serious about talking about enforcement, it would be a major step in the right direction. But it will only come on the back of face loss. We have to name and shame. But for myself, I want to be able to look at myself in the mirror in the morning. So I keep telling the facts and truth as I see them, knowing fully well that I will not win any popularity contests.”

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()