Our 2021 Photographer of the Year has come to a glorious finale as we present the best submissions. The winner and two runners-up will share the princely sum of USD 10 000 and join their partners and our CEO Simon Espley and his wife Lizz on the ultimate private safari in Botswana, where they’ll take more wonderful snaps of our wildlife, landscapes and fascinating, resilient people.

MESSAGE FROM OUR EDITOR-IN-CHIEF:

It has been a great joy and privilege to receive your entries each week, to see the vastly different perspectives of Africa. Over the desert sands, across the savannas, through the forests, under the ocean and from the mountain fastnesses, you have sent us images that inspired awe, wanderlust and a connection to wild places we so desperately need.

We have managed to pick a winner from 25,023 photographs of our magnificent continent (well, 99.9% celebrated Africa; a few entries celebrated motorcycles, house pets and body parts – but they do not feature here).

It is fashionable in competitions to lament how hard the judging process is. We must repeat the cliche because it was genuinely challenging to pick the winners.

We judge images on their ability to tell a story, evoke emotion and capture the essence of Africa. We also look at technical aspects of the photos – both in the capture and edit stages of creating an image. We are but human, and therefore the judging cannot be entirely objective – many entries may well succeed in other competitions.

To all who had the courage to enter, thank you from Africa Geographic and all our tribe who have enjoyed their vicarious connection to African wilderness through your efforts. We hope you’ll take part again next year. Entries open on 1 January 2022.

Finally, a massive thank you to our sponsors Hemmersbach Rhino Force and Natural Selection – this epic annual celebration would be so much the poorer without you.

Winner – Photographer of the Year 2021

A lion cub tries to nudge dad, but the male is grumpy. At the click of the shutter, a fly passes through the focus point and the pupil of the eye. The blunt teeth indicate an old male – but clearly, one still to be feared. Cubs always tread lightly around the males, weary of a swipe.

Judges’ comment

With one snap of the shutter, this image succeeds with so many of the criteria that make an excellent photograph. It is technically brilliant from the perspective of timing, anticipation and setting the camera perfectly for the predicted behaviour. The edit is also captivating – the colour and contrast create a mood that complement the lion’s palpable anger. Then, as with so many great wildlife shots, luck played a huge part as the fly just happened into frame at the right time.

About the photographer Hannes Lochner – Read more

Hannes Lochner is a renowned, award-winning wildlife photographer and has been taking pictures professionally since 2007. He has long been fascinated by the arid zones of Southern Africa, which of course, include the Kalahari. His name is now synonymous with the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park and the park’s leopards in particular.

Hannes Lochner is a renowned, award-winning wildlife photographer and has been taking pictures professionally since 2007. He has long been fascinated by the arid zones of Southern Africa, which of course, include the Kalahari. His name is now synonymous with the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park and the park’s leopards in particular.

Hannes was born in South Africa and knows the countries of Southern Africa exceptionally well. Since childhood, he has travelled to Namibia at least once a year and has a profound knowledge of that country and its photo spots.

He has published several, amazing books, two of which were entirely dedicated to the Kalahari. To realise these projects, he lived for six years in the Kalahari and invested hundreds of hours in photographing the magical landscape and fascinating wildlife. His new coffee table book, Planet Okavango, was published recently. Hannes spent two years completing it in Botswana.

Hannes is extraordinarily talented at image composition and the interplay of various light conditions. His pictures show the essence of the landscape and its animals while telling their stories. His passion for art ensures that his pictures stand out from the work of conventional wildlife photographers. His skills enable him to produce work that attracts great attention continuously. Hannes is also passionate about passing on his knowledge.

He has been awarded various international awards over the past few years.

Instagram: hannes_lochner

Website: www.hanneslochner.com

RUNNERS-UP

(in no specific order)

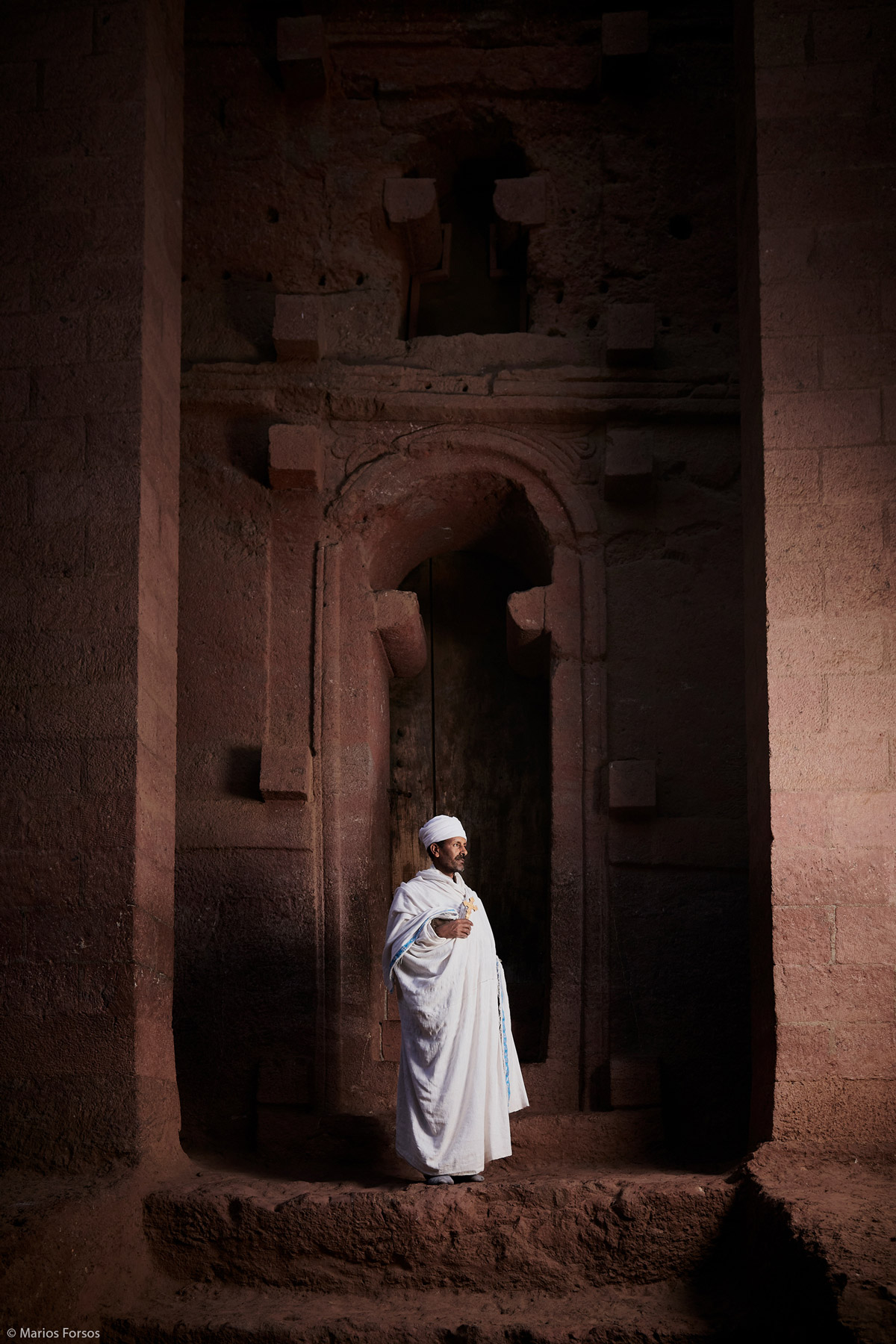

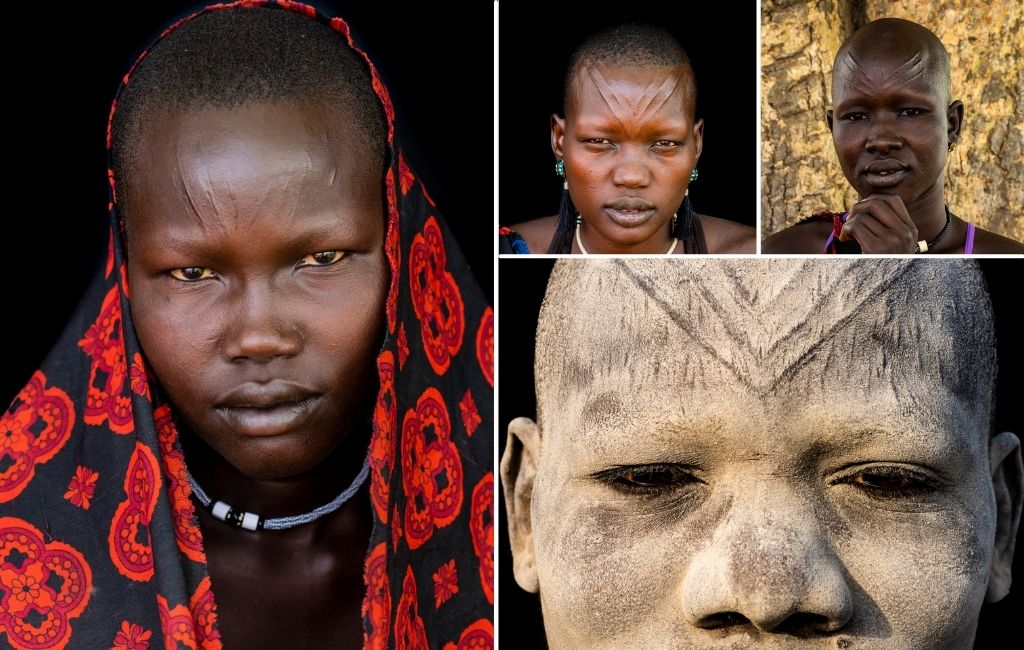

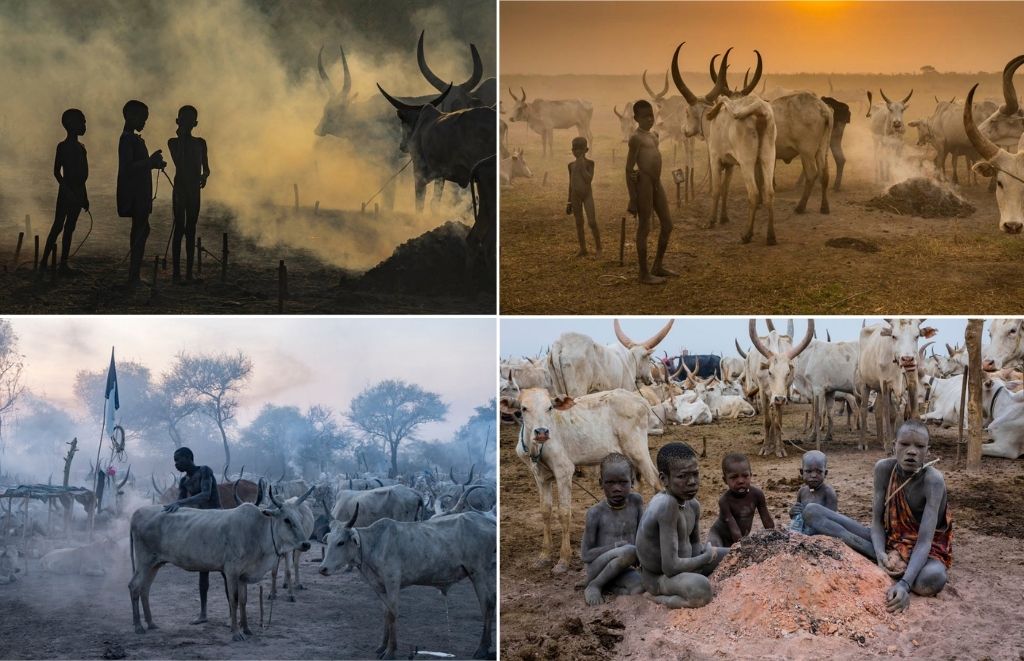

This photo was taken in a Mursi village in southern Ethiopia. Many people believe that photography in Africa is all about animals and landscapes. However, the people of this part of the world are actually more fascinating to me. Whether it is Ethiopia or Morocco, there is a great depth of culture and history.

On my way out of the village, I saw this woman holding an AK47, nursing her child. As I walked closer, it was the baby’s eyes that attracted my attention. He stared straight at me. I used body language to ask the mother if I could take a photo of her and her baby. She granted permission, and I started to use my wide-angle lens to focus solely on the baby boy. It felt like he was talking to me through the lens – I believe this is what photography is meant to do. I asked my guide for the reason the mother was holding the weapon and he answered that she was simply trying to show off that she has a husband who is a good warrior.

Judges’ comment

This is an exceptionally powerful image that is as incongruous as it is moving. It captures the hardship experienced by so many women in Africa while managing to express their strength and resiliance at the same time. Add the myriad gorgeous textures – warthog tusk, rifle stock, rope, bell, hair – and you have a cracking shot.

About the photographer Bob Chiu – Read more

Bob Chiu was born in Hong Kong and lives in Los Angeles, USA. He is a visual storyteller whose images from travel to street photography convey the beauty of various human cultures, emphasising human interactions. He aims to capture precious moments of unique human interaction in a rapidly changing world. He hopes his work can help make the world a smaller place by allowing people from different parts of the globe to know each other better.

Bob Chiu was born in Hong Kong and lives in Los Angeles, USA. He is a visual storyteller whose images from travel to street photography convey the beauty of various human cultures, emphasising human interactions. He aims to capture precious moments of unique human interaction in a rapidly changing world. He hopes his work can help make the world a smaller place by allowing people from different parts of the globe to know each other better.

Besides the United States and Canada, Bob has travelled to China, India, Ethiopia, Cuba, Iran, Morocco, Israel, Russia, Ecuador (Amazon Rainforest), the Balkans and other parts of Asia and Europe. In 2018 and 2019, he held exhibitions and talks at Leica India where he showcased his work on Ethiopia. His work was also part of the Leica Club International of Moscow’s exhibition in 2019.

His work, “The Land of Buddha”, was a finalist at the 2020 “Art of Building” annual competition of the Chartered Institute of Building in the UK.

Bob holds the following photography distinctions:

- Grand Master (GMPSA), Gold (GPSA) – Photographic Society of America PSA

- Associate (ARPS) & Licentiate (LRPS) – Royal Photographic Society RPS

- Excellent (EFIAP) – Federation Internationale de I’Art Photographique FIAP

- Certified Master (CMP) & Certified Excellence (CEP) – Professional Photographers International PPI

- Follow (FAPAS) – Association of Photographic Artists Singapore

- Follow (FPVS) – PhotoVivo Singapore

Instagram: bobchiu95

I found this white rhino mother and calf resting in the heat of the day and returned to a nearby waterhole just before sunset, hoping they might visit to drink. I realised that the dusty ground would create a dramatic effect if I shot into the sun and underexposed as the rhinos were walking past. So, having snatched a couple of shots of them drinking, I relocated to get a view of the route I expected them to take when they left. With lots of trees in the area, the rhinos would only be in the open for a few seconds, and if they left in a different direction, I wouldn’t get a single shot. Fortunately, the gamble paid off.

Instead of focusing on the negative aspects of rhino poaching, I wanted my picture to convey a sense of hope – a new beginning almost – as if these were the first rhinos being forged in the fires of creation. The effect of the backlit dust, creating a blurred shadow image, added to the ethereal effect. Botswana’s battle against poaching has been well-documented. Sadly, the health of the rhino reintroduction programme has been hit hard, particularly in the last year when the lack of tourists has left conservation areas unguarded. For me, the decreasing rhino numbers give this image even more resonance. It is now vital that the remaining rhinos in Botswana are conserved for future generations.

Judges’ comment

This is the sort of image in which you see something new every time you look at it. It’s a clever capture that shows the photographer has a great appreciation of light and how his camera interacts with it. It conjures a feeling of awe and positivity with regard to rhinos.

About the photographer James Gifford – Read more

Based in Botswana for the last 15 years, James Gifford is a multi-award-winning photographer, writer and videographer, with two published books and numerous magazine credits to his name. In between guiding specialist photographic safaris and creating marketing content for safari companies, he takes every opportunity to get into the bush to create images that can influence how we think about the world and conserve the bounty of wildlife that is still left on our planet.

Based in Botswana for the last 15 years, James Gifford is a multi-award-winning photographer, writer and videographer, with two published books and numerous magazine credits to his name. In between guiding specialist photographic safaris and creating marketing content for safari companies, he takes every opportunity to get into the bush to create images that can influence how we think about the world and conserve the bounty of wildlife that is still left on our planet.

Instagram: jamesgiff

Website: https://www.jamesgifford.co.uk/Safaris

HIGHLY-COMMENDED

(in no specific order)

I titled this image ‘The Murderous Pharaoh’ because of the nature of the cheetah’s pose and the blood dripping down the chin, very much resembling a pharaoh’s beard. The brutality of a cheetah kill often goes unnoticed. The violence involved and the fierceness displayed left me at a loss for words.

Judges’ comment

This image manages to be both brutal and somehow darkly amusing at the same time. The viscera dripping from the cheetah’s face evokes the savagery of a hunt on the plains but his expression indicates a slight dissatisfaction with the mess he’s made.

About the photographer Aditya Nair – Read more

My name is Aditya Nair, and I specialise in wildlife photography with an added touch of surrealism. I grew up in Kenya snd couldn’t help but feel connected to the wildlife around me. Every time I saw a different species for the first time, I felt responsible for telling stories about us and them.

My name is Aditya Nair, and I specialise in wildlife photography with an added touch of surrealism. I grew up in Kenya snd couldn’t help but feel connected to the wildlife around me. Every time I saw a different species for the first time, I felt responsible for telling stories about us and them.

Several media platforms helped form my strategy of digitally capturing the true essence of nature and translating it into a format that creates a bond with anyone who views it.

Photography, videography, and editing allow me to document my relationship with these beautiful creatures. It’s an emotion rather than a conversation. The wilderness is the only place in the world I can happily wake up before sunrise and still be able to describe why!

Instagram: aditya.wildlife

Website: https://adityawildlife.com/

On a calm afternoon, I spotted a mother giraffe and her newborn calf on the plains of the Maasai Mara. As I approached them, I noticed that the calf had discomfort in its right eye, maybe due to the fall at birth. It was uplifting to see how caring the mother was. She attended incessantly, tenderly cleaning her minute son.

Judges’ comment

This lovely image reflects so beautifully the mammalian bond between mother and offspring – it evokes the mother’s affection and the calf’s (reluctant?) acceptance. The black and white with added contrast pulls the animals from the distracting wonder of the Mara backdrop.

About the photographer Ana Zinger – Read more

From Brazilian jazz clubs to Africa’s national parks, Ana Zinger sings and photographs. Born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, she majored in music and vocal performance in 2003. She developed an interest in photography at an early age, only to find her inspiration reached a peak when she visited Africa for the first time in 2000. Mesmerised by the beauty of the African wilderness, she started travelling back to Africa to photograph its wildlife. It has been 20 years now… Her work has featured in several expositions, magazines, Brazilian newspapers and Africa Geographic. Ana’s mission has been to connect people to Earth’s wild inhabitants through her lenses, throwing light on the importance of a respectful human-wildlife coexistence in a changing world.

From Brazilian jazz clubs to Africa’s national parks, Ana Zinger sings and photographs. Born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, she majored in music and vocal performance in 2003. She developed an interest in photography at an early age, only to find her inspiration reached a peak when she visited Africa for the first time in 2000. Mesmerised by the beauty of the African wilderness, she started travelling back to Africa to photograph its wildlife. It has been 20 years now… Her work has featured in several expositions, magazines, Brazilian newspapers and Africa Geographic. Ana’s mission has been to connect people to Earth’s wild inhabitants through her lenses, throwing light on the importance of a respectful human-wildlife coexistence in a changing world.

“I found myself and rediscovered photography on this continent to which I have been travelling for twenty years. In Africa, I heard my own voice whisper: ‘I am home.’ The wild places of Africa and its creatures are part of my identity, and without them, I would suffer from a profound loneliness of spirit. Photographing and being in the wild gives me a deep sense of belonging and gratitude.”

Instagram: anazinger

I almost did not go out this day; it was cold and overcast, but the need for some “phototherapy” at one of my happy places, Rietvlei Nature Reserve, overrode the urge to stay in my warm bed. I am so glad it did as I managed to capture this beautiful male yellow-crowned bishop (Euplectes afer) in full breeding plumage. He was trying his best to attract a female to his nest with his beautiful song, flaring his yellow feathers, putting on quite a show in a field of pompom weeds. While I know the pompom weeds are rapidly becoming a serious threat to the conservation of grasslands in South Africa, they do make for a colourful backdrop complimenting the stunning yellow plumage of the bishop. The moral of the story, get out of bed and explore our stunning Africa to see the beauty in even the simple things like this little bird on a stick.

Judges’ comment

It is the lovely combination of colour in this image that grabs the attention first. Then, possibly, the detail in the animated bishop’s feathers and expression. Overall the photo gives a sense of excitement at the breeding season.

About the photographer Eleanor Hattingh – Read more

I am an amateur hobby photographer raised in South Africa. I have a deep-seated love for wildlife, photography and the African bush.

I am an amateur hobby photographer raised in South Africa. I have a deep-seated love for wildlife, photography and the African bush.

I bought my Nikon camera in 2013 (I still use it today) and so began my journey in wildlife photography. Being a full time working, single mom of two amazing boys, I do not get to the bush to photograph as much as I would like, so I make the most of every opportunity. Even a day trip to the local botanical gardens or nature reserve offers great opportunities for bird photography which, in turn, has ignited a new passion for birding.

My photography has taught me to see the beauty in the simple and ordinary things that most tend to overlook in the busy lives we lead. This beauty is what I hope to share with the world through my lens.

Instagram: ella_h_333

Quench – I think it would be safe to say that 2020 turned out completely different from the way we expected it to. For a waterman and somebody whose energy is rejuvenated by spending time in the ocean, the hard lockdown in South Africa left me feeling like a fish out of water for many months.

Fortunately, I had access to a backyard facing open space. And so I started to focus my attention on the wildlife which could visit me. I set up various hides and started to observe and photograph the birds in the area.

One morning, a Cape weaver (Ploceus capensis) came to quench its thirst by catching water dripping from above. I was elated when I managed to capture, in those few fleeting moments, a perfectly shaped drop a split second before the weaver caught it, despite the slow frame rate of my camera. This moment quenched the “drought” I was feeling as much as it quenched the weaver’s thirst.

Judges’ comment

This remarkable capture radiates a sense of joy and relief of the kind that comes with harvesting Africa’s most precious resource, a resource that, as this photo demonstrates, is precious to the last drop. It’s a very tricky shot that took a great deal of patience, skill and luck.

About the photographer Geo Cloete – Read more

Geo Cloete is a multi-talented artist with an architectural degree from Nelson Mandela Bay University (South Africa) in 1999. The fruits of his labour have seen him complete award-winning works in architecture, jewellery, sculpture and photography. Sharing the beauty and splendour of the natural world, especially the underwater world, is a primary focus of his photographic projects. In recognition of his contribution to spreading awareness of ocean conservation, Geo was invited to become a Mission Blue partner in 2015.

Geo Cloete is a multi-talented artist with an architectural degree from Nelson Mandela Bay University (South Africa) in 1999. The fruits of his labour have seen him complete award-winning works in architecture, jewellery, sculpture and photography. Sharing the beauty and splendour of the natural world, especially the underwater world, is a primary focus of his photographic projects. In recognition of his contribution to spreading awareness of ocean conservation, Geo was invited to become a Mission Blue partner in 2015.

His photographic work has been awarded multiple times in many of the most prestigious national and international competitions.

Instagram: geo_cloete

The event took place in the Maasai Mara ( Olare Motorogi Conservancy) in Kenya. During a morning game drive, I saw two lionesses watching a giraffe and her calf from the cover of a croton bush. Soon the lions started stalking the giraffes and I told my guests to get their cameras ready. The lions managed to jump onto the calf, but the mother giraffe chased them away. Once the rest of the pride arrived, they surrounded the giraffes, and after about half an hour, a lioness managed to jump onto the mother’s back and distract her. During the brief separation, the lions killed the calf. The mother eventually escaped.

Judges’ comment

This is an unadulterated image that conveys the vicious side of the African wild. Although the giraffes are unable to express their emotions facially, the photo manages to display the mother’s terror and calf’s hopeless predicament. It begs the question ‘what happened next?’

About the photographer James Nampaso – Read more

I grew up in a small nomadic Maasai community in the southern part of Kenya. I now work as a professional safari guide showing international guests the beauty of nature in Olare Motorogi Conservancy.

I grew up in a small nomadic Maasai community in the southern part of Kenya. I now work as a professional safari guide showing international guests the beauty of nature in Olare Motorogi Conservancy.

I developed my photography skills by guiding many photographers from around the world and learning from them.

Instagram: jamesknampaso

On this fine morning in Kolwezi, DRC, as I gazed at a chinspot batis that was hawking insects. I noticed she wasn’t consuming her prey. Then to my surprise, she landed on a nearby nest with two chicks in it. The nest was situated on a fallen branch, allowing me to observe the birds at eye level. I visited the area during weekends, and on the 3rd week, I was lucky enough to witness the two chicks fly to a nearby branch. This image reminded me that I am one with them and one with nature.

Judges’ comment

This image just radiates warmth. The colours, the perfecton and comfort of the tastefully decorated nest, and the dedication of the mother all combine to give a sense of peace and wonder.

About the photographer Kirkamon Cabello – Read more

Kirkamon Alarin Cabello was born in the Philippines. Nature hikes led him to a love for photography at an early age. He worked as a signage layout artist in a mining company based in the Democratic Republic of Congo. During this time, he became even more enamoured with nature photography and birding. Through this art, Kirkamon eased his loneliness away from family and loved ones. It was therapy to keep him sane and happy. He has successfully entered several local competitions in the Philippines for birding photography.

Kirkamon Alarin Cabello was born in the Philippines. Nature hikes led him to a love for photography at an early age. He worked as a signage layout artist in a mining company based in the Democratic Republic of Congo. During this time, he became even more enamoured with nature photography and birding. Through this art, Kirkamon eased his loneliness away from family and loved ones. It was therapy to keep him sane and happy. He has successfully entered several local competitions in the Philippines for birding photography.

“For me, bird photography is about having a sense of connection to the environment and the audience. It is having a thousand words printed in the pixels. Photography is a never-ending passion – a desire to translate an image into a wonderful, pictorial representation – which I find both enjoyable and rewarding.”

Instagram: kirkamon

Facebook: Kirkamon Avian Photography

The ears, large and wide, manage to save this fennec fox from the sweltering weather. This is the smallest fox in the world, here immortalised while walking in the perfect dunes of the Tunisian desert. It is comfortably camouflaged despite the hostile climate of this region.

I have always been fascinated by deserts and their colours. I have long looked for an ideal location to photograph the mythical fennec fox. After much research, I decided to go to the heart of the Tunisian desert with expert guides. After several days of searching at temperatures above 45 degrees, I finally managed to immortalise my fox in its natural environment in the midst of splendid dunes.

Judges’ comment

This is an astonishing shot of a very rare and elusive animal about which little is known. That it was captured in beautiful light, with such clarity is a testament to the photographer’s determination and skill in tricky conditions.

About the photographer Marcello Galleano – Read more

Marcello Galleano, an entrepreneur in the field of nutraceuticals and herbal medicine, has always been a lover of nature and adventure trips. He has visited more than 86 countries worldwide and collaborates with non-profit associations in Africa and South America. Passionate about wildlife photography, he loves to capture the most incredible moments that the various environments offer and share the world’s beauty.

Marcello Galleano, an entrepreneur in the field of nutraceuticals and herbal medicine, has always been a lover of nature and adventure trips. He has visited more than 86 countries worldwide and collaborates with non-profit associations in Africa and South America. Passionate about wildlife photography, he loves to capture the most incredible moments that the various environments offer and share the world’s beauty.

Instagram: marcellogalleano

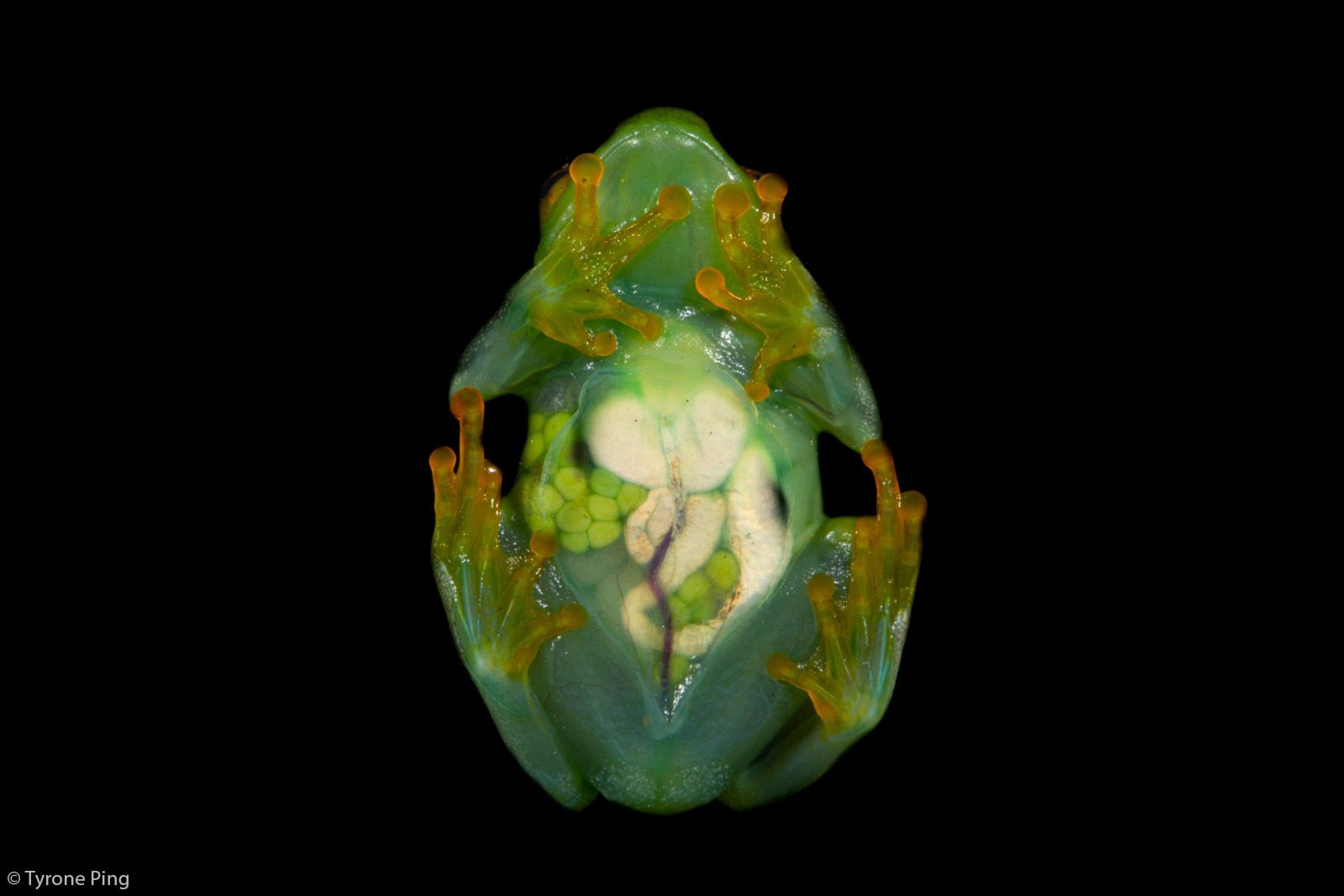

I visited the northern section of the Kruger National Park in April, a couple of months after the area had received an exceptional amount of rain accompanying cyclone Eloise. As a result, the vegetation in the area had flourished to unprecedented densities, making game viewing (and photography in particular) a real challenge. After another unsuccessful drive, we retired to our camp for the evening when a light shower provided some relief from the heat. The bush came alive when the rain subsided, and insects congregated around the camp’s lights. Among the ranks of creatures hunting them was an eruption of small amphibians brought out by the rain. I found this individual on a low hanging rain tree leaf. Backlighting by the camp’s lights and my headlamp provided the effect I was looking for. Having nothing but an ancient kit lens in my arsenal for this focal length, I was well pleased with the result. It just goes to show that there is always something to see in nature and many ways of getting interesting compositions if you just look a little closer (you also don’t always need the most expensive kit).

Judges’ comment

This image makes great use of available opportunities and imagination. The detail in the leaf is stunning, all the more so because of the lack of colour, while the frog, despite being a tiny part of the frame is the obvious star of the show.

About the photographer Mattheuns Pretorius – Read more

I am a conservation scientist, drone pilot and an avid wildlife photographer based in Gauteng, South Africa. I completed my formal training in 2007 as a nature conservation student in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, whereafter I conducted a postgraduate study on the vulnerable African Grass Owl on the Highveld of South Africa. I am currently employed by a non-profit conservation organisation. My primary role is to study novel ways to protect wildlife from power line electrocutions and collisions. I also pilot unmanned aerial vehicles for various conservation missions. My love for wildlife photography blossomed in the Kgalagadi and has since been nurtured by a passion for birding, scuba diving and various other outdoor hobbies I share with my wife.

I am a conservation scientist, drone pilot and an avid wildlife photographer based in Gauteng, South Africa. I completed my formal training in 2007 as a nature conservation student in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, whereafter I conducted a postgraduate study on the vulnerable African Grass Owl on the Highveld of South Africa. I am currently employed by a non-profit conservation organisation. My primary role is to study novel ways to protect wildlife from power line electrocutions and collisions. I also pilot unmanned aerial vehicles for various conservation missions. My love for wildlife photography blossomed in the Kgalagadi and has since been nurtured by a passion for birding, scuba diving and various other outdoor hobbies I share with my wife.

Facebook: MVP Nature Images

I took this photograph from the low water bridge over the Sabie River near Lower Sabie Camp in the Kruger National Park. It was January and extremely hot; most of the animals had retreated to the shade of tall trees in the riparian zone. This hippopotamus found relief in the cool rapids below the bridge and seemed to be thoroughly enjoying itself. Completely unperturbed by the human onlookers, it even fell into a brief midday snooze. I wanted to capture the scene in a way that brought across the peaceful expression on its face and opted for a slow shutter speed to enhance the feel of flowing water around the hippo in its ‘natural jacuzzi’.

Judges’ comment

This is such a cleverly designed and considered, artistic shot. The sharpness of the hippo contrasting with a blur of the water and the expression of apparent relaxation of the hippo’s face are utterly captivating.

About the photographer Mattheuns Pretorius – Read more

I am a conservation scientist, drone pilot and an avid wildlife photographer based in Gauteng, South Africa. I completed my formal training in 2007 as a nature conservation student in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, whereafter I conducted a postgraduate study on the vulnerable African Grass Owl on the Highveld of South Africa. I am currently employed by a non-profit conservation organization. My primary role is to study novel ways to protect wildlife from power line electrocutions and collisions. I also pilot unmanned aerial vehicles for various conservation missions. My love for wildlife photography blossomed in the Kgalagadi and has since been nurtured by a passion for birding, scuba diving and various other outdoor hobbies I share with my wife.

I am a conservation scientist, drone pilot and an avid wildlife photographer based in Gauteng, South Africa. I completed my formal training in 2007 as a nature conservation student in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, whereafter I conducted a postgraduate study on the vulnerable African Grass Owl on the Highveld of South Africa. I am currently employed by a non-profit conservation organization. My primary role is to study novel ways to protect wildlife from power line electrocutions and collisions. I also pilot unmanned aerial vehicles for various conservation missions. My love for wildlife photography blossomed in the Kgalagadi and has since been nurtured by a passion for birding, scuba diving and various other outdoor hobbies I share with my wife.

Facebook: MVP Nature Images

I captured this image of a Hartlaub’s Gull at ‘The Kom’, in the seaside village of Kommetjie situated in the South Peninsula of Cape Town.

The morning the image was taken, ‘The Kom’ was calm and glassy. The gulls were jumping and diving, a perfect scenario to capture the Hartlaub’s Gull in action with a partial reflection in the still water.

‘The Kom’ is a small sheltered bay almost entirely enclosed by a ridge of boulders which was once a Stone Age fish trap. When conditions are right, it is one of the best sites on land from which to see seabirds.

Judges’ comment

This is a perfectly timed image from a wonderful angle that probably took a good deal of patience and experimentation to achieve. The edit really makes the bird and the water pop out of the background.

About the photographer Philip Jackson – Read more

Philip Jackson was born in the United Kingdom. In 1992, at the age of 28, in need of adventure and tired of grey skies, he embarked on a bicycle ride to South Africa to start a new life. He fell in love with the country and has lived there ever since.

Philip Jackson was born in the United Kingdom. In 1992, at the age of 28, in need of adventure and tired of grey skies, he embarked on a bicycle ride to South Africa to start a new life. He fell in love with the country and has lived there ever since.

Being a nature lover his whole life, it was finally the lure of birds that encouraged him to pick up a camera and start photographing all things feathered. Seven years later, his passion for bird photography is still on an upward trajectory. He is often spotted wading into swamps, oceans, rivers or bushes in an attempt to capture the perfect bird shot. Philip now resides in Imhoff’s Gift, on the edge of Wildevoelvlei in the Western Cape. He is fortunate enough to have fish eagles, swamp hens, pied kingfishers, flamingos and many other bird species on his doorstep.

Instagram: featheredpics

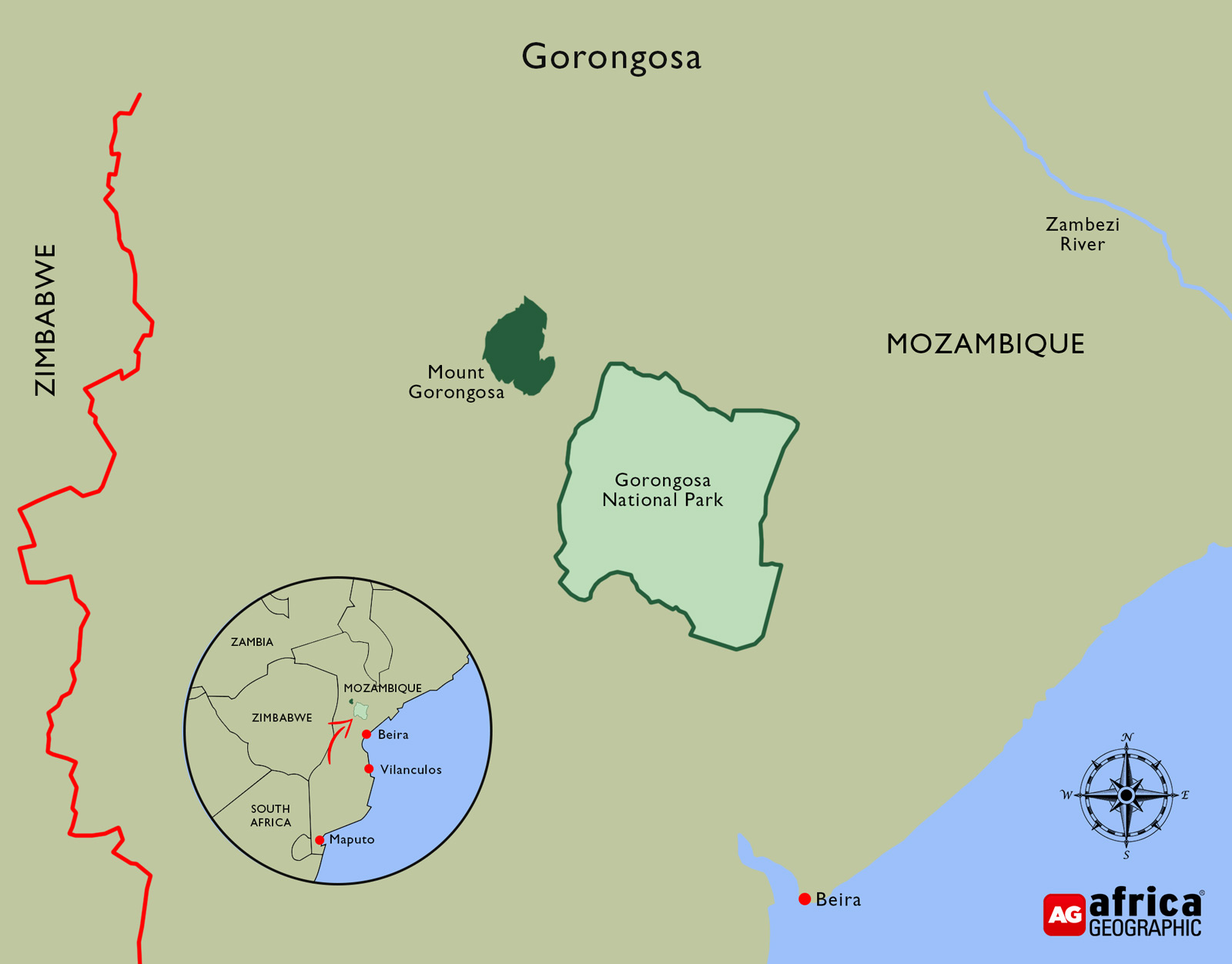

The graceful Mozambican long-fingered bat (Miniopterus mossambicus) is a fast-flying predator of insects, targeting them with echolocation signals emitted through the open mouth (many bats echolocate through the nose). A large colony of this species lives in the limestone caves of the Cheringoma Plateau in Gorongosa National Park. They emerge at dusk to hunt moths and beetles before returning to the safety of their cave shortly before sunrise. I took this photo using an infrared beam that triggered the camera as soon as the bat broke it with its body.

Judges’ comment

Photographing bats on the wing, especially the nocturnal ones, is very tricky. This image is a great example of the skillful use of technology combined with an artistic eye and a great understanding of the subject’s behaviour.

About the photographer Piotr Naskrecki – Read more

Piotr Naskrecki is an entomologist, conservation biologist, and photographer with over 20 years of experience in biodiversity research in academic environments and non-profit conservation organisations. He received his PhD in entomology from the University of Connecticut, USA. His interests concentrate on sound communication in insects and other animals, new species discovery, biodiversity conservation, and popularisation of scientific knowledge.

Piotr Naskrecki is an entomologist, conservation biologist, and photographer with over 20 years of experience in biodiversity research in academic environments and non-profit conservation organisations. He received his PhD in entomology from the University of Connecticut, USA. His interests concentrate on sound communication in insects and other animals, new species discovery, biodiversity conservation, and popularisation of scientific knowledge.

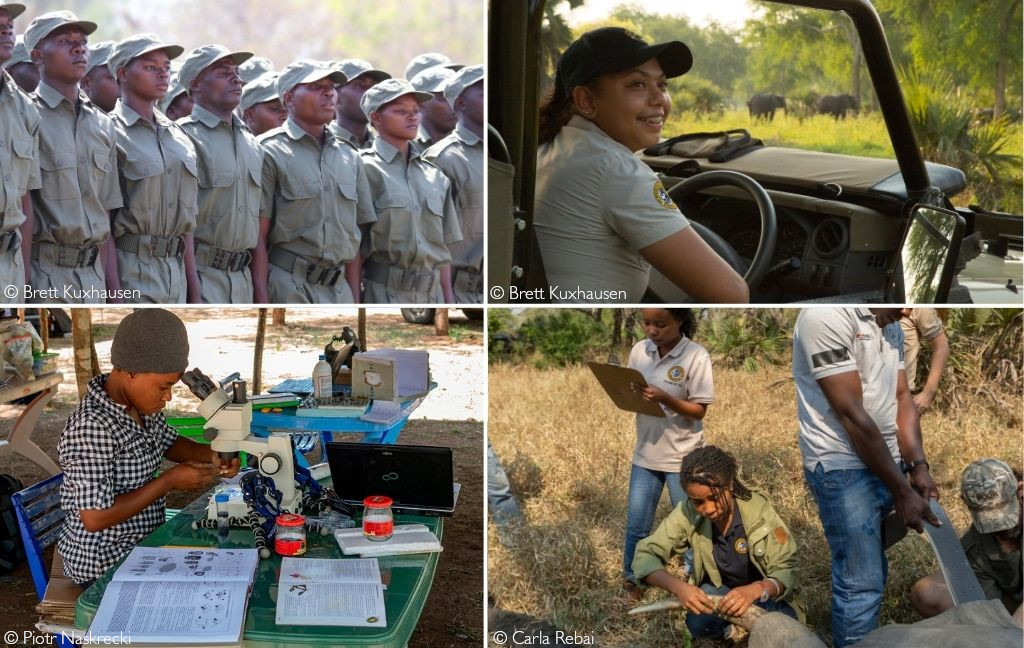

Piotr has published over 60 peer-reviewed papers, several books, and numerous popular articles. He has discovered and described over 150 species new to science, including new katydids, crabs, bats, and lizards. He has conducted biodiversity research and led expeditions in tropical areas across the globe. Currently, he directs the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Laboratory in Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique, where he designed and helped create a unique research and education facility that includes a molecular laboratory, biological synoptic collections, and a comprehensive bioinformatics infrastructure. He has also initiated and helped develop an extensive biodiversity education program for Mozambican students, including Mozambique’s first graduate program leading to the M.Sc. degree in conservation biology, all in the remote wilderness of Gorongosa.

He is actively involved in the work of the IUCN Red List and serves as the first Chair of the Half-Earth Project of the E.O. Wilson Foundation, leading the Half-Earth Scholars initiative in Mozambique. In addition to conservation and education work in Mozambique, he has an active research program in systematics and insect behaviour, including a comparative study of acoustic and other behavioural responses of katydids to bat echolocation in the Old World (Mozambique) and the New World (Costa Rica).

Piotr is also an accomplished photographer whose images have been among the winners of major competitions, such as the Big Picture and Wildlife Photographer of the Year. He has authored several books illustrated with his photos (“The Smaller Majority”, “Relics”, “Hidden Kingdom”).

Instagram: piotr_naskrecki

Website: https://thesmallermajority.com/about/

Marimba is a Ground Pangolin. Like many others of her species, her mother was poached for her scales to be used in traditional Chinese medicine. Marimba was thought to have been just a year old when she was orphaned – too young to fend for herself. The decision was therefore made to take her to the Wild is Life sanctuary in Harare, Zimbabwe, where she met her full-time carer, Mateo.

Pangolins are notoriously difficult to look after in captivity and require particular and personal care. Mateo’s gentle nature seemed like a perfect fit, and a remarkable relationship was born.

Pangolins are naturally nocturnal. However, for their safety, Marimba and Mateo go out in the day so she can satisfy her insatiable appetite for specific species of ants and termites. Marimba and Mateo have spent ten hours a day together for the past thirteen years, and it shows – they are inseparable. Many attempts have been made to rewild Marimba, but she always finds a way back to Mateo. She is simply too attached to him, and being so young when her mother died, she never learnt the essential skills required to survive in the wild.

As Marimba cannot be released, she will live the rest of her life at the sanctuary as an ambassador for her species. Her story has already touched the lives of so many, highlighting the importance of protecting these wonderfully unique creatures so that others do not succumb to the same fate as her mother.

Do not be fooled by their reptilian appearance. Pangolins are affectionate, gentle, sentient beings that are rapidly disappearing from our planet. They are the most trafficked group of animals in the world, and unfortunately, most human-pangolin interactions end in another pile of lifeless scales.

In a perfect world, the close connection between Marimba and Mateo would have never existed. However, I hope that this image portrays the relationship that we as a species should strive to have with pangolin to save them from extinction—one of trust, love, and compassion.

Judges’ comment

The story told by this powerful image is both sad and encouraging – speaking of humanity’s destruction of nature and of the selfless commitment many have made to save our most vulnerable species.

About the photographer Sam Turley – Read more

Sam Turley was born in Staffordshire, England, in 1992. Growing up in the countryside, Sam’s fascination with the natural world started at a very young age and has never left him. He has since dedicated his life to wildlife conservation, and after studying zoology in the UK, he went on to qualify as a field guide in South Africa, where he worked for three years. During a trip to Namibia in 2016, Sam’s passion for wildlife photography ignited, and he has been obsessed ever since. He was the overall winner of the 2020 Wilderness Safaris People’s Choice Award and was a three-time finalist in the highly prestigious 2020 Natural History Museum’s Photographer of the Year competition. His work has also been featured in many magazines, including The Telegraph, Getaway and Travel Africa. He now lives and works in Zimbabwe on a rhino conservancy where he plans to run photographic workshops and tours.

Sam Turley was born in Staffordshire, England, in 1992. Growing up in the countryside, Sam’s fascination with the natural world started at a very young age and has never left him. He has since dedicated his life to wildlife conservation, and after studying zoology in the UK, he went on to qualify as a field guide in South Africa, where he worked for three years. During a trip to Namibia in 2016, Sam’s passion for wildlife photography ignited, and he has been obsessed ever since. He was the overall winner of the 2020 Wilderness Safaris People’s Choice Award and was a three-time finalist in the highly prestigious 2020 Natural History Museum’s Photographer of the Year competition. His work has also been featured in many magazines, including The Telegraph, Getaway and Travel Africa. He now lives and works in Zimbabwe on a rhino conservancy where he plans to run photographic workshops and tours.

“My unique background in zoology and my experiences working as a guide help me to understand complex conservation issues. Through my photography, I aim to highlight and celebrate successful conservation initiatives whilst connecting audiences to the natural world on an emotional level. I believe that our relationship with the natural world has never been more important than it is today. I hope that my images help people to fall in love with wildlife and to ultimately understand the importance of protecting it. For, in the end, we will only conserve what we love.”

Instagram: samturleyphoto

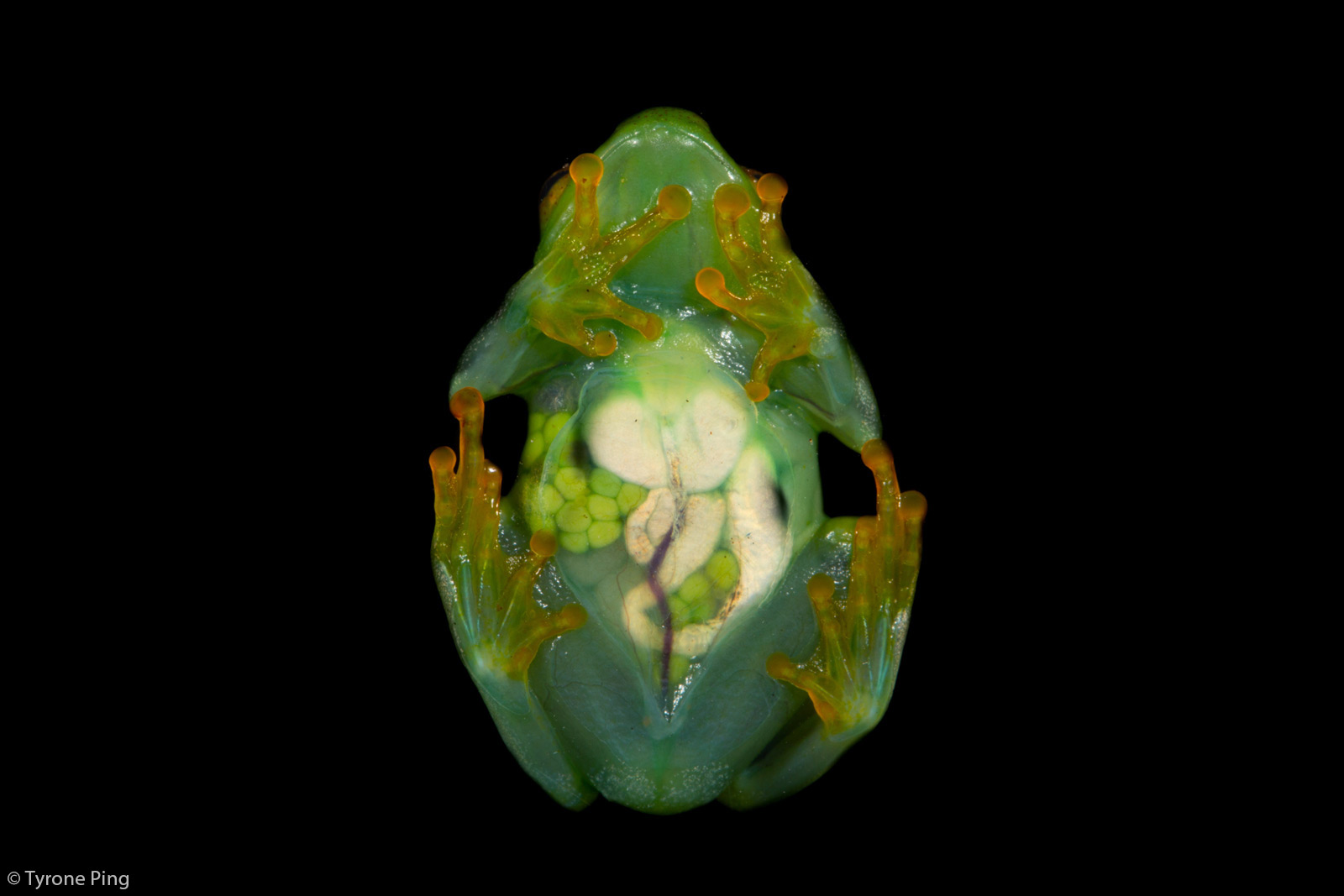

It was a particularly rainy December in Hillcrest, the garden shrubs and trees green and growing. The insects, including flies and mosquitoes, were also thriving.

On this morning, I happened to see a little tree frog hiding in a Ligularia leaf which is a bushy plant that attracts lots of flies and insects when in flower. Of course, not to miss a wonderful opportunity, I ran to grab my camera, which happened to have a flash attached to it. I managed to take several shots before the frog disappeared into the leafy trees above. My settings were Manual Mode, F16, shutter speed 100, ISO 800, Macro lens, handheld.

Judges’ comment

This image is beautifully presented. The way the frog is looking at the camera, his right foot draped leisurely over the edge of his leafy refuge, gives a sense of fairy tale curiosity and joy. The gentler side of nature.

About the photographer Shirley Gillitt – Read more

I was born and educated in Zimbabwe, moved to KwaZulu Natal, South Africa to complete a midwifery diploma as a young woman and married a South African farmer who is passionate about wildlife. So it was that my interest in wildlife and photography slowly began.

I was born and educated in Zimbabwe, moved to KwaZulu Natal, South Africa to complete a midwifery diploma as a young woman and married a South African farmer who is passionate about wildlife. So it was that my interest in wildlife and photography slowly began.

I am an amateur photographer who takes photography seriously, exploring most genres. However, my passion is wildlife, a genre that requires patience, perseverance and observance. To watch and understand animal behaviour is hugely rewarding for me. The abundance of game reserves available to us is an absolute privilege, and we try to visit most as much as possible. On many trips to game reserves, I spend time admiring the small creatures, birds and flora while trying to bypass the other 80% of people chasing the big five.

I live in Hillcrest, KwaZulu Natal, a subtropical temperate climate where the tree frogs hang out.

Instagram: shirleygillitt

I have been lucky and privileged to have visited the mountain gorillas of Bwindi in Uganda a few times and what surprises me the most each time I encounter them is how similar they are to us. I was attracted to this silverback who was very relaxed and lying down, observing my movements and keeping a close eye on the rest of us.

His hands caught my attention; I was amazed at how similar they are to our human hands. Perhaps they are not like modern-life hands, but rather hands that have worked and harvested – like a farmer without modern machinery.

Judges’ comment

This image somehow manages to convey contemplation, power and vulnerability all at once. The hands’ likeness to our own also demonstrates humanity’s connection to nature and wilderness

About the photographer Valentino Morgante – Read more

From Italian origins, Valentino Morgante was born in Malawi, in the heart of Africa, where he spent his first 18 years living in close contact with African nature and culture. He completed his last years of study in Johannesburg and then moved to Italy. There, he began his working life, where he developed, among other things, a passion for nature and sports photography.

From Italian origins, Valentino Morgante was born in Malawi, in the heart of Africa, where he spent his first 18 years living in close contact with African nature and culture. He completed his last years of study in Johannesburg and then moved to Italy. There, he began his working life, where he developed, among other things, a passion for nature and sports photography.

In the 90s, the call of Africa brought him back to his native land, this time to Namibia, where he started as a specialised tour guide and then a tour operator. Valentino is still living his dream and leads small groups of photographers to iconic African parks. His unconditional love for Africa is clearly recognisable in his passion for nature photography, which represents an artistic expression capable of enhancing the beauty of African nature and wildlife.

Instagram: valentino_morgante

I visited Kenya for photography in 2019. The trip aimed to capture Kenya’s natural scenery, wild animals, and local people. On this day, before dawn, we drove from the Lentorre Lodge, where we stayed to a nearby village of Maasai people. When we arrived, the village was just coming alive. The children began to play, and the adults drove the cattle and sheep. Animals are important assets to the Maasai people, and animal husbandry is their main source of livelihood. This was an unforgettable day in my photography career.

Judge’s comment

This image has so many layers to it. The glorious colours of the dawn and the Maasai shukas, the movement of the goats and sheep, the children playing to the left and the dust. It also manages to convey a sense of peace and daily rhythm.

About the photographer Ying Shi – Read more

Ying Shi is a Chinese photographer who has lived in Canada for nearly 20 years. He is a member of the Canadian Association For Photographic Art, a council member of the Jiahua Elite Photography Association, and a member of the Photographic Society of America. He was awarded The Distinguished Canadian Photographer by the 126th Toronto International Salon of Photography in 2019. His photographs in Kenya have won many awards in international photography competitions.

Ying Shi is a Chinese photographer who has lived in Canada for nearly 20 years. He is a member of the Canadian Association For Photographic Art, a council member of the Jiahua Elite Photography Association, and a member of the Photographic Society of America. He was awarded The Distinguished Canadian Photographer by the 126th Toronto International Salon of Photography in 2019. His photographs in Kenya have won many awards in international photography competitions.

WATCH:

WATCH:

We have an epic newsletter for you this week – so please budget for EXTRA TIME because each of the five stories below is an excellent read.

We have an epic newsletter for you this week – so please budget for EXTRA TIME because each of the five stories below is an excellent read.

The world’s most famous lion died last week. Scarface, famed king of the Maasai Mara, breathed his last while resting comfortably in the waving red oat grass. He wasn’t shredded by hyenas or mauled by young pretenders. This is not a death that many wild animals can look forward to. To some, Scarface was a controversial figure. He was given the benefit of at least ten veterinary interventions that probably extended his ‘natural life’. Far more than that, however, he was an ambassador for his species and for wilderness in general. Who knows how many tourist dollars came to the Mara, contributing to the preservation of wild places because of this grizzled legend of the plains. His image, which hangs in homes all over the world, will continue to inspire nature travel and a passion for Panthera leo.

The world’s most famous lion died last week. Scarface, famed king of the Maasai Mara, breathed his last while resting comfortably in the waving red oat grass. He wasn’t shredded by hyenas or mauled by young pretenders. This is not a death that many wild animals can look forward to. To some, Scarface was a controversial figure. He was given the benefit of at least ten veterinary interventions that probably extended his ‘natural life’. Far more than that, however, he was an ambassador for his species and for wilderness in general. Who knows how many tourist dollars came to the Mara, contributing to the preservation of wild places because of this grizzled legend of the plains. His image, which hangs in homes all over the world, will continue to inspire nature travel and a passion for Panthera leo.

Travel writer, mountain guide and mother, Sarah Kingdom was born and brought up in Sydney, Australia. Coming to Africa at 21, she fell in love with the continent and stayed. Sarah guides on Kilimanjaro several times a year, and has lost count of how many times she has stood on the roof of Africa. She has climbed and guided throughout the Himalayas and now spends most of her time visiting remote places in Africa. When she is not travelling, she runs a cattle ranch in Zambia with her husband.

Travel writer, mountain guide and mother, Sarah Kingdom was born and brought up in Sydney, Australia. Coming to Africa at 21, she fell in love with the continent and stayed. Sarah guides on Kilimanjaro several times a year, and has lost count of how many times she has stood on the roof of Africa. She has climbed and guided throughout the Himalayas and now spends most of her time visiting remote places in Africa. When she is not travelling, she runs a cattle ranch in Zambia with her husband.