South Africa’s commercial captive lion breeding industry, a sector that has grown to encompass roughly 350 facilities holding nearly 8,000 lions, has long been a subject of debate. While proponents have claimed a role in conservation, new research presents a sobering challenge to this narrative, questioning whether the industry is in fact harming wild lion populations

South Africa’s commercial captive lion breeding industry, a sector that has grown to encompass roughly 350 facilities holding nearly 8,000 lions, has long been a subject of debate. While proponents have claimed a role in conservation, new research presents a sobering challenge to this narrative, questioning whether the industry is in fact harming wild lion populations

Over the past three decades, a contentious industry has quietly been established in South Africa, steadily growing louder and more robust as it gained popularity. In the face of threats to wild lion populations, captive-lion breeding claimed to contribute to conservation.

Many claim captive lion breeding can reduce the pressure on wild lion populations by supplementing commercial demand for lions, their parts and derivatives. But there is also an alternative effect: captive-lion breeding can increase the demand for lions and their body parts, which essentially threatens wild populations.

A group of researchers from Blood Lions and World Animal Protection is attempting to put the debate to rest. Their latest research, including a systematic review titled Reviewing evidence for the impact of lion farming in South Africa on African wild lion populations, published in the journal Animals, highlights the urgent need for a shift in policy.

The comprehensive study entailed the review of 126 peer-reviewed articles and 37 public reports published between 2008 and 2023, in efforts to assess whether commercial captive lion breeding helps reduce pressure on wild lion populations.

The scale of the industry

South Africa’s commercial lion breeding industry has seen rapid growth since the 1990s, expanding to an estimated 7,838 captive lions, along with thousands of other big cats, across 342 commercial facilities for tourism, hunting and trade. To put this into perspective, in 2021, Four Paws estimated that the number of farmed lions in South Africa was four to five times larger than that of wild lions.

The captive lion industry primarily thrives on tourist entertainment like cub petting and walking with lions, as well as the commercial trade of lion body parts and derivatives.

Investigating captive lion conservation claims

The central question investigated by the researchers was whether this commercial captive lion breeding provides a sustainable solution to reduce pressure on wild lion populations. Their comprehensive review yielded a concerning conclusion: there is currently no scientific evidence to substantiate the industry’s claims that commercial captive lion breeding protects wild lion populations.

On the contrary, the findings suggest that it may be driving demand for lion parts with potentially damaging consequences for the species in the wild. Dr. Angie Elwin, a contributing researcher and Head of Research at World Animal Protection, says, “Our review finds no clear evidence that South Africa’s captive lion breeding industry benefits wild lion populations.” Elwin continues, “…it could be doing harm by fuelling demand for lion parts. Given the precarious status of lions globally, any claims of conservation value should be treated with extreme caution. Lessons from tiger farming show that legal trade from captive animals has failed to protect wild populations and may even accelerate their decline. We risk repeating the same mistake with lions.”

The evidence against captive lion breeding

The study evaluated the evidence against five key criteria to determine the potential benefits and threats of lion farming in a conservation context. Here’s what they found:

- Cost-efficiency: Although captive hunts are generally cheaper than wild hunts, direct comparisons of overall profitability between wild and captive-sourced lion products are scarce. However, captive facilities boost profitability through diverse income streams, including selective breeding for rare traits like white lions and hosting paying international volunteers.

- Genetic maintenance of captive populations: A significant knowledge gap exists regarding the genetic health and diversity of captive lion populations, primarily due to a lack of official records and comprehensive genetic analysis. While there’s limited evidence of wild lions being taken to stock captive facilities, the absence of a reliably maintained studbook system raises concerns.

- Protection from criminal activity: The study revealed inadequate protection for wild populations from criminal activity linked to lion farm facilities. Evidence, though sporadic and often anecdotal, points to potential laundering of wild-sourced lion parts through captive facilities and a patchwork of inconsistent legislation across authorities. The direct link between lion farming and the poaching of wild lions remains largely unquantified.

- Consumer preferences: While some captive-bred lion products, like those for trophy hunting, might be preferred for specific traits or guaranteed kills, the research indicates mixed preferences, with no clear evidence that farmed lion parts consistently substitute for wild ones. For traditional medicine, consumers often don’t distinguish between wild and captive sources, and lion bones are even passed off as tiger bones.

- Market demand: The review suggests that rather than simply meeting existing demand, commercial captive breeding may actually be stimulating new demand. This includes the emergence of new markets, such as interactive tourism experiences (like cub petting) that create additional demand for breeding lions for revenue. Rising wholesale values for lion skeletons also point to increasing demand. The review notes that lion skeletons have historically been exported to East and Southeast Asia for traditional medicine markets; although the legal skeleton trade is currently halted following a 2019 court judgment, other legal and illegal channels persist, including trophies and live exports.

Current state of affairs

Importantly, the researchers note that South Africa’s wild lion populations are considered stable, due to intensive management on large protected areas and many smaller reserves. But continent-wide, lions remain Vulnerable and declining, with targeted poaching for body parts rising as an emerging threat.

One of the most damning results from the study was that researchers found insufficient data to effectively evaluate any purported conservation benefits of captive lion breeding. Instead, their analysis identified several “red flags” suggesting that lion farming could accelerate and facilitate commercial demand for lions and their body parts, potentially jeopardising wild populations. This contrasts with the 2018 assessment by the Scientific Authority of South Africa, which previously concluded that the export of captive-bred lion products did not negatively impact wild lion populations.

In July this year, Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment, Dr Dion George, announced the imminent publiction of the Lion Prohibition Notice, which will prohibit the establishment of new captive lion facilities for commercial purposes. However, there is still a long way to go before a full prohibition of the commercial breeding and keeping of captive lions.

The driving force: Demand for lion parts

The review highlighted that while trophy hunting of captive lions has seen a decrease following events like the US boycott after Cecil the lion’s shooting, a parallel surge in demand for lion bones from Southeast Asia has taken its place. These bones are often passed off as tiger bones for use in traditional Chinese medicine products like tiger cake, tiger wine, and other “tiger” derivatives. The staggering profit margins, with a 60-fold increase between the South African skeleton sale value and the end consumer price, incentivise this trade.

The research identified several “red flags”, suggesting that captive lion breeding may:

- Accelerate and facilitate commercial demand for lions and their body parts;

- Increase opportunities for laundering poached wildlife through legal commercial trade; and

- Operate within a patchwork of contrasting legislation across various authorities, creating legal loopholes and making fraud difficult to monitor

Beyond conservation: Animal welfare and public health risks in the captive lion industry

The concerns extend far beyond the conservation impact on wild lions. The High-Level Panel report, released as a part of the Draft policy position on the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of elephant, lion, leopard and rhinoceros in 2021, led to the government’s decision to ultimately close the industry. These findings outlined that the captive lion breeding industry:

- Damages South Africa’s eco-tourism and conservation reputations;

- Lacks necessary transformation;

- Is widely accused of animal welfare neglect and abuse; and

- Poses public health concerns, including the risk of diseases like tuberculosis being transported through wildlife products.

A call for urgent action

The research underscores the urgent need for a shift in policy. The researchers and contributing organisations are calling on the South African government to take critical next steps based on these findings. Dr. Louise de Waal, Director of Blood Lions, emphasises the need for global caution: “We need to err on the side of caution globally, but in particular in lion range states, to refrain from facilitating further emergence of commercial captive predator breeding and trade.”

She highlights that this is especially relevant given the increased wildlife trafficking opportunities between Africa and Southeast Asia, partly fuelled by the expansion of initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (a global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the government of China in 2013).

The new research adds significant weight to these arguments, urging the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment to take critical next steps: to impose an immediate moratorium on the breeding of lions in captivity and to develop a structured and time-bound phase-out plan for the broader commercial predator industry.

While wild lion populations in South Africa are currently considered unchanging, these research findings highlight the significant and potentially detrimental compounding effects on already vulnerable lion populations and other large felid species across their ranges. The industry’s lack of transparency, coupled with identified knowledge gaps in consumer preferences, supply-demand dynamics, economic comparisons, genetics, and the extent of illegal activities, further strengthens the call for a definitive end to commercial captive lion breeding.

Reference

Green, J., Elwin, A., Jakins, C., Klarmann, S.-E., de Waal, L., Pinkess, M., & D’Cruze, N. (2025). Reviewing Evidence for the Impact of Lion Farming in South Africa on African Wild Lion Populations. Animals, 15(15), 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15152316

Further reading

- A new survey sheds light on the state of the lion population in the north of Kruger, revealing trends that could shape future conservation efforts. Read more about Kruger’s lion population here

- Africa’s lions are disappearing. New research shows that lion populations across the continent have declined by 75% in just five decades

- For the best chance of seeing lions in the wild, head to one of Africa’s top lion hotspots – as recommended by AG safari experts

- Does lion pride behaviour change between fenced & open systems? Researchers monitoring lions in Kruger, Pilanesberg & more aim to find out

What started as a stressful discovery evolved into one of my best wild dog sightings ever.

What started as a stressful discovery evolved into one of my best wild dog sightings ever.

Dr Paul Funston is a leading African conservationist with over 30 years of experience dedicated to the protection of lions. He holds a PhD in Zoology from the University of Pretoria, where he studied lion population dynamics and behaviour in Kruger National Park. Paul is a recognised authority on predator-prey relationships, habitat connectivity, and sustainable lion conservation.

Dr Paul Funston is a leading African conservationist with over 30 years of experience dedicated to the protection of lions. He holds a PhD in Zoology from the University of Pretoria, where he studied lion population dynamics and behaviour in Kruger National Park. Paul is a recognised authority on predator-prey relationships, habitat connectivity, and sustainable lion conservation.

Blondie, a well-known, collared pride male lion in Zimbabwe’s Hwange area, has been trophy hunted after being lured into a hunting area with bait – leaving behind 10 cubs

Blondie, a well-known, collared pride male lion in Zimbabwe’s Hwange area, has been trophy hunted after being lured into a hunting area with bait – leaving behind 10 cubs

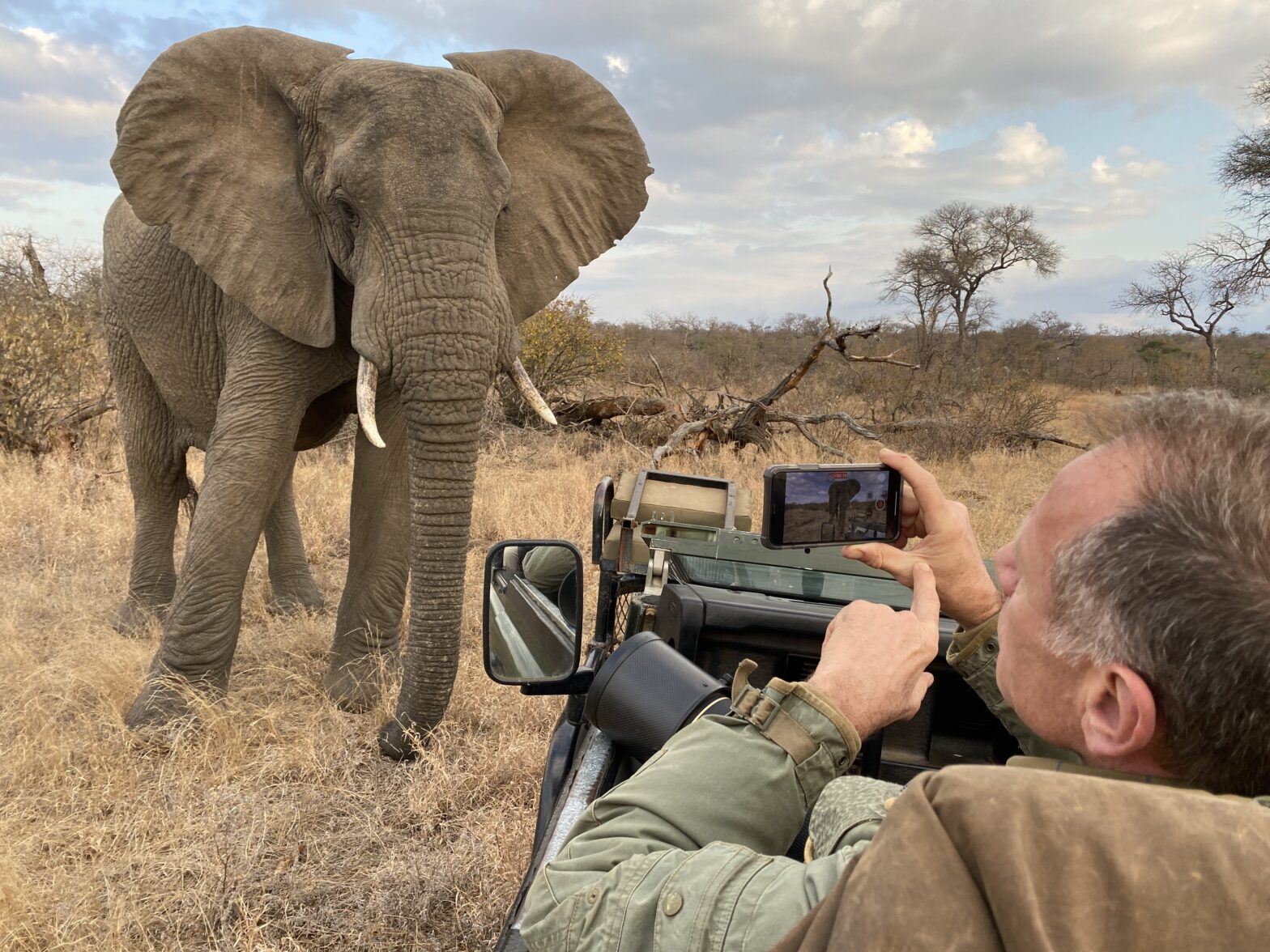

As social media rewards spectacle over substance, some private guides are prioritising viral content at the expense of ethics, safety, and the very animals they claim to champion. Drawing on firsthand accounts from across Africa and India, Adam Bannister explores the troubling rise of performative guiding – and makes a compelling call for a return to integrity, collaboration, and true connection with the wild

As social media rewards spectacle over substance, some private guides are prioritising viral content at the expense of ethics, safety, and the very animals they claim to champion. Drawing on firsthand accounts from across Africa and India, Adam Bannister explores the troubling rise of performative guiding – and makes a compelling call for a return to integrity, collaboration, and true connection with the wild

Adam Bannister is a South African-trained biologist, safari guide, author and storyteller who has spent nearly two decades immersed in some of the world’s most iconic wild places, from the Sabi Sands and Maasai Mara to the deserts of Rajasthan and the forests of Rwanda and Peru. With a passion for training guides,

Adam Bannister is a South African-trained biologist, safari guide, author and storyteller who has spent nearly two decades immersed in some of the world’s most iconic wild places, from the Sabi Sands and Maasai Mara to the deserts of Rajasthan and the forests of Rwanda and Peru. With a passion for training guides,

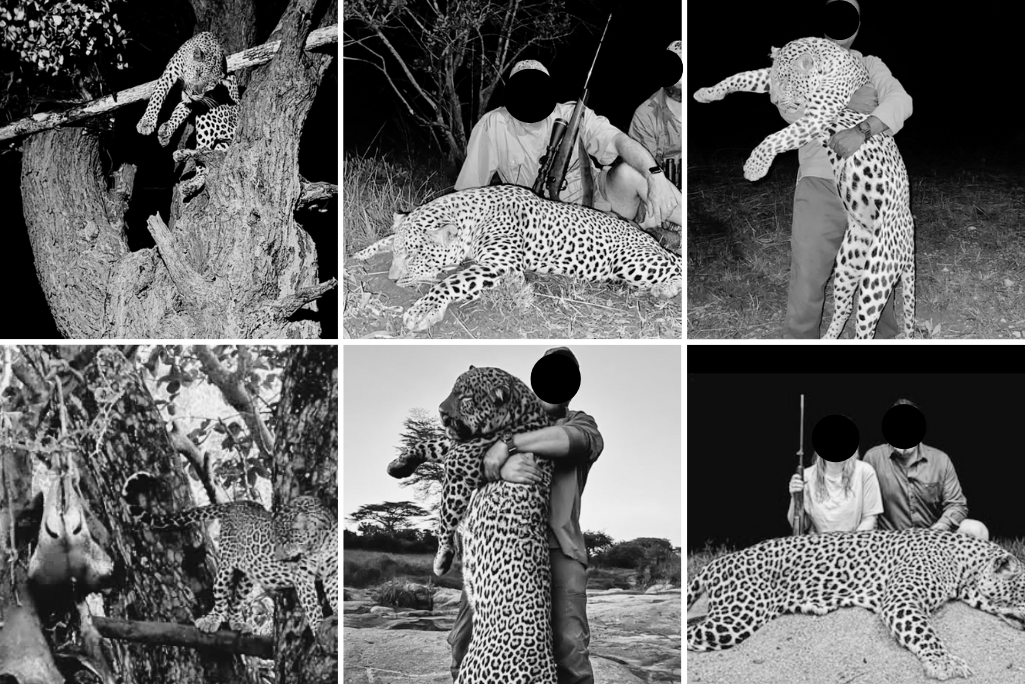

Leopards are Africa’s most enigmatic big cats: silent, solitary, and vanishing fast. Behind their fading presence lies a thriving global industry built on prestige, profit, and skull measurements. According to a

Leopards are Africa’s most enigmatic big cats: silent, solitary, and vanishing fast. Behind their fading presence lies a thriving global industry built on prestige, profit, and skull measurements. According to a

Born in Kassel, Germany, Christina is a clinical psychologist. In her spare time, she explores wild corners of Africa with a camera in hand. Her travels have taken her to South Africa, Kenya, Botswana, Namibia, Tanzania and Uganda. Wildlife photography is her mindfulness – a meditative exercise in patience, observation, and reverence for the natural world.

Born in Kassel, Germany, Christina is a clinical psychologist. In her spare time, she explores wild corners of Africa with a camera in hand. Her travels have taken her to South Africa, Kenya, Botswana, Namibia, Tanzania and Uganda. Wildlife photography is her mindfulness – a meditative exercise in patience, observation, and reverence for the natural world.

A professional wildlife photographer and guide from Johannesburg, Ernest’s passion for wildlife began during childhood visits to Kruger. Fresh out of high school in 2010, he sacrificed three electric guitars and an amplifier for his first starter-bundle camera. Thereafter, he spent years honing his skills at Walter Sisulu Botanical Gardens, photographing the resident Verraux’s “eagles.”

A professional wildlife photographer and guide from Johannesburg, Ernest’s passion for wildlife began during childhood visits to Kruger. Fresh out of high school in 2010, he sacrificed three electric guitars and an amplifier for his first starter-bundle camera. Thereafter, he spent years honing his skills at Walter Sisulu Botanical Gardens, photographing the resident Verraux’s “eagles.”

Based in San Diego, California, Mary’s roots in theatrical design and visual storytelling give her wildlife photography a narrative depth. Mary has photographed wildlife across the globe, from Africa’s golden plains to the icy stillness of the Arctic. But it’s the quiet moments – glances, gestures, pauses – that captivate her. Mary’s work honours the untamed and tells stories of connection. When not in the field, she’s home editing photos with coffee and a cat by her side.

Based in San Diego, California, Mary’s roots in theatrical design and visual storytelling give her wildlife photography a narrative depth. Mary has photographed wildlife across the globe, from Africa’s golden plains to the icy stillness of the Arctic. But it’s the quiet moments – glances, gestures, pauses – that captivate her. Mary’s work honours the untamed and tells stories of connection. When not in the field, she’s home editing photos with coffee and a cat by her side.