It was just before the arrival of the rains in the South African Lowveld, when the heat seems relentless. We had come across a solitary bull hippopotamus, squeezed into a tiny patch of remaining mud, the skin on his back cracked and dry. I parked the safari vehicle at a comfortable distance, observing his body language for any signs of upset, as hippos are understandably grumpy at the height of the dry season. But he could have been dead for all the movement he showed – only the slight twitches of his ears gave him away as he snoozed.

We sat for a while, contemplating the harshness of nature before I did something unfortunate. It was blazing hot, and there was not a single patch of shade. And so, I pulled out a spray-on sunscreen. Without thinking, I depressed the nozzle, and all hell broke loose…

With a sound akin to the unblocking of the world’s largest toilet, the bull extracted himself from the mud wallow and launched himself at us, mouth agape and enormous tusks front and centre. In the time it took me to start the car and throw it into reverse, he had covered the significant distance between us and was almost level with my door. I had a brief but unfortunate view of the back of his throat before I hurtled backwards up a steep slope. The bull pulled up short and shot me a rightfully affronted look. I suspect, had he been able to talk, he would have muttered some very unflattering words. To say I was decidedly rattled, deeply regretful and suitably chastened would be an understatement.

That night, the heat broke, the heavens opened, and summer rolled in on thick cumulus clouds. The bull hippo was gone the next day.

Quick introduction

I have had many other hippopotamus sightings, which have been more interesting or even more dangerous than the sunscreen incident (we were, after all, in a car and able to move away). Yet that moment still stands out in my mind as the most spectacular display of power from a hippopotamus I have witnessed – for the sheer speed with which the two-tonne bull went from dozing to full-on gallop.

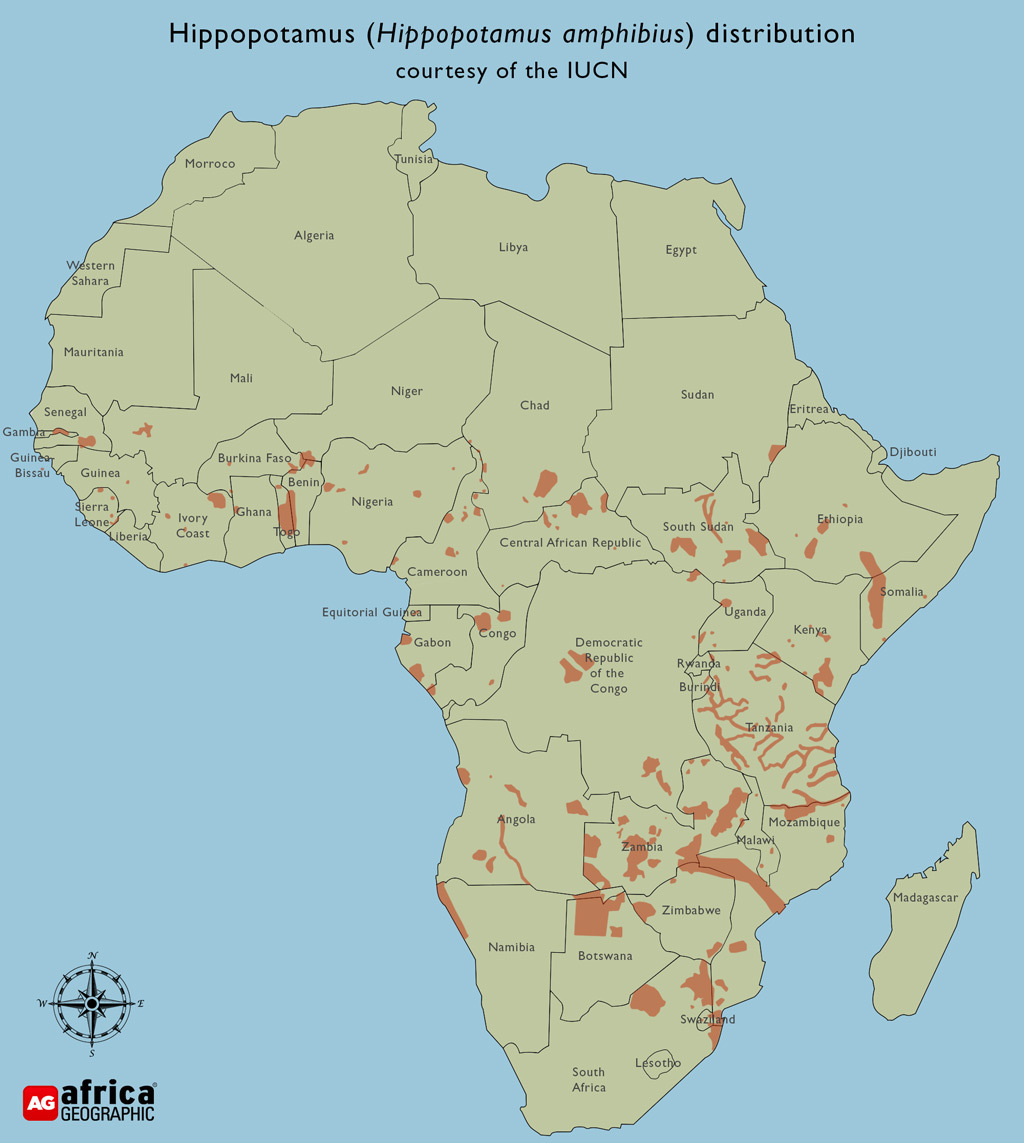

As one of the largest land mammals in the world and distributed across most of sub-Saharan Africa’s waterways, the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) probably needs little in the way of introduction. These semiaquatic behemoths prefer to spend the vast majority of their days (sometimes 16 hours or more) in the water, emerging at night or on cloudy days to graze. Despite this hydrophilic existence, hippos are surprisingly poor swimmers. They prefer to wallow in the shallows where they can stand on the river floor and move through the water by trotting or leaping along the bottom. Their dense bones confer a high specific gravity which allows them to counteract the buoyancy of the water – but this also means they cannot float.

Their specially designed skulls align the ears, eyes and nostrils on the top of the head, so these sensory organs can protrude above the surface while the hippo remains otherwise submerged. When submerged entirely, the muscles around the ears and nostrils constrict and fold to seal off to keep the water out. A hippo can hold its breath for around five minutes due to a slowed metabolism but must regularly emerge to replenish its oxygen supplies.

Though this aquatic existence confers several advantages, there is one significant trade-off: a hippo’s skin is extremely sensitive to the sun. Most people by now are familiar with the hippo’s “blood sweat” – a pinkish substance secreted onto the skin that is not blood at all but rather a specialised sunscreen. The two pigments – hipposudoric acid and norhipposudoric acid – also have antimicrobial properties to help guard the skin against infection.

Quick facts

| Mass: | Males: average 1, 500kg (up to over 3,000kg) |

| Females: average 1,300kg | |

| Shoulder height: | 1.30 – 1. 65m |

| Social structure: | Territorial males and pods of females and offspring |

| Gestation: | 243 days (eight months) |

| Life expectancy: | Up to 40 years |

| Conservation status: | Vulnerable |

Like a fish to water

The hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibious) is one of two living members of the Hippopotamidae family. The second member is the endangered pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis), native to the forests and swamps of West Africa. Several extinct members of the Hippopotamidae, some almost identical to the present-day species, once dominated the river systems across Europe and Asia (including the River Thames!). There were also at least three species of Malagasy hippos, one of which only went extinct roughly 1,000 years ago, which coincides with the arrival of humans on the island.

The hippopotamids’ closest relatives are the cetaceans – whales and dolphins. The two groups likely split from the other artiodactyls (like ruminants) around 60 million years ago and then diverged from a common semiaquatic ancestor some six million years later. The cetaceans eventually evolved to become fully aquatic, while the hippopotamids remained dependent on access to land.

Two (or more) hippos in a pod

Compared to other large land-dwelling mammals in Africa, the social interactions between hippos are challenging to study – even distinguishing young males from females is impossible when only their heads are visible. As a result, it is highly likely that there are nuances to their behaviours and social structures yet to be unravelled.

What we do know is that when water and space are plentiful, hippos form small associations of up to 15 or more individuals, known as schools, pods or, somewhat facetiously, bloats. These family groups typically consist of a territorial bull, cows, and their offspring, and mother-daughter bonds are deep-seated and may persist over a lifetime. Young males may be tolerated around the dominant bull, provided they behave submissively around him. They will often gather in small bachelor groups before eventually striking out on their own to claim a territory when they are around seven to eight years old.

Hippos do not adopt a social approach for nocturnal feeding forays, and most prefer a night of solitary snacking (where they may consume over 50kgs of grass in an evening). Interestingly, the territoriality of the bulls does not seem to extend to their land-based life, and researchers now believe that the middens are not territorial as previously thought. Male territoriality revolves around mating rights, so the region he defends in the water and along the riverbank may vary and does not extend to foraging beyond the river.

When space is at a premium (such as during the dry season when available water is limited), hippos may pack together in their hundreds. Still, they do so with seemingly great reluctance, and fights are a regular occurrence.

Frolicking hippos

Hippos may breed throughout the year, though there is usually a peak in calving during the wet season. Mating usually takes place in the water, and the female is forced to snatch quick gasps of air before the male dunks her back under the surface. Conception is followed by an eight-month gestation and the birth of a calf that may weigh up to 50kg. (It is worth considering how short this gestation period is compared to other mammals. In terms of size comparison, both rhino species give birth to calves of a similar size but their gestation period is almost double that of a hippopotamus. Even humans have a longer gestation.)

The hippo mother gives birth on her own in a quiet pool of water, and the calf instinctively strikes out for the surface immediately. The pair remain isolated until the enchanting little calf is old enough to be introduced to the rest of the pod at around a month old. As the calf grows, it becomes more confident and playful, often engaging in wrestling matches with other calves of a similar age.

Hippopotamus mothers are highly protective of their young, and hippo calves have few natural predators – generally, only lions and large spotted hyena clans attempt to hunt them. Even the massive crocodiles that share the rivers and pools are reluctant to attract maternal ire. However, one aspect of hippo behaviour that often shocks witnesses is the rare instances of infanticide. This is typically committed by the dominant bull during a territorial disruption or in times of stress, and the mother is seldom able to prevent it.

Speaking hippo

Naturally, visual communication between individuals is inevitably reasonably limited in the murky underwater environment. As a result, much hippo communication is vocal, with a laugh-like grunt being perhaps the most well-known of their vocal repertoire. However, few people realise that aside from the above surface grunts, roars, bellows and shrieks, hippos also communicate underwater. Studies show that up to 80% of hippo vocalisations are made below the surface. Some of these sub-aquatic songs are very similar to the high-pitched calls produced by whales.

Visually, the famously wide yawn is perhaps the hippo’s most notorious body language cue. The joint of the jaw is situated far back in the skull, and the orbicularis oris (the muscle we all have around our mouths) is folded in such a way in the hippo that, at full stretch, it can open its mouth almost 180 degrees. This serves to reveal an intimidating set of tusks, particularly in adult males, and should usually be interpreted as a threat display. The lower canine tusks curve upwards and can grow over 50cm in length, while the lower incisors present a forward-facing barrier of spears. The tusks are used as offensive weapons, predominantly when two bulls fight.

Fights between territorial males become more common when available water starts to shrink during the dry season. These clashes can be ferocious and fatal if one party does not back down. The vanished bull is sent packing, which, when water is scarce, can be a death sentence in the hot sun due to their sensitive skins.

The most dangerous animal in Africa?

These fearsome tusks are feared by all who encounter them, including people. The hippo is often touted as “Africa’s most dangerous animal” and the one that “kills the most people on the continent”. Both of these statements are distinctly unfair and demonstrably false. For a start (though admittedly somewhat pedantically), malaria-spreading Anopheles mosquitoes are also animals and indirectly kill up to half a million people every year. Furthermore, crocodiles likely kill just as many, if not more, people as hippos, but the bodies are frequently not found, and the victim disappears without a trace.

That said, hippos do earn their dangerous reputation. They can be aggressive and are massive, well-armed animals capable of doing significant harm. And unless you happen to be Usain Bolt, they can outrun you. Yet even this needs to be considered in context. Hippos are aquatic animals, and humans are dependent (and more populous) around water. Hippos feel safest in the water and are unlikely to bother people when fully submerged. It is when people come between them and their place of safety (or a calf) or, like my bull, during the dry season when space is at a premium, that they are most likely to attack. Staying out of their way is the best course of action. However, unfortunately, this is simply not possible for many people dependent on the river systems and living without running water.

Caught up in the tide

Of course, as dangerous as hippos can be to people, mankind too has wrought destruction on their species, and they now occupy just a fraction of their historical range. At present, the IUCN estimates there are somewhere between 115,000 and 130,000 Hippopotamus amphibius in Africa and lists their conservation status as “Vulnerable”. Though the assessors have listed the overall population trend as stable rather than decreasing, there are still many parts of Africa where hippo numbers have declined precipitously. Their close relative, the pygmy hippopotamus, is listed as “Endangered”, and there are believed to be fewer than 2,500 remaining.

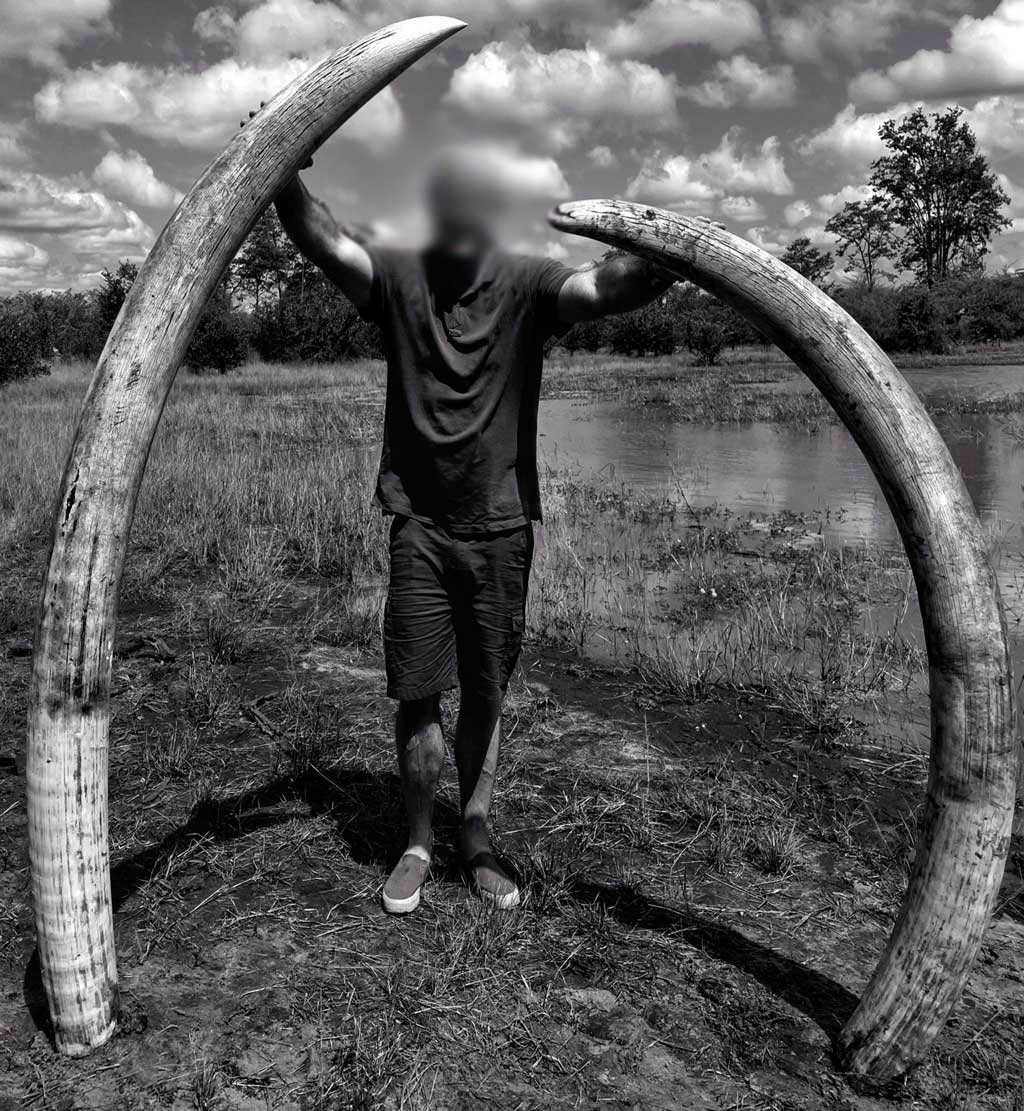

The main threats facing the hippopotamids are habitat loss (as is the case for all large African mammals) and poaching for their tusks, valued in the ivory trade. They are also frequently victims of bushmeat poaching.

Yet, like other large mammals such as elephants and rhinos, hippos are important ecosystem engineers. The copious amounts of dung flung into the water by their swishing tails (much to tourist delight) provides nutrients to the many aquatic species that inhabit the waterways of Africa. Furthermore, their movement through channels and along the riverbed helps prevent a build-up of silt and moribund material, improving the river’s flow.

The greatest of beasts

When watched from a safe and comfortable distance, hippos are fascinating and delightful animals. They are also powerful, speedy and deserving of absolute respect. From the charming little calves and placid cows to playful adolescents and awe-inspiring bulls, there is something profoundly intriguing about the knowledge that we still have so much to learn…

App subscriber Roger Whittle says:

App subscriber Roger Whittle says:

Alex Brackx is a wildlife photographer who teaches languages in Belgium. He started to pursue nature photography in 2010 while travelling in South and Central America. Through further travels in Asia, Belarus, Finland, and again South America, he began to hone his craft, travelling to film and take photos of wildlife. For Alex, it is a thrill to photograph his observations of animals, birds, landscapes, jungles, deserts and oceans.

Alex Brackx is a wildlife photographer who teaches languages in Belgium. He started to pursue nature photography in 2010 while travelling in South and Central America. Through further travels in Asia, Belarus, Finland, and again South America, he began to hone his craft, travelling to film and take photos of wildlife. For Alex, it is a thrill to photograph his observations of animals, birds, landscapes, jungles, deserts and oceans.

Geo Cloete is a multifaceted artist with a degree in architecture from Nelson Mandela Bay University. His photographic works have been recognised through various photographic competitions. Geo has completed award-winning works in architecture, jewellery, sculpture, and photography. As a life-long “aqua man” with an undying love for the ocean, it’s been his passion to share the beauty, splendour and exquisiteness of the underwater world through his photographic projects. Geo strongly believes in the notion that we only love that which we know, and we only protect that which we love. In 2016, in recognition of his contributions to ocean conservation, Geo was selected as a partner for

Geo Cloete is a multifaceted artist with a degree in architecture from Nelson Mandela Bay University. His photographic works have been recognised through various photographic competitions. Geo has completed award-winning works in architecture, jewellery, sculpture, and photography. As a life-long “aqua man” with an undying love for the ocean, it’s been his passion to share the beauty, splendour and exquisiteness of the underwater world through his photographic projects. Geo strongly believes in the notion that we only love that which we know, and we only protect that which we love. In 2016, in recognition of his contributions to ocean conservation, Geo was selected as a partner for

Cecile Terrasse is a French wildlife photographer. Cecile enjoys spending time in nature, particularly observing and photographing birds. She strives to capture beautiful light and ambience in her photographs.

Cecile Terrasse is a French wildlife photographer. Cecile enjoys spending time in nature, particularly observing and photographing birds. She strives to capture beautiful light and ambience in her photographs.

Originally from Francistown, Botswana, Brendon spent much of his childhood enjoying the outdoors. His father’s keen interest in birds and bird photography sparked Brendon’s passion for the same when he left school. This led him to pursue a degree in nature conservation. After working in a variety of southern Africa’s diverse habitats, including four years as a field guide at Phinda Private Game Reserve, he and his wife Zandri moved to the Isles of Scilly in the UK. They now spend their free time searching for rare birds and other interesting wildlife. Without large animals to distract him, Brendon is currently working on photographing the diverse moth species that the UK has to offer.

Originally from Francistown, Botswana, Brendon spent much of his childhood enjoying the outdoors. His father’s keen interest in birds and bird photography sparked Brendon’s passion for the same when he left school. This led him to pursue a degree in nature conservation. After working in a variety of southern Africa’s diverse habitats, including four years as a field guide at Phinda Private Game Reserve, he and his wife Zandri moved to the Isles of Scilly in the UK. They now spend their free time searching for rare birds and other interesting wildlife. Without large animals to distract him, Brendon is currently working on photographing the diverse moth species that the UK has to offer.

Hesté de Beer hails from a family of skilled photographers, but it was not until 12 years ago that she became interested in the craft. At the time, she asked her father to introduce her to the world of photography. He is still her mentor and strictest critic. Hesté travels with her partner to distant locations around the globe to pursue the most endangered species of the animal kingdom. Through her travels, she has witnessed the adverse effects of the ever-growing human population and technology on the natural world and ancient tribes and cultures. Hesté aims to raise awareness of this plight through her photography.

Hesté de Beer hails from a family of skilled photographers, but it was not until 12 years ago that she became interested in the craft. At the time, she asked her father to introduce her to the world of photography. He is still her mentor and strictest critic. Hesté travels with her partner to distant locations around the globe to pursue the most endangered species of the animal kingdom. Through her travels, she has witnessed the adverse effects of the ever-growing human population and technology on the natural world and ancient tribes and cultures. Hesté aims to raise awareness of this plight through her photography.

Sean Davis is an amateur nature photographer who has a passion for bird and wildlife photography. Working in the printing industry, he has always had a fascination with photography. In 2015, he accompanied a friend on an outing to photograph birds and the bug bit. Seven years on, Sean has travelled to many destinations in pursuit of honing his skill. He enjoys constantly learning from other inspiring photographers whilst photographing and experiencing the beauty of birds and nature across southern Africa.

Sean Davis is an amateur nature photographer who has a passion for bird and wildlife photography. Working in the printing industry, he has always had a fascination with photography. In 2015, he accompanied a friend on an outing to photograph birds and the bug bit. Seven years on, Sean has travelled to many destinations in pursuit of honing his skill. He enjoys constantly learning from other inspiring photographers whilst photographing and experiencing the beauty of birds and nature across southern Africa.

Nick is a wildlife guide who has been guiding for 13 years. Most of his guiding career has been spent in South Africa, where he has worked in public and private reserves. Nick has spent most of this time pursuing his greatest passion: big cats. In his spare time, he searches for big cats outside of the African continent, in destinations such as India and Brazil, searching for tigers and jaguars. For the past three years, Nick has stepped out of lodge-based guiding in favour of privately guided trips. He now travels with guests on safari trips to incredible destinations through Africa and beyond. He aims to inspire a love of wildlife through his photography and raise awareness of the importance of conservation of wild areas to make a positive impact on the world of the wild and all its inhabitants.

Nick is a wildlife guide who has been guiding for 13 years. Most of his guiding career has been spent in South Africa, where he has worked in public and private reserves. Nick has spent most of this time pursuing his greatest passion: big cats. In his spare time, he searches for big cats outside of the African continent, in destinations such as India and Brazil, searching for tigers and jaguars. For the past three years, Nick has stepped out of lodge-based guiding in favour of privately guided trips. He now travels with guests on safari trips to incredible destinations through Africa and beyond. He aims to inspire a love of wildlife through his photography and raise awareness of the importance of conservation of wild areas to make a positive impact on the world of the wild and all its inhabitants.

Kevin Dooley is an award-winning wildlife, portrait and wedding photographer who grew up in Placitas, New Mexico. His interest in photography began at an early age when at 14, he was gifted with a 35mm camera. Working as an assistant photographer and darkroom technician in his father’s portrait studio, Kevin began his life-long career in photography. After completing service in the US Navy, he returned to New Mexico and opened his photography studio in Albuquerque. During the 39 years the studio has been in operation, he has received numerous awards and been published in many publications. He has also released a photography book: Wild faces in wild places. Africa has always had a special place in Kevin’s heart. He thrives on sharing this amazing place with others.

Kevin Dooley is an award-winning wildlife, portrait and wedding photographer who grew up in Placitas, New Mexico. His interest in photography began at an early age when at 14, he was gifted with a 35mm camera. Working as an assistant photographer and darkroom technician in his father’s portrait studio, Kevin began his life-long career in photography. After completing service in the US Navy, he returned to New Mexico and opened his photography studio in Albuquerque. During the 39 years the studio has been in operation, he has received numerous awards and been published in many publications. He has also released a photography book: Wild faces in wild places. Africa has always had a special place in Kevin’s heart. He thrives on sharing this amazing place with others.

Marcus Westberg is an award-winning Swedish photographer and writer who focuses primarily on conservation topics in sub-Saharan Africa and Scandinavia. He is a photographer for African Parks, and his work is frequently found in publications such as the New York Times, Washington Post, bioGraphic, Vagabond, GEO and Wanderlust.

Marcus Westberg is an award-winning Swedish photographer and writer who focuses primarily on conservation topics in sub-Saharan Africa and Scandinavia. He is a photographer for African Parks, and his work is frequently found in publications such as the New York Times, Washington Post, bioGraphic, Vagabond, GEO and Wanderlust.

Hendri Venter is a photographic guide at Zimanga Private Game Reserve in South Africa. He has always been enchanted by wildlife and the natural world. Growing up on a farm, he enjoyed spending time with its seemingly endless expanse of wildlife. Exploring nature by horseback and by foot, he formed a strong sense of appreciation and amazement for all things natural. He enjoys taking images that capture the endless ebb and flow of nature.

Hendri Venter is a photographic guide at Zimanga Private Game Reserve in South Africa. He has always been enchanted by wildlife and the natural world. Growing up on a farm, he enjoyed spending time with its seemingly endless expanse of wildlife. Exploring nature by horseback and by foot, he formed a strong sense of appreciation and amazement for all things natural. He enjoys taking images that capture the endless ebb and flow of nature.

Aimin Chen is an independent photographer who spends much of her time focusing on field photography. Aimin has always loved the life and culture of Africa and hopes to continue to record more wonders of the world with her camera.

Aimin Chen is an independent photographer who spends much of her time focusing on field photography. Aimin has always loved the life and culture of Africa and hopes to continue to record more wonders of the world with her camera.

Guenther Kieberger hails from Austria. He picked up his passion for wildlife photography ten years ago. Working as a cameraman on wildlife documentaries, he travels to many destinations on adventures around the world. His photos have been widely published in books and magazines. His photographic pursuits centre around identifying specific wildlife subjects to capture and focusing solely on the species in question throughout a photographic trip. Sharing these images with people who cannot experience these moments for themselves brings him joy.

Guenther Kieberger hails from Austria. He picked up his passion for wildlife photography ten years ago. Working as a cameraman on wildlife documentaries, he travels to many destinations on adventures around the world. His photos have been widely published in books and magazines. His photographic pursuits centre around identifying specific wildlife subjects to capture and focusing solely on the species in question throughout a photographic trip. Sharing these images with people who cannot experience these moments for themselves brings him joy.

Jens Cullman was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1969. His introduction to photography was at age 13, when he received his first camera. As a teenager, he worked with black-and-white film and image developing until he was able to acquire more sophisticated equipment. During a trip to Namibia and Botswana in 2003, Jens’ passion for wildlife photography really ignited, and he has grown in stature since then. He has won several prestigious international awards. Jens was the winner of the Africa Geographic Photographer of the Year 2020 and a runner-up in the 2019 competition. He uses his photography to create awareness about conservation issues and preserving natural habitats.

Jens Cullman was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1969. His introduction to photography was at age 13, when he received his first camera. As a teenager, he worked with black-and-white film and image developing until he was able to acquire more sophisticated equipment. During a trip to Namibia and Botswana in 2003, Jens’ passion for wildlife photography really ignited, and he has grown in stature since then. He has won several prestigious international awards. Jens was the winner of the Africa Geographic Photographer of the Year 2020 and a runner-up in the 2019 competition. He uses his photography to create awareness about conservation issues and preserving natural habitats.

Johan, an award-winning wildlife photographer, was born in Sweden. Since 2001 he has lived on the small Mediterranean island of Malta, where he recently published his first book, on the island’s wild orchids. He regularly guides photographic tours around the world. After his first safari to Kenya in 2012, he took up wildlife photography full-time. Since then, he has had great success in prestigious international photography competitions. More recently, he was appointed as a Fellow of the Malta Institute of Professional Photography and an elected member of the Swedish Association for Nature Photographers. In his new home country of Malta, a keen interest in nature is not woven into the island’s culture, nor is it a priority in politics. With both his local and international work, Johan hopes to raise awareness and appreciation for the natural world that we are all part of.

Johan, an award-winning wildlife photographer, was born in Sweden. Since 2001 he has lived on the small Mediterranean island of Malta, where he recently published his first book, on the island’s wild orchids. He regularly guides photographic tours around the world. After his first safari to Kenya in 2012, he took up wildlife photography full-time. Since then, he has had great success in prestigious international photography competitions. More recently, he was appointed as a Fellow of the Malta Institute of Professional Photography and an elected member of the Swedish Association for Nature Photographers. In his new home country of Malta, a keen interest in nature is not woven into the island’s culture, nor is it a priority in politics. With both his local and international work, Johan hopes to raise awareness and appreciation for the natural world that we are all part of.

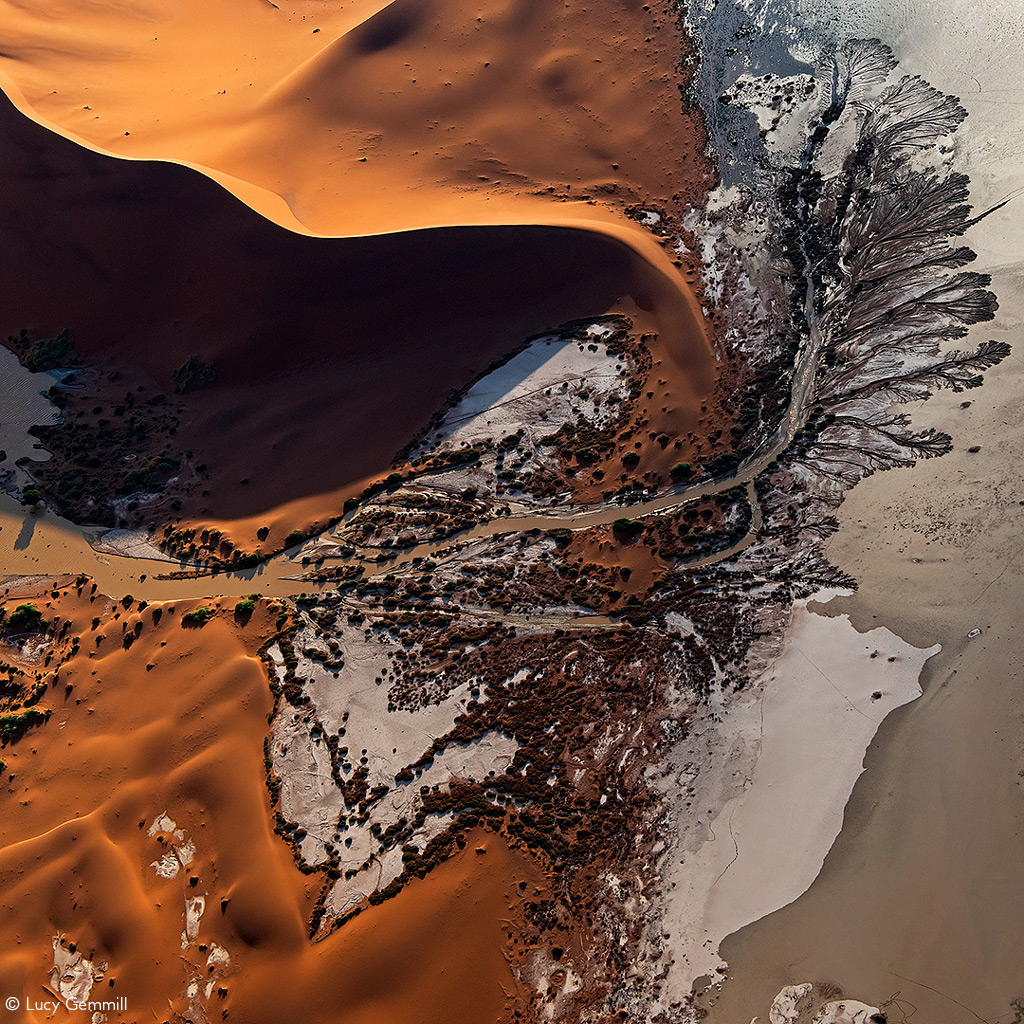

Born in San Francisco and currently based in London, Julian Asher has lived in cities around the world, including New York, Zurich, Berlin, and Cape Town. Julian is an award-winning photographer who will go to great lengths in the name of the perfect shot, including being duct-taped into a doorless helicopter over the Okavango Delta in Botswana. The risks have paid off – his work has won multiple awards and has been exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC. As a photographer, Julian focuses primarily on wildlife and wild places – with a particular interest in predators and their behaviour and in indigenous peoples and their traditions. He spends several months a year in the field in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He enjoys sharing his love of the natural world by leading photography workshops and planning safaris as the founder of Timeless Africa, a triple-bottom-line sustainable travel company. Julian serves on the boards of several Africa-focused NGOs centring on conservation and education.

Born in San Francisco and currently based in London, Julian Asher has lived in cities around the world, including New York, Zurich, Berlin, and Cape Town. Julian is an award-winning photographer who will go to great lengths in the name of the perfect shot, including being duct-taped into a doorless helicopter over the Okavango Delta in Botswana. The risks have paid off – his work has won multiple awards and has been exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC. As a photographer, Julian focuses primarily on wildlife and wild places – with a particular interest in predators and their behaviour and in indigenous peoples and their traditions. He spends several months a year in the field in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He enjoys sharing his love of the natural world by leading photography workshops and planning safaris as the founder of Timeless Africa, a triple-bottom-line sustainable travel company. Julian serves on the boards of several Africa-focused NGOs centring on conservation and education.

Owen is an aspiring conservation photographer based in South Africa, with a desire to highlight the challenges faced by tenacious peri-urban leopards in the Greater Kruger region. Owen has published a coffee table book, Searching for spots, about the leopards he has monitored through the duration of a leopard identification project he runs on Hoedspruit Wildlife Estate. His goal is to improve people’s mindsets toward human-predator co-existence and encourage the protection of the natural habitat. Although Owen has a deep love for leopards, he is a nature enthusiast who enjoys birding and the challenges that wildlife photography presents. Travelling to wild spaces and capturing unique moments is where he feels most at home.

Owen is an aspiring conservation photographer based in South Africa, with a desire to highlight the challenges faced by tenacious peri-urban leopards in the Greater Kruger region. Owen has published a coffee table book, Searching for spots, about the leopards he has monitored through the duration of a leopard identification project he runs on Hoedspruit Wildlife Estate. His goal is to improve people’s mindsets toward human-predator co-existence and encourage the protection of the natural habitat. Although Owen has a deep love for leopards, he is a nature enthusiast who enjoys birding and the challenges that wildlife photography presents. Travelling to wild spaces and capturing unique moments is where he feels most at home.

Ilna Booyens is an award-winning wildlife photographer whose work has been featured in numerous publications. She has always been drawn to the bushveld’s sights, sounds, and smells. Her passion for wildlife photography started in 2015 when she was gifted with a camera. She enjoys the connection developed with the natural world when photographing its wonders. Ilna spends as much time as possible in the bushveld, testing her patience and perseverance by braving extreme weather conditions and driving for hours to find the perfect subject.

Ilna Booyens is an award-winning wildlife photographer whose work has been featured in numerous publications. She has always been drawn to the bushveld’s sights, sounds, and smells. Her passion for wildlife photography started in 2015 when she was gifted with a camera. She enjoys the connection developed with the natural world when photographing its wonders. Ilna spends as much time as possible in the bushveld, testing her patience and perseverance by braving extreme weather conditions and driving for hours to find the perfect subject.

Want to go discover the best swimming pools while on an African safari? We have

Want to go discover the best swimming pools while on an African safari? We have