One of Aesop’s fables tells of a vixen taking her numerous pups out for an airing. She comes across a lioness proudly carrying a single cub. ‘Why such airs, haughty dame, over one solitary cub?’ sneers the vixen. ‘Look at my healthy and numerous litter here, and imagine, if you are able, how a proud mother should feel.’ The lioness lifts her nose and says, ‘Yes. I’ve only one. But remember, that one is a lion.’

Haughty indeed, but such is the hierarchy of the wild. Most recently, a dog named Vixen had a more violent confrontation with a lioness. In this case, Aesop’s fable would be overturned for honour favours the dog. She was a rare East German shepherd. Her back was straighter, and her temperament more persistent and alert than the common German shepherd. She was trained to track and apprehend poachers on a private game reserve bordering the Kruger National Park and worked alongside her devoted handler Jonas, who also happens to be a pastor.

After a night patrol, Jonas was driving back with Vixen at his side. It was one of their last patrols together before she was to be put into a breeding programme. Jonas stopped at the game reserve gate and talked with the gate guards.

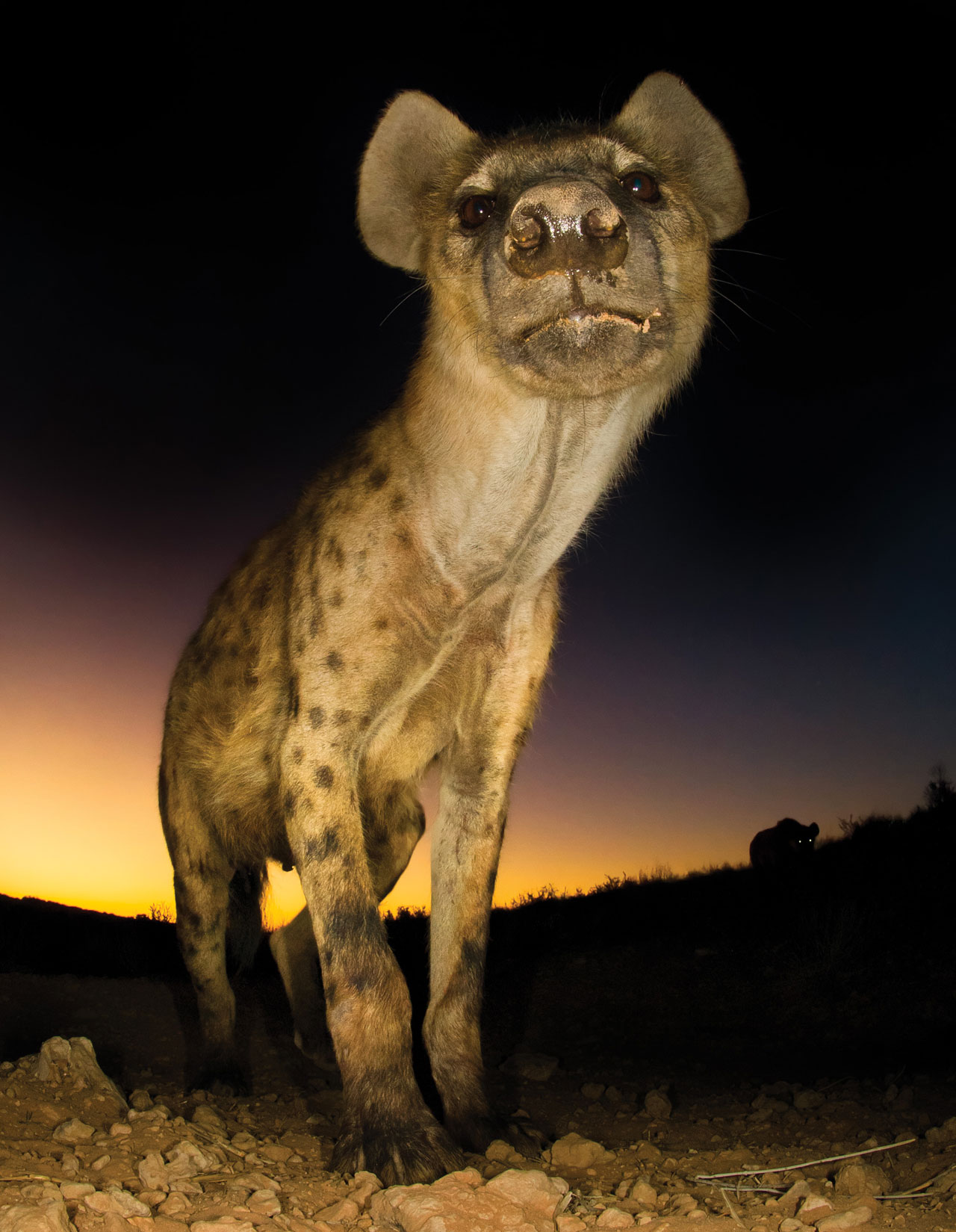

The lioness became aware of Jonas as he left the vehicle

An injured lioness that had been displaced from her pride was lurking nearby. She’d been drawn to the light of the guard hut and the smell of food from the nearby community. There, skinny and starving, she had watched the guards and contemplated an easy meal. She became aware of Jonas as he left the vehicle. And Vixen became aware of her.

Vixen immediately put herself between Jonas and the beast. The lioness attacked classically, clamping her jaws around Vixen’s throat and suffocating her.

There was little Jonas could do but call for backup. As the hungry lioness fed on Vixen’s hindquarters, the K9 team tried to force her off by advancing toward her with the vehicle. Finally, they poured water on the lioness – for there are few things a cat hates more – and she ran off, leaving them time to recover Vixen’s body.

Jonas owes Vixen his life. She was buried at her home and training facility. Flowers were laid on her grave, and Pastor Jonas led the ceremony.

©K9 Conservation

Since the first canid tentatively accepted food from a human, dogs have been an integral part of our lives. Our best friend, protecting and serving, often just loving. By our hands, many dogs have had the wild bred out of them. But the most progressive step in our manipulation of the dog is to rekindle their friendship with the wild. In essence, dogs like Vixen now play a role in protecting endangered species, even lions.

K9 Conservation has been operating since 2011 and has more than ten such dogs working on game reserves near Kruger National Park, a region that has seen some of the worst rhino poachings in Africa. As well as German shepherds, they work with and train weimaraners and Belgian malinois. Weimaraners are 300-year-old German dogs bred for tracking and hunting stag and other large game. Their refined hunting instincts enable them to be essential in locating animals injured or killed by poachers. This complements the malinois’ more aggressive nature, endurance, agility and superior skill in tracking humans, so the two breeds are often used in tandem. When a poached animal is located by the weimaraner the malinois takes over, picking up the scent of the poachers so tracking and apprehension of the culprits can begin.

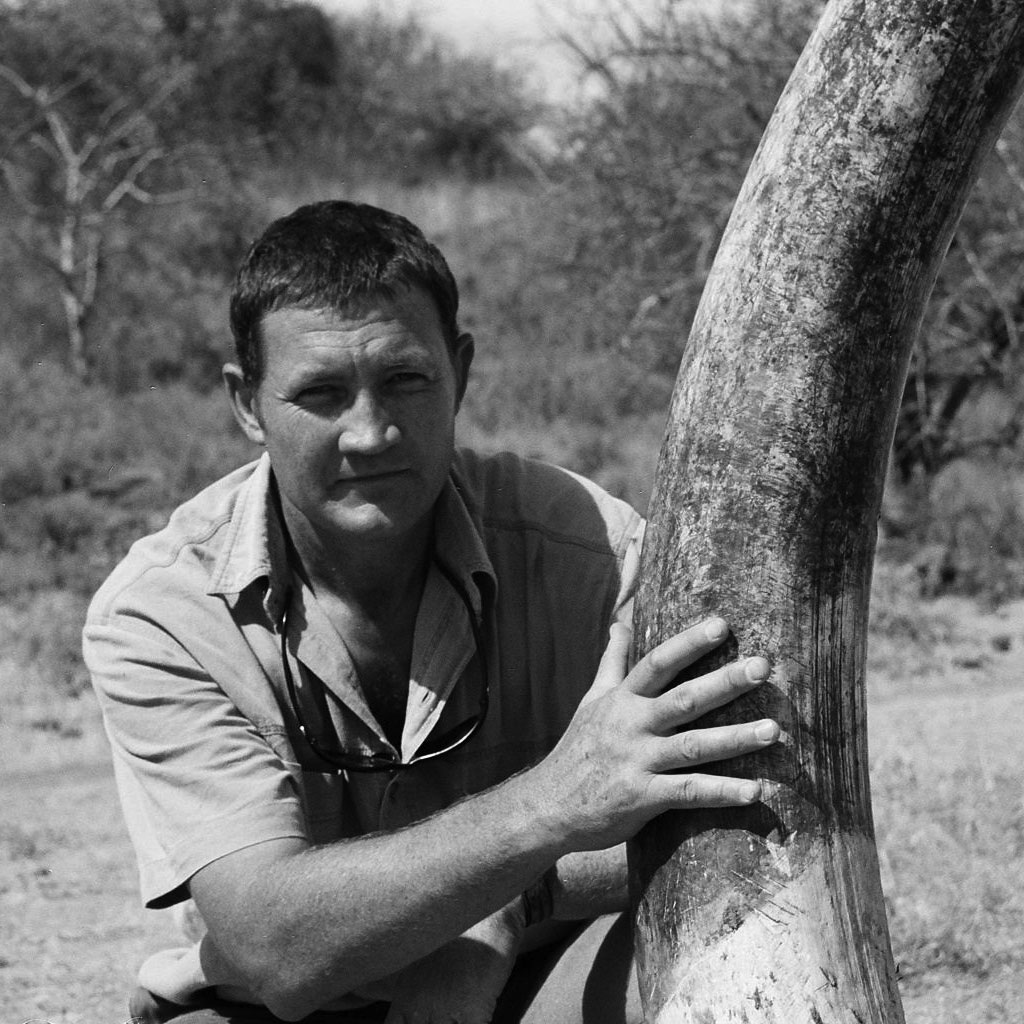

2. K9 Conservation director Conraad de Rosner patrolling with weimaraners.

3. A weimaraner on the scent.

©K9 Conservation

‘Not one rhino has been lost in over a year and a half’

‘The poachers are very weary of patrol dogs and are more willing to give themselves up in a confrontational situation if there is a dog with gnashing teeth in the equation,’ says Director of K9 Conservation, Conraad de Rosner.

There are many arrests in the Kruger National Park region, but unless suspects are found with evidence, they can only be charged with trespassing. Often poachers throw their guns into the bush when they realise they will be caught. But the dogs serve another role by finding those guns and the bullet casings near the poached animals. Fingerprints on weapons and ballistic evidence can lead to stronger convictions. ‘In the areas we operate in, not one rhino has been lost in over a year and a half,’ says co-founder Catherine Corrett. Eight arrests of rhino poachers have been made over that time, and the intelligence from the arrestees has led to more arrests higher up the chain. K9 Conservation is expanding its operations to other key wildlife areas in South Africa. It is developing and consulting on using working dogs in Kenya, Malawi and the Central African Republic.

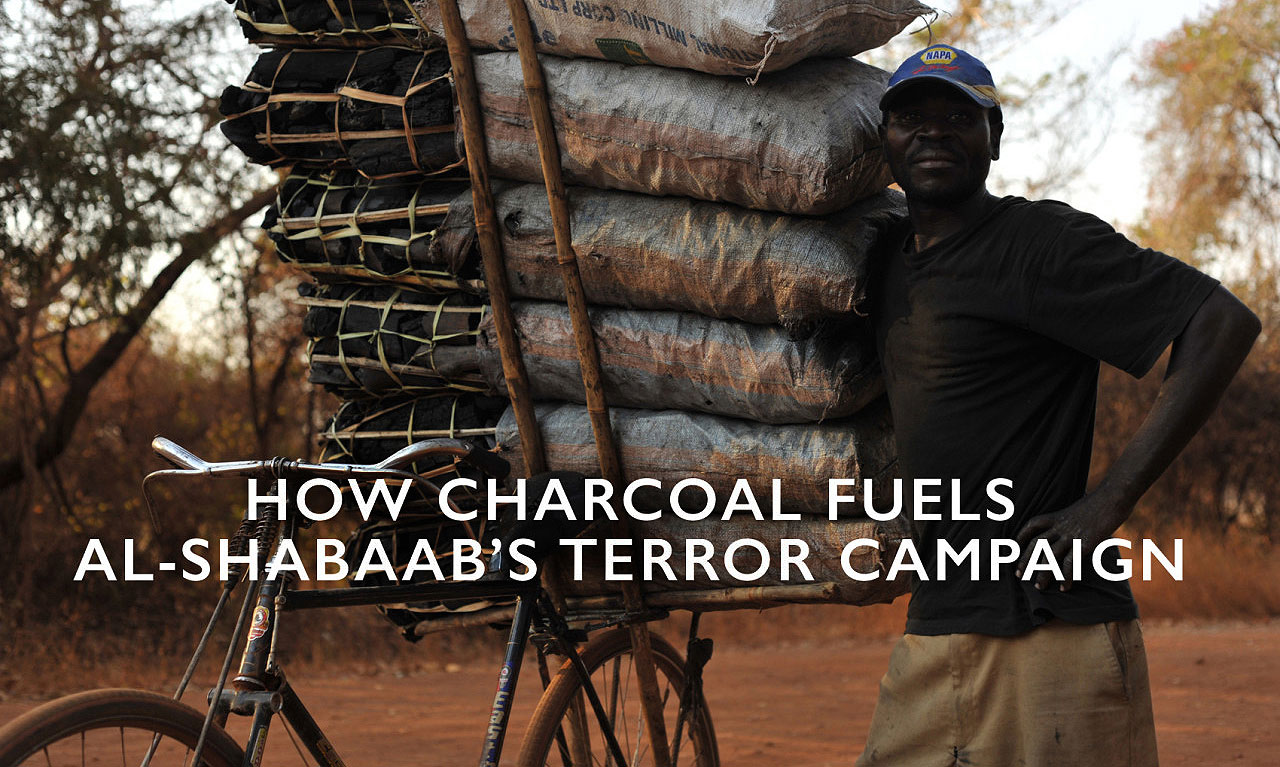

©Congo Hounds

The Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo is a world heritage site. It’s also a hot zone for poaching and war, and 150 rangers have been killed there in the past 17 years. The Congo Hounds Canine Unit, which has been operating since 2011, consists of three bloodhounds and two English springer spaniels. In such a densely forested region with difficult terrain, the bloodhounds are extremely useful because they can follow trails that are days old. They can locate injured rangers or track down poachers intent on killing endangered mountain gorillas and elephants. But that’s where their work stops, as they are too gentle to get involved in actual apprehension. The spaniels are specially trained to sniff out ivory, bush meat and other contraband, so they are used to search vehicles and villages in the region.

2. An English springer spaniel sniffs for ivory, bush meat or other wildlife contraband.

©Congo Hounds

3. Didi, the mix-breed stray turned top tracker. Didi has brought in 6 poachers since being rescued from the ASPCA.

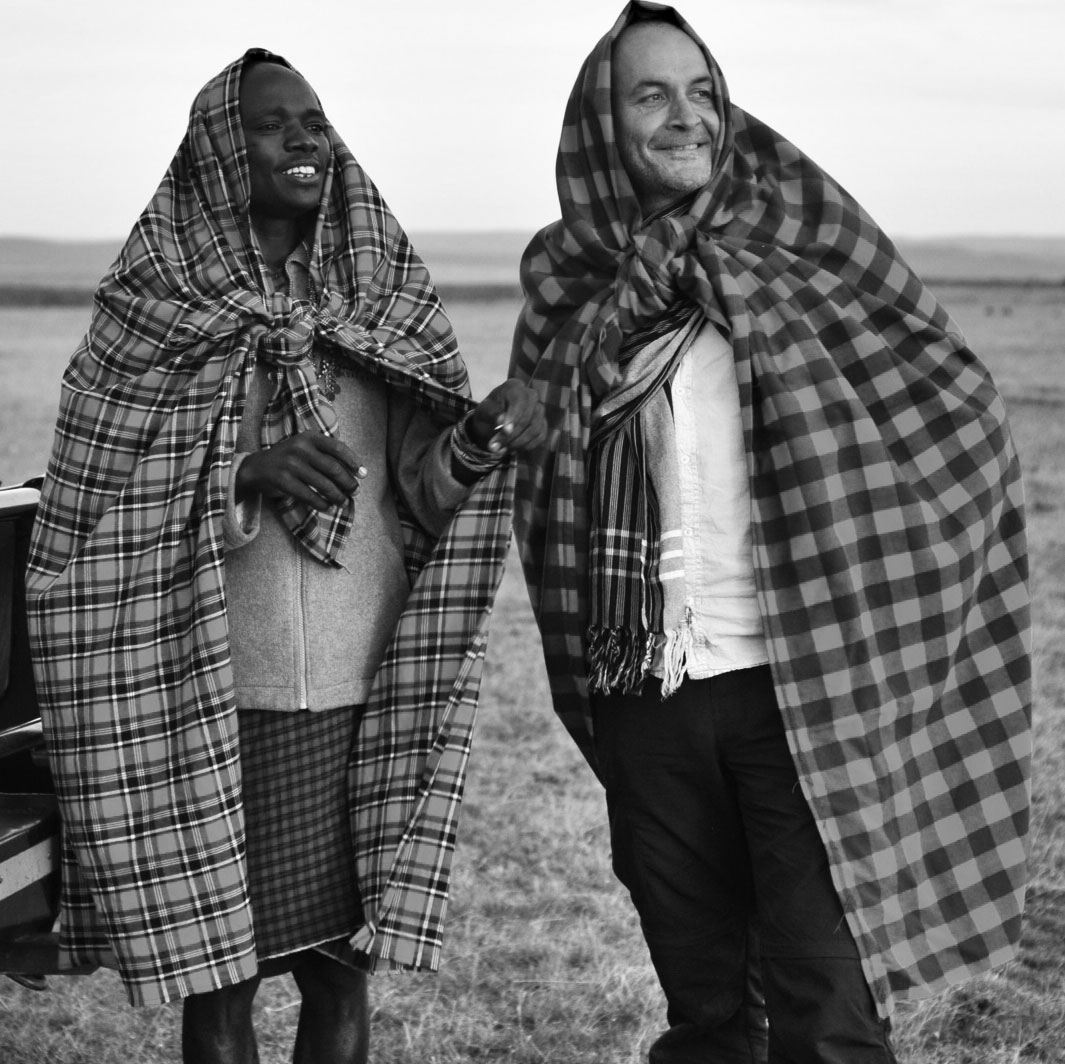

©Big Life

The Big Life Foundation operates on the wildlife-rich plains of East Africa. Launched 4 years ago by British photographer Nick Brandt and Kenyan conservationist Richard Bonham, the foundation now employs 300 rangers in 31 outposts in Tanzania and Kenya. One of their most effective anti-poaching initiatives, the first in Tanzania, is a canine unit comprising German shepherds and German shepherd mix breeds used to track and apprehend poachers. A recent addition to the team is Didi, an abused Nairobi stray Bonham picked up from the ASPCA. With care and training, she has proven herself invaluable, already bringing in 6 poachers and finding two lost community members. Says Leyian, one of her handlers: ‘When we are on the track, we can switch off our minds, Didi is our eyes, and we trust her; she will take us where we want to go.’

|

Further north, within sight of Mount Kenya, is Ol Pejeta Conservancy in the scenic Laikipia region and the last six northern white rhinos on earth. The last of the breeding males died recently, and the fact that he succumbed to natural causes and not a poacher’s gun might well be thanks to Ol Pejeta’s canine unit.

Equipped with camera systems and body armour, this is the dog of the future

The unit comprises two bloodhounds, a black malinois assault dog, and 11 younger Dutch malinois introduced as puppies in 2013. The dogs and their handlers are being trained intensively with British ex-military dog instructor Daryll Pleasants and his White Paw organisation. The focus is on creating multiple roles for the new malinois recruits. Referring to Diego, the son of assault dog Tarzan, Pleasants describes how he is trained to search, track and attack. ‘Not only is Diego part of a new strategy in which one dog can accomplish three roles, but he is also fully approachable. In a conservancy where the general public is free to enjoy the fauna and flora, there is no place for an animal that cannot be controlled.’

But poachers will find these dogs far less approachable. ‘Equipped with state-of-the-art dog surveillance head camera systems and bullet/stab proof body armour, these are the dogs of the future,’ says Pleasants, ‘The dogs that are set to give the conservation world the edge in the war against poaching.’

2. Anatolian Shepherd pups are introduced to livestock herds at a young age in order to grow into devoted protectors.

©CCF/Andrew Harrington

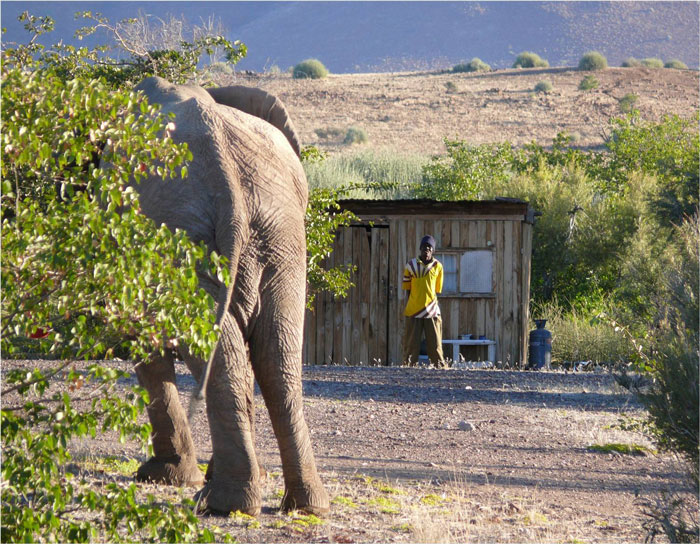

On the periphery of this war, the domestic dog still performs its classic role of friend to domestic animals. Far to the southwest in the arid lands of Namibia, dogs are protecting livestock from predators. Poaching is low in this region, and Namibia’s holistic approach to land use means that livestock and wild animals often cross paths. Because they occasionally prey on livestock, cheetahs and leopards are seen as economic threats and are sometimes killed by farmers. The Cheetah Conservation Fund aims to resolve this conflict using Anatolian shepherd dogs. The dogs, introduced to goat herds at a very young age, have minimal contact with humans, so they grow into devoted protectors of their adopted herd.

Anatolian shepherds are not herding dogs and do not move livestock, which can trigger a predator attack. Rather, they place themselves between the livestock and the threat, barking loudly. If the predator persists they do attack, but often their presence is intimidating enough. Since 1997 over 400 dogs have been placed on farms, with 92% of farmers reporting no loss of livestock or at least a significant reduction.

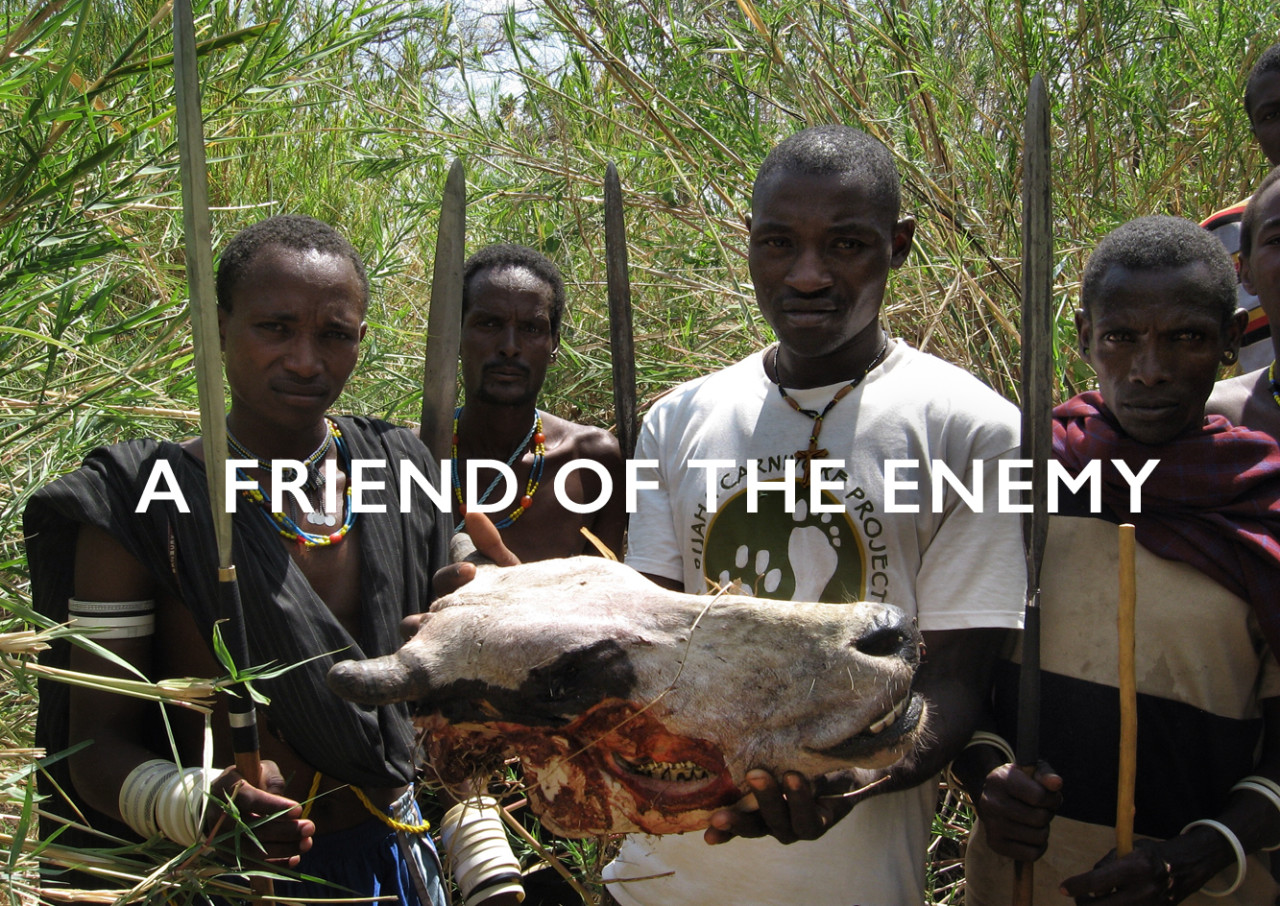

Working with the Ruaha Carnivore Project, the CCF recently introduced young Anatolian shepherd dogs to Barabaig herders near Ruaha National Park in Tanzania. Here, the greatest threat to livestock is not cheetahs and leopards but those haughty lions. The Barabaig people have traditionally protected their herds or even retaliated for kills by spearing and poisoning the cats. But, once the Anatolian shepherd dogs have bonded to the herds and are successful in warding off lion attacks, they may be the lions’ best friends. Perhaps Aesop needs to do a bit of a rewrite.

Contributors

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, and drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, and drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

Wildlife photographer WILL BURRARD-LUCAS first developed a passion for wildlife living in Tanzania as a child. Since then, he has photographed wildlife all over the world and primarily in Africa. Will aims to inspire people to celebrate and conserve the natural wonders of the planet through his imagery. He has partnered with several conservation organisations donating his time and images for their fundraising activities. Working with the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme he draws attention to the challenges this species faces. You can view more of Will’s work on his

Wildlife photographer WILL BURRARD-LUCAS first developed a passion for wildlife living in Tanzania as a child. Since then, he has photographed wildlife all over the world and primarily in Africa. Will aims to inspire people to celebrate and conserve the natural wonders of the planet through his imagery. He has partnered with several conservation organisations donating his time and images for their fundraising activities. Working with the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme he draws attention to the challenges this species faces. You can view more of Will’s work on his

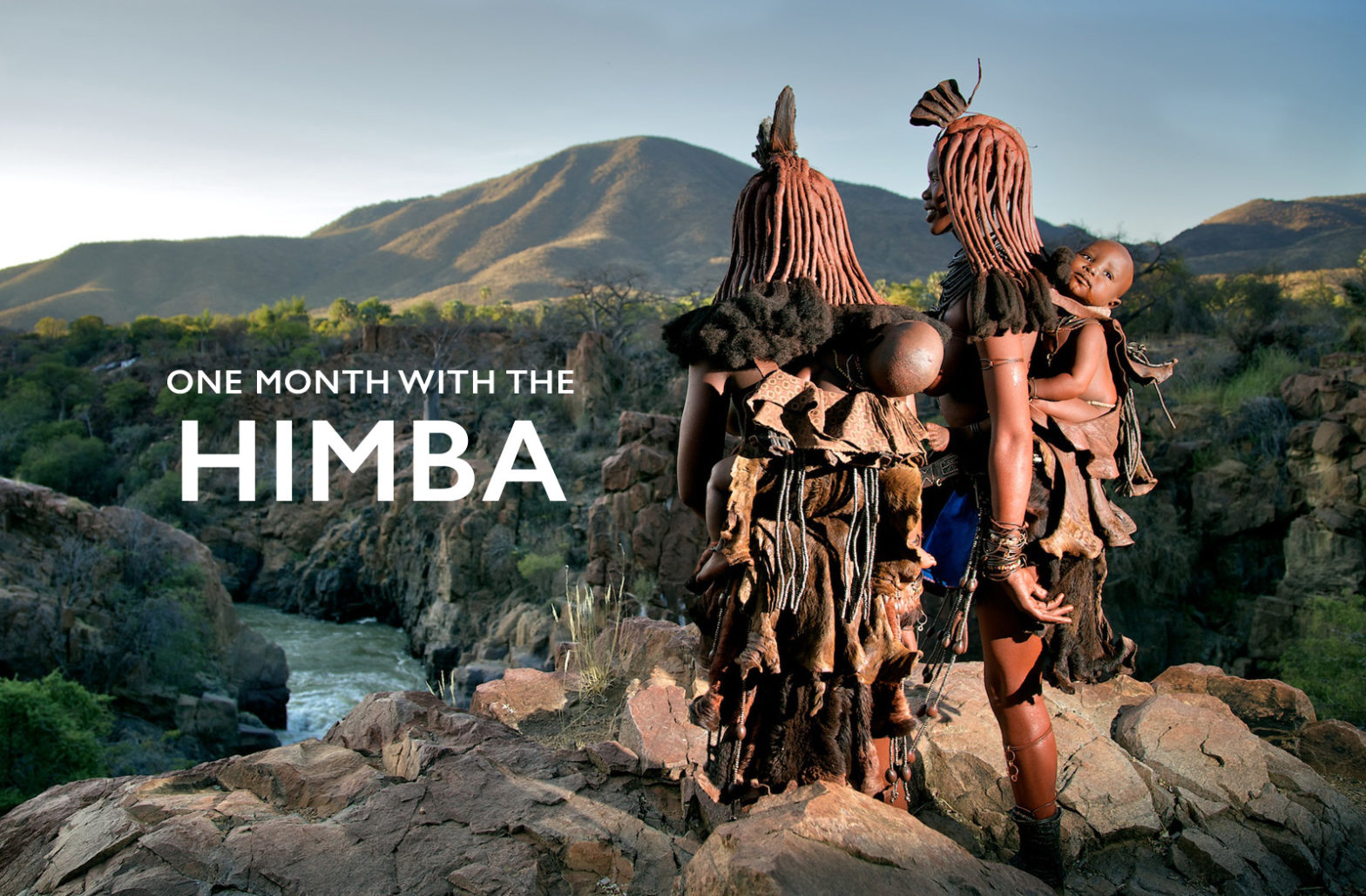

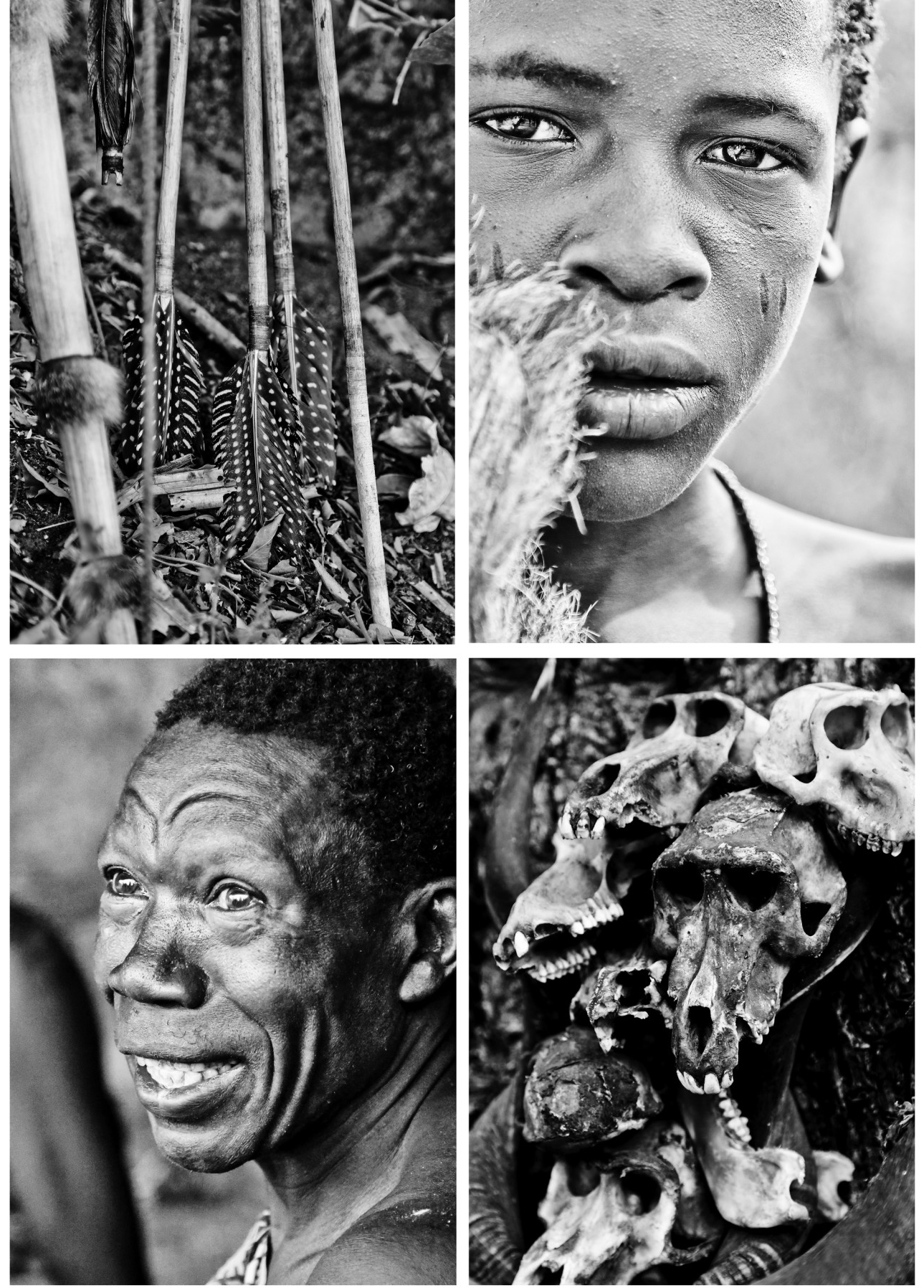

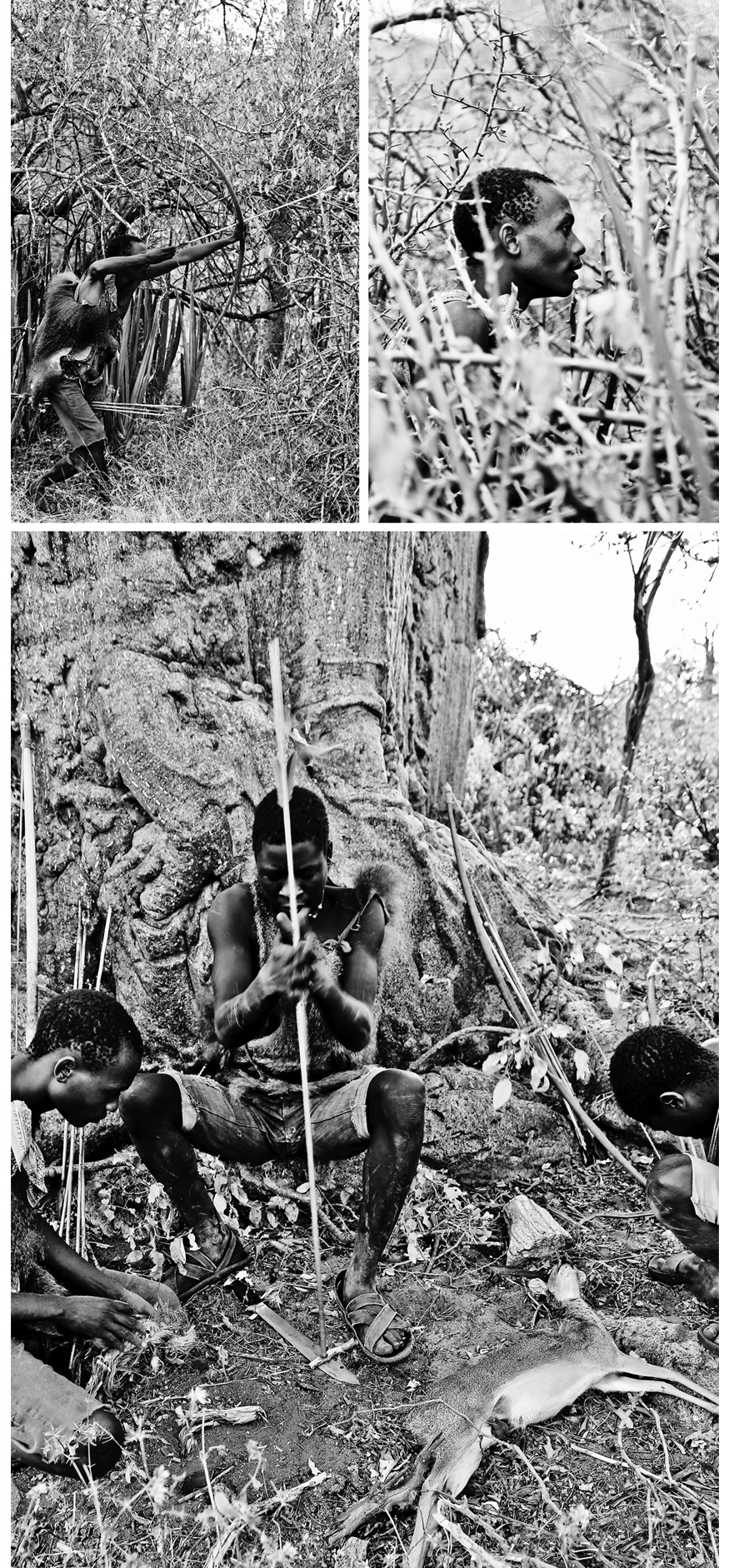

ALEGRA ALLY is a Documentary photographer and a Fellow member of “The Explorers Club NYC”. She currently lives in Sydney, Australia, where she is completing her MA studies in Applied Anthropology. Ally is committed to working on issues relating to empowerment of women and girls, diminishing cultures and the environment. As part of her project ‘

ALEGRA ALLY is a Documentary photographer and a Fellow member of “The Explorers Club NYC”. She currently lives in Sydney, Australia, where she is completing her MA studies in Applied Anthropology. Ally is committed to working on issues relating to empowerment of women and girls, diminishing cultures and the environment. As part of her project ‘

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

JANINE MARÉ is the first to confess that she has been bitten by the travel bug… badly. She loves all things travel, from basic tenting with creepy crawlies to luxury lodges; she will give it all a go. Janine is passionate about wildlife and conservation and comes from a long line of biologists, researchers and botanists. Janine is a former marketing manager at Africa Geographic.

JANINE MARÉ is the first to confess that she has been bitten by the travel bug… badly. She loves all things travel, from basic tenting with creepy crawlies to luxury lodges; she will give it all a go. Janine is passionate about wildlife and conservation and comes from a long line of biologists, researchers and botanists. Janine is a former marketing manager at Africa Geographic.

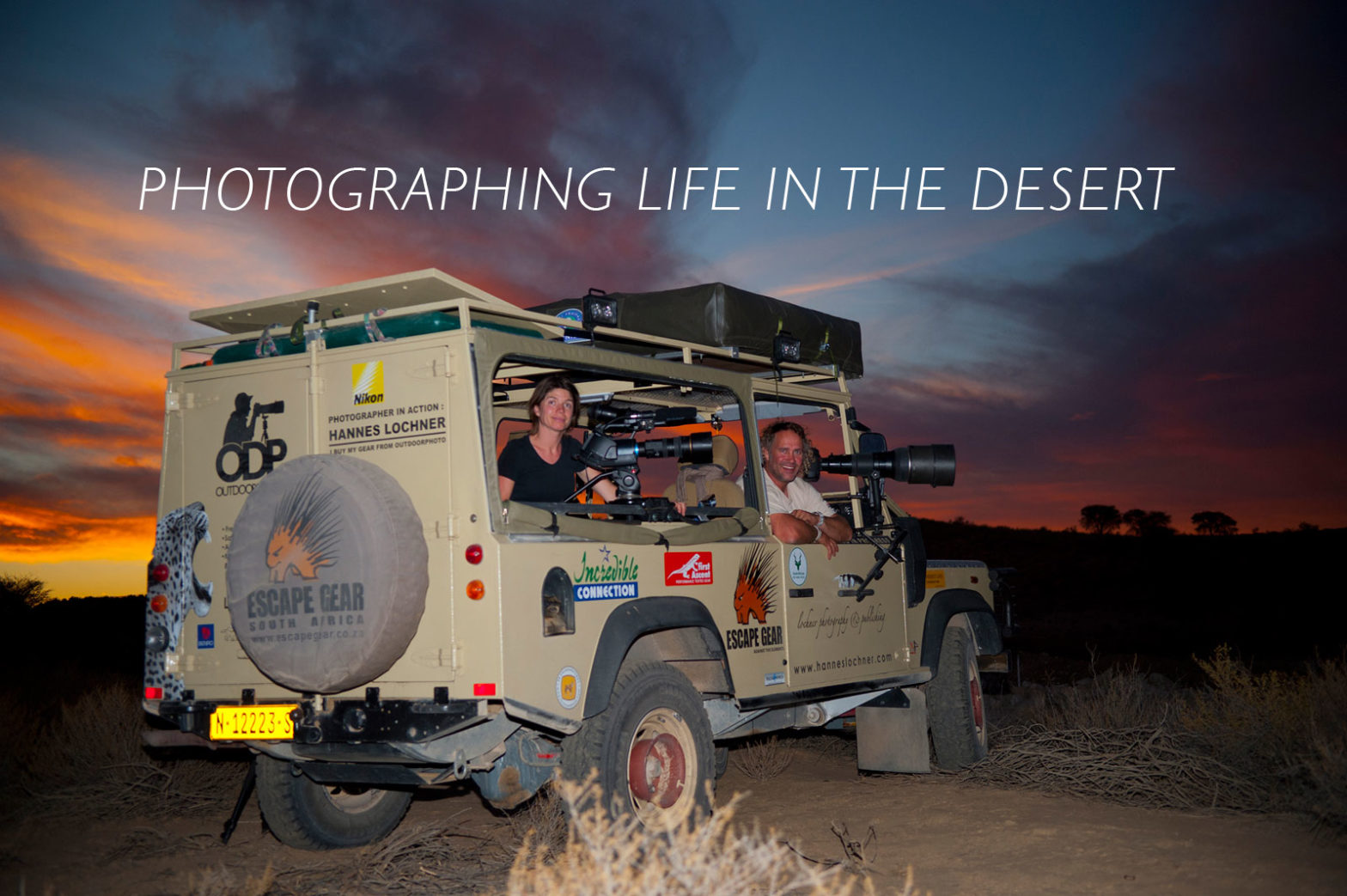

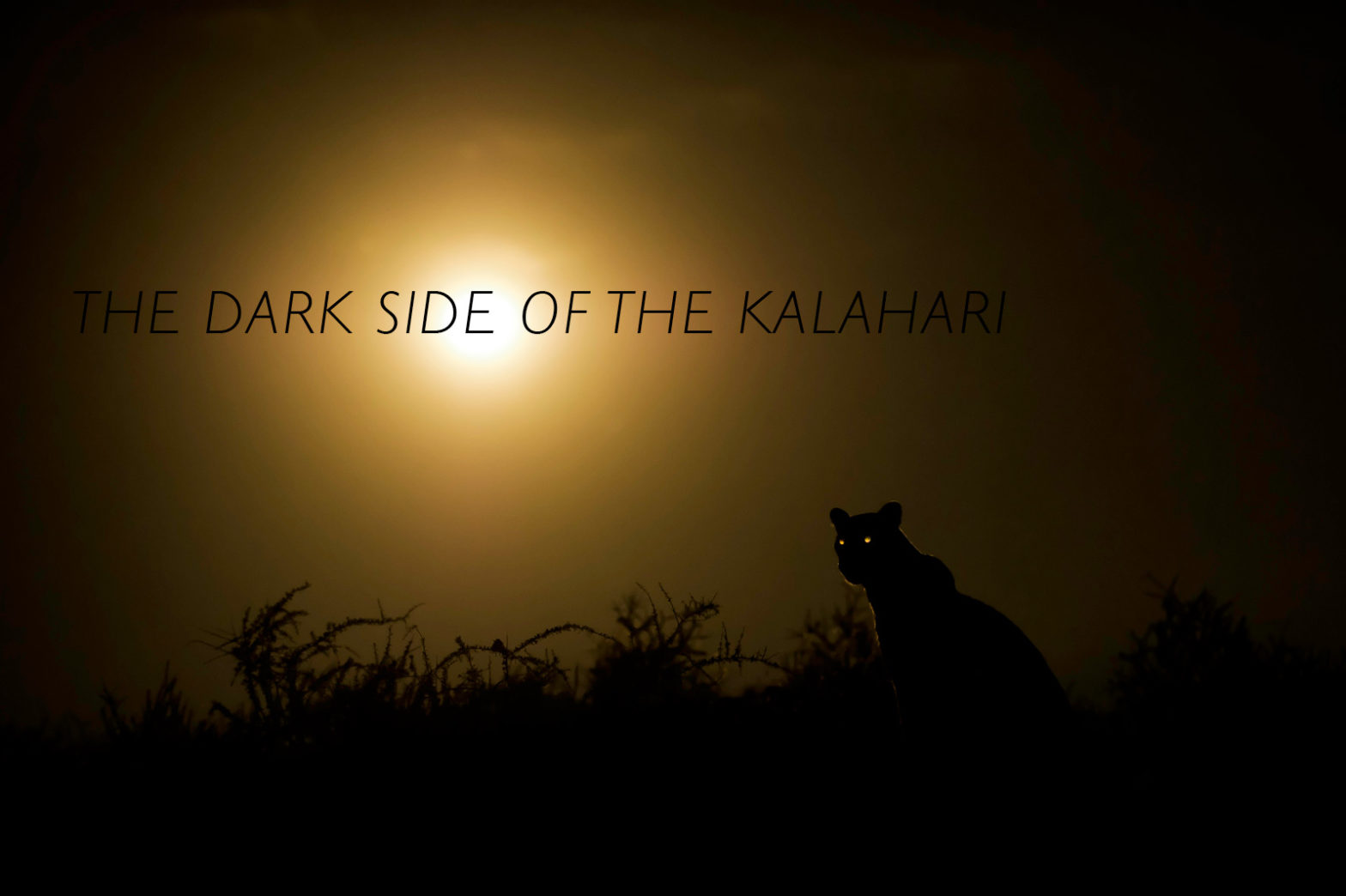

HANNES LOCHNER is a Cape Town-born photographer who has become synonymous with the Kalahari, having spent 5 years photographing the bounteous wildlife of this arid region. Before becoming a full-time wildlife photographer, Hannes was a graphic designer and travelled the world kayaking her rivers intensely. It was on returning to South Africa that he started his own rafting company, acting as a field guide on the Orange and Kunene Rivers. But his love for the fauna of Africa triumphed, and his career as a photographer took off. You can view more of Hannes’ work on his

HANNES LOCHNER is a Cape Town-born photographer who has become synonymous with the Kalahari, having spent 5 years photographing the bounteous wildlife of this arid region. Before becoming a full-time wildlife photographer, Hannes was a graphic designer and travelled the world kayaking her rivers intensely. It was on returning to South Africa that he started his own rafting company, acting as a field guide on the Orange and Kunene Rivers. But his love for the fauna of Africa triumphed, and his career as a photographer took off. You can view more of Hannes’ work on his

The

The  Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are searching for wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife, Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are searching for wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife, Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’

SIMON ESPLEY is a proud African of the digital tribe and honoured to be CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are searching for wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit, next to the Kruger National Park, with his wife Lizz and 2 Jack Russells. When not travelling or working, he is usually on his mountain bike somewhere out there. Simon qualified as a chartered accountant, but found his calling sharing Africa’s incredibleness with you. His motto is “Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change”.

SIMON ESPLEY is a proud African of the digital tribe and honoured to be CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are searching for wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit, next to the Kruger National Park, with his wife Lizz and 2 Jack Russells. When not travelling or working, he is usually on his mountain bike somewhere out there. Simon qualified as a chartered accountant, but found his calling sharing Africa’s incredibleness with you. His motto is “Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change”. A special thanks to MARIA DIEKMANN, founder and director of

A special thanks to MARIA DIEKMANN, founder and director of  CHRISTIAN BOIX left his native Spain, its great food, siestas and fiestas, to become an ornithologist at the University of Cape Town and a specialist bird guide. Time passed, his daughter became convinced he was some kind of pilot, and his wife acquired a budgie for company – that’s when the penny dropped. Thrilled to join the Africa Geographic team; Christian is their resident safari expert and guide.

CHRISTIAN BOIX left his native Spain, its great food, siestas and fiestas, to become an ornithologist at the University of Cape Town and a specialist bird guide. Time passed, his daughter became convinced he was some kind of pilot, and his wife acquired a budgie for company – that’s when the penny dropped. Thrilled to join the Africa Geographic team; Christian is their resident safari expert and guide. JUDY & SCOTT HURD are photographers living and working in Namibia, a country they see as the most photogenic on the planet. They have accumulated a huge wildlife library, some of which you can view on their

JUDY & SCOTT HURD are photographers living and working in Namibia, a country they see as the most photogenic on the planet. They have accumulated a huge wildlife library, some of which you can view on their

A special thanks goes to

A special thanks goes to

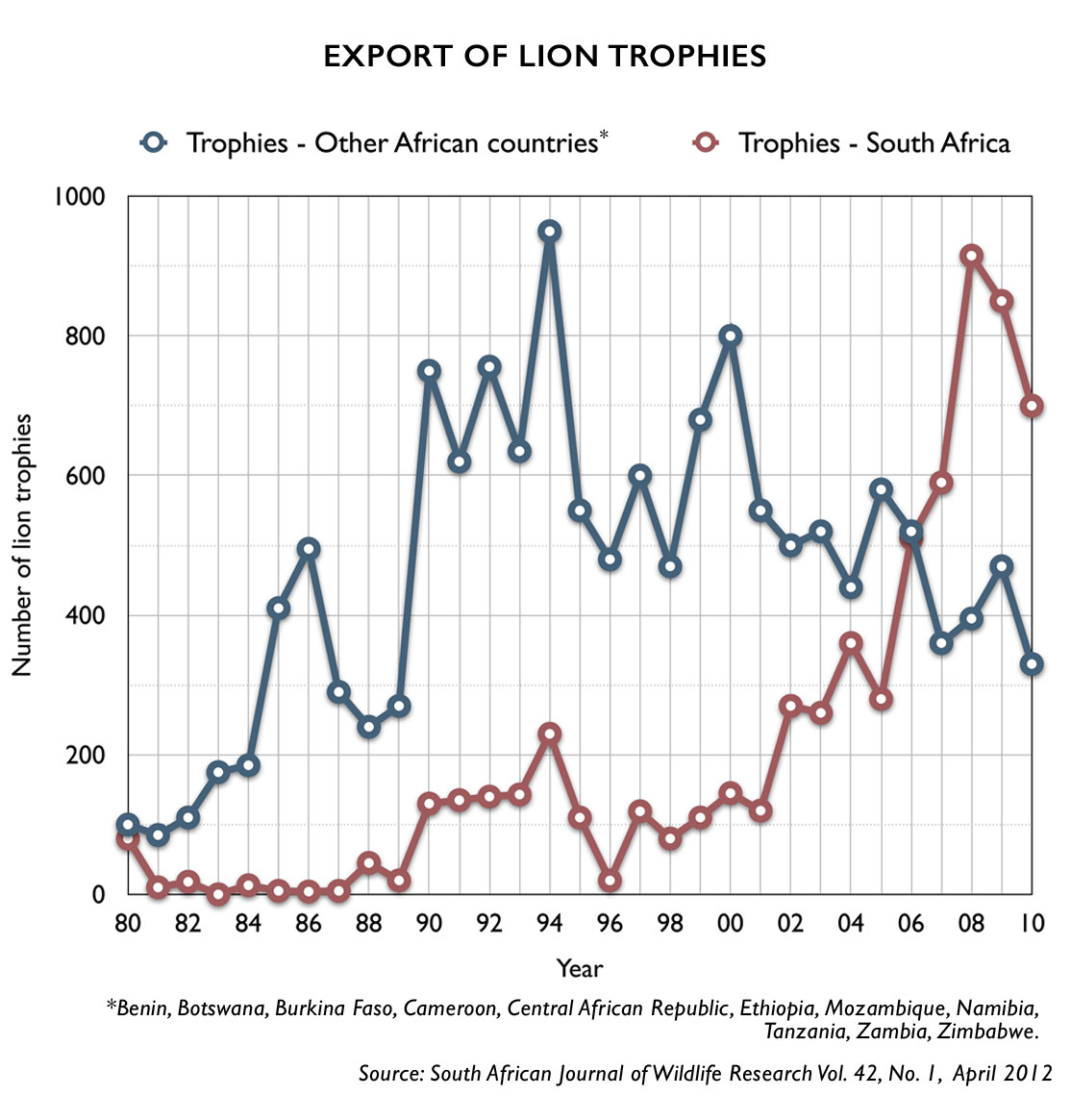

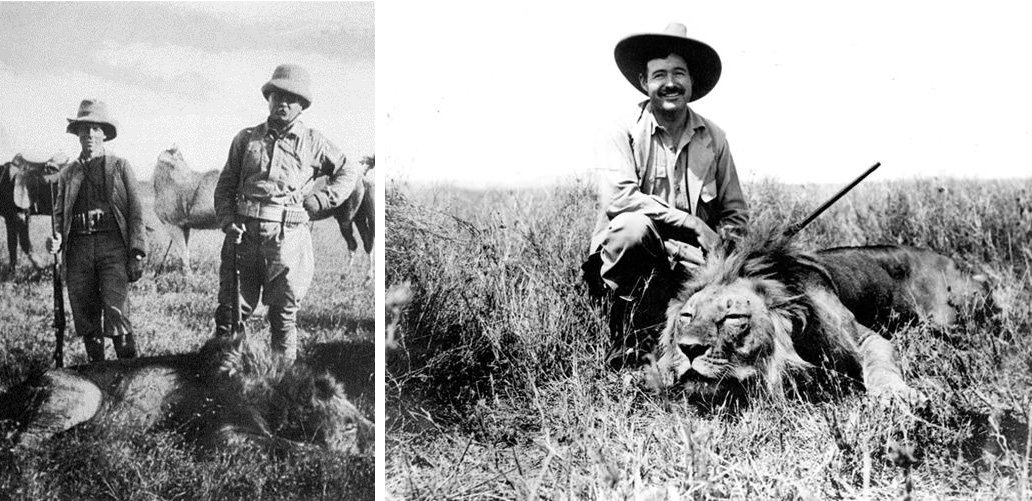

The USA is by far the largest market for trophies. The key drivers seem to be a large, wealthy hunting population and a colourful history of African big game hunting featuring iconic characters such as President Theodore Roosevelt, whose year-long African safari is the stuff of legends. In 1909, he and his son bagged over 500 big game, including 17 lions, 11 elephants and 20 rhinos.

The USA is by far the largest market for trophies. The key drivers seem to be a large, wealthy hunting population and a colourful history of African big game hunting featuring iconic characters such as President Theodore Roosevelt, whose year-long African safari is the stuff of legends. In 1909, he and his son bagged over 500 big game, including 17 lions, 11 elephants and 20 rhinos.

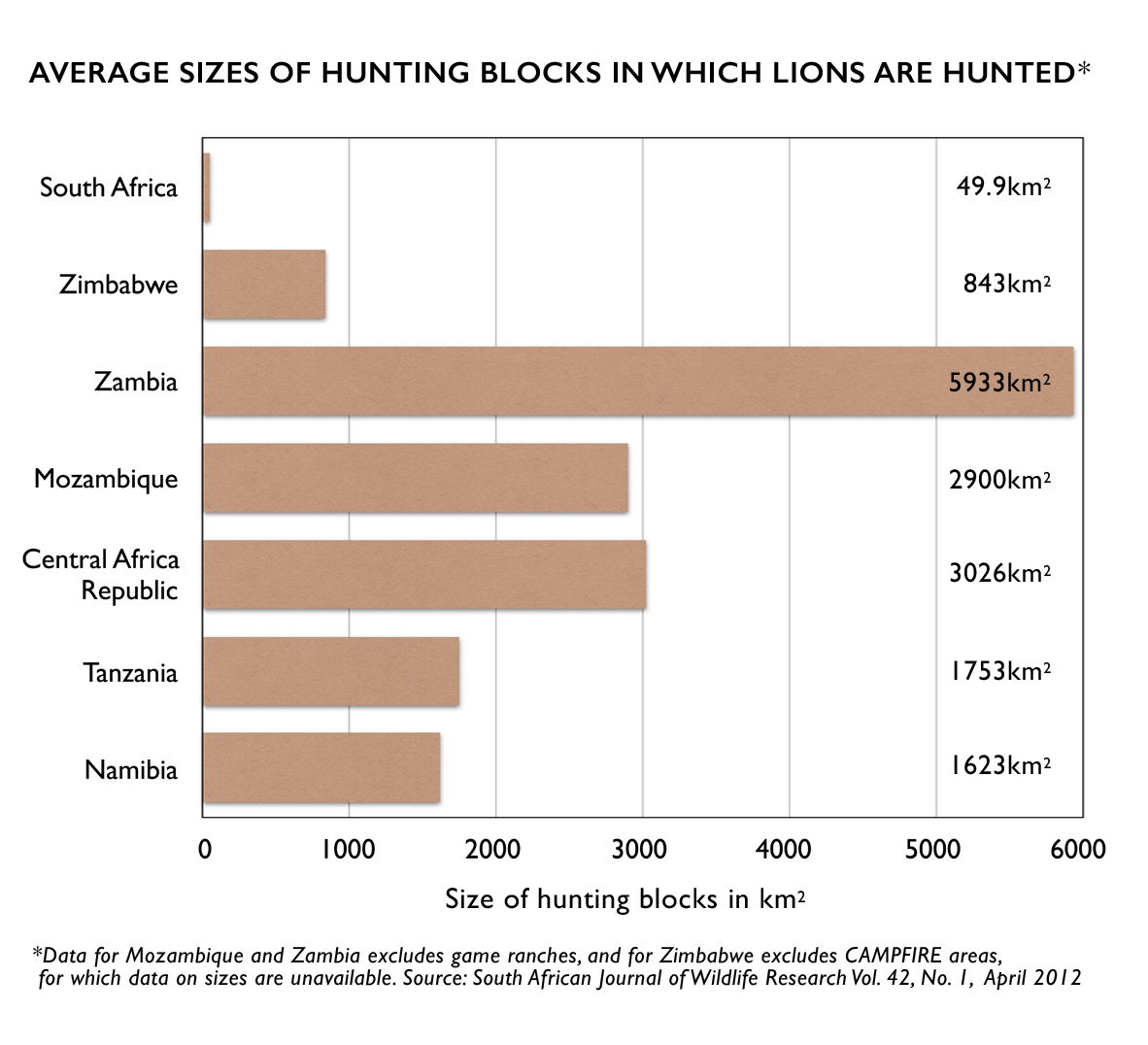

The South African Predator Association stipulates a minimum of 10km² hunting area for captive-bred lions. The legally required release period for captive-bred lions in the Free State Province and North West Province is 30 and 4 days, respectively (FS and NW are where most captive-bred lions are hunted)

The South African Predator Association stipulates a minimum of 10km² hunting area for captive-bred lions. The legally required release period for captive-bred lions in the Free State Province and North West Province is 30 and 4 days, respectively (FS and NW are where most captive-bred lions are hunted)

Scott Ramsay is still out there somewhere. But he’s not hiding. Through his work, Scott hopes to inspire others to travel to the continent’s national parks, and nature reserves, which Scott believes are Africa’s greatest assets and deserve to be protected at any cost, not only for their sake but for our own survival. His one-year journey to explore South Africa’s wild places turned into three. Perhaps as the wild places beyond South Africa’s borders lure him, the journey will continue for many years.

Scott Ramsay is still out there somewhere. But he’s not hiding. Through his work, Scott hopes to inspire others to travel to the continent’s national parks, and nature reserves, which Scott believes are Africa’s greatest assets and deserve to be protected at any cost, not only for their sake but for our own survival. His one-year journey to explore South Africa’s wild places turned into three. Perhaps as the wild places beyond South Africa’s borders lure him, the journey will continue for many years.

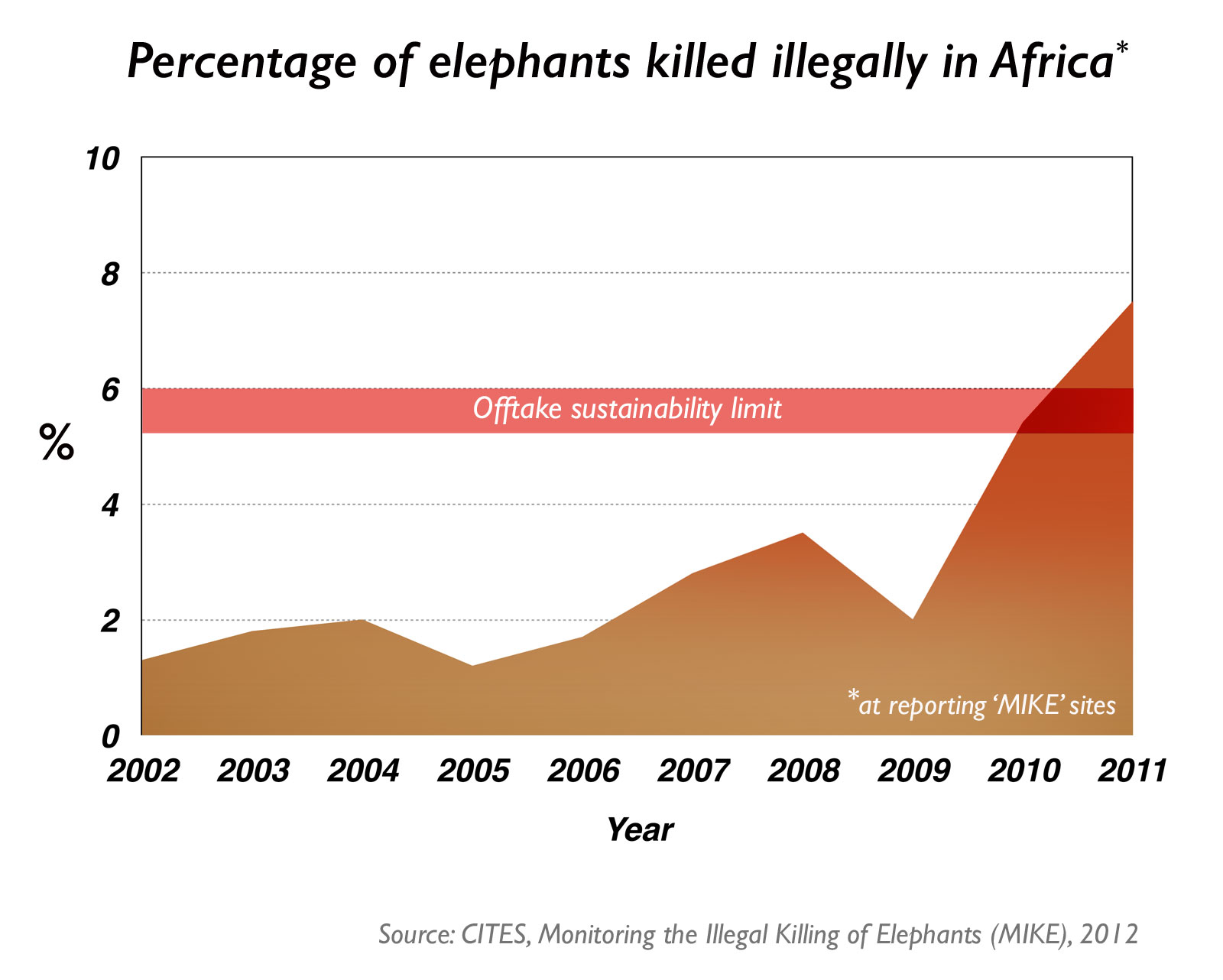

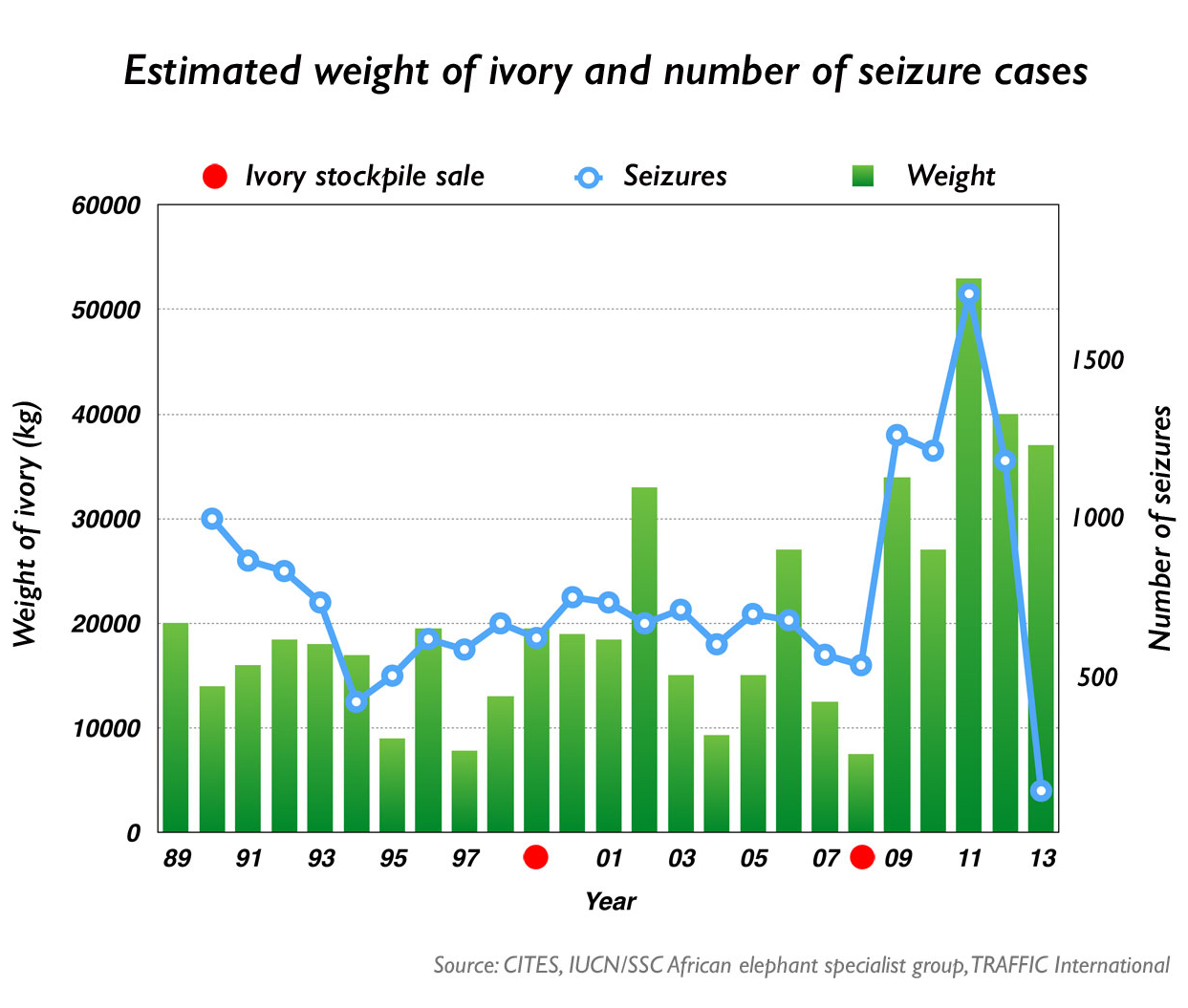

‘The two objectives were to put money from those sales back into the hands of environmental law enforcement to increase conservation efforts further and to provide support and revenue for local communities,’ Bergin says. The experiment did not work, he continues to explain, because no one anticipated China’s tremendous economic rise, the huge increase in disposable income in that country, and the significant level of money laundering made possible by that new prosperity.

‘The two objectives were to put money from those sales back into the hands of environmental law enforcement to increase conservation efforts further and to provide support and revenue for local communities,’ Bergin says. The experiment did not work, he continues to explain, because no one anticipated China’s tremendous economic rise, the huge increase in disposable income in that country, and the significant level of money laundering made possible by that new prosperity.

MICHAEL SCHWARTZ is an American freelance writer, consultant and member of the

MICHAEL SCHWARTZ is an American freelance writer, consultant and member of the

DR. ROWAN MARTIN has been of vital assistance in writing this issue. Rowan heads up the

DR. ROWAN MARTIN has been of vital assistance in writing this issue. Rowan heads up the  CHRISTIAN MEERMANN is the photographer of our

CHRISTIAN MEERMANN is the photographer of our

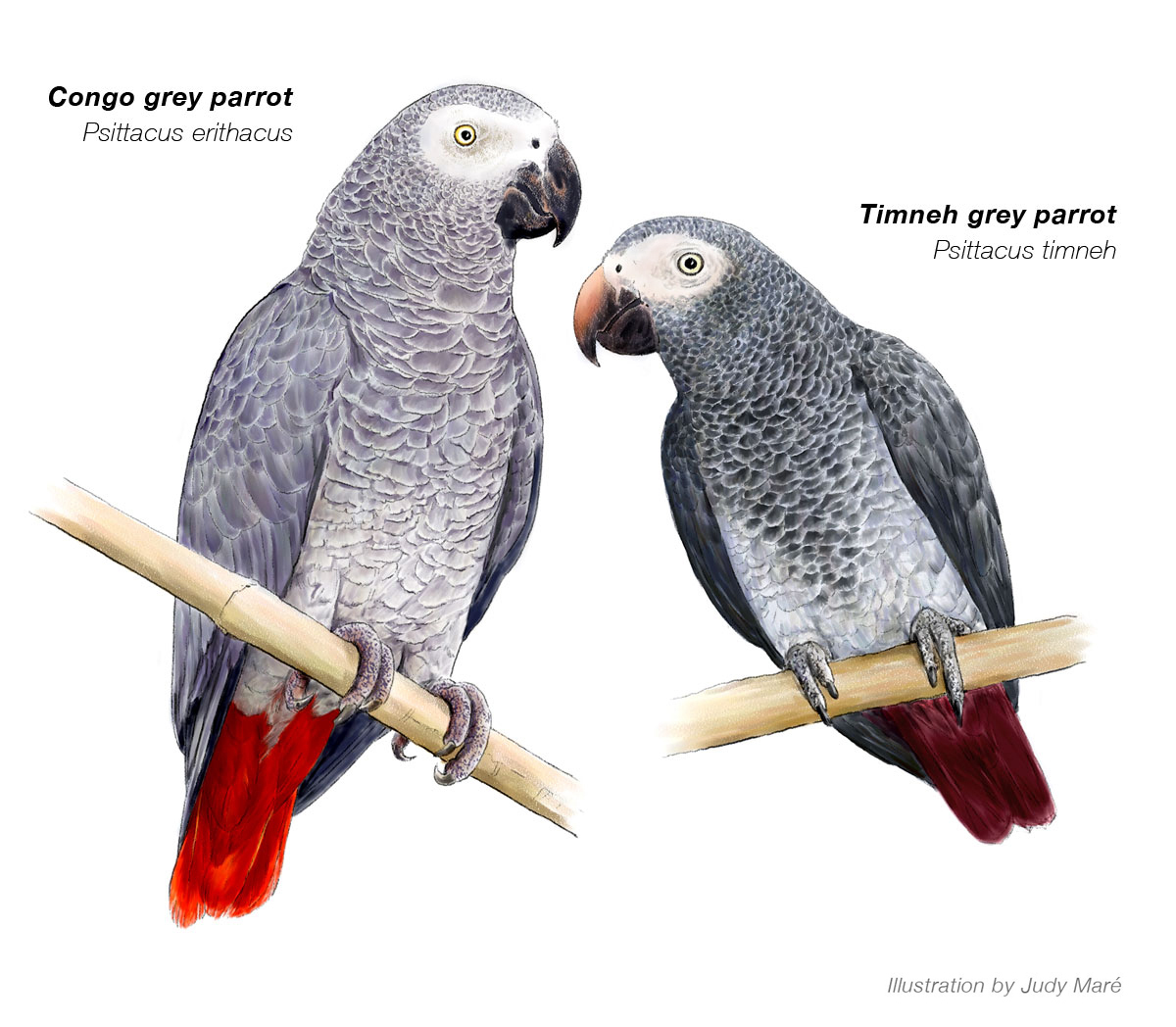

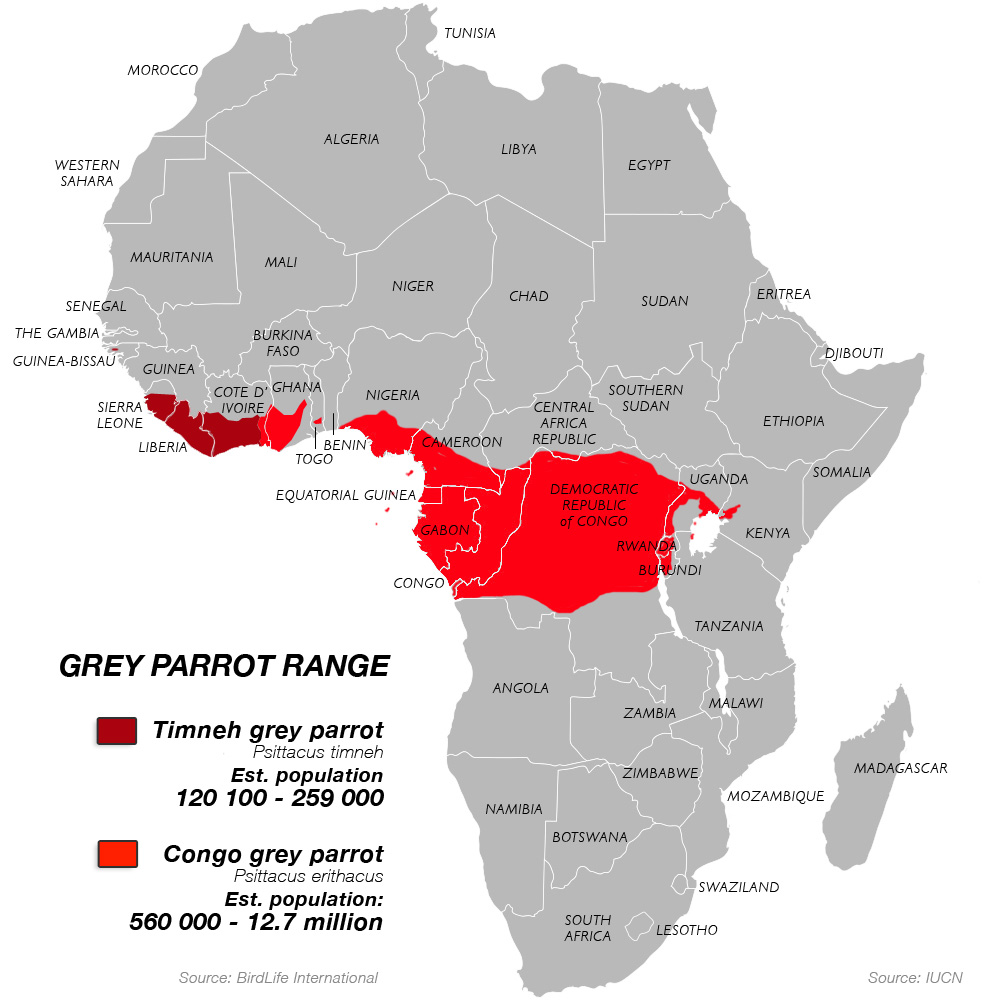

Congo grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus)

Congo grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus) Population

Population

ETHAN KINSEYwas born and raised close to Arusha, where he and his wife now make their home. Being outside, immersed in nature, has always been a part of his life, from catching tadpoles, birding and outdoor pursuits as a child, to winter sports during college vacations. More recently, it has taken the form of sharing wildlife and wilderness experiences with guests, specialized guiding, guide-training, and personal learning ventures. Primarily occupied with designing and guiding private safaris throughout East Africa, he is also active in the training and developing of guiding standards through the

ETHAN KINSEYwas born and raised close to Arusha, where he and his wife now make their home. Being outside, immersed in nature, has always been a part of his life, from catching tadpoles, birding and outdoor pursuits as a child, to winter sports during college vacations. More recently, it has taken the form of sharing wildlife and wilderness experiences with guests, specialized guiding, guide-training, and personal learning ventures. Primarily occupied with designing and guiding private safaris throughout East Africa, he is also active in the training and developing of guiding standards through the

What has always fascinated me is how nature comes up with the most marvellous combinations of colour. It is these combinations of colour and design that spark many of my pictures. I have always loved painting birds; their patterns and colours are superb.

What has always fascinated me is how nature comes up with the most marvellous combinations of colour. It is these combinations of colour and design that spark many of my pictures. I have always loved painting birds; their patterns and colours are superb. I paint because it is what I love to do. I paint what inspires me or challenges me. It is very hard to catch that same spontaneous ‘inspiration’ from someone else’s idea. In the few commissions I have done, I am constantly wondering: ‘is this what they had in mind?’ I concluded that it would be unwise to accept commissions as, although one might be tempted to follow this route as it brings in money, in the end, it will be detrimental to one’s standard of work and one’s own inspiration. I can afford not to be controlled by fear of not having enough money because I know tomorrow will take care of itself.

I paint because it is what I love to do. I paint what inspires me or challenges me. It is very hard to catch that same spontaneous ‘inspiration’ from someone else’s idea. In the few commissions I have done, I am constantly wondering: ‘is this what they had in mind?’ I concluded that it would be unwise to accept commissions as, although one might be tempted to follow this route as it brings in money, in the end, it will be detrimental to one’s standard of work and one’s own inspiration. I can afford not to be controlled by fear of not having enough money because I know tomorrow will take care of itself.

I am compiling countless little stories of my encounters and observations of the wonderful wildlife using photographs and sketches. And I have many oil paintings that are simmering away in my head, waiting for the right moment to appear on the canvas. These will be done randomly in between all the other projects. I will also be exhibiting and giving a talk in Vancouver at the Artist For Conservation exhibition at the end of September 2014.

I am compiling countless little stories of my encounters and observations of the wonderful wildlife using photographs and sketches. And I have many oil paintings that are simmering away in my head, waiting for the right moment to appear on the canvas. These will be done randomly in between all the other projects. I will also be exhibiting and giving a talk in Vancouver at the Artist For Conservation exhibition at the end of September 2014.

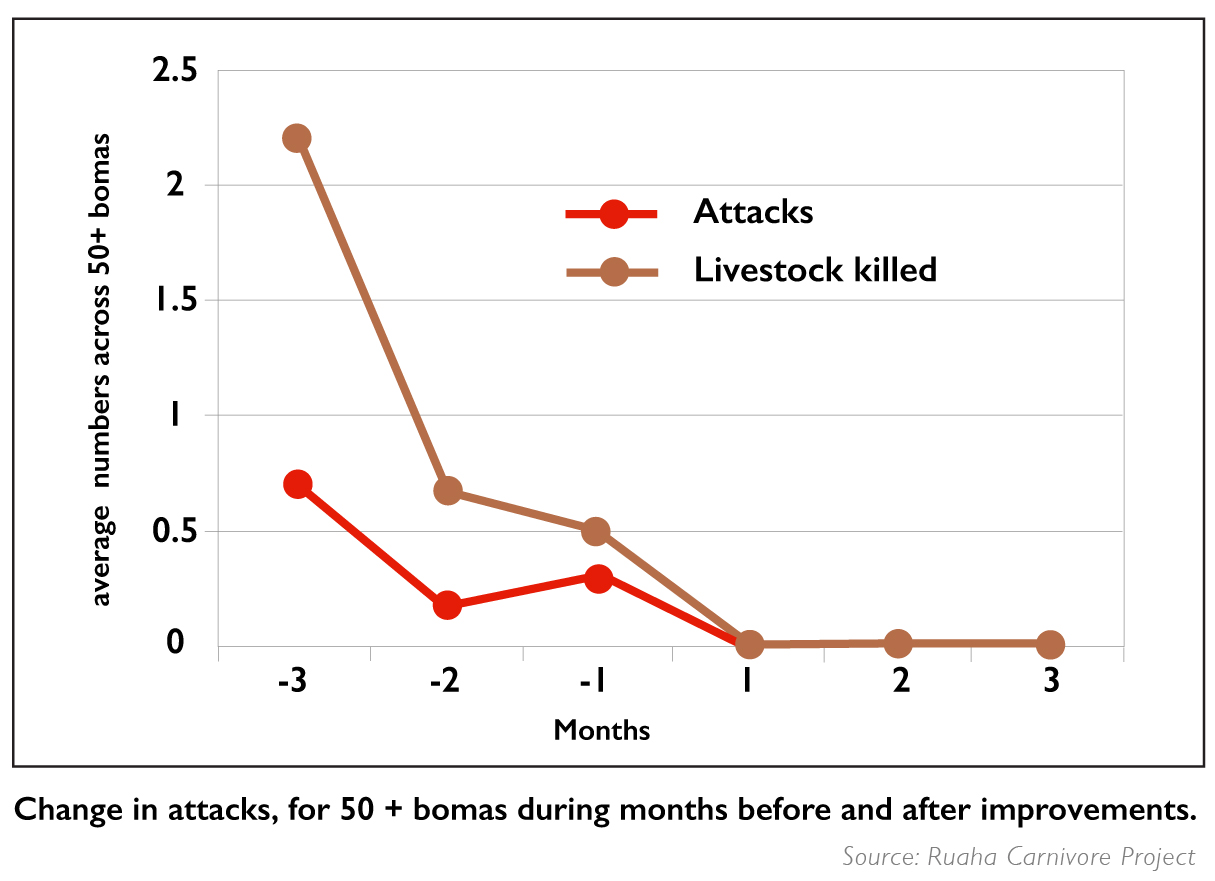

Our research showed that 65% of attacks occurred in livestock enclosures (bomas), the majority of which were poorly constructed. We introduced a cost-sharing initiative to construct predator-proof bomas made of diamond-mesh fencing. To date, we have constructed over 70, and they have proved 100% effective at preventing attacks. However, some attacks occur in the bush, so we have begun trials using specially trained Anatolian shepherd dogs to guard livestock. Although the project is in its infancy, the approach seems promising. In addition, we work intensively with village households to teach people how to identify carnivore attacks and how simple, low-tech measures can prevent such attacks from recurring. Together these measures have significantly reduced depredation, reducing economic pressures on people and the need for preventative or retaliatory killing.

Our research showed that 65% of attacks occurred in livestock enclosures (bomas), the majority of which were poorly constructed. We introduced a cost-sharing initiative to construct predator-proof bomas made of diamond-mesh fencing. To date, we have constructed over 70, and they have proved 100% effective at preventing attacks. However, some attacks occur in the bush, so we have begun trials using specially trained Anatolian shepherd dogs to guard livestock. Although the project is in its infancy, the approach seems promising. In addition, we work intensively with village households to teach people how to identify carnivore attacks and how simple, low-tech measures can prevent such attacks from recurring. Together these measures have significantly reduced depredation, reducing economic pressures on people and the need for preventative or retaliatory killing.

GREG LEDERLE is a multiple award-winning guide and the owner and co-founder of his own safari company – Lederle Safaris. Described by Forbes Life as “…a warm and effervescent personality”, Greg’s connection to and appreciation of Africa and travel is evident in his pursuit of off-the-beaten-track safari experiences.

GREG LEDERLE is a multiple award-winning guide and the owner and co-founder of his own safari company – Lederle Safaris. Described by Forbes Life as “…a warm and effervescent personality”, Greg’s connection to and appreciation of Africa and travel is evident in his pursuit of off-the-beaten-track safari experiences.

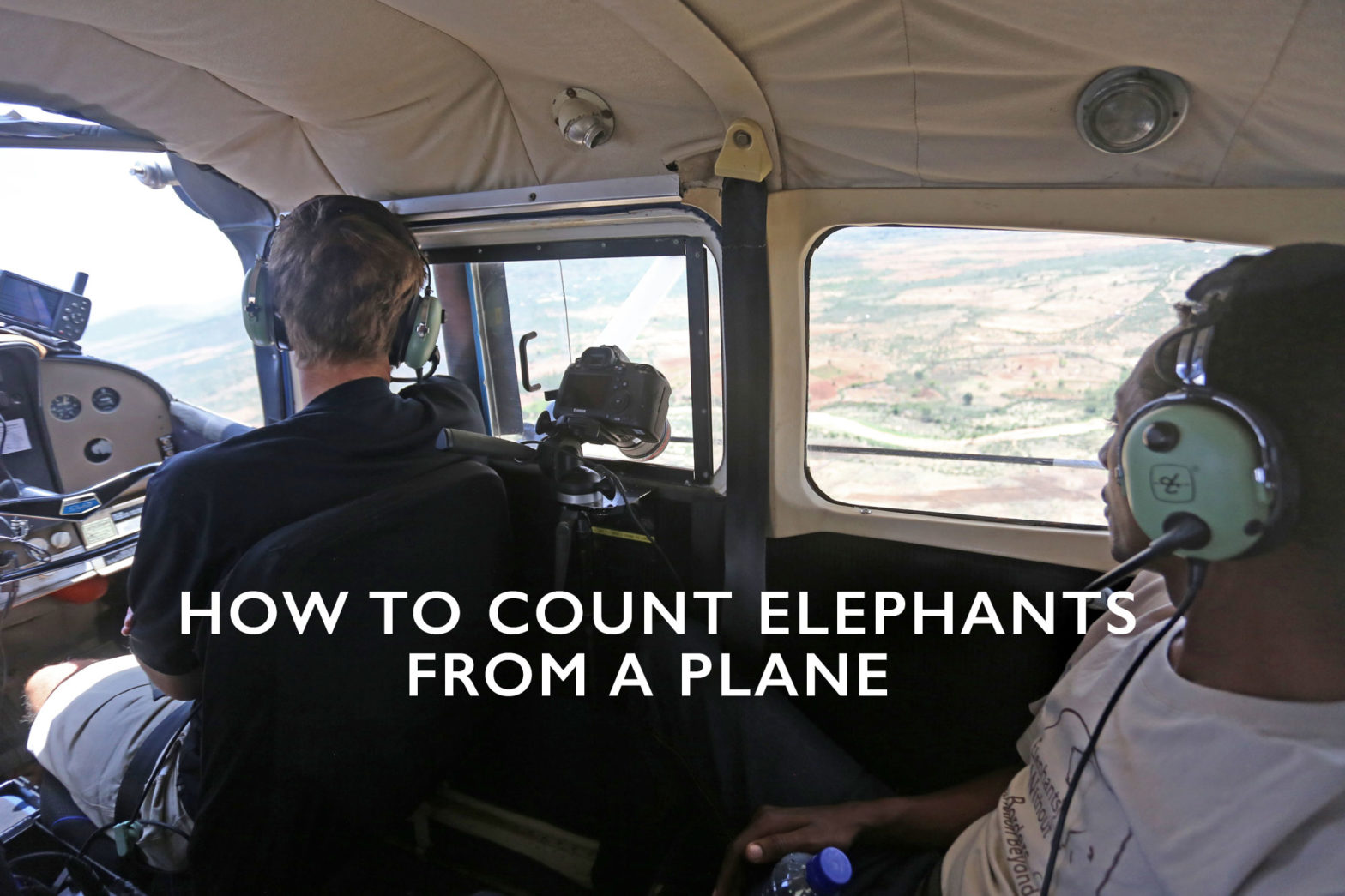

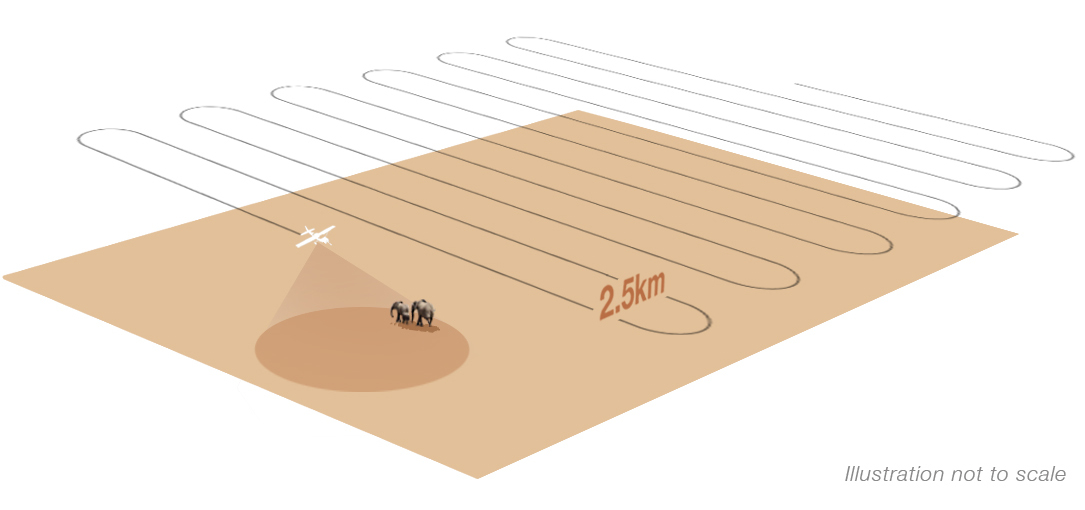

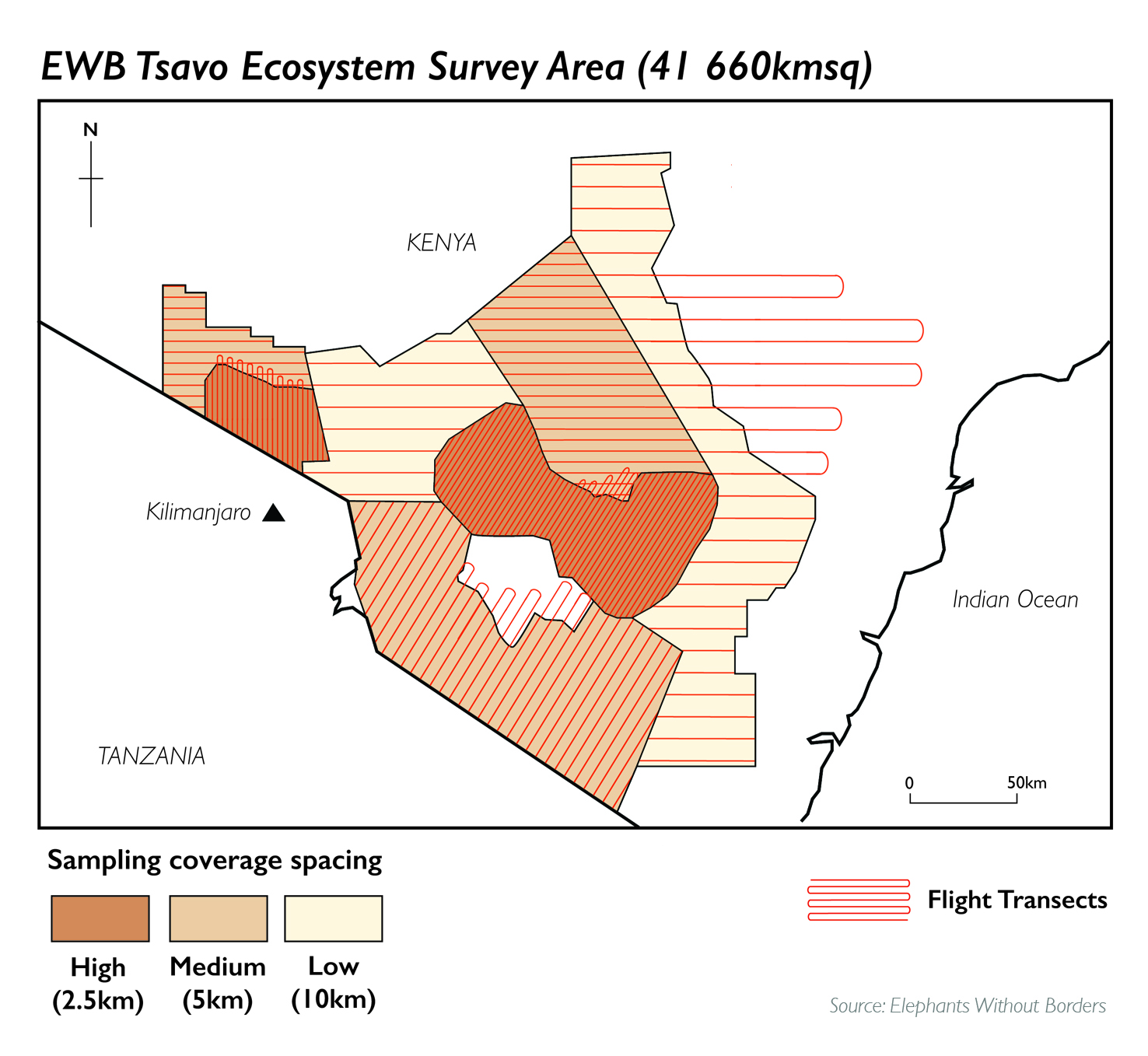

A typical total aerial count covers 100% of the target area, flying strips spaced 1 kilometre apart. A sample count differs in that it flies strips spaced further apart and covers areas chosen by factors such as the concentration of elephants and natural habitat. The strip spacing varies accordingly.

A typical total aerial count covers 100% of the target area, flying strips spaced 1 kilometre apart. A sample count differs in that it flies strips spaced further apart and covers areas chosen by factors such as the concentration of elephants and natural habitat. The strip spacing varies accordingly.

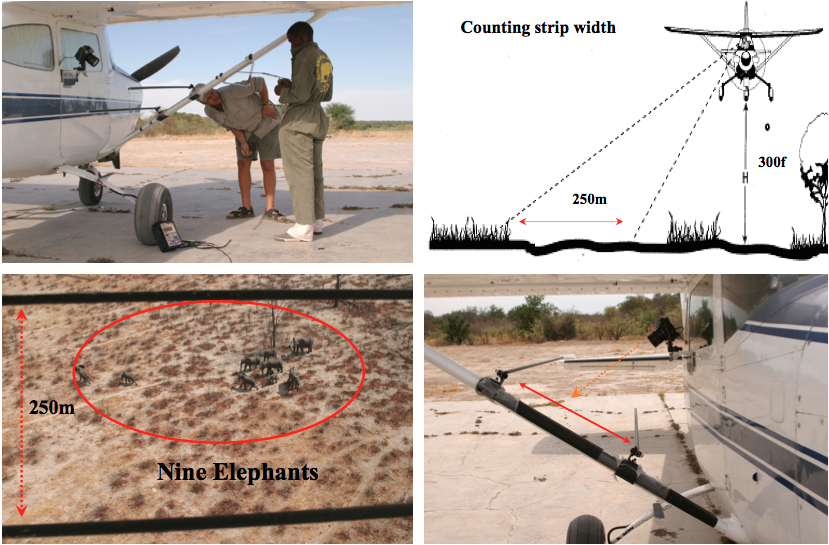

The plane flies at a certain altitude which keeps the area within a designated width of ground coverage, seen between the wands. The observer counts, and photos are taken of the wildlife seen between the wands. This is important for post-analysis for the population numbers to be extrapolated, considering ground coverage that could not be flown. The system is applied on both sides of the plane with at least 1 observer per side.

The plane flies at a certain altitude which keeps the area within a designated width of ground coverage, seen between the wands. The observer counts, and photos are taken of the wildlife seen between the wands. This is important for post-analysis for the population numbers to be extrapolated, considering ground coverage that could not be flown. The system is applied on both sides of the plane with at least 1 observer per side.

KELLY LANDEN threw down an anchor in 2002, abandoning a career on the oceans to dedicate herself to African conservation. Having a passion for wildlife and an affinity for photography, as

KELLY LANDEN threw down an anchor in 2002, abandoning a career on the oceans to dedicate herself to African conservation. Having a passion for wildlife and an affinity for photography, as  RICHARD MOLLER is one of Kenya’s most respected hands-on conservation project managers. As co-founder of the

RICHARD MOLLER is one of Kenya’s most respected hands-on conservation project managers. As co-founder of the  MARK MULLER was born & raised on a Coffee farm on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. He was schooled in Tanzania and Kenya and, immediately after school, came to Maun in Botswana, where he has spent the last 42 years. He has always had a passion for wildlife, with a particular love of elephants and birds. His love of photography was first sparked on a trip to Antarctica in 2006.

MARK MULLER was born & raised on a Coffee farm on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. He was schooled in Tanzania and Kenya and, immediately after school, came to Maun in Botswana, where he has spent the last 42 years. He has always had a passion for wildlife, with a particular love of elephants and birds. His love of photography was first sparked on a trip to Antarctica in 2006. BEN NEALE and KYLIE BERTRAM are the Australian couple behind

BEN NEALE and KYLIE BERTRAM are the Australian couple behind