ANCIENT LANDSCAPE RULED BY ELEPHANTS & BAOBABS

It was pitch dark and a bit chilly as I made my way cautiously to the outside privy, scanning the inkiness with my head torch for predators and things that go bump in the night. There had been plenty of hippo and elephant activity all night, and so I was wary. And there she was, 12 paces from me, all tawny feline grace and power as she stood staring, uncertain about what to do next. I too was uncertain, and our moment of mutual fascination and frozen indecision was broken when she merged with the ink to my right – a bit close for comfort. I concluded my privy business with all senses on full alert, and retired to bed, eventually being lulled to sleep by southern ground-hornbills hooting in the distance.

The next morning I found her tracks around my hut, and those of her companion – a very large male lion. My decision to close the wrap-around fold-out cane windows at night was a good one…

This was my first visit to Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park, and I was travelling with close friends Sharon Haussmann and Dex Kotze, who also had this iconic paradise on their life lists. Guests of park management, our mission was to find out for ourselves why Gonarezhou has amassed such an ardent following as a ‘bucket-list” dream destination for experienced travellers. And, to better understand why Gonarezhou is a rising conservation success story.

Look, this is not your thing if you are into rim-flow pools and Paris-trained pastry chefs; it’s more for those of us that seek the wilderness solitude of truly wild Africa. That said, there is a luxury lodge to the north that I recommend highly – but more about that later. Accommodation within the national park ranges from rough and remote wilderness camping to very comfortable self-catering chalets, and park management is looking to invest significantly into further photographic tourism offerings inside the park.

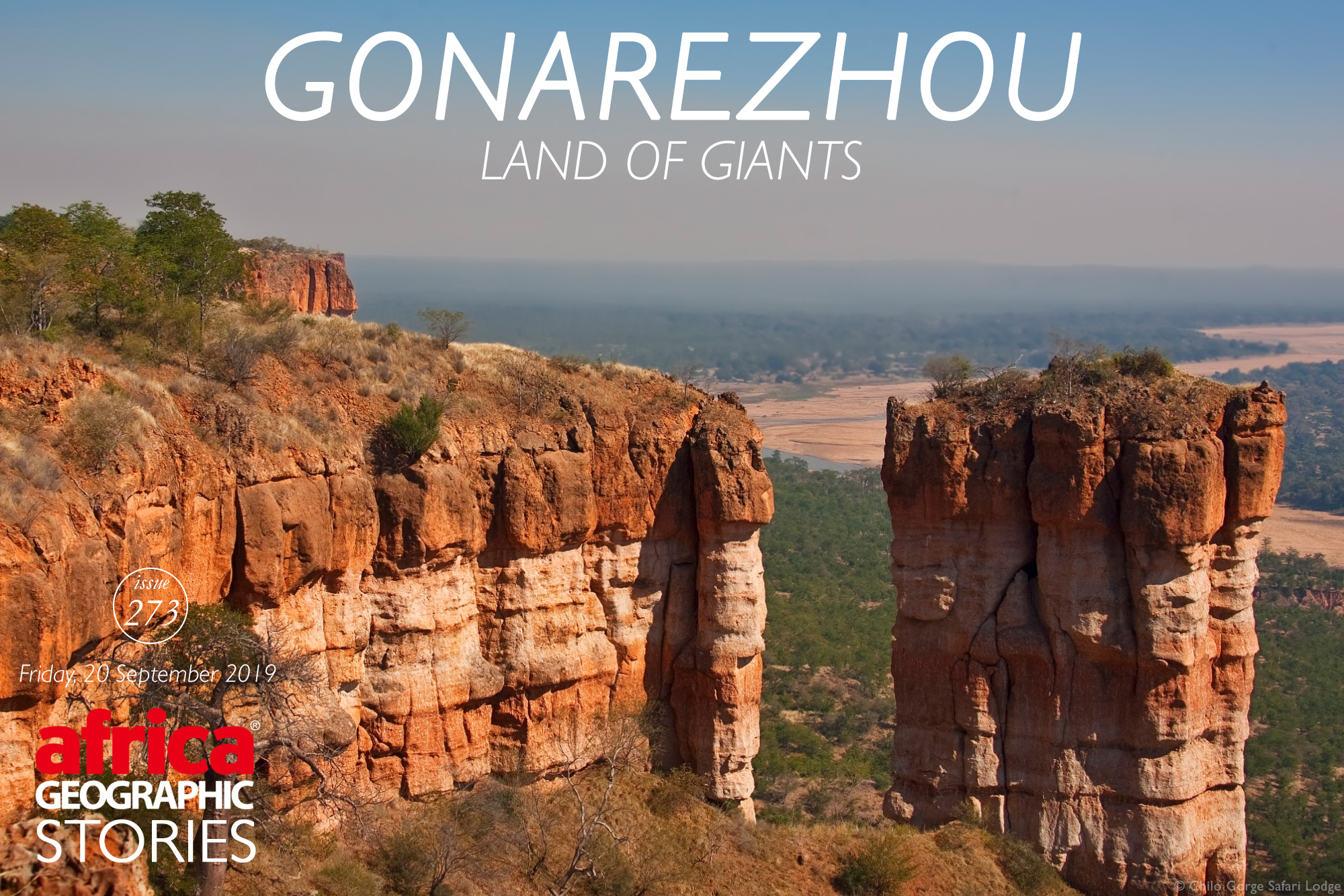

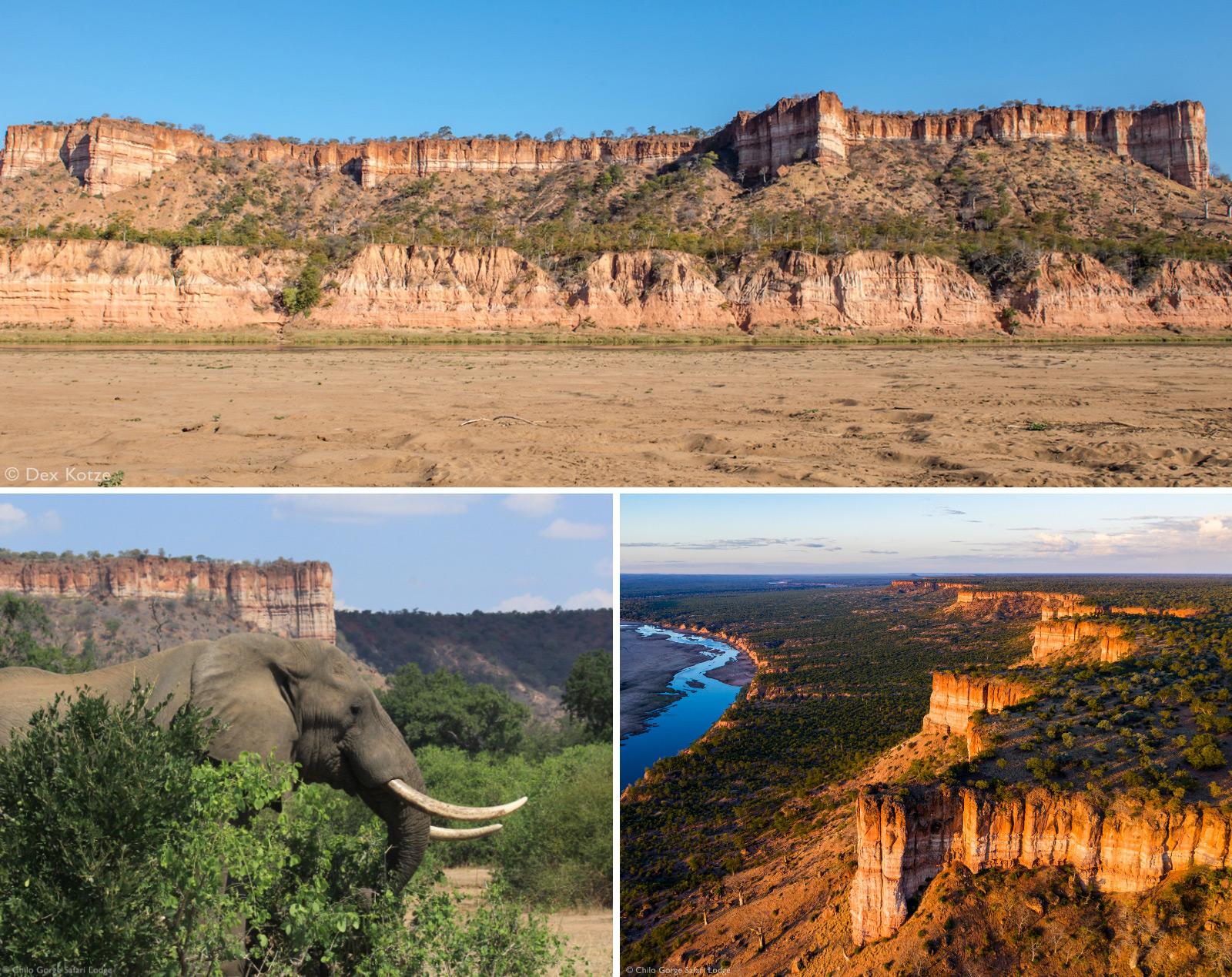

TIP: Plan to spend plenty of time at Chilojo Cliffs, to absorb the spirit of the place and to get a decent photograph. The cliffs are best photographed from mid to late afternoon, but hazy skies and long shadows can influence your photographic results. There is a long and bumpy drive to the top of the cliffs, but we opted out, deciding instead to focus on the view facing the cliffs.

We chose to drive to Gonarezhou from our homes in the Hoedspruit area, routing through the Kruger National Park, and so had the pleasure of exploring Gonarezhou on our terms. Entering the southern section of Gonarezhou via the Sango (Chicualacuala) border post between Zimbabwe and Mozambique, along the way we crossed the Limpopo River and the Lebombo Mountains. This route took us along some of the ancient migratory paths that elephants use when travelling between Kruger and Gonarezhou. There ARE more accessible ways to Gonarezhou!

Our primary reason for visiting Gonarezhou was to understand better the challenges facing elephants as they move seasonally between Kruger, Gonarezhou and protected areas in Mozambique, a passion I share with my travel companions.

SWIMUWINI CAMP

Our first stop inside the national park was in self-catering cottages at Swimuwini, a charming camp near the park’s southern HQ of Mabalauta. The old-school vibe reminded me of early-day Kruger National Park camps. Our immaculate cottage sheltered under an enormous baobab tree and commanded outstanding views over the wide and sandy Mwenezi River (called ‘Nwanetsi’ in Kruger National Park).

The river forms the southwestern border of the national park, and the 15,000-hectare community land across the river, known as ‘Malapati’, until recently used as a trophy hunting area, is now managed as part of the national park, where no hunting is permitted. This ground-breaking agreement with local communities is part of the visionary sustainable strategy for Gonarezhou National Park. Morning coffee with THAT view, as grey-headed and brown-headed parrots squawked overhead – just spectacular. Lions killed a giraffe in camp that night, and only the carcass remained…

ELEPHANTS, ELEPHANTS, ELEPHANTS

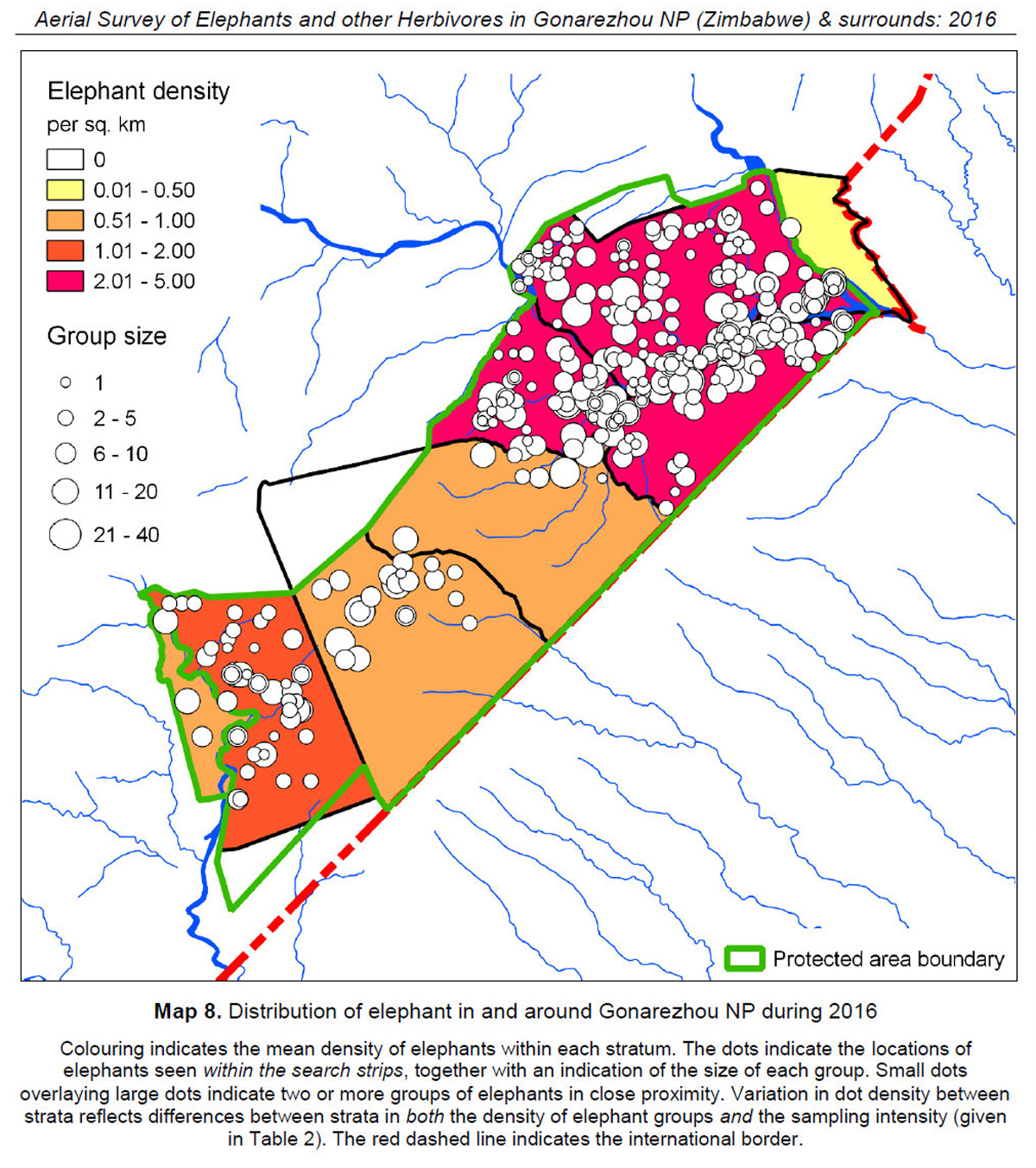

Gonarezhou is elephant country – hosting a large population of almost 11,000 pachyderms, including the largest tuskers in Zimbabwe, which are from the same genetic population as the famed large tuskers of the Kruger National Park and southern Mozambique areas. The steady increase in elephant numbers in the park is a great success story, and indicative of a well-managed protected area. BUT the convergence of elephants into a well-protected area also speaks of a bigger-picture management issue that African countries are trying to address.

Elephants used to migrate freely between Gonarezhou in Zimbabwe, Kruger National Park in South Africa and the Mozambican national parks of Limpopo, Zinave and Banhine (and other areas), in search of seasonal food and water and for mating purposes. Although some elephants do still follow these ancient migration routes, the number of migrating elephants is significantly reduced, because of human pressure and ‘fear zones’. When poachers and trophy hunters ply their sordid trade, elephants (particularly family groups) get to understand the threats, and actively avoid those areas where possible – hence the term’ fear zones’. In common with many formally protected areas, Gonarezhou is almost entirely surrounded by trophy hunting blocks.

Also, there is an ongoing tension between rural villagers living near the park and elephants, which raid crops and threaten lives. Problem-causing elephants are killed, usually by trained rangers, to protect lives and livelihoods. To better understand the difficulties faced by rural communities that live amongst elephants, please read my story Life With Elephants. As a result of these combined pressures, elephants remain primarily within the boundaries of Gonarezhou National Park for far longer than nature intended and place increased pressure on the habitat.

Throughout Africa, this is a familiar story – the concentration of elephants into areas not biologically resourced to host such large numbers throughout the year. This results in there being ‘too many elephants’ in specific areas, while Africa-wide the elephant population is being hammered by poaching.

The Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area (GLTFCA) is a visionary international drive to protect 10 million hectares (five times the size of Kruger National Park) spanning South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique – and so re-establish these natural elephant migration patterns.

MASASANI MANANGA

And on we journeyed, driving from the south through the dry deciduous woodland centre of Gonarezhou to Masasani Mananga in the north, near the main national park HQ of Chipinda Pools. The name Masasani means’ good Samaritan’, a very apt name for this rustic, off-the-grid self-catering camp. We used the camp as a base for a few days, as we were shown around the area by park management.

TOURISM AS A DRIVER OF CHANGE FOR GOOD

The footprint of Masasani Mananga camp speaks volumes for the long-term thinking going into Gonarezhou. The camp was built entirely by local women, from local material and old fence posts. The roofing thatch was purchased from villagers, who harvest the grass inside the national park – legally. Mopane saplings were used for the basic framework and rope for binding is made from ilala palm leaves. The floors are made of goat dung, and the walls are dried mud, painted with charcoal. The wall and floor cladding will require replacement after every rainy season. YES, that would be every year – because this guarantees ongoing employment and a sense of ownership. Wooden furniture is built on-site by a local cabinet-maker.

All waste is removed from the park, and the outside privy for each hut uses Enviro Loo waterless technology. The shower is inside your hut, but you have to hand-pump the water from a point next to your hut and carry it inside to fill your bucket (safari) shower. The water is gravity-fed to your unit, and heated by solar pipes.

Masasani Mananga closes for the duration of the rainy season – November to March every year. A training facility has been established in the park, to train local people for roles such as chefs and guides, to add value to tourists and entrench a sense of ownership amongst local communities. A major power line that runs through the national park is being moved out of the national park, to deliver power to nearby communities and remove an eyesore from the park – how’s that for driving change for good?

BATTLE OF THE GIANTS

Gonarezhou is undoubtedly the land of giants, and there is an ongoing battle for survival between elephants and baobab trees, although severe drought and ongoing climate change could also be playing a role. Baobabs are, in fact, succulents, and retain enormous amounts of water in their fibrous bodies – and that makes them irresistible targets for thirsty elephants (and eland and porcupine, amongst others) during dry periods. Baobabs can survive severe mauling from elephants, and will not die even if the entire tree circumference is ‘ring-barked’, but they do fall over and die once too much of the tree has been gouged away by elephants.

‘Normal’ baobab lifespans are mere guesswork – growth rings are very faint and often fade away, and so are difficult to count, but carbon dating has been done on a few individuals. The Panke Baobab in Zimbabwe (which died in 2011) was thought to be 2,500 years old, and others have been estimated at 1,000 to 2,000 years old. Usually, old baobabs die by simply crumbling into a pile of fibre, and it is speculated that years of drought in Gonarezhou and increasing regional temperatures are reducing the lifespan of baobabs. Add increased elephant pressure, and things do not look rosy for Gonarezhou’s baobabs.

Gonarezhou Conservation Trust director Hugo van der Westhuizen, who thrilled us with a flight over the northern reaches of the park, told us that Gonarezhou is losing about one baobab per week due to these combined pressures. We saw a few carcasses. I wondered what other knock-on impacts were playing themselves out below us, as we soared over this ancient landscape so defined by the two grey giants. Silent battles that we do not see or hear about on social and news media.

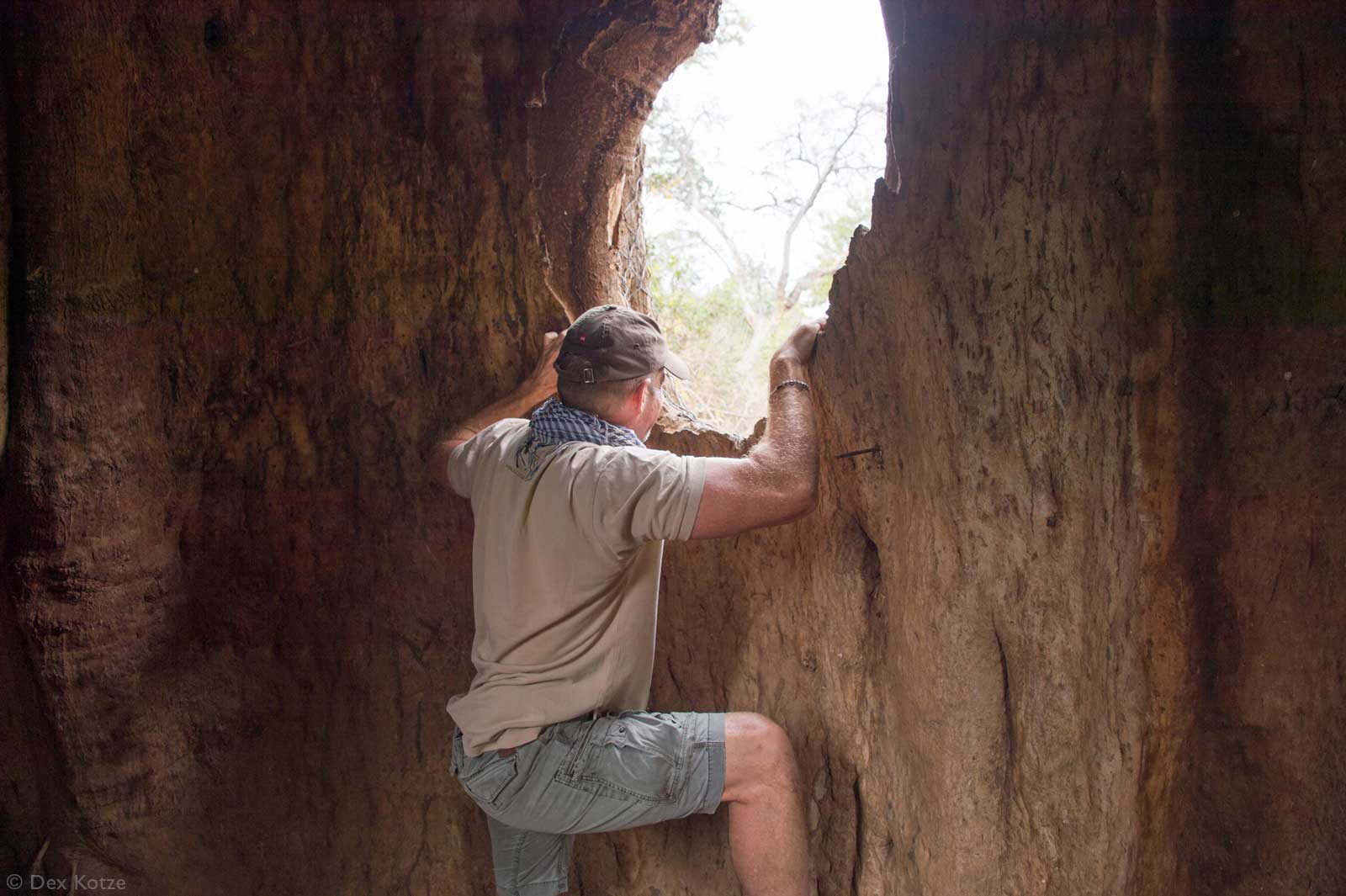

THE BAOBAB PROJECT

Although elephant impact on baobab trees and other habitats is seen as a natural process, a project to protect individual baobabs was launched in 2015. Many baobabs and other trees were lost in the drought of 1992, and elephant impact on the remaining baobab trees has been noticeable since then. Much of the damage occurs on the river floodplains, where most tourists spend their time, and the decision was made to protect trees in those areas. Methods to protect the trees include placing rocks or fallen logs around the base of trees or wrapping the trunk in wire mesh. These methods are proving to be successful, with a few exceptions.

A BIT OF LUXURY

After a few blissful days exploring north Gonarezhou with park management combined with long nights around the campfire, it was time for a bit of luxury. We fired up the wagon just after sunrise and headed northeast through the park to Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge, located on communal land on the border of the national park. The slow drive was punctuated with regular stops, to stretch the legs and to make ‘safari coffee’ – our blend of cold water and ice, coffee and Amarula (a South African cream liqueur derived from the fruit of the marula tree). We justified this decadence because elephants are known to favour the fruit and bark of the marula tree, and so our journey remained on-theme.

We enjoyed wonderful wildlife encounters during this morning sojourn, including painted wolves (African wild dogs) and plenty of elephants. We left the national park by crossing the wide Save River, and arrived at the lodge just in time for a delicious lunch, while green pigeon, trumpeter hornbill and purple-crested turaco lurked in the overhanging trees. And one of the best vistas I have seen from a lodge, in my many years of travelling Africa.

We spent two glorious days in the hands of the team at Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge and felt like family. I have heard that everyone feels like that after a spell at this delightful lodge. Our safari guide and knower-of-all-things was John Zvinashe, a local man who has a deep and insightful understanding of Gonarezhou.

Our game drives into the park were extremely enjoyable, especially so because of John’s unique understanding of this wild area. The game drive area easily accessible to Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge comprises a large area in the park known as ‘the confluence’, sandwiched between the Save and Runde rivers as they merge downstream of the lodge, with ‘Garden of Eden’ along the banks of the Save River being particularly rich in wildlife and scenic beauty.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

A quick online search will inform you that ‘Gonarezhou’ means ‘place of elephants’, but John offered a different interpretation – that this is a Shona phrase, meaning ‘horn (gona) of (re) elephants (zhou)’. He went on to explain that a powerful local sangoma (traditional healer) by the name of Khomondela used a hollow elephant tusk to administer his potions, and thus the name Gonarezhou was born. Local knowledge is always more interesting!

On the topic of names, John refers to zebras as ‘disco donkeys’ – which had us in stitches. Shout out to him for showing me my first lemon-breasted canaries and broad-tailed paradise whydahs!

THE MAN WITH GONAREZHOU SOIL IN HIS VEINS

During one outing with John, we visited conservation icon Clive Stockil, a proper legend in my circles. Clive was hosting fortunate clients at the remote Chilo Gorge Tented Camp on the bank of a wide sandy stretch of the Runde River, a more rustic option for Chilo Gorge clients. We chatted for a few hours, and I was buzzing for days afterwards. This man is the epitome of community-based conservation, a man with Gonarezhou soil in his blood.

Clive, who is a part-owner of Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge, has worked amongst the local Mahenye community for more than 40 years. The conflict between this community and wildlife escalated when they were expelled from Gonarezhou when it was declared a national park in 1975. Removal from their ancestral homeland led to a loss of that sense of ownership that is vital to keeping wildlife and ecosystems secure. They also lost their source of meat protein. Poaching was rife, as was human-wildlife conflict. Clive was requested by the government and local council members to intervene and find a solution.

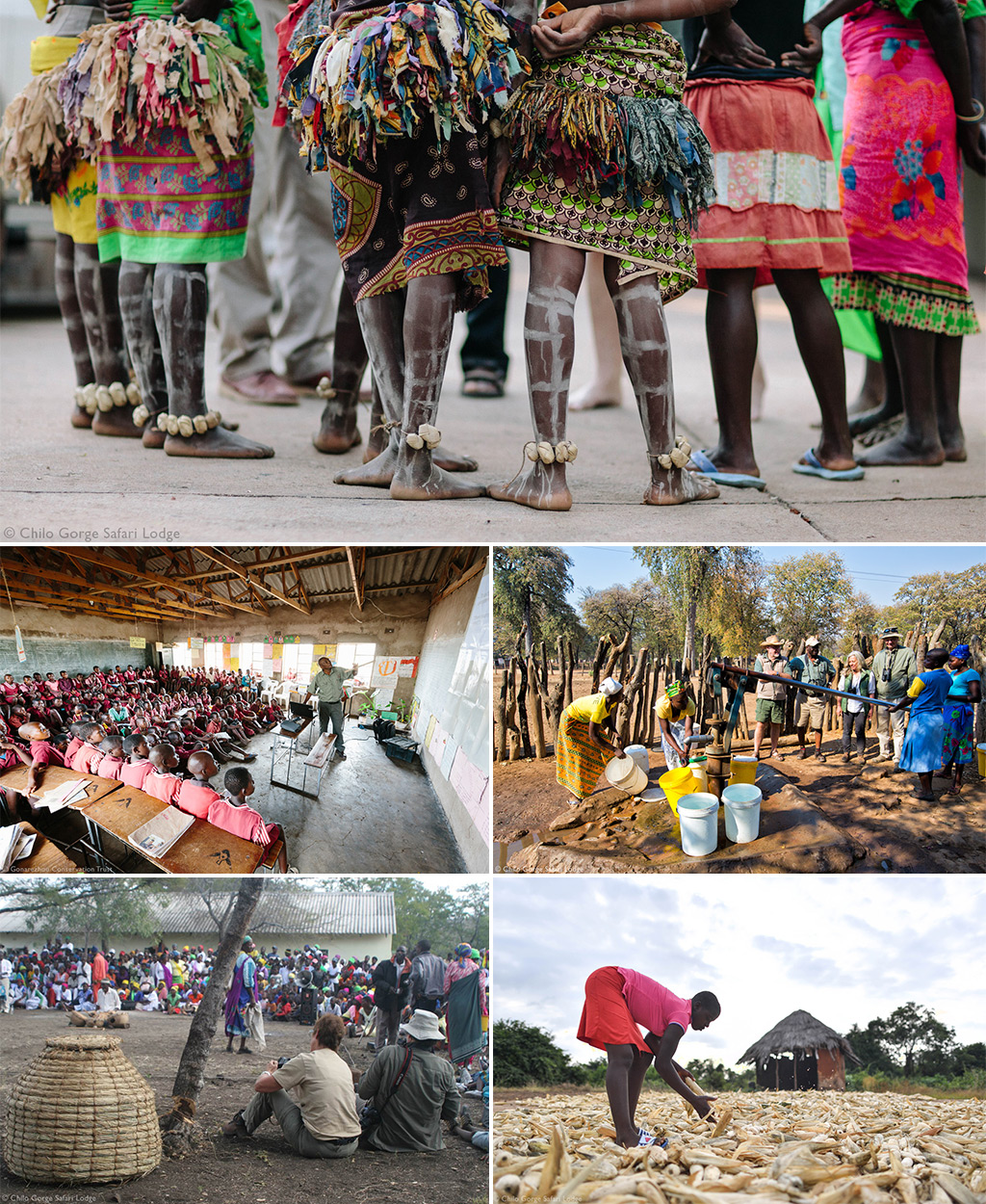

After many years of hard work and dedication, the basic principles of what would later become the highly successful CAMPFIRE project were implemented, under Clive’s direction. This project works on the ‘community-led conservation’ principle that humans will only care for wildlife if there is a benefit for them. CAMPFIRE is the acronym for “Communal Areas Management Programme For Indigenous Resources”. It empowers indigenous communities to take responsibility for sustainably managing natural resources for their benefit and to ensure the protection of the environment.

Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge was one result of that close cooperation with the Mahenye Community, who benefit from the lodge via the development of a school and guiding academy, maintenance of a clinic, and via the employment of 40 community members as lodge staff. Clive’s latest project with the Mahenye community is supported by the European Union and involves the establishment of a 7,000-hectare community-driven wildlife conservancy bordering Gonarezhou National Park.

JUST WOW

So, what do Gonarezhou elephants have in common with a fish with the shortest lifespan of all animals with a backbone – the turquoise killifish? This rather extraordinary story was told to me by Simon Capon, who manages business development in Gonarezhou, during a rather enjoyable exploration of a remote section in the north of the national park.

So, the exquisitely-named turquoise killifish Nothobranchius furzeri lives in temporary pools of water in ephemeral river systems in some semi-arid areas of Mozambique and Zimbabwe. It lives for only about nine to 10 weeks before succumbing when the water dries up and has the dubious distinction of reaching sexual maturity sooner than any other vertebrate species – at about 14 days. This fish’s eggs are adapted to last until the next rainfall event – months or years hence. Simon explained that the fish migrates downstream when the water is flowing, a good thing for genetic diversity. But how does the fish migrate upstream, to retain its distribution? This is where elephants come into the picture. Simon told me that research is underway to confirm the theory that elephants are vectors (carriers) of the eggs in their skin folds as they wander between mud wallows and tree rubs. Wow. Although not yet proven conclusively for this particular fish, this has been established for other aquatic species in this area. So, this begs the obvious question – what is happening to this fish’s range and the population now that human pressures severely restrict elephant migration?

COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT

Gonarezhou National Park has a substantial indigenous community engagement and involvement program, embracing several initiatives that include conservation education, human-wildlife conflict mitigation and general outreach programs into communities neighbouring the park. During my extensive discussions with the previously-mentioned Hugo van der Westhuizen, it became clear to me that the involvement of neighbouring communities is the cornerstone of the Gonarezhou team’s strategy. I have known Hugo for many years, and he has not changed his tune about the need to involve indigenous communities – which is possibly why this man has such a successful track record in protected area management. Click here to read more about these vital community programs. This focus on community-led conservation is shared by Clive Stockil of Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge, whose life-long commitment speaks volumes.

THE ENGINE DRIVING GONAREZHOU SUCCESS

Gonarezhou National Park is managed in its entirety by the Gonarezhou Conservation Trust team, utilising an innovative results-oriented model agreed upon between the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZPWMA) and the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS). The Trust became operational on 1 March 2017, following nine years of successful cooperation between these entities, and has a 20-year mandate. The Board of Trustees consists of equal numbers of nominees from ZPWMA and FZS.

Under this model, all cost and investment decisions are made by the Trust management team, and all revenues raised go directly to the Trust, rather than into government coffers. Revenue consists of donations and tourism proceeds, and no hunting is permitted in the national park. The 20-year plan is for Gonarezhou National Park to be financially self-sustainable, and the best tourism commercial strategy for the park is currently under deliberation and implementation.

The Trust has the experience and commitment of Evious Mpofu (Senior Area Manager) and Elias Libombo (Community Liaison Officer) in their impressive arsenal of human resources.

I have known Trust director Hugo van der Westhuizen for many years, including during his reign at North Luangwa National Park in Zambia, where his impact was also profound. He and his wife Elsabe make a formidable team. I have often referred to Hugo as the most effective protected area manager that I have met. I don’t say that lightly. Based on my more recent discussions with Trust business development manager Simon Capon, Gonarezhou is in safe commercial hands. His commercial reasoning and strategy are rock solid, and yet agile (a good thing these days). Enough said, watch this space.

ABOUT GONAREZHOU NATIONAL PARK

Description

The 5,035 km² (503,500 ha) Gonarezhou National Park lies in the southeast corner of Zimbabwe and is separated from South Africa’s Kruger National Park (2 million ha) by unfenced community land. Gonarezhou is the second-largest national park in Zimbabwe, second only to Hwange (1.5 million ha). To view and download a map of the park, click here.

Wildlife

Gonarezhou hosts 89 larger and 61 smaller mammal species, 400 bird species (plus another 92 ‘likely to occur’) and 50 fish species (including Zambezi shark and small-tooth sawfish at the confluence of the Runde and Save rivers). The park has experienced a significant increase in wildlife populations since effective management was put in place, with the latest (2016) wildlife survey of elephants and large herbivores estimating 10,715 elephant, 4,797 buffalo, 7,421 impala, 1,789 kudu, 446 giraffe, 1,830 zebra, 929 wildebeest, 241 eland and a host of other species. For a comprehensive understanding of the current populations of most herbivore species in the park, download the 2016 elephant and large herbivore survey here.

Black rhinos

Gonarezhou has twice lost its black rhino populations, with the last of the original population going extinct in the early 1940s. Seventy-seven black rhinos were introduced between 1969 and 1977, which increased to more than 100 before being wiped out by poaching in the 1990s. Editorial note: Reintroduction of black rhinos back into the park commenced in 2021.

Predators

The Gonarezhou Predator Project (GPP), established in 2009 as a collaboration with the African Wildlife Conservation Fund, monitors population trends and identifies and mitigates threats facing predators.

Historical threats to lions included over-hunting in the trophy hunting concessions around the park, retaliatory killing by livestock owners outside the park and depleted prey base. The main threat to painted wolves (African wild dogs) was a lack of prey base. To counter these threats, ZPWMA introduced a moratorium on lion trophy hunting around the park until populations recovered, and GPP introduced anti-poaching measures and human-wildlife conflict mitigation programmes. These measures have been hugely successful, with predator numbers escalating since 2009. Lion populations increased from 31 in 2009 to 181 currently, and the painted wolf population grew from a handful in 2009 to 190 now, of which 125 are adults and yearlings. Leopard, cheetah and hyena populations have also increased. Wire snares used by poachers continue to be a problem for predators, and there is an ongoing need to check painted wolves for snares.

Vegetation and landscapes

Gonarezhou’s vegetation is dominated by various types of woodlands – including alluvial, mopane, miombo, combretum, dry forests and wooded grasslands. Natural grasslands and acacia woodlands are virtually absent, and aquatic systems are limited to the three main rivers and various natural and man-made dams and pans. Baobab trees dot the landscape, towering over all other tree species. Download a 2010 vegetation study here.

Gonarezhou landscapes are dominated by impressive sandstone cliffs, various seasonal pans and the large Save, Mwenezi and Runde rivers – which feature wide beds, dense riverine forest and steep rocky gorges with waterfalls and pools. The spectacular Chilojo Cliffs on the Runde River is a much sought-after site for tourists and has become the most-photographed feature of the park.

History

The area has been protected in some form since 1934 and was declared a national park in 1975. Before that, trophy hunters plied their trade without check, and large numbers of trophy animals were hunted. Attempts by the authorities to rid the area of the tsetse fly (which affects people and cattle with nagana – sleeping sickness) resulted in vast tracts of riverine forest being ring-barked or bulldozed, natural pans filled in, fences erected, animals exterminated and pesticides sprayed.

Then, just after the area was declared a national park in 1975, civil war broke out, and soldiers treated the national park as their pantry, making snares from the fence wire. To add to the destruction, almost 10,000 elephants were culled by the authorities over 20 years, out of concern for the habitat. The national park is surrounded by trophy hunting blocks and poor communities desperate for protein. Poaching by community members using snares and poisoning used to be rife inside the park, and trophy hunters would routinely bait predators and elephants out of the park, to be shot.

Born from that cauldron of fire, present-day Gonarezhou is well-managed, with steadily-increasing wildlife populations and local community involvement. That said, the park faces enormous pressures, and strong growth in tourism support will ensure that this iconic Zimbabwean gem will survive mounting human pressures.

Tourism

The current tourism facilities inside Gonarezhou National Park are geared towards the self-catering and adventure traveller, and range from extremely remote wilderness camping sites with no facilities to comfortable fully-equipped self-catering chalets. For a comprehensive list of facilities, and to book your Gonarezhou adventure, go to this website page and to view and download a map of the park click here.

There are currently no luxury safari lodges inside the national park, but bordering the unfenced park boundary to the north is the luxurious Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge. This must-visit lodge enjoys spectacular views over the Save River and into the park and is a short game drive away from some of the best game-viewing areas in the park.

Want to go on safari? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, SIMON ESPLEY

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change’.

Image caption: Simon (left) with travel companions and photographers Sharon Haussmann and Dex Kotze

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()