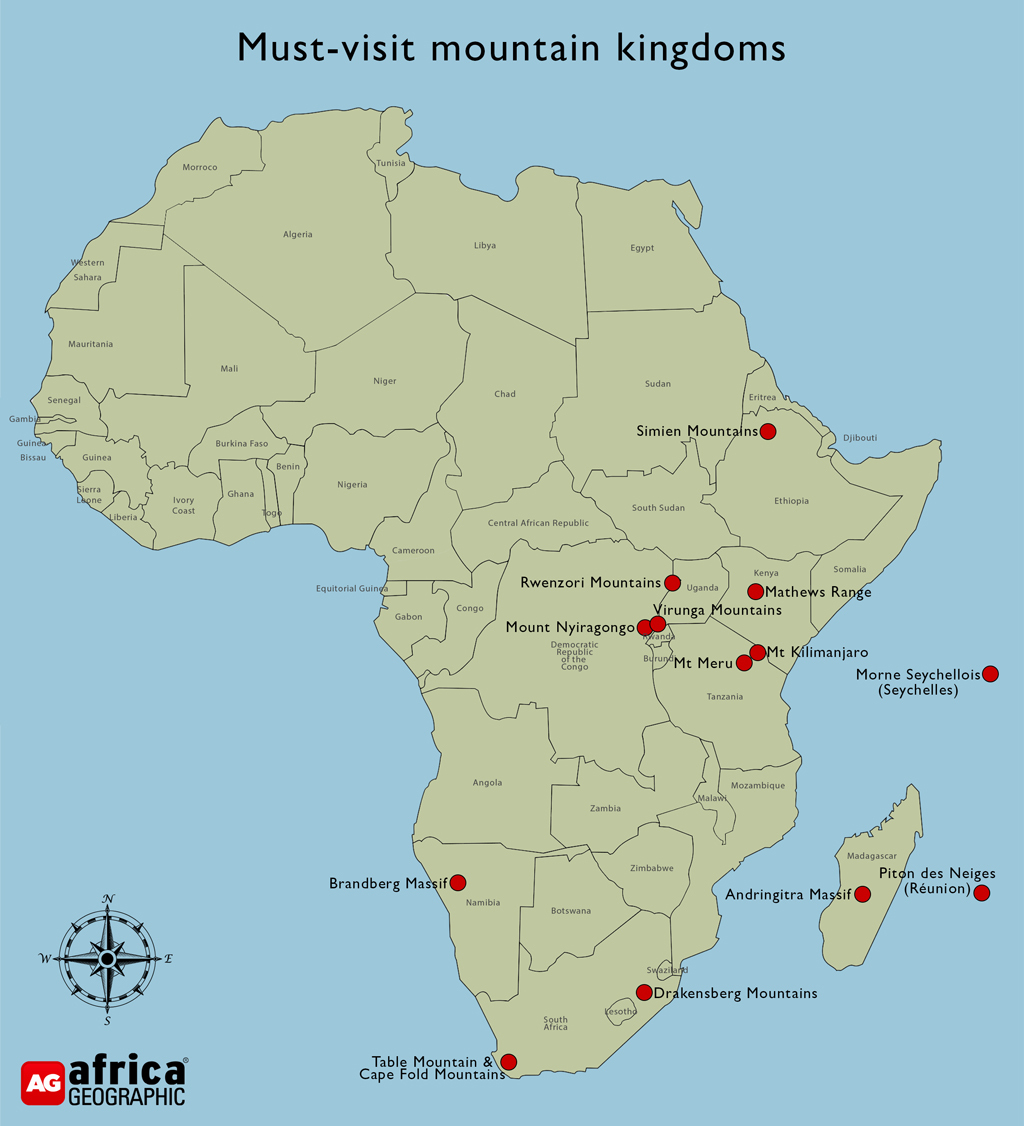

Though not everyone is a born hiker, there is no question that mountains speak to the souls of many of us. From mysterious valleys to towering peaks with panoramic views, there are mountains and massifs in Africa that are simply begging to be explored. We’ve compiled a list of our must-visit mountain kingdoms – selected for everything from their singular scenery to the creatures that call them home.

Amphitheatres, castles and cathedrals:

explore the Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa

The “mountains of dragons” reach the highest elevations in South Africa and stretch along the eastern edge of the country’s Great Escarpment, separating the fringe lowlands from the central plateau. The Tolkienesque landscape, with its vertigo-inducing rock faces and plunging gorges, is a hiker’s paradise, with a network of trails suited to every experience level. It is a land steeped in history and legend, with ancient San rock art depicting scenes of giant serpents and “eland men” and fossilised dinosaur footprints forever etched in rock.

Gorillas and montane forests of the Albertine Rift: Virunga Mountains

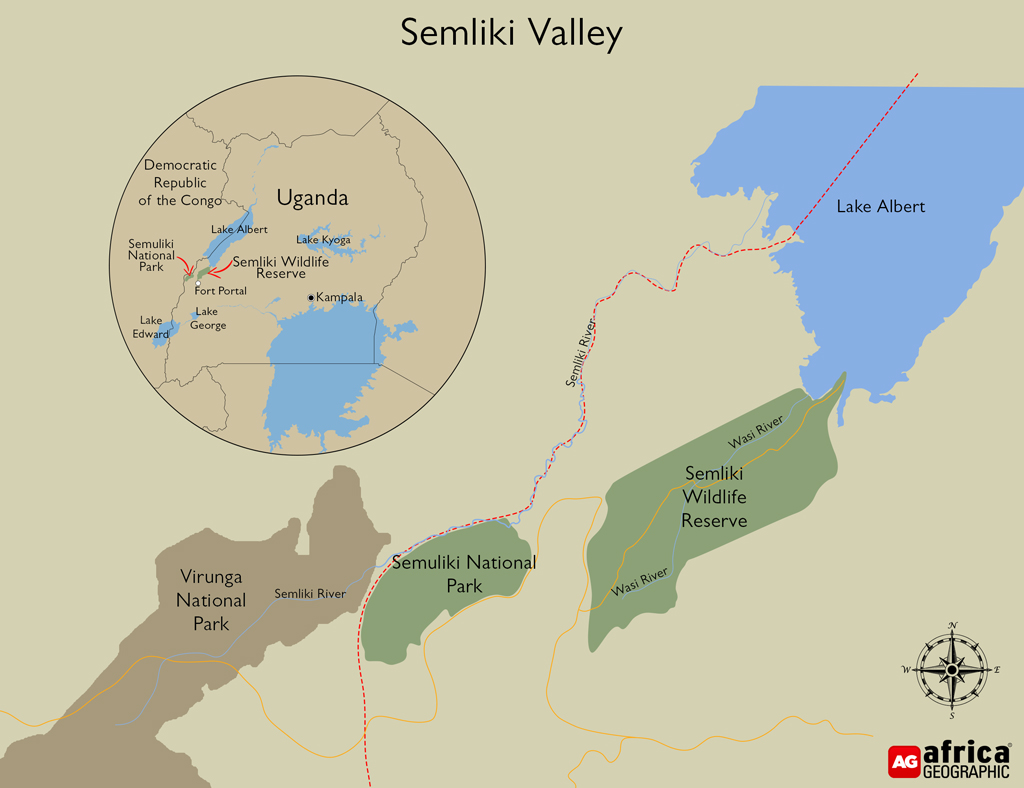

There are only two remaining populations of mountain gorillas, and, as the name implies, they survive in the cloud forests at high altitudes. Whether the search begins on the slopes of the Virunga Mountains (in either Virunga National Park, Volcanoes National Park or Mgahinga National Park – spanning Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Uganda) or within the forests of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, finding the gorillas requires a hilly ascent. These mountains are also home to many other natural and geographic treasures, including an assortment of mischievous primates and volcanic crater lakes. To find the ideal gorilla-trekking safari for you, click here.

Fire and brimstone:

look into the heart of Mt Nyiragongo, DRC

The Virunga Mountains earn their second spot on this list because two of the eight major volcanoes are still active. Mount Nyiragongo in Virunga National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo, reaches a height of over 3,000 metres, and visitors who brave the climb to the summit are rewarded with a view of the world’s largest lava lake as it churns and bubbles. This sight is most impressive at night, so most camp on the crater’s rim, braving its fury for a glimpse of life below the earth’s surface.

Follow in the footsteps of explorers:

Rwenzori Mountains of Uganda

The journey through the mystical Rwenzori Mountains begins at the terraced layers of the foothills and, for experienced climbers, continues to the snow-capped peaks of Mount Stanley at over 5000 metres. Here, alpine scenery meets tropical Africa, and climbers will move first through hardwood forest, and towering bamboo stands before reaching the alien-like vegetation of the Afro-alpine moors.

Climb to the roof of Africa in Ethiopia:

Simien Mountains

In northern Ethiopia, a spectacular massif exists where sharp crags and cliffs plunge into sweeping valleys decorated in a gentle palette of brown, green and amber. The primordial landscape of the Simien Mountains is home to some of the continent’s most unique creatures, including the Ethiopian wolf, the endemic Walia ibex and cheeky “herds” of scampering geladas. To the south, the Bale Mountains are equally enthralling, offering the opportunity to explore the fascinating alpine vegetation existing only 3,000 metres above sea level.

Summit the legends of Tanzania:

Mt Kilimanjaro and Mt Kenya

The majestic, snow-capped mountain of Mount Kilimanjaro needs little introduction, as every year, thousands of amateur and expert hikers set out to summit Africa’s highest peak. As the climb is not particularly technical, Kilimanjaro is considered one of the easiest of the world’s tallest mountains to tackle. Not far from Kilimanjaro lies its “little brother” – the dormant volcano of Mount Meru. Less crowded than the more popular Kilimanjaro, Mount Meru lies in Arusha National Park, and the trail to the summit offer hikers spectacular wildlife encounters en route up the mountain.

Explore the wilds of Kenya:

Mathew’s Range

The lush riverine valleys and forested slopes of the Mathews Range are an island of green surrounded by the red, arid lands of northern Kenya. This wonderfully remote mountain range is one of Kenya’s best-kept safari secrets. Visitors can explore the forest trails and mountain streams with local guides and encounter some of the region’s unique wildlife.

Admire the beauty of Cape Town:

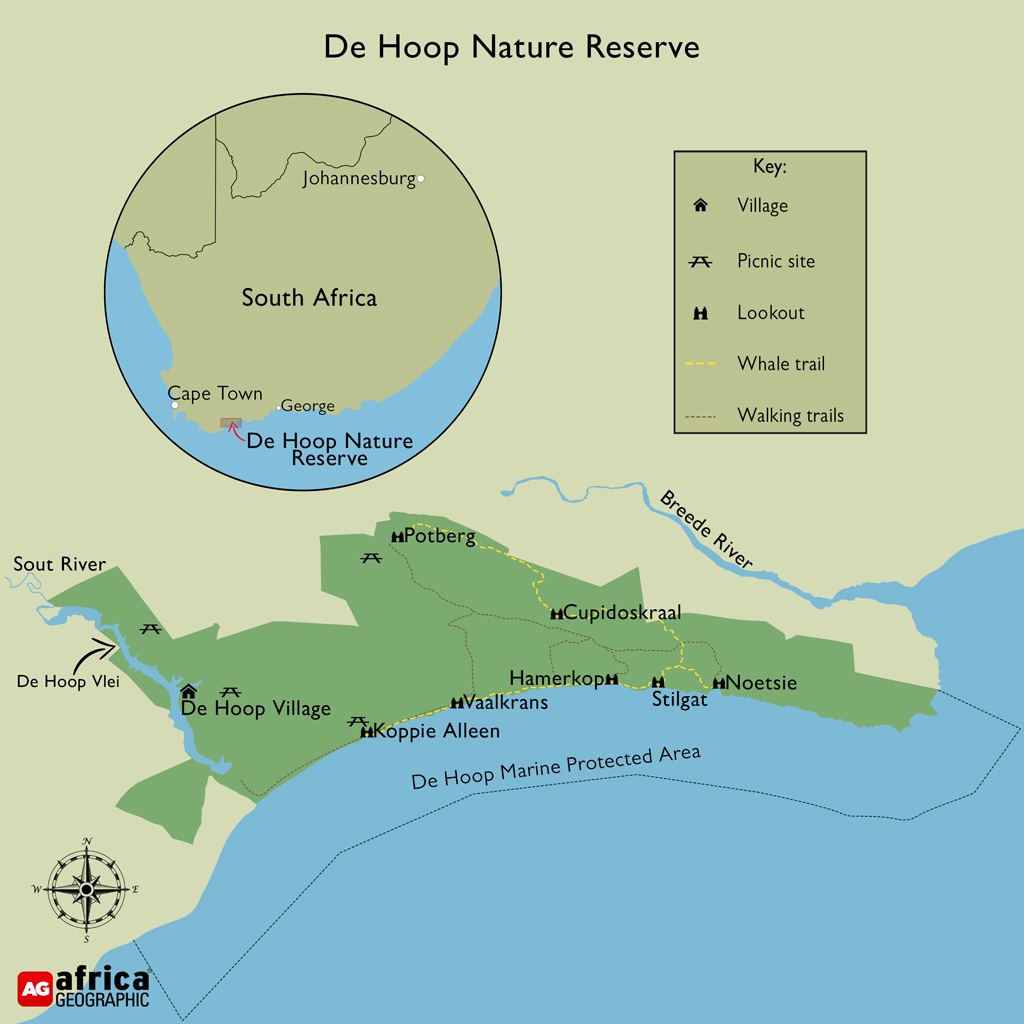

Cape Fold Mountains

Cape Town is unequivocally one of the most attractive cities in the world, nestled between the rugged Cape Fold Mountains and the Atlantic Ocean. From the iconic Table Mountain to Devil’s Peak and Lion’s Head, hiking is a popular pastime for locals and tourists alike. All are crisscrossed by a series of well-established trails which offer the chance to take in the breathtaking vistas and appreciate the unusual flora of the Cape. (And there is always the cableway for those looking for an easy route to the top of Table Mountain.)

Explore Morne Seychellois:

Mahe, Seychelles

The granite island of Mahé – the largest of the Seychelles islands – rises out of the azure Indian Ocean and continues upwards to its highest point atop Morne Seychellois. 20% of the island is covered by the Morne Seychellois National Park, where visitors can explore the mangrove swamps and jungles before climbing to the island’s highest peak to admire the extraordinary view. (Remember to keep an eye out for the elusive Seychelles scops-owl and Seychelles kestrel on the way up!)

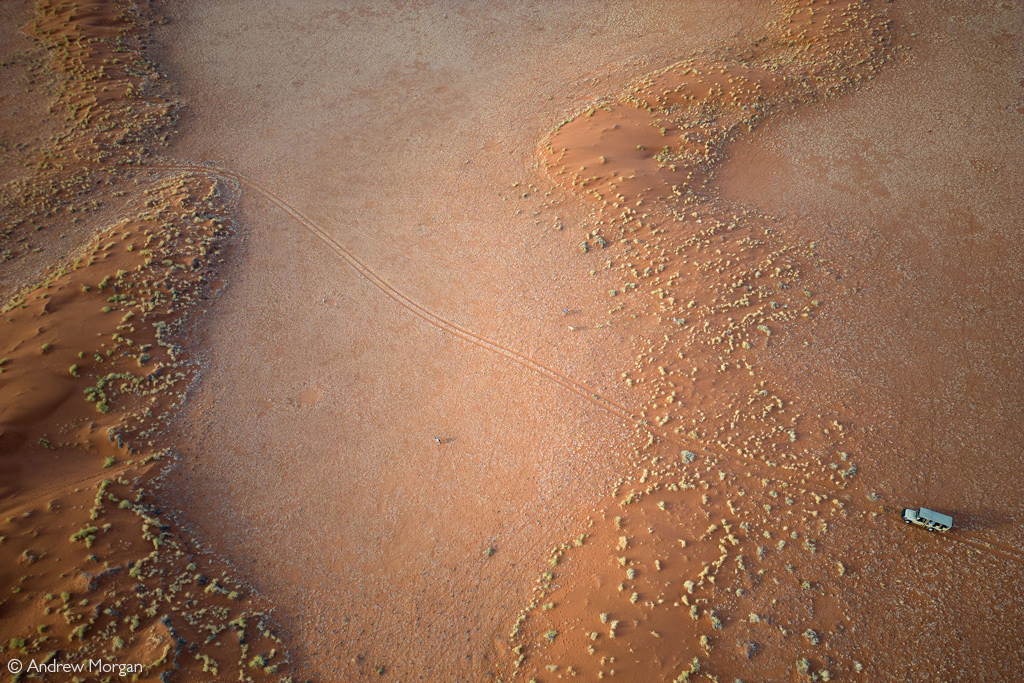

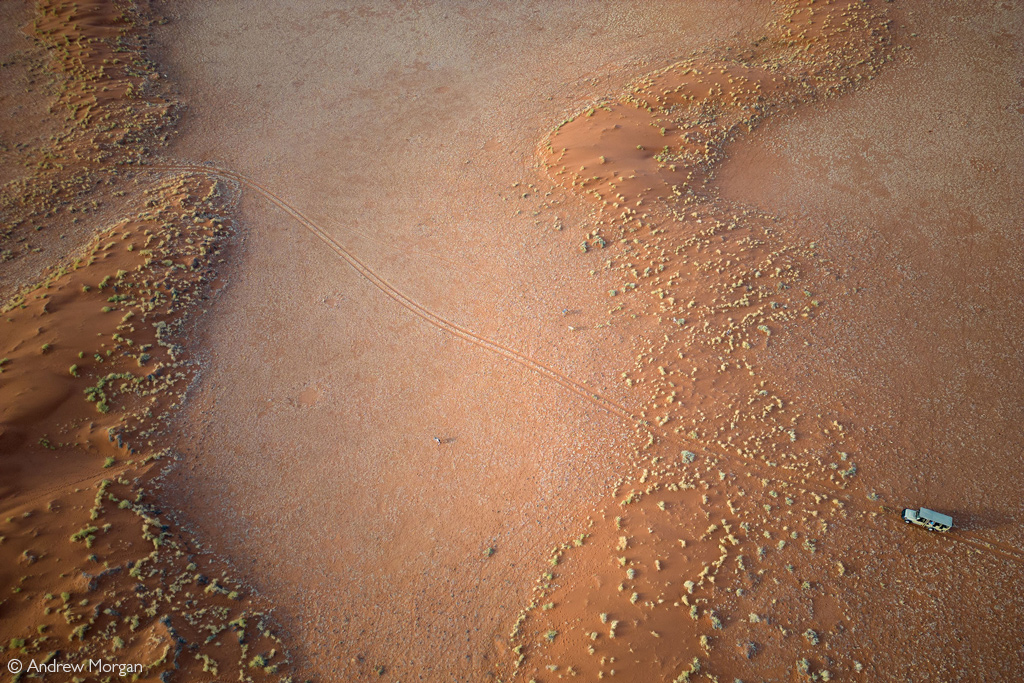

Experience ancient Namibian history:

Erongo, Brandberg Massif

In the heart of Erongo (formerly Damaraland), the granitic intrusion of the Brandberg Massif is visible for miles from the flat Namib gravel plains. It takes several days to reach the peak of Namibia’s highest mountain, which can be a hot and challenging hike. However, the effort is amply rewarded by a sense of total isolation, distinctive rock features and countless examples of ancient rock art. En-route, explore the valleys and slopes of the Erongo mountains, and the iconic wildlife found in between.

Meet the oddities of Madagascar:

the Andringitra Massif

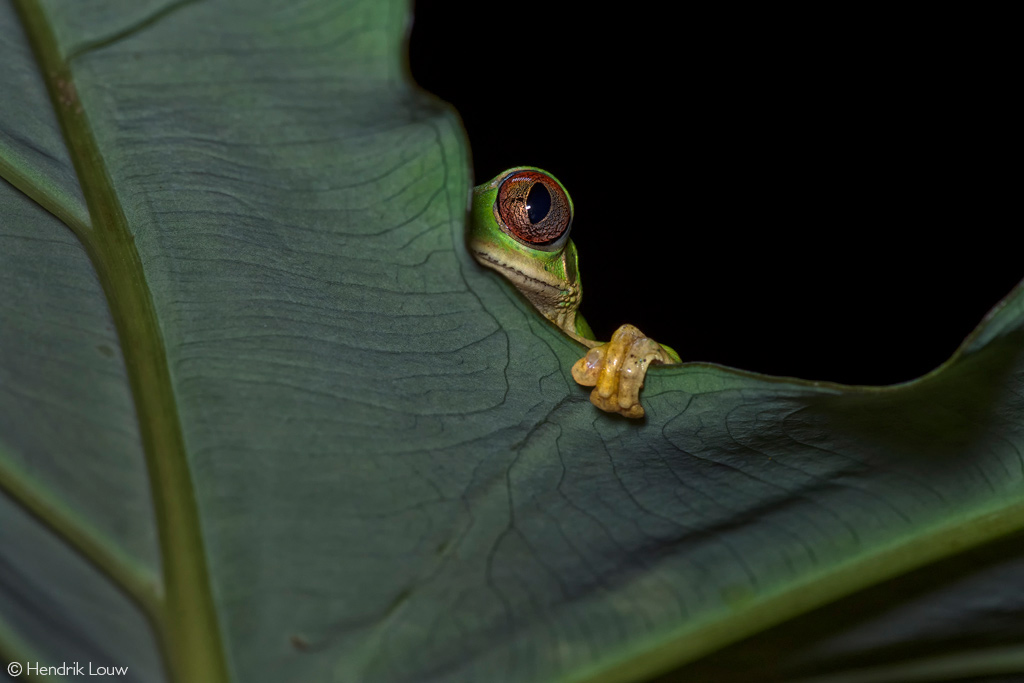

The Andringitra Massif is one of Madagascar’s most popular hiking destinations and is considered one of the island’s most biologically diverse regions. Away from the sharp cliffs offering impressive views of the plains below, moist tropical forests on the eastern flanks and dry forests on the west support a wide variety of endemic life, including 13 different lemur species.

Visit a shield volcano on a tropical island:

Piton des Neiges, Réunion

While Réunion is known more as a tropical beach paradise than a hiking destination, it is home to the highest mountain in the Indian Ocean – Piton des Neiges – which reaches over 3,000 metres above sea level. The park’s volcanic landscape is a designated World Heritage Site. The somewhat challenging hike to the summit is usually broken into two days, with many hikers rising early on the second day to watch the sunrise from the peak.

* Note: Due to political instability in parts of Ethiopia and DRC, travel advisories may be in place. Chat to our safari experts for guidance – see details below this story.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

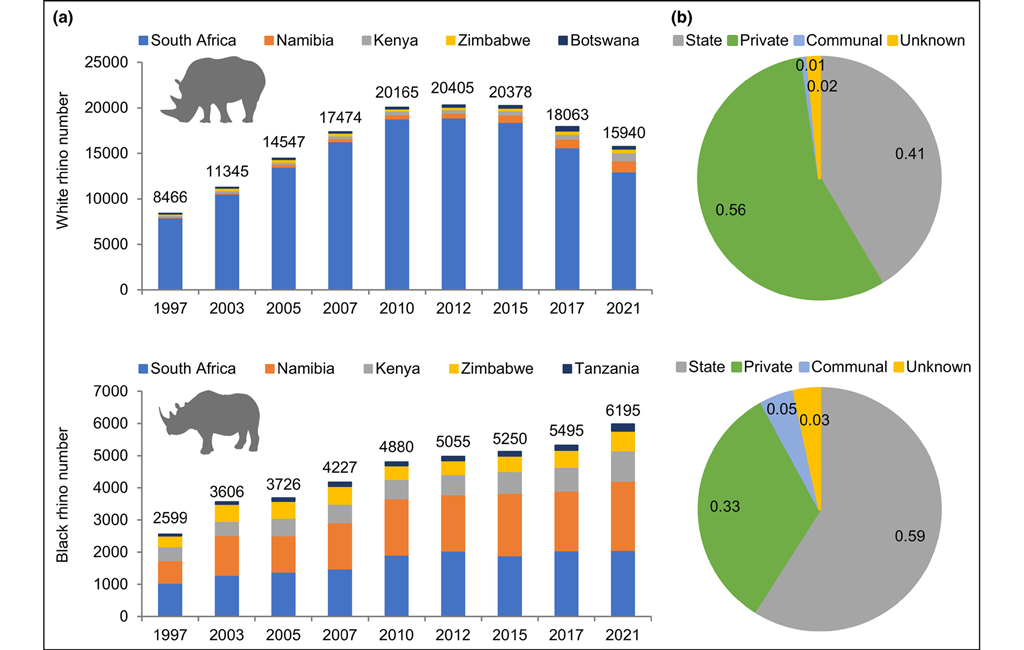

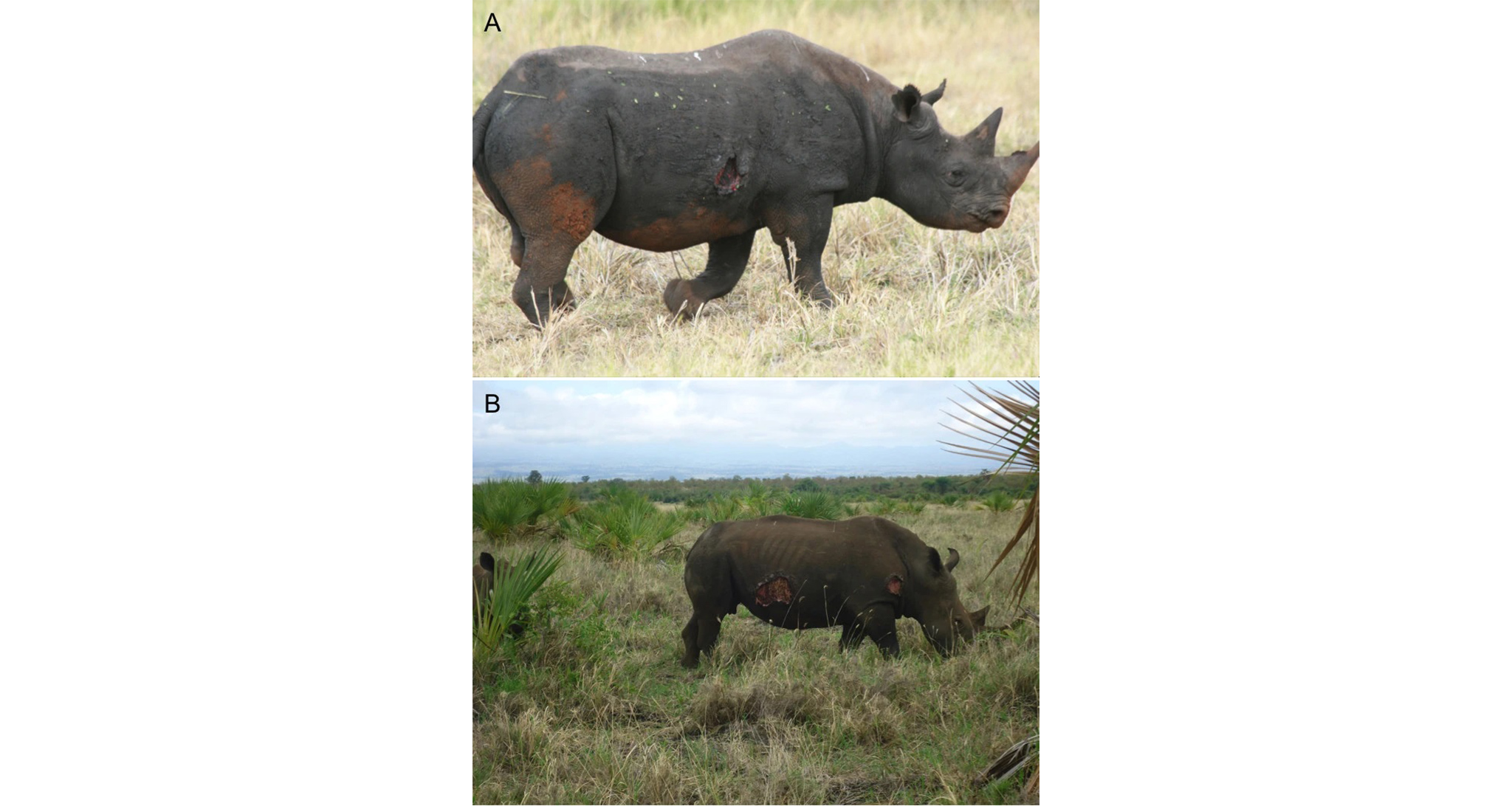

Private landowners in South Africa now collectively support the largest population of white rhinos on the African continent. More than half of the continent’s rhinos are in private hands. This was the inevitable outcome of declining wild populations and increasing numbers of rhino found on private land. It brings into stark relief the importance of the private sector in rhino conservation. Given the rising costs associated with protecting rhinos, what will it take to build resilience in the private industry?

Private landowners in South Africa now collectively support the largest population of white rhinos on the African continent. More than half of the continent’s rhinos are in private hands. This was the inevitable outcome of declining wild populations and increasing numbers of rhino found on private land. It brings into stark relief the importance of the private sector in rhino conservation. Given the rising costs associated with protecting rhinos, what will it take to build resilience in the private industry?