REDEFINE YOUR NOTION OF WILDERNESS

‘What’s great about the ocean is that you swim a hundred and fifty meters from the shore, and you feel vulnerable – you are in the wilderness,’ says Craig Foster. Feeling vulnerable is something most modern humans try to avoid, but it would have been a regular part of our ancestors’ lives, and it draws Craig into the cold waters of South Africa’s False Bay. He has been exploring these waters every day for four years, discovering previously unknown species and inspiring scientists and children alike to reconnect with the wild.

The Sea Change Project he is developing is multidimensional, involving film, photography and storytelling in live presentations, mobile exhibitions, and an expansive website. ‘The basis of it is that when you immerse in nature as deeply as you can, there’s this sea change – or transformation – that takes place because we are basically aligning ourselves with our original design,’ says Craig. ‘All those neural networks in the brain start functioning – all those things that activate primal joy. The water is a more extreme environment than land. You are inside water.’

By immersing yourself in nature you activate primal joy

I felt vulnerable, just sticking my toe in the cold water. Craig invited me to join him, his young son Tom and Ross Frylinck for a dive in False Bay. Ross is the director of surf lifestyle website Wavescape and a writer and director for Sea Change.

A prerequisite to diving with Craig is not wearing a wetsuit. ‘I want to get into the mind of Stone Age Man. I want to see how they saw things when they hunted in the ocean.’

We jumped from the rocks, and, before I could surface and take my first shaky breath, Craig, Tom, and Ross were swimming to the edge of the Kelp Forest. Soon they were motioning for me to join them, ‘Stingray! Come and see this.’ But I couldn’t pry myself from the shallows where I struggled to breathe. I needed time to adjust to the cold, and when I got there, the stingray was gone. ‘It was huge, about four meters,’ said Craig happily, adding how unusual it was to see it here in the kelp. But I wasn’t disappointed because by swimming down in search of the stingray, I entered a world where I felt cold, vulnerable, and ecstatic.

Later, from the shore, Ros and Tom noticed a great white shark taking some prey some 50 meters off the kelp line. Craig realised this was why the stingray and some seals had come into the kelp, but because the water was clear we were not threatened by the shark as it does not identify humans as prey.

MASTERS OF WILDERNESS SURVIVAL

Foster, at a young age, was obsessed with the intertidal zone. He grew up along the coast in his family’s wooden bungalow, the lower level of which was below the high watermark. ‘In the big Atlantic storms, we had to board up the windows. The bottom of the house would often fill up with seawater.’

He and his brother were walking and diving along the coast by age three. In those days, there was no supervision. There was no iPad. They would spend whole days exploring the tidal pools and kelp forests. Their food was what the ocean provided, and they could survive like that by the age of six.

Sea Change reawakens the first African coastal family

This deeply influenced Craig; as an adult, he wanted to learn more. But no more coastal hunters were left around False Bay, and no mentors to guide the brothers through the finer arts of wilderness survival. ‘That’s what drew me away from the ocean to the Kalahari, where the San are the masters of wilderness survival.’ The Foster brothers spent three years filming their celebrated documentary The Great Dance: A Hunter’s Story there.

After a long series of films, Craig was burnt out. His way to recovery was to return to the ocean, so he moved to Simons Town, where he swam daily, gradually recovering and reconnecting with the wild in False Bay.

During that time, Canadian anthropologist and filmmaker Niobe Thompson, who had seen The Great Dance, and was creating a human origins series, approached Craig and asked him to recreate and film the first African coastal family. It turned out to be one of the foundations for the Sea Change Project.

STONE AGE MAN’S

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE OCEAN

Craig was determined to be completely faithful in recreating a 100,000-year-old Stone Age family and collaborated with archaeologist Christopher Henshilwood and ethno-ecologist Tony Cunningham. ‘I got a real feeling for original existence along the coast – a time when Homo sapiens were innovating at an incredible level.’

He describes evidence of rock art discovered by Henshilwood in Blombos cave near Stillbaai dated to 77,000 years ago, which makes it about 40,000 years older than the oldest art in Europe. Also found at Blombos is an abalone shell containing a mixture of red ochre, bone and charcoal. It is estimated to be about 100,000 years old, making it the oldest human-made container ever found and the world’s oldest chemical mixture for adornment. He believes that the carpet of low-tide kelp would have been the environment where we first learned how to wade, swim and eventually dive by following rich food sources, like abalone and crayfish, deeper into the ocean. ‘People might shoot me down, but I think this time was when humans lived at their highest potential.’

Thompson expected him to work on the project for six weeks, but Craig spent eight months creating the family with local fishing people who had a strong connection with the ocean.

Donovan van der Heyden is one of them. A traditional fisherman and community leader, Donovan is active in establishing the rights of traditional fishermen. As resources dwindle due to commercial fishing and poaching, his community is under pressure. ‘Youngsters are being lured into poaching by the quick money,’ he says. ‘I want to be able to educate them about the importance of conserving wildlife and remind them of our spiritual connection with the ocean.’ In working with Craig in recreating our roots, Donovan has rekindled his connection with the ocean and feels the Sea Change Project can be integral in his quest to teach the youth about their marine heritage and how to conserve it.

THE POWER OF COLD

‘There’s a strange thing that happens to our bodies when it comes to cold water – with immersion and holding our breath. Everything is fast-tracked,’ says Craig.

I recognised this as I swam through the kelp forest, pulling myself down on long kelp stems to reach the rocky floor, holding my breath for longer as I dived deeper. The reward was a clarity of vision, a sharpening of the senses. While my inner core kept itself warm, my skin took on the temperature of the water. After a short while, I did not feel cold; I just felt like I was part of it. We swam for about 45 minutes, flying through the Kelp forest between myriad fish, diving down to greet octopus and crabs and anemones and sea urchins of every colour imaginable.

Tom hitches a ride on his father’s shoulders. ©Craig Foster/Sea Change Project

When you become cold-adapted you feel more human

‘We are supposed to be cold-adapted as humans, but today we are programmed to keep warm – put on our jackets when there’s a chill – but it’s not natural. When you become cold-adapted, your hormonal system changes; your immune system strengthens. There’s a transformation on many levels. We don’t step back into the original design, but some of that criterion is fulfilled. Ultimately you feel more human,’ says Craig. ‘Some of the kids involved in this project have gone home to do ice baths, and their parents ban them from doing it. So they sneak cold showers. It’s hard to stay cold in our mad world!’

One of those kids is 12-year-old Epiphany Stransham-Ford. Her father went diving with Craig and afterwards encouraged Epiphany to join them. ‘My dad thought it was the most incredible experience, and he knew how much I loved animals, so he suggested I go along too,’ she explains. Since then, Epiphany has become one of the ambassadors of Sea Change.

‘I was never interested in marine life before. I wanted to be a wildlife veterinarian and work in the bush. But when I went diving with Craig, that changed,’ she says. ‘My first dive wasn’t great, but on my second dive, I opened up. I totally relaxed and began appreciating the beauty of the surroundings.’

By her own initiative, Epiphany has been working with the Sea Change Project and the conservation organisation Mission Blue, headed up by renowned Ocean Explorer Dr Sylvia Earle. Mission Blue has designated Hope Spots along the globe’s shores – places critical to the ocean’s health – and False Bay is one of them. Through her learning and ocean experience, Epiphany now talks at schools where she inspires kids to conserve the ocean.

NEVER BEFORE SEEN

Aided by his heightened senses and the frequency with which he explores the water near his home, Craig started noticing creatures not recorded in guidebooks. He reached out to Emeritus Professor Charles Griffiths to help identify them. Griffiths headed up the marine biology team at the University of Cape Town for 25 years and is one of the authors of Two Oceans, A Guide to Marine Life of Southern Africa. He has also become a mentor to Craig, who holds him in the highest esteem for the valuable expertise and time he has given to the project.

‘Craig has a particular style of photography, and he’s photographed some remarkable things,’ says Griffiths. ‘What Craig does is valuable because he lives on the shore and often dives in the same places. For example, if Craig sees a snail laying a group of eggs and goes back every day to observe and document it, we can learn an extraordinary amount from it. As scientists, we don’t often have the time and resources to do that.’

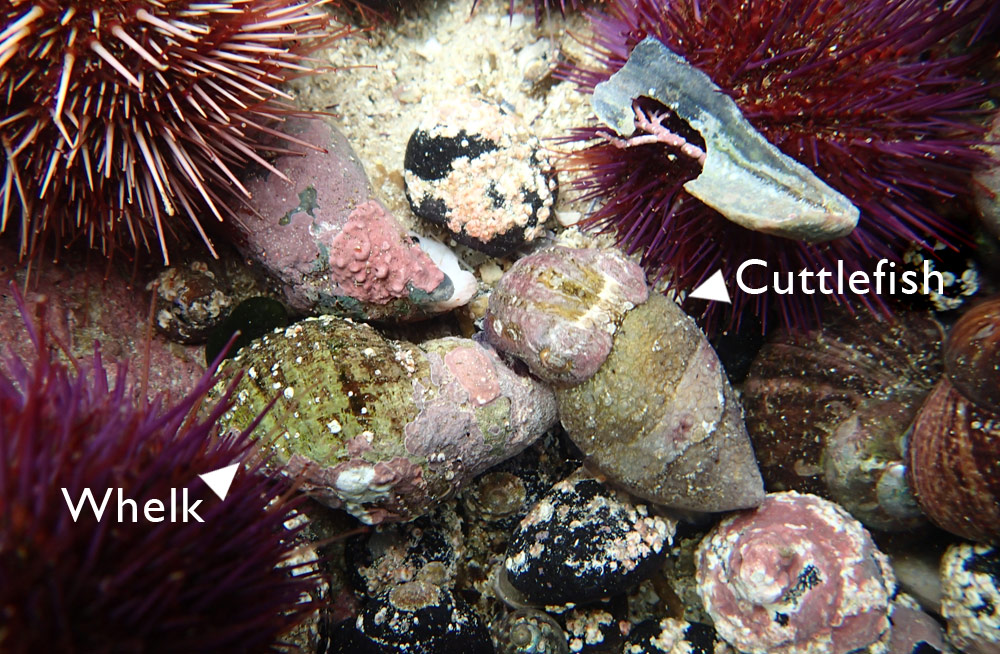

Middle: The small cuttlefish the team are studying due to its never before seen behaviour, illustrated below.

Bottom: When the cuttlefish is threatened by predators, it can change colour, texture and shape to mimic a whelk.

©Craig Foster/Sea Change Project

One of Craig’s most remarkable observations is the never before seen behaviour of cuttlefish, which Griffiths and marine biology student Jannes Landschoff are studying. Its behaviour is unique and has not been documented until now.

To evade predators, the cuttlefish adapts its skin colour, texture and body shape to mimic other creatures, such as a whelk (sea snail), which it lies beside and mirrors, as seen in the image above. When under threat, instead of swimming away and drawing attention to itself, the cuttlefish can also use its tentacles to mimic the legs of a hermit crab, fooling predators by slowly walking away like a crab.

Craig joins Charles and Jannes to explore and share information as often as possible. Jannes, who is originally from the north of Germany, is, as he says, naturally cold-adapted.

‘The marine life on the coast here is so diverse,’ says Jannes. ‘Bays are unusual along this part of Africa’s coast, and the life in False Bay is so rich because it is well sheltered. It’s also between two oceans where you have warm and cold currents meet.’

Much of the sea life has been wiped out on the coasts of Europe, so for Jannes, it is thrilling to study here, and Craig enhances that experience for him. ‘Craig is so in tune with nature. It gives me a completely different approach. When I first met Craig, I thought he was either a genius or completely mad. I came to realise he is both,’ laughs Jannes. ‘I don’t think he is fully aware of his amazing work, and I don’t know anybody with a similar approach. The spiritual philosophy behind what Craig does makes it translatable to an audience. I’m not religious; I guess if I have spirituality, it has always been science, and Craig’s philosophy is something I can tune into.’

©Craig Foster/Sea Change Project

THE ROPES TO GOD

‘There are many more animals in the water than there are on land,’ says Craig. ‘Big animals are approaching you. On land, that doesn’t happen because they’ve had millions of years to become afraid of us. But we never dominated water, so the animals aren’t scared of you. They often make contact if they don’t sense you are a threat. That’s why you’ve got to relax in the water.’

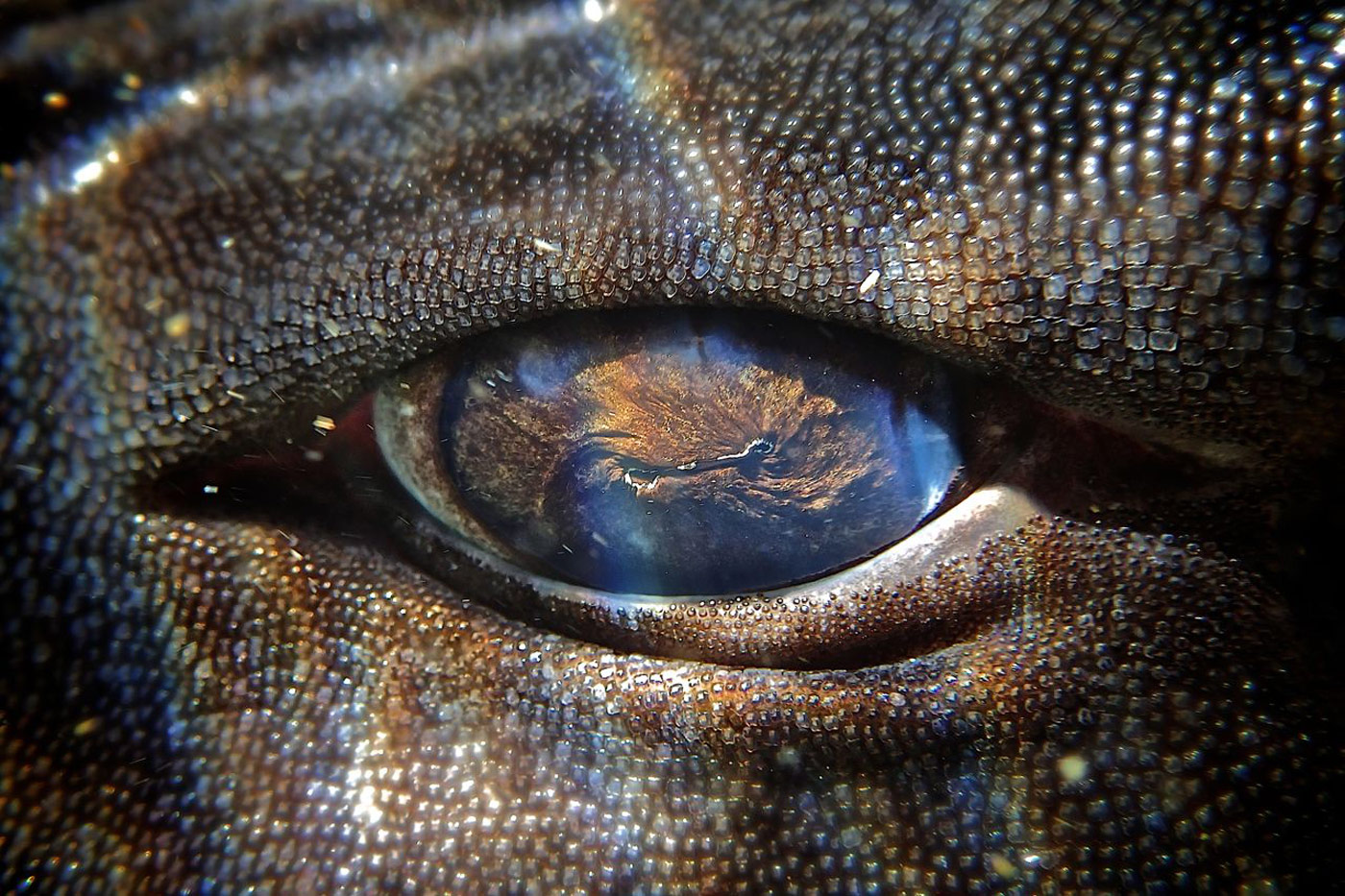

I couldn’t relax when Ross handed me a small cat shark. It was gently ensconced in his hands as he swam up to me, but I was wary so as he handed it to me, it became catatonic, coiling in on itself suddenly and sinking to the ocean floor. Once it sensed no further threat, it uncoiled and swam off again. I definitely needed to relax. And I decided the best way to do that was to give myself to the water.

‘In that cold water, it was a feeling of warmth’

Craig introduced me to a crab that, after resting for a while on my hands where we could study each other, climbed along my arm and seated itself there as I swam along like a steward. It made me feel relaxed, and welcome. It would have stayed there for longer if I hadn’t returned it to the ocean floor. Soon after, Craig brought an octopus up to greet me. He put it into my open hands, where it coiled its tentacles gently around my arms and sat facing me. I watched its bulbous head expand with every breath, its skin changing colour from dark purple to light pink, its eyes looking into mine.

‘It can happen anywhere – you can make these relationships with nature on land and in water,’ says Craig. ‘When you give an animal your attention, it can feel it. Imagine doing that with hundreds of species the whole time – a reciprocal bonding between you and nature. This is what the San call the ropes to God. It’s part of our psychological makeup. Imagine just cutting that off.’

The octopus and I stared at each other for a while. It’s the closest I have ever felt to nature. In that cold water, it was a feeling of warmth. Then it calmly swam away, and I followed it for a while like it was tugging me along.

Contributor

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, and drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, and drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()