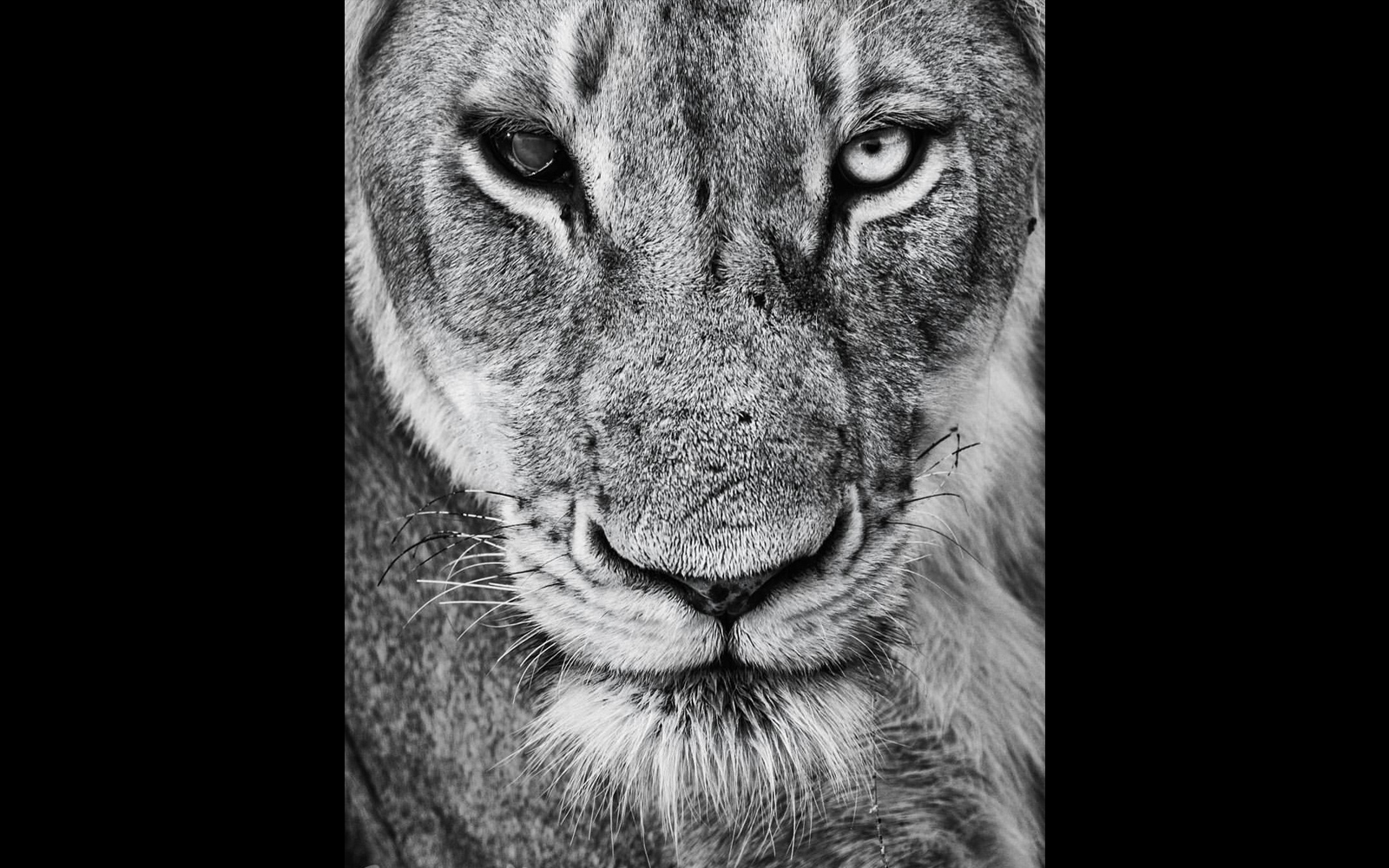

“The alpha male chimp was sitting in the forest path ahead, staring into the distance in a melancholy way as if contemplating life’s challenges, chin resting on balled fist. My party and I were waiting it out, aware that it was us who were intruding on his territory and home. He knew we were waiting because every few minutes he would glance our way disdainfully. The rest of the troop were spread about us, a fair distance away in the forest understorey, quietly relaxing and socialising. Life was good. For now.

“He then gave a heaving sigh and swaggered towards us, gangster-like. Being first in the path, I stepped aside and into the thick forest understory, holding my breath as 50kg of muscle and sinew brushed past me. And then all hell broke loose.

“With no warning or apparent reasoning, he went charging off into the forest, screaming hysterically and attacking other troop members. Chaos ensued as the entire troop erupted into a melee of gratuitous violence. Smaller chimps were flung about by their limbs and larger members charged about like hillbillies in a barroom brawl, pant-hooting and screaming at full volume. Thirty seconds later, it was all over, as the cacophony subsided into whimpers and then silence. No harm done then. My group and I were wallpaper to the drama, wary observers, ignored.

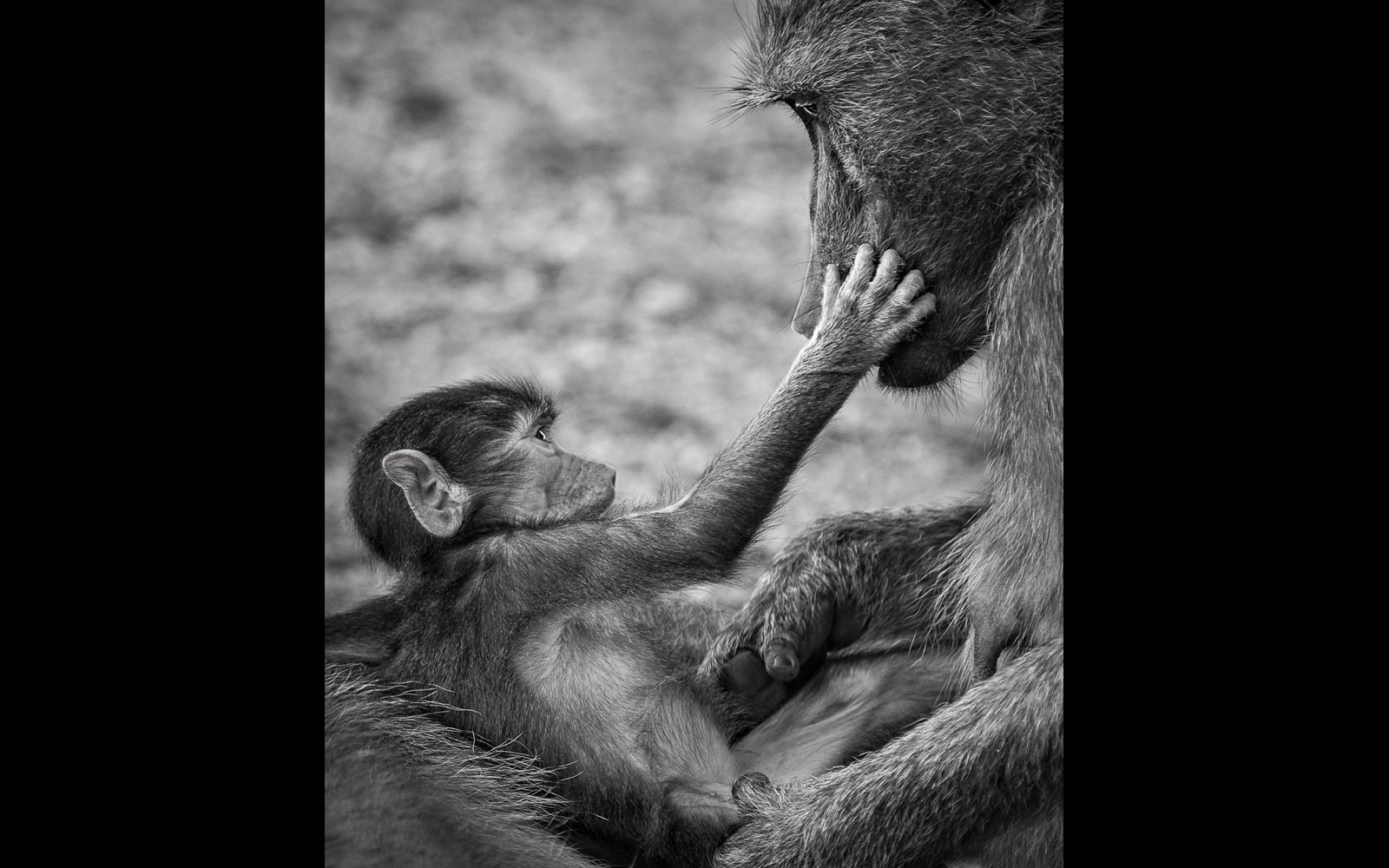

“This naked savagery was in sharp contrast to what we had witnessed the previous day. A mother was nursing a tiny infant, and this same large male approached her and tried to touch the baby. The mother slapped his hand and gave him a look that would instantly freeze boiling water. He cringed, adjusted his strategy and tried again – same result. After several attempts, she permitted a few seconds of gentle (for him) patting before nudging him aside and ambling off with her baby. The big male seemed crestfallen, confused even, as he gazed after her.

“These encounters took place in Tanzania’s Mahale Mountains National Park, and I was lucky enough to be accompanying a small party of Africa Geographic safari clients. I have encountered chimpanzees in several areas in Africa, and continue to be fascinated by them.

“The following notes, based on information provided by IUCN Red List, will provide a greater understanding as to how this magnificent creature is doing in the face of rapid population expansion of another great ape, Homo sapiens. Also, read the last section if you are keen to see chimps in the wild.”

~ Simon Espley, CEO of Africa Geographic

Brief introduction

Chimpanzees live in western and central African primary and secondary woodlands and forests, farmland and fallow oil palm plantations. They are the smallest of the great apes and our closest living relative.

They live in troops averaging 35 members (the largest known troop has 150 members). Home ranges vary – one of the smallest is 6 km² at Budongo in Uganda, and one of the largest is 72 km² at Semliki, also in Uganda.

Like humans, chimpanzees are omnivorous. They are opportunistic feeders, with fruit forming half of the diet, supplemented by leaves, stems, seeds, flowers, bark, pith, honey, mushrooms, resin, eggs, and animal prey such as insects and medium-sized mammals. They are the most carnivorous of the great apes (other than humans) and are known to form hunting parties to track down and catch species such as colobus monkeys.

Chimpanzees are proficient tool users, using sticks to extract bees, ants and termites from their nests, and stone and wooden hammers to crack nuts. They are also known to hammer tree buttress roots with sticks and their feet to communicate with other chimps.

Chimpanzees reach puberty at 7-8 years of age, and females have a 35-day reproductive cycle, commencing at 13-14 years of age, although earlier has been recorded. Chimpanzees reproduce throughout the year and have a gestation period of 230 days. Twins are occasionally born, but the norm is a single infant, and weaning is at 4-5 years of age.

A female can give birth to as many as nine infants over her lifetime and remains reproductive into her late forties. Only one-third of common chimpanzee progeny survive beyond infancy, whereas in contrast, the infant mortality rate for bonobos is low, with 73% of offspring surviving to age six. Maximum life span is unknown but thought to be about 50 years. Generation time is estimated to be 25 years.

Taxonomy

There are two chimpanzee species – the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and the bonobo or pygmy chimpanzee (Pan paniscus).

There are four subspecies of common chimpanzee, namely the Western chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus); the Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee (P. t. ellioti); the Central chimpanzee (P. t. troglodytes); and the Eastern chimpanzee (P. t. schweinfurthii). Chimpanzee taxonomy and genetics is an ongoing field of study.

Conservation status and populations

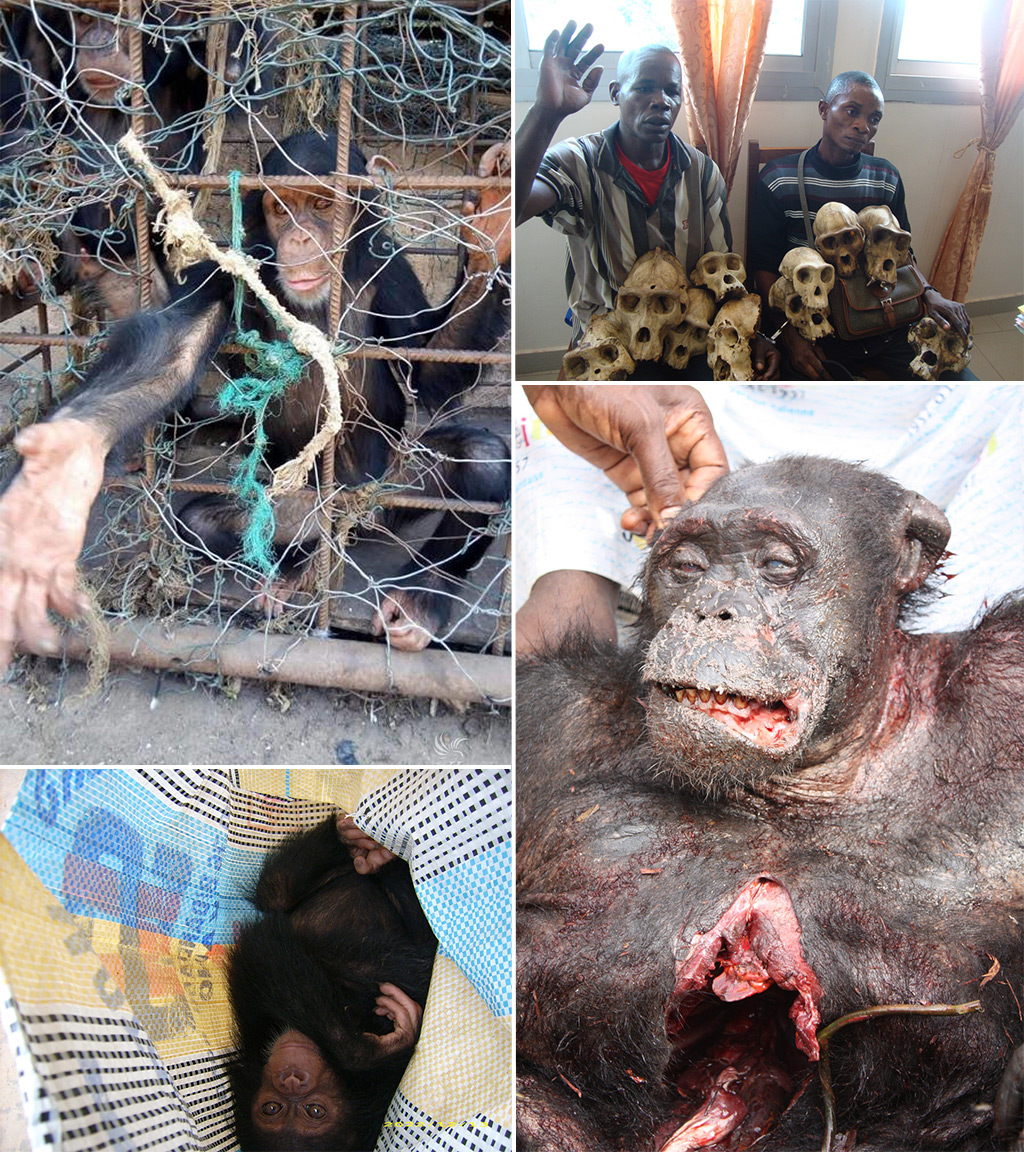

Chimpanzees are completely protected by national and international laws in all countries of their range, and it is, therefore, illegal to kill, capture or trade in live chimpanzees or their body parts. This legal standing, however, does not prevent the killing of chimpanzees throughout their ranges.

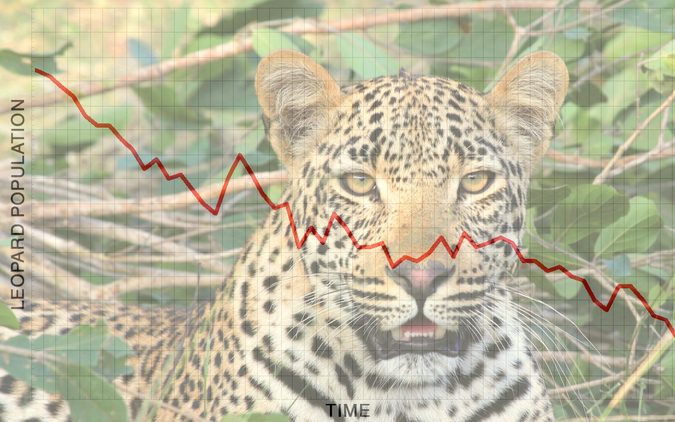

The common chimpanzee is the most abundant and widespread of the great apes (population estimate 345,000 to 470,000) and yet is classified as ‘Endangered’ on IUCN’s Red List because of high levels of poaching, infectious diseases, and loss of habitat and deterioration of habitat quality. There has been a significant population reduction in the past 20-30 years, and it is suspected that this reduction will continue for the next 30-40 years.

The estimated population reduction over three generations (75 years) from 1975 to 2050 is suspected to exceed 50%. Major risk factors include the ongoing rapid growth of human populations, poaching for bushmeat and the commercial bushmeat trade, diseases that are transferable from humans to animals (such as Ebola), the extraction industries and industrial agriculture, corruption and lack of law enforcement, lack of capacity and resources, and political instability in some range states.

• Western chimpanzee (Senegal and Ghana) – 18,000 to 65,000 individuals

• Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee (Nigeria and Cameroon) – 6,000 to 9,000 individuals

• Central chimpanzee (Cameroon and DR Congo) – 140,000 individuals

• Eastern chimpanzee (Central African Republic and DR Congo, Burundi, Rwanda, western Uganda and western Tanzania, with a small, relict population in South Sudan) – 181,000 to 256,000 individuals

The bonobo is restricted to the lowland forests of DR Congo and has a population estimated to be a minimum of 15,000 to 20,000 individuals, although only 30% of its historic range has been surveyed. Bonobos are classified as ‘Endangered’ on IUCN’s Red List because of high levels of poaching, loss of habitat and deterioration of habitat quality and diseases that are transferable from humans to animals (such as Ebola).

In some areas, local taboos against eating bonobo meat still exist, but in others, these traditions are disintegrating due to changing cultural values and population movements. There has been a significant population reduction in the past 15-20 years, and it is suspected that this reduction will continue for the next 60 years.

Major threats

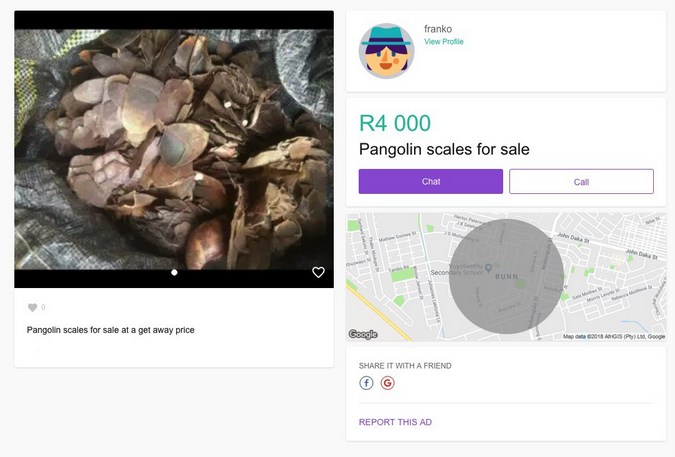

POACHING

Poaching is the greatest threat to chimpanzees, with frequent extinction occurring in entire local chimpanzee populations. Increases in human populations, easy availability of guns and ammunition, transport system efficiency, and financial incentives for supplying urban markets with bushmeat have resulted in swathes of land in the forest zone of Africa being cleared of wildlife.

Chimpanzees are generally hunted opportunistically with snares and guns but are sometimes targeted because they provide more meat than smaller mammals, such as duikers, and poisoned because they threaten local crops. Poaching is especially intense near mining sites and logging camps – where bushmeat is usually the primary source of protein available. The explosion of these extraction industries has introduced a network of roads into what were vast and roadless forest blocks. Truck drivers provide transport logistics to what has become a lucrative bushmeat industry.

Baby chimpanzees are sometimes trafficked as pets when their parents are killed for bushmeat.

HABITAT LOSS AND DEGRADATION

Subsistence/slash-and-burn agriculture

The conversion of forest to farmland across Africa has severely reduced the availability of chimpanzee habitat. Parts of West Africa had lost up to 80% of their original forest cover by the early 2000s. Extensive subsistence farming in the Albertine Rift area (eastern DR Congo, western Rwanda and western Uganda) has destroyed much of the sub-montane forest used by chimpanzees. Central Africa is experiencing lower forest cover loss.

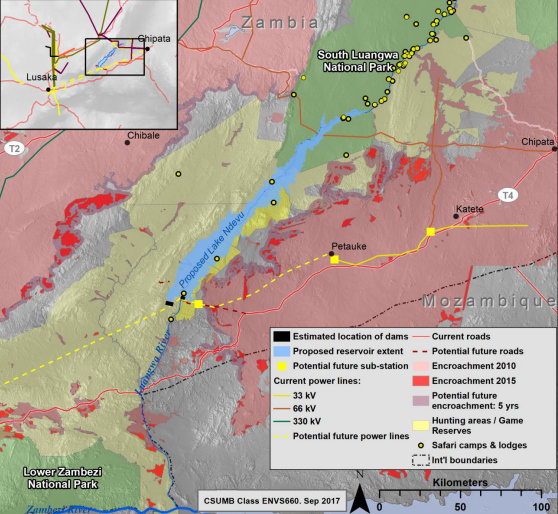

Logging, mining and oil

Timber concessions undergo removal of important food trees and resultant habitat degradation. The disturbance factor due to logging activities is also high. Mining and drilling for oil devastate wildlife habitat and lead to large-scale human settlement and the building of roads, railways and other infrastructure.

Industrial agriculture

Africa has become the new frontier for oil palm plantations, which will hit chimpanzee populations hard in coming years, because of habitat loss.

Major transportation infrastructure

Massive road projects, sometimes several kilometres wide, fragment chimpanzee habitat and enable human settlement in previously wilderness areas.

All of the above extraction industries result in habitat fragmentation due to the building of roads and introduce infrastructure and channels for the trade in wildlife products. They also cause human migration and the introduction of diseases to chimpanzees.

DISEASE

Infectious diseases that are zoonotic (transferable between humans and animals), especially Ebola, are a significant cause of great ape die-offs. Transmission between humans of Ebola is rapid, and humans are more mobile than apes, crossing large rivers and other barriers that apes do not cross – carrying the disease with them.

Because chimpanzees and humans are so similar, chimpanzees succumb to many diseases that afflict humans. Infectious diseases, including outbreaks of respiratory disease and anthrax, are the leading cause of death in several chimpanzee populations that have been habituated to human presence.

Final word

Yes, chimpanzees are under severe pressure and facing an uncertain future, mainly because of the antics of that other great ape, Homo sapiens. But there is hope because chimpanzees are a resilient species living in vast swathes of equatorial forest in the heart of Africa.

We close with a quote that reflects chimpanzees in a different light to the above scientific notes:

“In what terms should we think of these beings, nonhuman yet possessing so very many human-like characteristics? How should we treat them? Surely we should treat them with the same consideration and kindness as we show to other humans; and as we recognise human rights, so too should we recognise the rights of the great apes? Yes.” ~ Jane Goodall ![]()

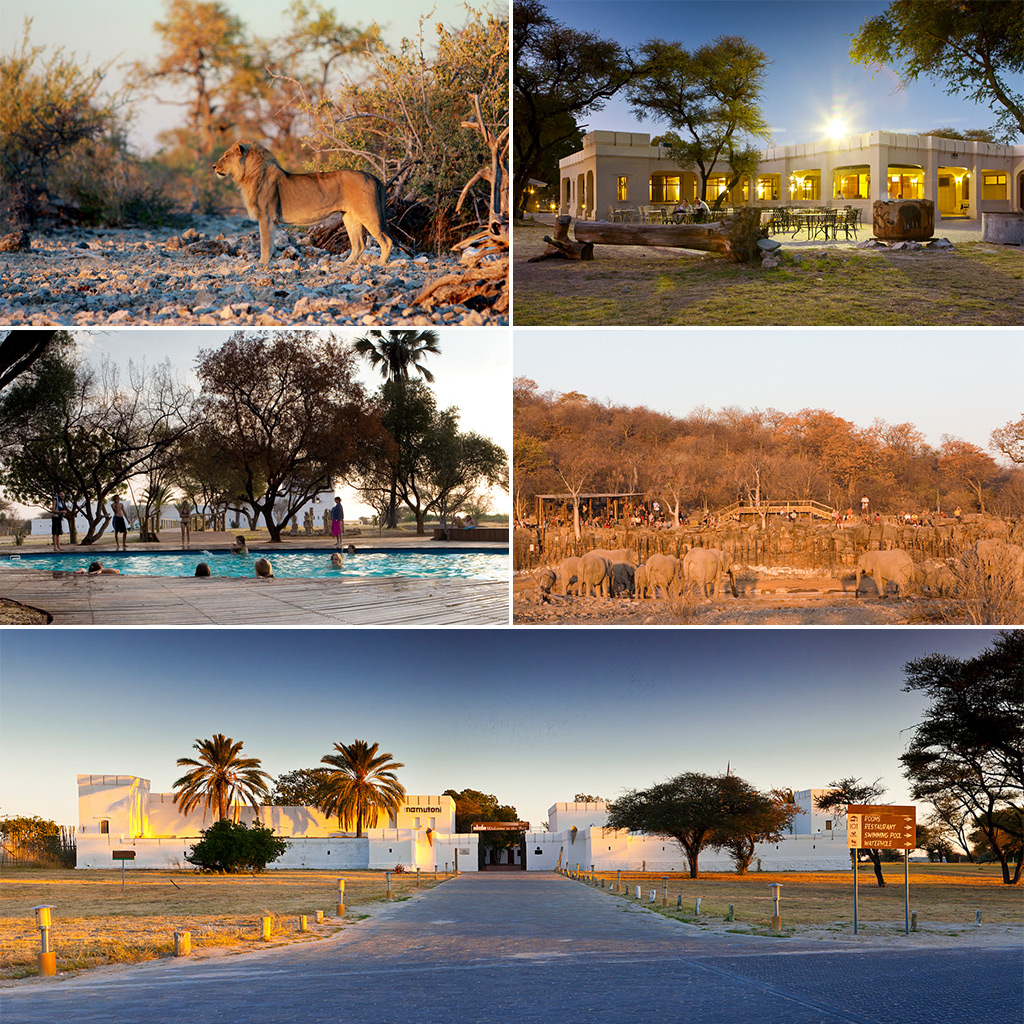

Trek for chimpanzees with Africa Geographic

There are several places in Africa to trek for chimpanzees, from the accessible highland forests of Kibale in Uganda to Rwanda’s Nyungwe, where the sheer biodiversity on offer will leave you speechless, to the remote forests of Mahale in Tanzania, where the chimps often venture onto the shores of Lake Tanganyika. Each option has its own unique appeal and other available activities. Trekking for chimps is best woven into a more extensive itinerary, due to the distances and logistics involved. Find out more about your chimpanzee trekking safari.

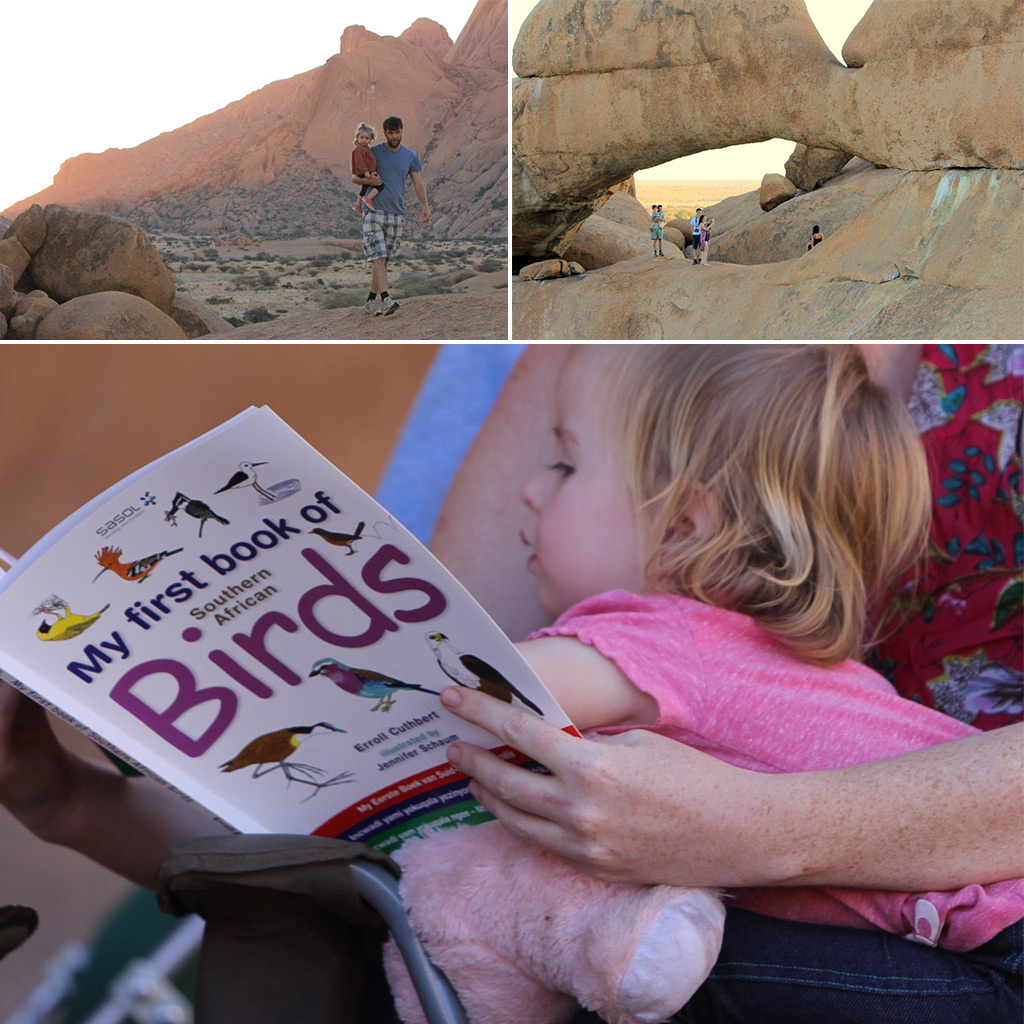

Dianne Tipping-Woods is a Hoedspruit-based journalist who tells stories about conservation, travel and development in South and southern Africa. Working for various international print and online publications, she writes about a wide range of issues and gets to explore some of the world’s most wild and beautiful places, sometimes with her two kids in tow. Endlessly inspired by the people she meets and the places she goes, every journey is a privilege and an opportunity to learn, grow and write!

Dianne Tipping-Woods is a Hoedspruit-based journalist who tells stories about conservation, travel and development in South and southern Africa. Working for various international print and online publications, she writes about a wide range of issues and gets to explore some of the world’s most wild and beautiful places, sometimes with her two kids in tow. Endlessly inspired by the people she meets and the places she goes, every journey is a privilege and an opportunity to learn, grow and write!

I am a traveller in time and space with a passion for Africa, wildlife and adventure! I was born and raised in Bulgaria, but my heart is moulded in the shape of the African continent. I came to Cape Town after I graduated with my Masters Degree in Journalism in the Netherlands and ever since day one I have been in love with the Mother City.

I am a traveller in time and space with a passion for Africa, wildlife and adventure! I was born and raised in Bulgaria, but my heart is moulded in the shape of the African continent. I came to Cape Town after I graduated with my Masters Degree in Journalism in the Netherlands and ever since day one I have been in love with the Mother City.

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in the South African Lowveld with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in the South African Lowveld with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’

April Burt

April Burt Adam Mitchell

Adam Mitchell

I was born in New York, grew up in Sweden, and am currently living in the Balkans, using it as the base for my travels around the globe.

I was born in New York, grew up in Sweden, and am currently living in the Balkans, using it as the base for my travels around the globe.