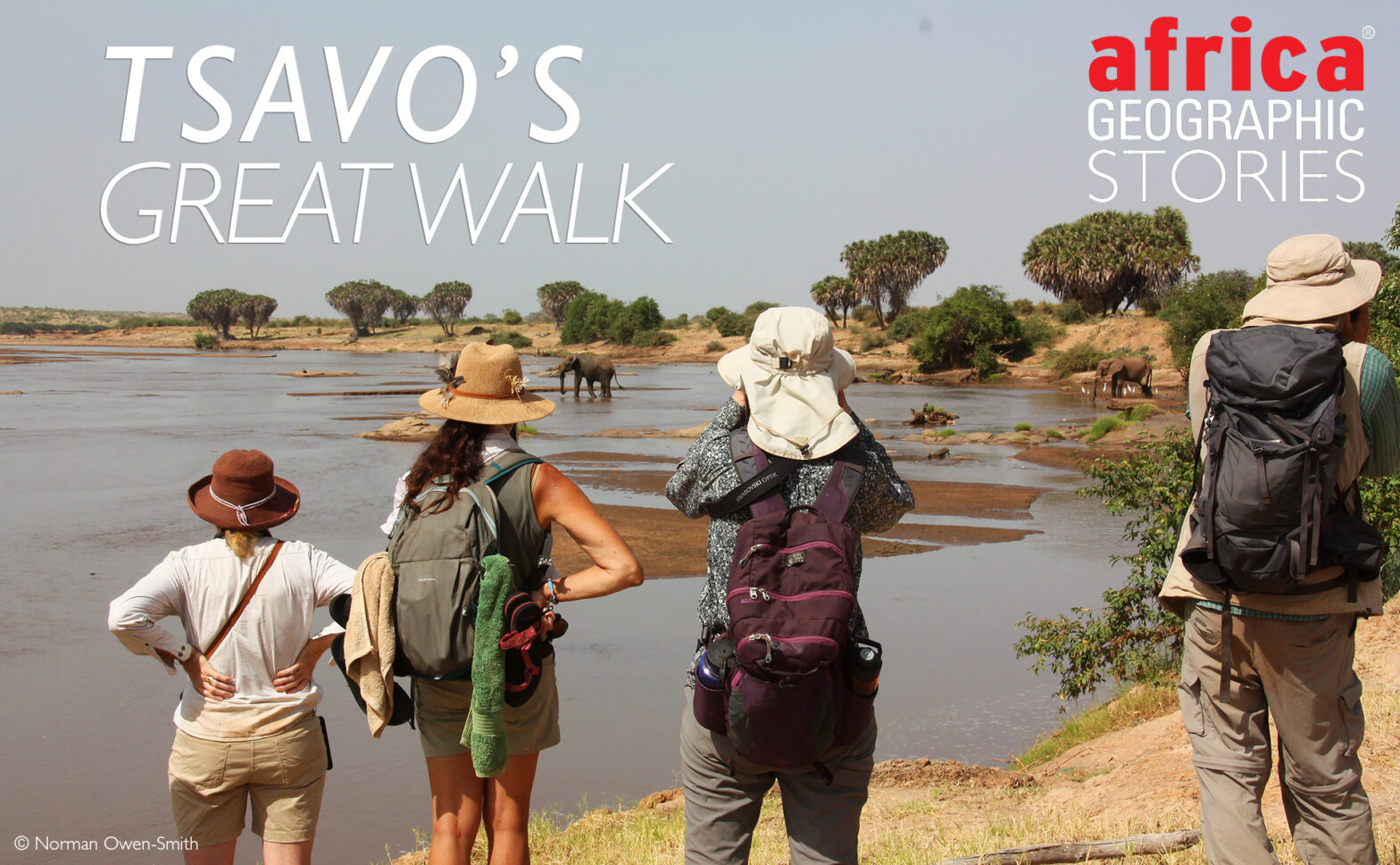

I recently had the privilege to realise my lifelong dream of travelling across Tsavo National Park in Kenya on foot on the ‘Great Walk’ with Africa Geographic. I was confident that, even at 80, I could meet the goal of covering 160 km (100 miles) over ten days of walking.

Moreover, I desperately needed to break out of the confines imposed by the pandemic, which had scuttled several planned trips. This expedition to the kingdom of elephants offered an opportunity to remain almost entirely in the open air in a remote area, minimising the risk of infection.

Tsavo’s tumultuous history

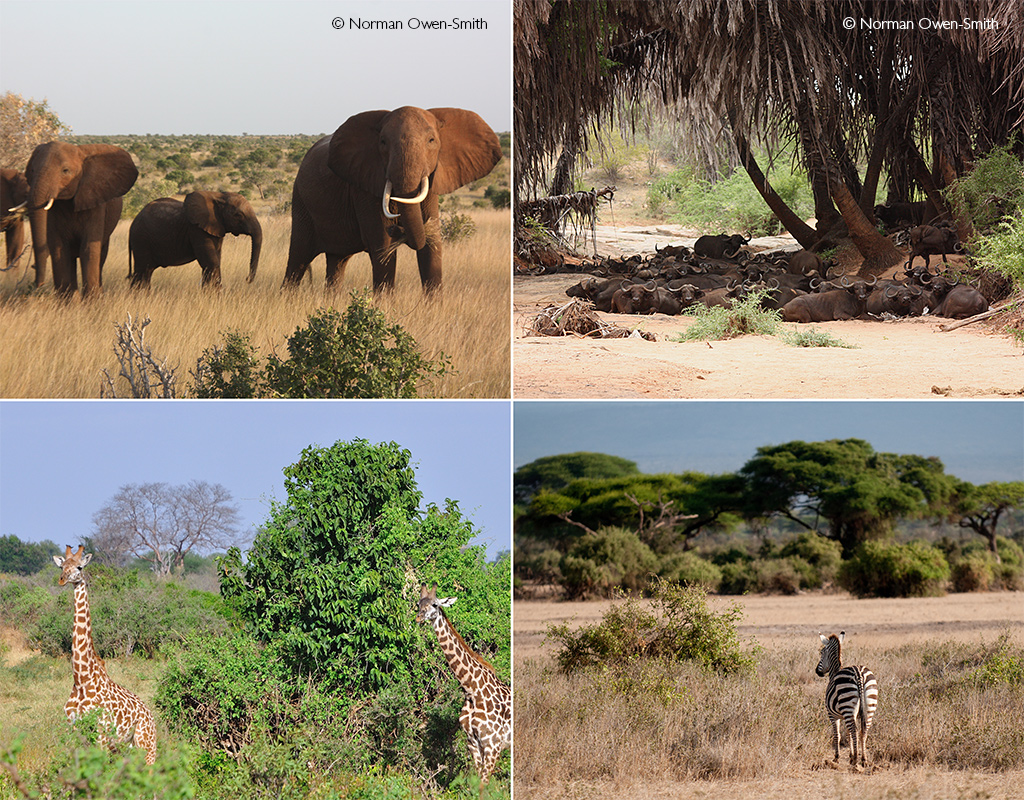

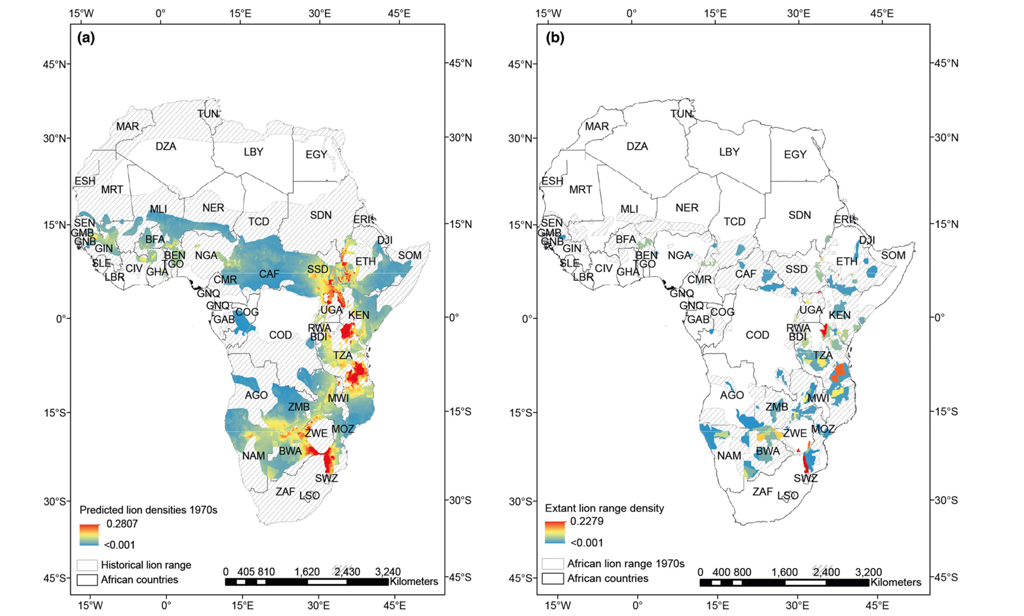

Tsavo National Park has a rich, at times tumultuous, history. In 1898, two maneless lions terrorised workers constructing the railway from Mombasa to Nairobi, where it crossed the Tsavo River, devouring at least 28 people before they were shot (providing the subject for the film The Ghost and the Darkness). After the park was proclaimed in 1946, the elephant population grew so rapidly that scientists called for culling. The population was later reduced when at least 6,000 elephants died in the park during a severe drought in the early 1970s. The death toll was mostly made up of mother elephants and calves confined to the vicinity of the Galana River, where food had run out. This was followed by rampant poaching, which reduced the park’s elephant population from around 25,000 to little more than 5,000. By 1989, black rhinos had been nearly wiped out by poaching. Since then, the vegetation has been recovering, while the elephant population has grown to around 12,000. By 1995, when I first visited the park, signs of past damage by elephants were not very apparent, apart from the absence of baobab trees. But it was challenging to make a fair assessment back then from the confines of a motor vehicle.

The Great Walk of Tsavo

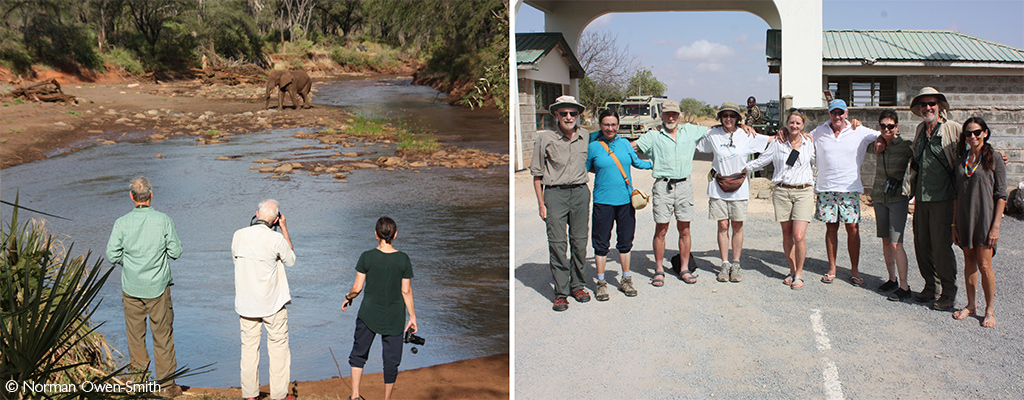

Fast forward to our Great Walk this year. Our walking route followed the Tsavo River from where it enters Tsavo in the west to its junction with the Athi River and continued along the Galana River to exit the park in the east. This Great Walk is a single segment of a much longer expedition, travelling from the summit of Kilimanjaro to the ocean north of Mombasa, a distance of 480 km+. Our walk through elephant country was lavishly supported in camp facilities and food by a team that shifted tents and fresh supplies from one campsite to the next as we traversed the wild, roadless areas on the opposite side of the two rivers. We had to wade across rivers to link our walking route to the campsite. Although the water was no more than thigh deep, there was no guarantee that a crocodile wouldn’t appear, adding to the thrill of the journey. However, we were well protected by skilled armed guides stationed at the front and back of our walking party.

A reasonable degree of fitness is needed to meet daily distance targets of 15 km or more, especially during the midday heat. Our guide, Iain Allan, conveyed much of his 40 years of knowledge of the region and its history, of films old and new, and of his travels as an accomplished mountaineer. He has never tired of leading another walking expedition through Tsavo because each provides unique experiences.

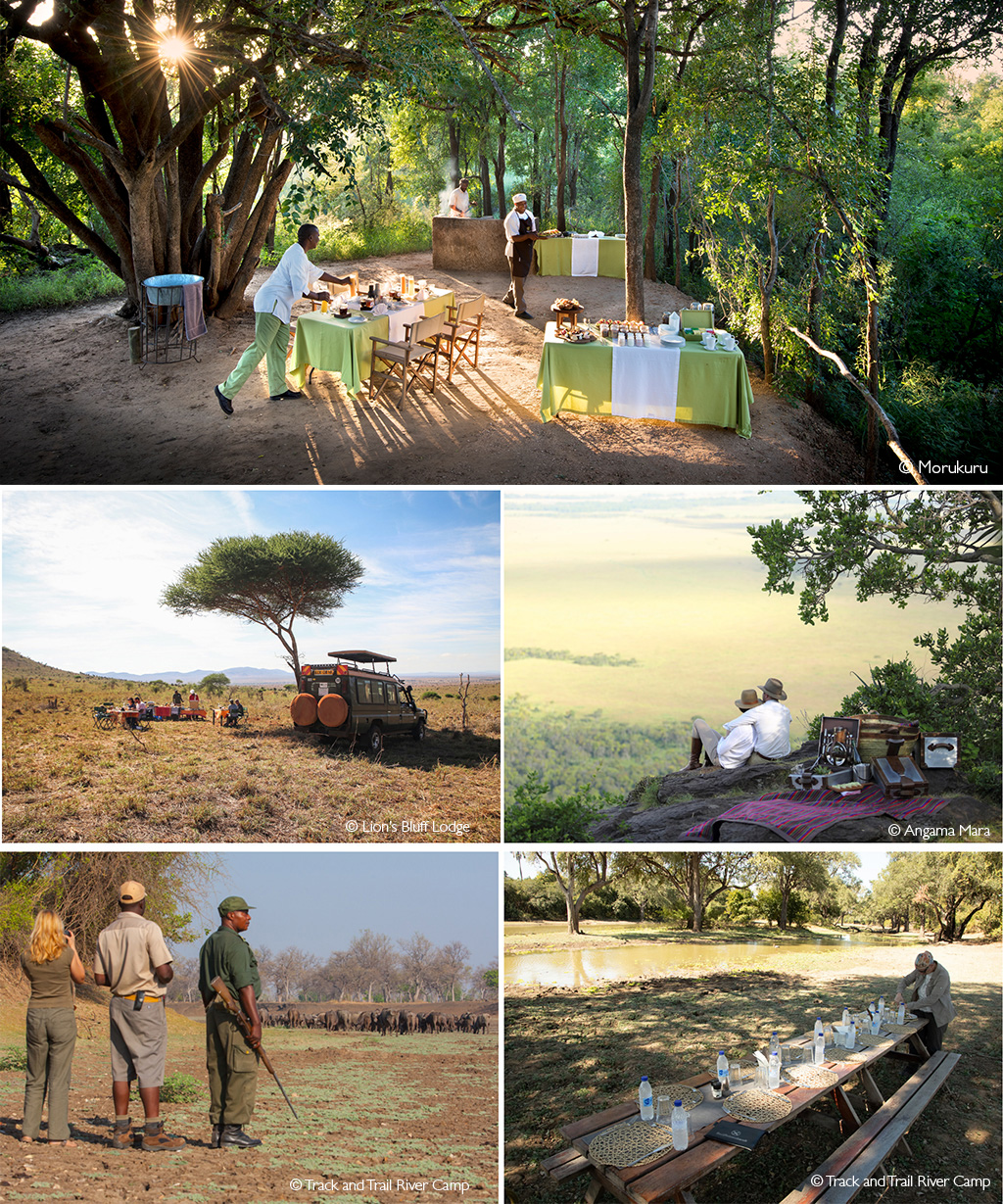

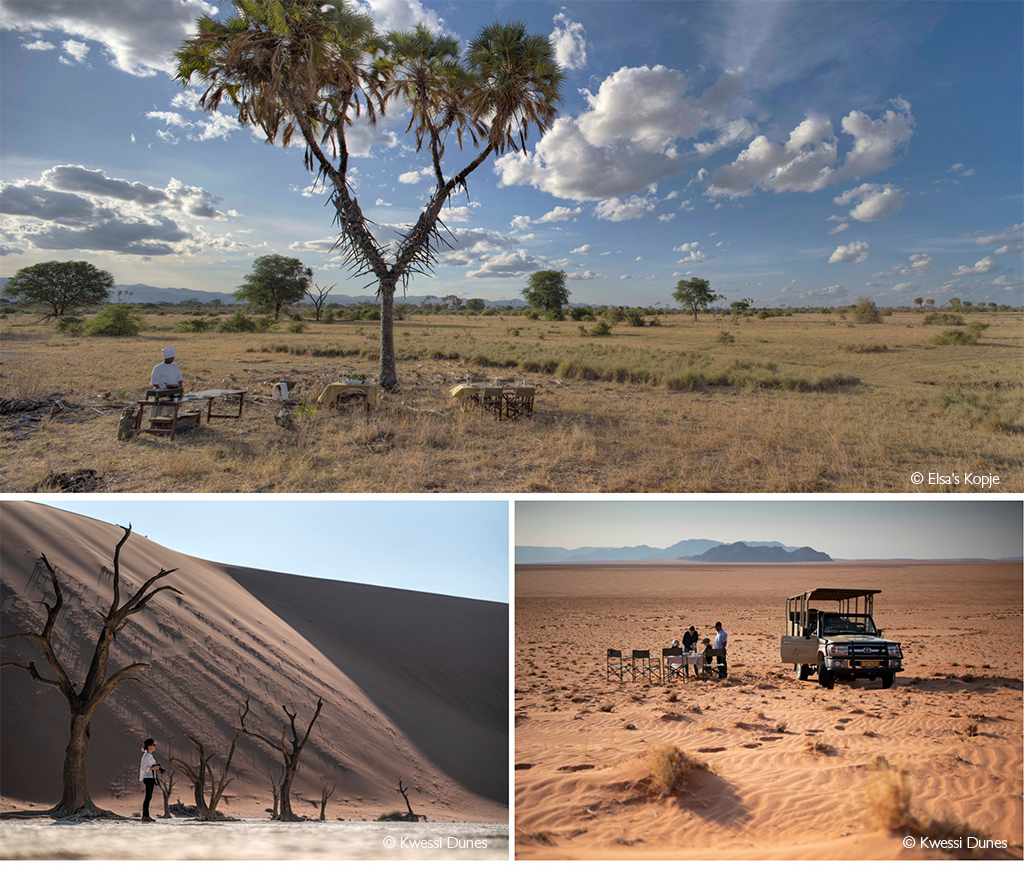

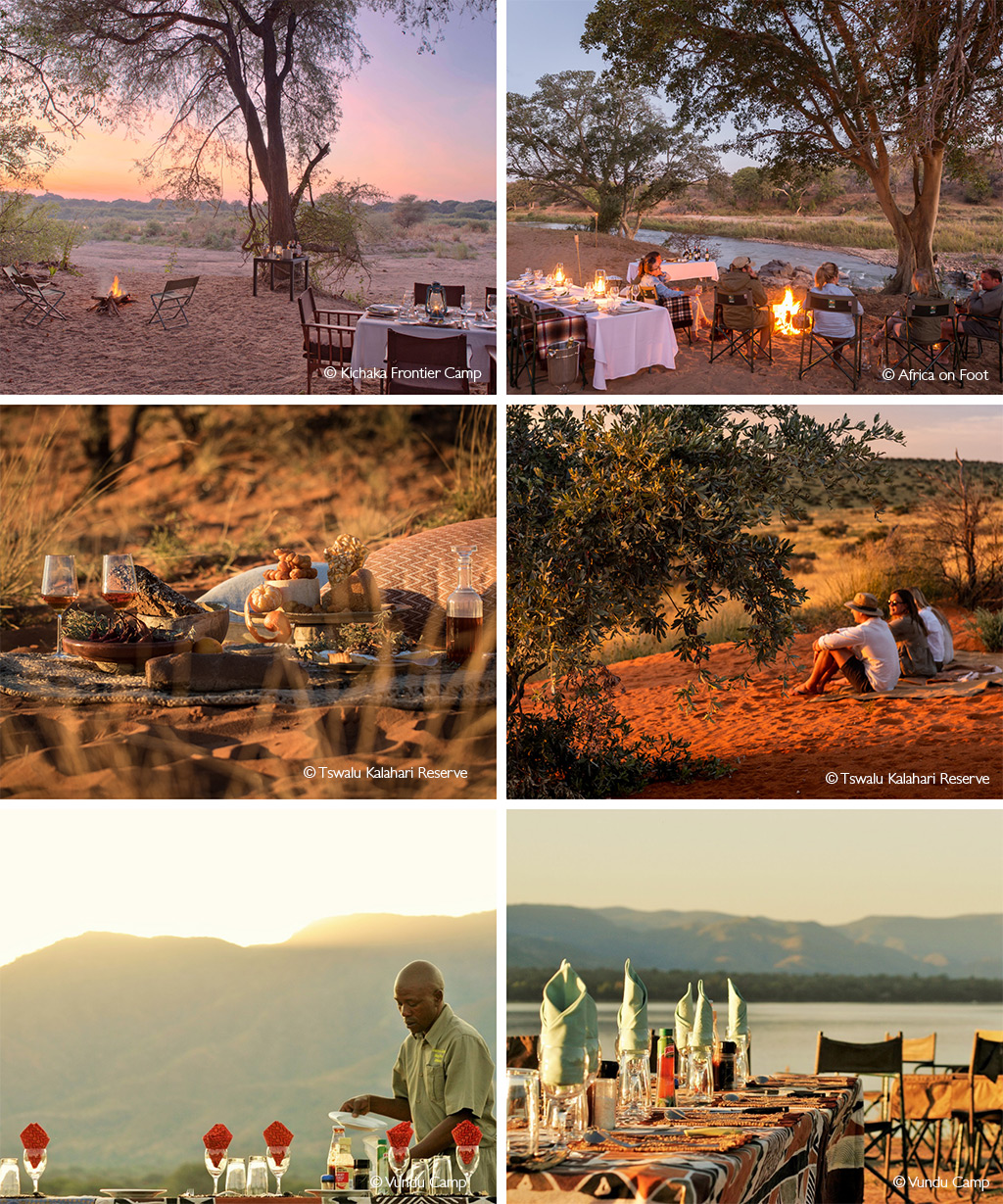

Our group consisted of eight people, including my wife and me, two couples from the USA who had been on many expeditions, and two women from Australia. Our daily walk began each morning at 7:00 and ran until 13:00. Afterwards, we would enjoy a cooked lunch with fresh salads and fruit. After lunch, we spent the afternoons resting until it was time for a game drive. This was followed by sundowners overlooking the river alongside our camp. These sundowners, gathering us around the river’s varied views at dusk, were especially delightful.

Camping arrangements provided the luxury of comfortable beds, each tent with its own little pit toilet and bucket shower, plus expertly cooked meals.

Wild experiences

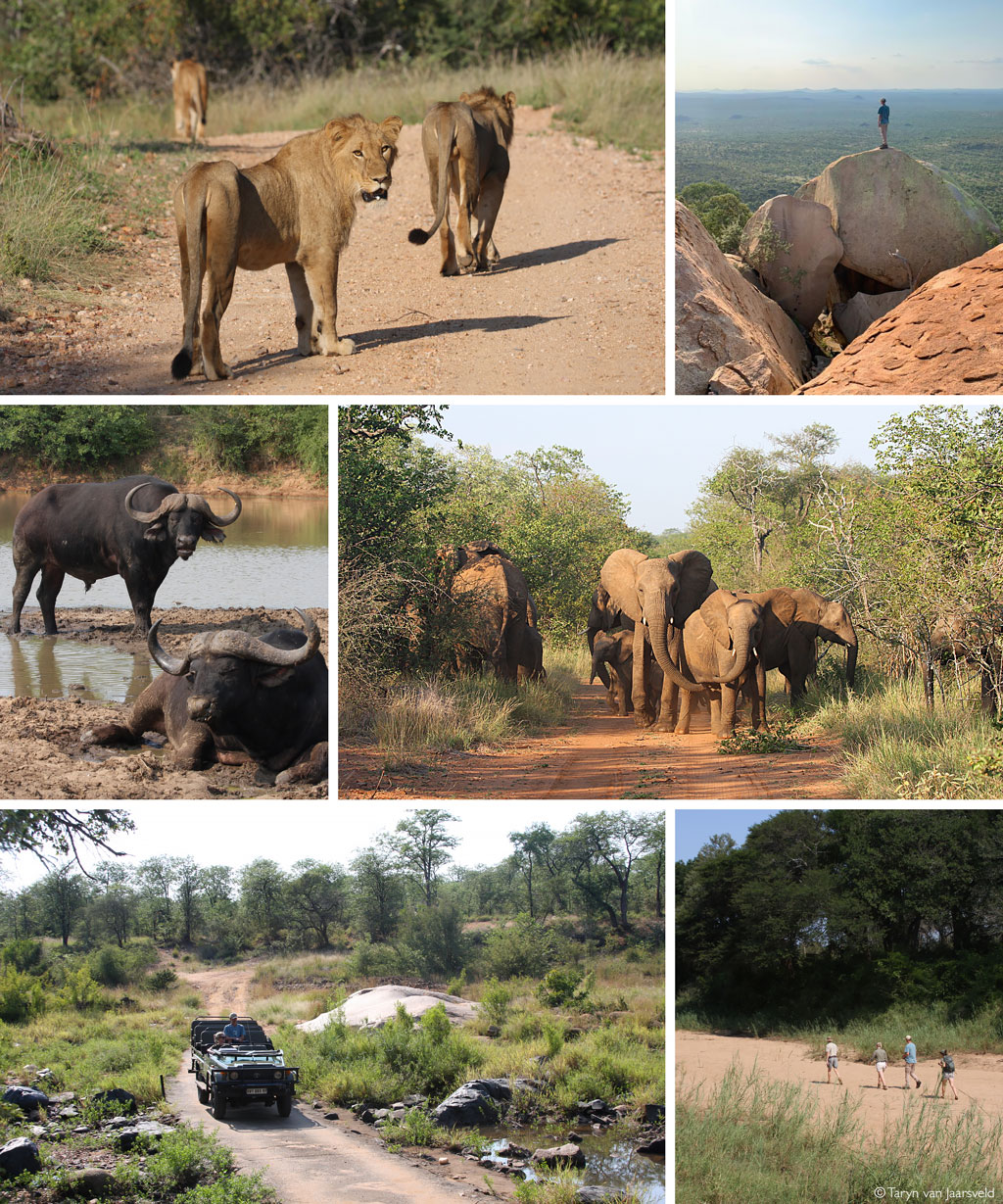

This trip provided several memorable encounters. We walked through dense shrubbery along hippo paths, trusting that the hippos would be in their aquatic refuges during the day, yet still facing the prospect of close encounters with elephants and buffalo. Thankfully, all the hippos we saw while walking were in the river, but we were aware of incidents on previous walks when walkers had to be protected from charging hippos. Charging elephants have also, on occasion, been deflected by warning shots. Crocodiles have not caused any injuries, but every precaution was taken to cross rivers in shallow water, as elephants do. The group was kept tightly bunched until we reached the safety of land. The vegetation near the Galana River is much more open and grassy, which allowed us to see animals at a distance, and vice versa – apart from the dense salt-bush shrubbery that we had to traverse frequently to get to or from the river.

Elephants revved us twice. Once, just as we entered a tricky section of thick vegetation between the Tsavo River and a steep rocky slope, there was a loud trumpet, and our guide urged us to head back hastily and ascend the hill as high up as we could. Our passage had been blocked by a giant bull elephant, evidently in musth. Fortunately, he deviated up the slope, and we were able to traipse cautiously past.

The second incident involved two female elephants in a family group. They headed towards us with a loud trumpet, but veered off when we retreated hastily. We passed by many other elephants, but most remained oblivious to our presence.

We had another fright when a buffalo bull galloped out of a salt-bush clump just behind us, heading off as fast as he could.

Even more thrilling were the three encounters we had with lions. In two instances, the lions were sleeping, and we crept on without disturbing them. On the third occasion, two lions ran off across the river when we appeared close by. Fortunately, the lions of Tsavo have not retained any tradition of hunting humans, preferring buffalo.

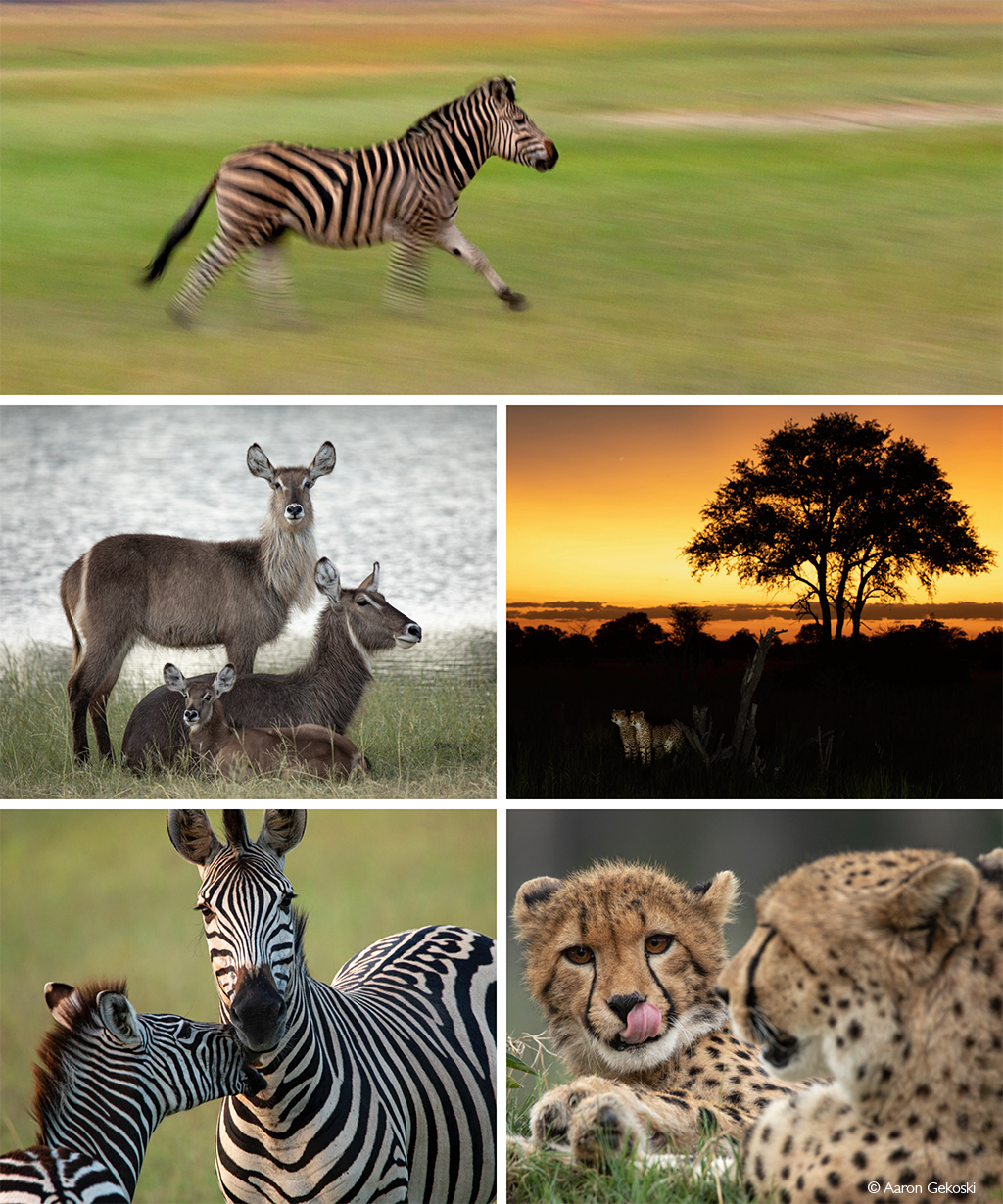

We enjoyed sightings of giraffe, zebra, fringe-eared oryx, waterbuck, Peter’s gazelle (a subspecies of Grant’s gazelle), impala, hartebeest, dik-dik, a single lesser kudu, two gerenuk and even a brief glimpse of a honey badger – with most sightings taking place in the open dry country north of the Galana River. Once abundant in the region, black rhinos are now rarely seen. I wondered how we would have coped with these cantankerous animals puffing towards us out of the thickets.

We saw many birds; most notably, huge swarms of queleas and a gathering of Somali bee-eaters around a Delonyx tree that was in flower and attracting bees. Among the reptiles, we saw just one snake – a cobra – and a large monitor lizard. Among insects, it was fascinating to see large numbers of white Belanois butterflies around Boscia bushes, fluttering westwards. Were they connected with the similar butterflies that we see flying in the Highveld in mid-summer, going east, perhaps in some great spiral? Surprisingly, we did not experience mosquitoes or tsetse flies.

The experience of being completely immersed in the wild Africa that shaped the evolution of our species for two whole weeks is unique to this Great Walk. Tsavo National Park is fascinatingly different from other East African parks in its landscapes, vegetation and fauna.

Resources

Want to head out on the Great Walk? Join AG on this amazing safari to experience Tsavo on foot.

Want to visit Tsavo National Park? Read about Tsavo – the land of legends – here.

Guests of Africa Geographic went on an 80km walking trail to follow giants in Tsavo – read more about their experience here.

For more by the author, check out Norman Owen-Smith’s book, Only in Africa: The Ecology of Human Evolution

Christina Hagen, Project Rep for Birdlife South Africa’s African Penguin Conservation project, writes on the

Christina Hagen, Project Rep for Birdlife South Africa’s African Penguin Conservation project, writes on the

So where did they go? Well, no one knows for sure, but (somewhat unsurprisingly) their disappearance seems to

So where did they go? Well, no one knows for sure, but (somewhat unsurprisingly) their disappearance seems to

Maggie Nunley and her partner are currently on a cross-continental adventure with AG, celebrating their honeymoon. The couple started their adventure in Mgahinga National Park in Uganda and moved on to Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. They are finishing off their African holiday with a trip to Chale Island off Kenya’s Diani Beach to deflate in the warm waters of the Indian Ocean.

Maggie Nunley and her partner are currently on a cross-continental adventure with AG, celebrating their honeymoon. The couple started their adventure in Mgahinga National Park in Uganda and moved on to Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. They are finishing off their African holiday with a trip to Chale Island off Kenya’s Diani Beach to deflate in the warm waters of the Indian Ocean.

We’ve just added the Mouse-Free Marion Project to our selection of trusted conservation and community projects.

We’ve just added the Mouse-Free Marion Project to our selection of trusted conservation and community projects.

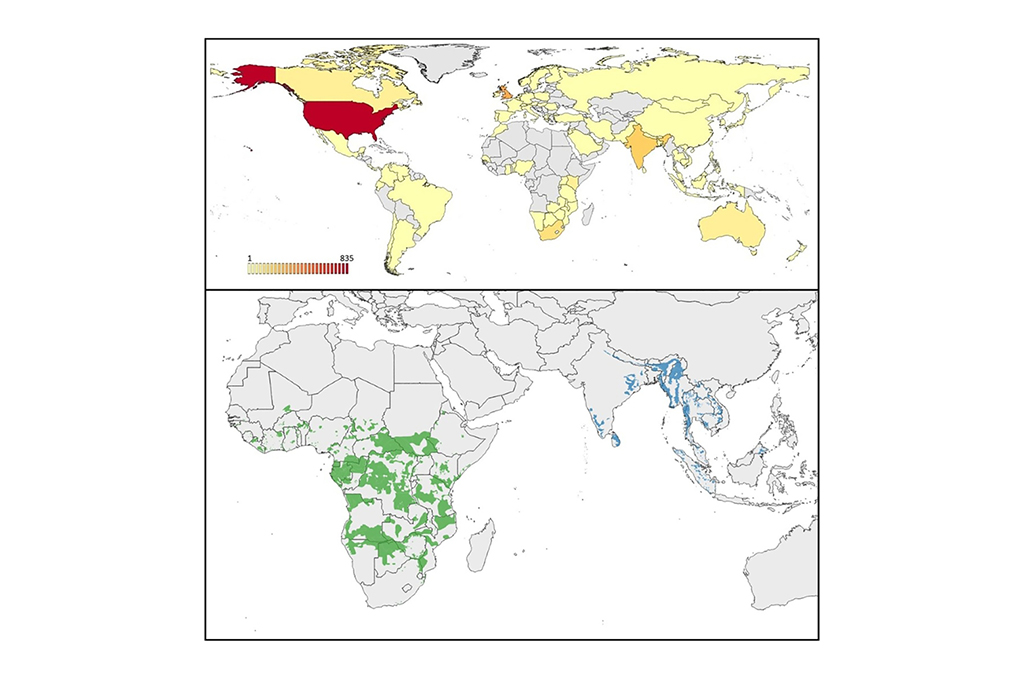

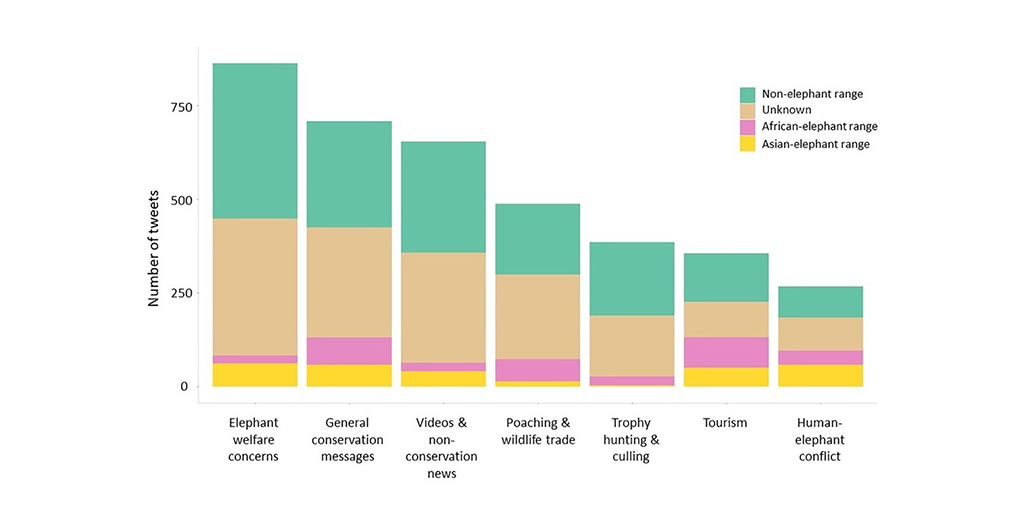

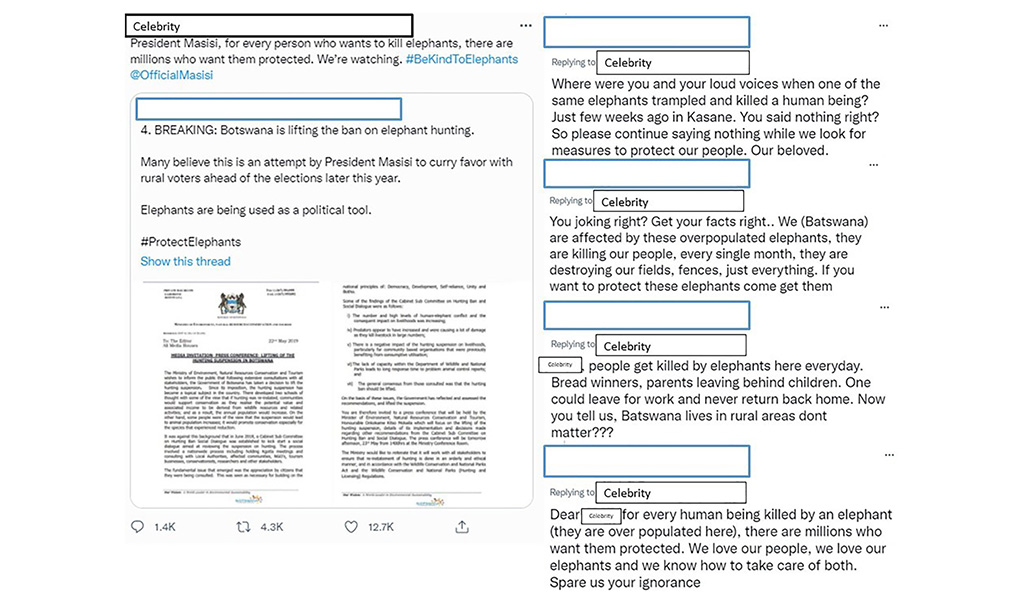

The burgeoning popularity of social media has allowed it to evolve into a potent force with positive and negative consequences. From raising awareness to the proliferation of misinformation, social media can significantly impact conservation efforts.

The burgeoning popularity of social media has allowed it to evolve into a potent force with positive and negative consequences. From raising awareness to the proliferation of misinformation, social media can significantly impact conservation efforts.

The winners of Photographer of the Year 2022 have just returned from their safari in Khwai Private Reserve, Botswana, where they stayed at Natural Selection’s

The winners of Photographer of the Year 2022 have just returned from their safari in Khwai Private Reserve, Botswana, where they stayed at Natural Selection’s

Marina Leuzinger and family

Marina Leuzinger and family

Louwhen Bowker, Care for Wild project rep, writes on the AG forum:

Louwhen Bowker, Care for Wild project rep, writes on the AG forum:

This cheetah and her cubs posed beautifully for our CEO Simon last week in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya. Simon has just returned from his safari, which was spent researching exciting destinations to add to our list of

This cheetah and her cubs posed beautifully for our CEO Simon last week in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya. Simon has just returned from his safari, which was spent researching exciting destinations to add to our list of