It is a year since the BBC first screened Dynasties: Painted Wolves and nearly three since they stopped filming in Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe. Since then, the dynasty has struggled. Nicholas Dyer, who has followed these packs for the last seven years, tells the story of Tammy and the Nyamatusi Pack.

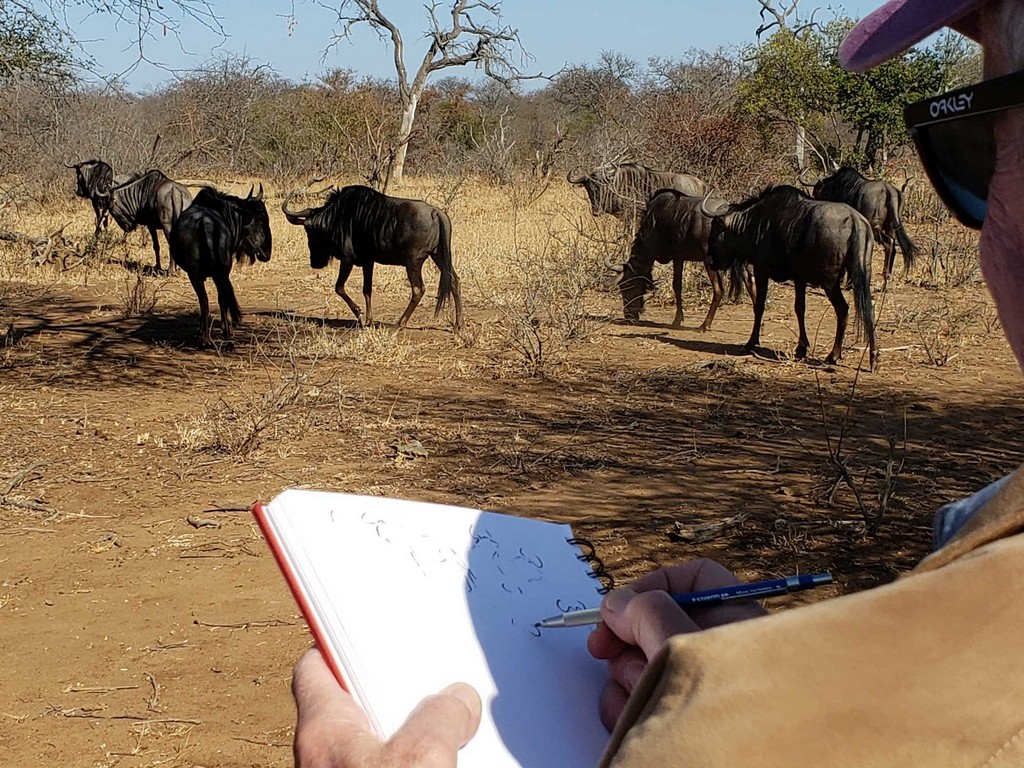

Six of the fourteen Nyamatusi Pack when they first formed – full of life and vigour. Tammy is the painted wolf on the left. © Nicholas Dyer

It has been a dark time for the painted wolves of Mana Pools.

Since the BBC finished filming Dynasties, it has been a story of intrigue, adversity and of a struggle that is all too familiar to this desperately threatened creature.

The BBC tells the story of Tait and her daughter Blacktip, who pushed her mother into the dangerous ‘Pridelands’. In doing so she overstepped her mark, resulting in several tragedies for both packs of painted wolves (also referred to as African wild dogs) and eventually the tragic loss of Tait to the jaws of a lion. In contrast, Blacktip’s pack were in retreat, licking their wounds.

The film ends, however, on an optimistic note, with the emergence of seven young females. All were Tait’s daughters who had escaped the lions and dispersed from Tait’s disintegrated pack. As the credits roll, they are seen to be ‘eyeing up’ seven healthy males, and we are left with the hope that this incredible dynasty is set to rebuild its strength and resume its dominance over the Mana floodplain.

A New Beginning

They did indeed form a pack. Peter Blinston – who is a good friend, head of Painted Dog Conservation (PDC) and co-author of our book Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog’s Life – and I first found them near the mouth of the Mana River in November 2015 just after they had got together. They were a geeky group yet to decide who would be the alpha female to lead them, and thus totally rudderless.

When the females met the males, close bonding rituals were essential and so much fun to watch. All photos © Nicholas Dyer

It was a bit like watching teenagers at their first school dance; they were all very excited but could not decide what to do with each other. They could never agree on what time to hunt, nor in which direction. But play, bond and muck around, relishing their new-found freedom they could do with abundance, and when they did eventually hunt, they were lethal.

? Leaderless, the new pack would sometimes just stare at the menu rather than launching an attack, but when they decided to hunt, they were stealth-like and lethal. Both photos © Nicholas Dyer

I don’t know if they knew, but they were related. The males were Blacktip’s sons and Tait’s grandsons; the females Tait’s daughters. This made the relationship incestuously close. As we watched them play, Peter and I tried to figure out the connection, and after much debate, the best we could come up with was aunts and step-nephews. Whatever it was, it would undoubtedly have been illegal in human terms.

Timmy was super-fast and would often lead the pack on the hunts © Nicholas Dyer

Tammy and Twiza

Eventually, Tammy, who I had known since a pup, emerged as the alpha – which was surprising as she was only two years old. A robust and healthy wolf called Twiza became her alpha male, and together they would lead the pack and become the sole breeding pair.

Eventually, Tammy became alpha female and chose Twiza as her alpha male © Nicholas Dyer

It was an exciting time for me. This was the fourth year I had been following these packs and the first time I had seen a new pack form. Spending all my time with them on foot had bonded me to them, far more than photographing from a car ever can. I now knew each individual by sight and had come to believe that they also recognised me. Not that I would ever interact with them in any way.

Tammy could have chosen Timmy, but he seemed more interested in food (left), and she gently out-sparred her rival Gemma for the position of alpha female (right). Both photos © Nicholas Dyer

Life at the den

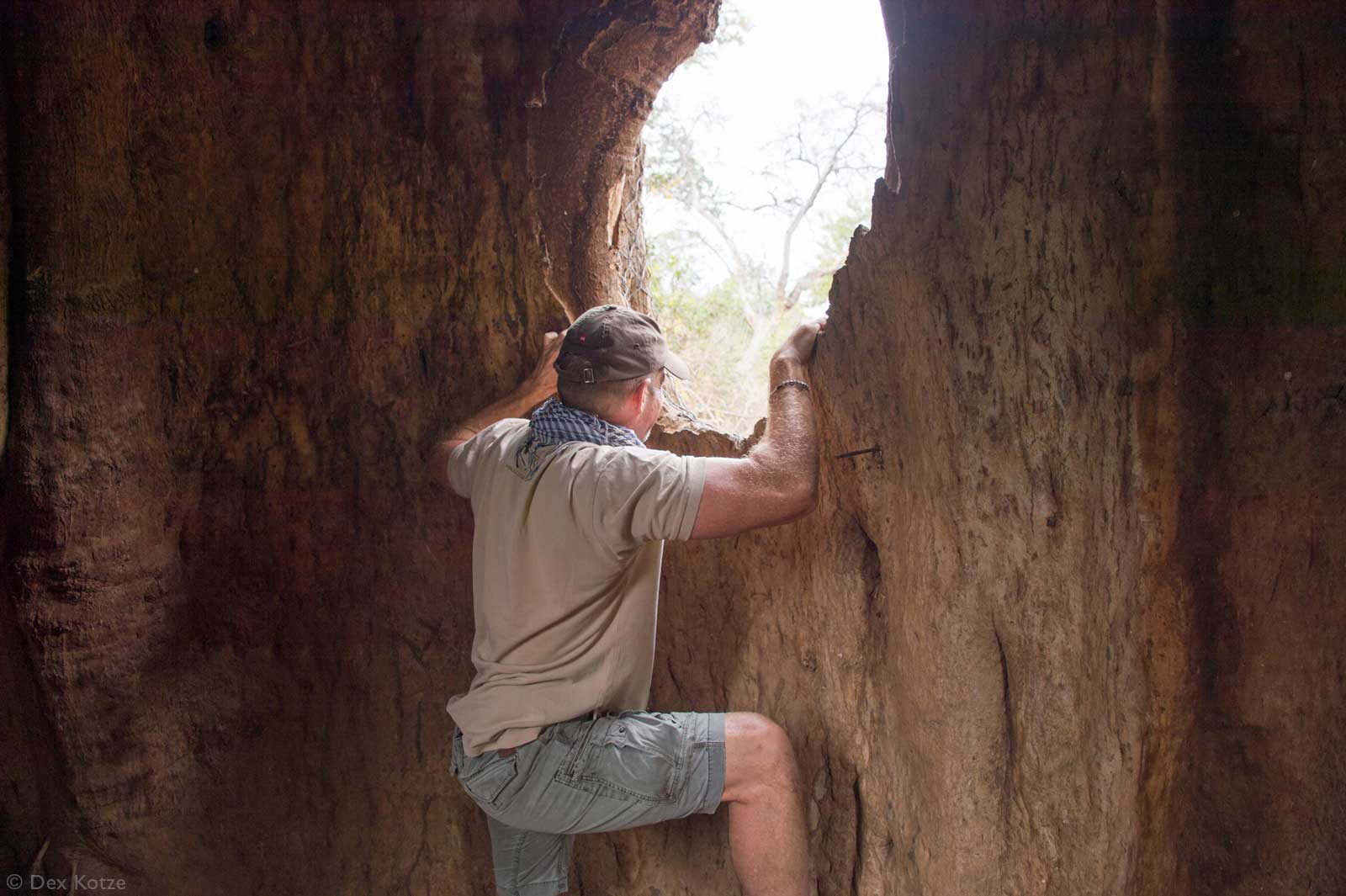

Tammy denned in the dense ‘jungle’ on the banks of the Mbera River in a very wild part of the park. It was named the ‘Pridelands’ by the BBC on account of a large pride of lions that dominate the area. After several weeks of patiently sitting in the riverbed near the den, two kilometres from the safety of my car, the painted wolves became increasingly used to my presence and eventually they allowed me to get close enough to view the den mouth.

All my photography is done on foot. Visiting and taking photos at the den required absolute respect, a lot of advice, patience, a great distance and a long lens © Nicholas Dyer

A den is a very sensitive place, and I was always concerned that I might disturb the pack. I was given strict guidance from PDC and ZimParks and acquired a lens configuration which gave me a reach of over 1,250 mm, enabling me to take photos far away from the den.

This meant I also needed a sturdy tripod. Carrying the heavy gear for several kilometres on my own each morning, walking along elephant tracks, through dense riverine bush, dodging grumpy elephants and wary of scratchy lion and cantankerous buffalo, was, to be honest, always terrifying.

But the reward was immense. Eventually, seven gorgeous black balls of fluff emerged from the den mouth, the pride of the pack.

Floppy-eared balls of fluff emerge from the den to the delight of every member of the pack. All photos © Nicholas Dyer

Every morning the pack set off to hunt. Tammy would follow them for a kilometre as if to see them off to work, and then come back to resume her motherly duties. The pack would return, bellies full and eager to feed Tammy and the pups. Tiny squeaks of joy would pierce the quiet bush as the pups delighted in regurgitated impala and baboon.

Very occasionally, Tammy would leave the den to hunt with her pack, perhaps to get some exercise. On return, she would delight in being the first to regurgitate for her pups. © Nicholas Dyer

It was magical spending so much time with these creatures and watching real characters emerge. There was Patrick, the gentle but strict headmaster, Tait Junior the caring maiden aunt, Taurai and Timmy, the strong warriors.

Kindly ‘headmaster’ Patrick holds the raptured attention of Tammy’s seven pups (raise your tails if you know the answer!) © Nicholas Dyer

Meanwhile, the pups developed their idiosyncrasies which multiplied the depth of my love for them. My favourite was Little Greedy Guts, who always came away with more than his fair share of food.

Little Greedy Guts always seemed to get more than his fair share of regurgitated impala and baboon © Nicholas Dyer

The big wide world

After three nurturing months it was time for the family to leave the den, to resume their nomadic lifestyle and lead the pups into the big wide world of Mana Pools – full of freedom and wonder, but also loaded with devastating dangers. Lion, leopard, hyena and crocodile all pose a continual mortal threat to painted wolves, especially to the pups.

But in spite of this, to experience the elation of the little pups when they finally shed the shackles of the den, filled me with hope and optimism – the survival of the species rested on their fragile but enthusiastic little shoulders. But in the back of my mind, I knew the odds – on average, only 50% of pups survive their first year.

Free from the confines of the den, the seven growing pups delight with curiosity at their newfound freedom, oblivious of the dangers of the big wide world © Nicholas Dyer

It was only weeks before the trouble started. One morning I found the pack, but could only count six pups. I never saw the other pup’s body, but hyena tracks were all around. Days later, renowned Mana guide Henry Bandure told me that another pup had been taken – he suspected a lion.

It was noticeable that after the loss of a pup, the pack became more attentive to the survivors and played with them with increased vigour. I wondered if this was to distract the pups from the trauma and their loss, or did it just impress on the adults the value of those that remained?

In November, when the rains began, I left the park and Tammy with only three pups out of the original seven. It was a harsh beginning for her first litter, but I noticed that Little Greedy Guts was still there.

After a violent and traumatic hyena attack, the painted wolf adults play with the pups to calm the pack down © Nicholas Dyer

A new year of hope

Mana Pools becomes virtually unnavigable during the rains, and the new tall grass makes it highly unwise to walk. But as I processed that season’s 60,000 photographs in sunny Plettenberg Bay, my thoughts were never far from the packs, battling through the ferocious summer storms.

I returned in April 2017, and late one evening, I found Tammy and her pack on the bed of the Cheruwe River. There were no pups in sight and through my binos, I could count only eight adults. Maybe the rest of the pack were lazing under a bush? The sun was about to kiss the Zambezi escarpment, and my car was a half-hour walk away, so I left, wary of nocturnal lions that become overfamiliar at dusk.

But a week of sightings confirmed that three more of the pack had died and only one of the pups had survived – a bouncy female called Ruby. It was not a great start for Tammy, but I took comfort in the fact that she was still very young, had a strongly bonded pack which had gained much experience.

Left: One little pup remained when the rains came. The bush turned a vibrant green, but life was about to get much tougher; Right: Ruby (on the left) was still alive when the rains started at the end of 2017, seen here playing with her aunt, Tait Junior. Both photos © Nicholas Dyer

That year, she denned again, and this time had five pups. When they were just old enough, she moved them deep into the densest bush far up the Mbera River. The walks to this den were the most terrifying I have ever done in Mana. If an elephant were five metres away, I would not have known. I only did it twice and each time with an armed guide. She would be safe there.

Again, Tammy successfully took the pups out of the den, but the attrition experienced in 2016 was to be repeated. By the time the rains came, there was only one pup left. It was sad to see this little guy alone, full of joy and mischief, but no playmates. The adults did their best to amuse him, especially Ruby, but it was not the same without siblings, and it felt like the life force was draining from the pack.

The pack weakens

In 2018 the attrition continued. When I came back after the rains, the little pup was no longer there, but somehow that was expected. More worrying was that four more of her adults were missing, including the yearling Ruby – with only seven painted wolves left, the pack was now half its original number… half its strength for hunting and defending against aggressors.

Despite these losses, Tammy successfully fell pregnant for the third time. She had seven pups to match her seven adults. Would they be able to take care of them this time?

Over the previous two years, I had put Tammy’s tribulations down to bad luck. But 2018 saw misfortune turn to tragedy. Before even leaving the den, more adults started succumbing to lion and hyena attacks. Patrick, my favourite wolf, went missing, Tait Junior never came back from a hunt, and before Tammy left the den, her mate Twiza had been killed.

By the end of the year, this once strong pack was reduced to only four adults and one surviving pup. Thomas Mutonhori, the brilliant PDC tracker, named the little guy Atten, in honour of Sir David Attenborough’s visit to Mana Pools earlier that year to top and tail the BBC Dynasties series.

Little Atten, named after Sir David Attenborough’s visit to Mana. Last seen when the rains came © Nicholas Dyer

The last hope

Atten was still alive when the rains came, but just like the pups that went before him, he did not survive them, although Tammy and her four remaining males did. Taurai, the strongest of the males looked ancient, his Mickey Mouse ears shredded by a lifetime of skirmishes. He was perhaps too old to become an alpha, but his younger brother Jimmy successfully mated with Tammy and earlier this year she incredibly had ten pups, denning in the Wilderness concession at the eastern edge of the park.

Was 2019 to be Tammy’s year? A bumper brood but only four painted wolves to provide and protect. In early September, soon after they had left the den, there was a savage hyena attack in which all but one of Tammy’s pups were killed. Tammy herself sustained a massive wound to her right shoulder. She struggled on for a few days, Jimmy, Taurai and Timmy nursing and feeding her.

Thomas found her body a few days later, the rest of the pack sitting nearby. It was a tragic and violent end to a beautiful alpha who started her life with so much promise. Only one little pup is surviving today, a fragile thread to take on her legacy, with three tired males to protect him.

Tammy (right) as a pup in Tait’s Vundu Pack, on her first hunt in November 2014. In the background is Victoria, her elder sister by three years. © Nicholas Dyer

Epilogue

Back in September 2014, I watched a vicious hyena attack on Tait’s Vundu Pack. A little pup stood in front of me, transfixed as a full-grown spotted hyena bore down on her, intent on her destruction. The little pup skilfully side-stepped its powerful jaws before three other wolves could see it off. That little pup was Tammy, and she survived that attack by a thread.

Tammy was lucky then, but in life, she was not so fortunate. I described her in my book as “the promising Tammy”, but that promise never came to fruition.

Tammy as a pup dodging the ferocious jaws of a spotted hyena © Nicholas Dyer

I had known Tammy since she was a pup and had grown very attached to her. Tammy’s life was a sad one, but what makes it tolerable for me is that her death was natural. Lions and hyenas are the painted wolves’ nemesis in a constant battle for dominance within a shrinking landscape, though some protected areas like the Maasai Mara offer wildlife photography safaris to observe these interactions.

What is far harder to bear is to see packs wiped out through our destructive human tendencies; through snares, road kills and disease. In the relative paradise of Mana Pools, at least we can celebrate that all wildlife can play out its natural dramas, far from the worst ravages of man.

The pack on alert for potential prey and predators © Nicholas Dyer

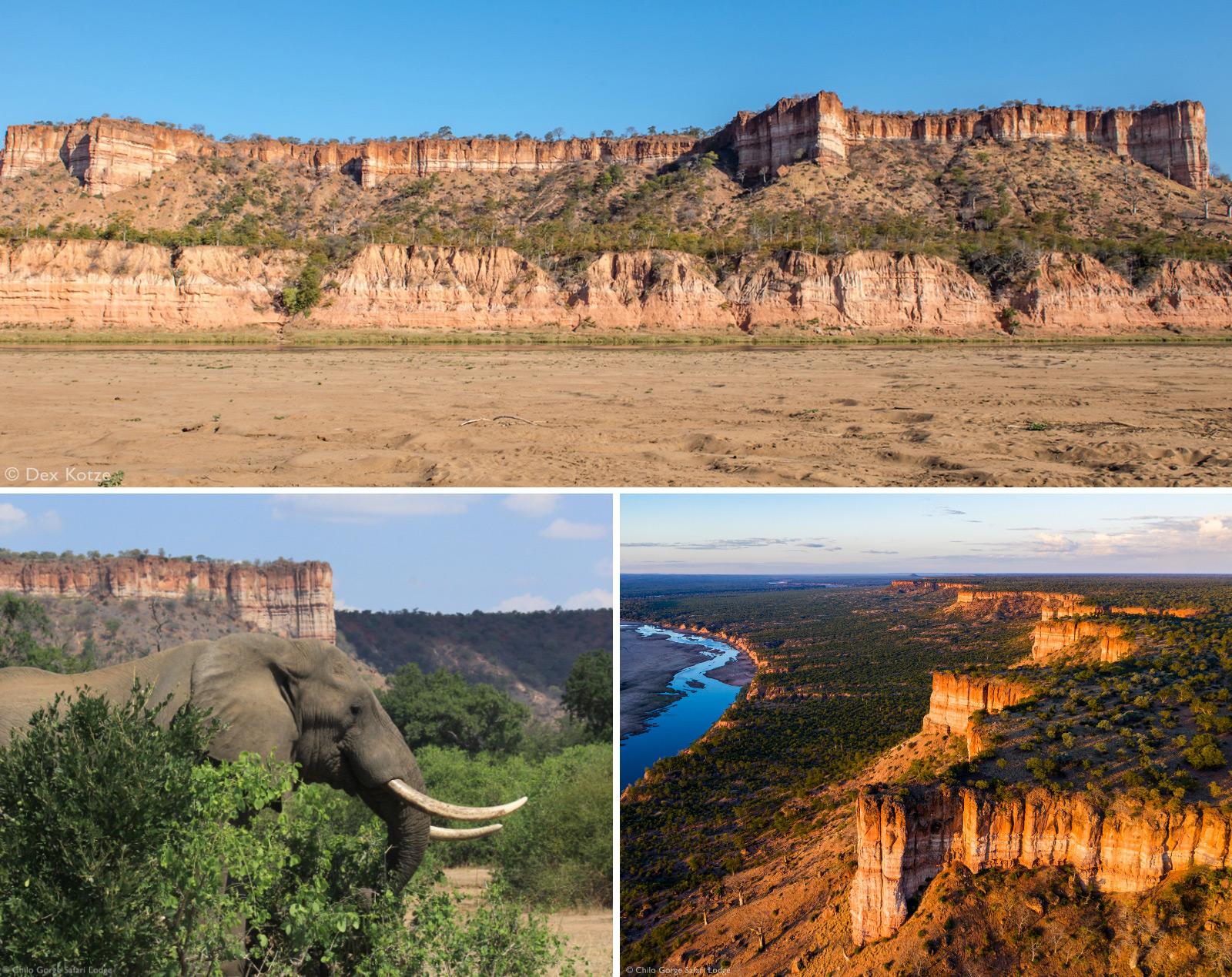

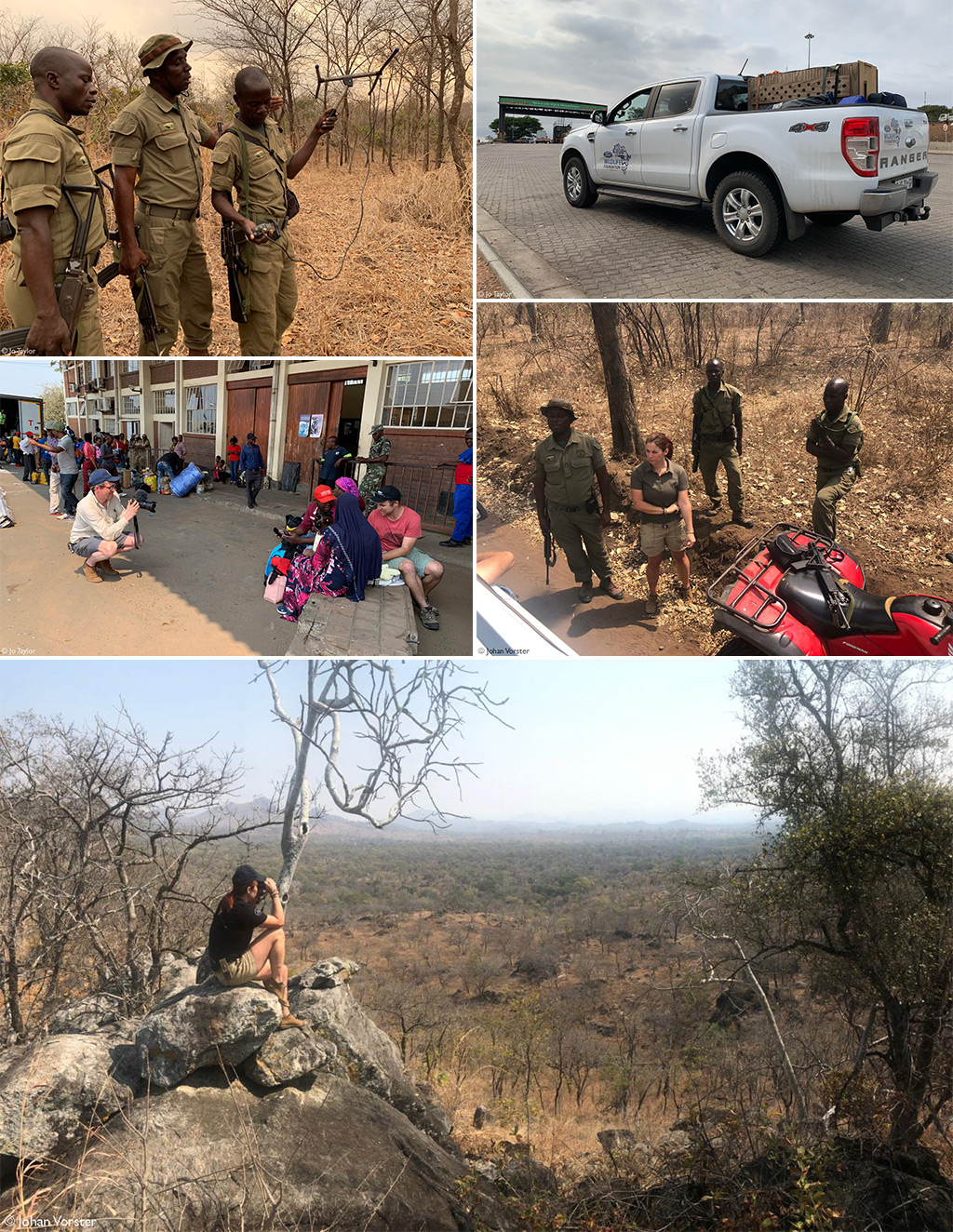

MANA POOLS NATIONAL PARK

Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe is a World Heritage Site and one of the last true wildernesses in the world. It is the only park in Africa where you are allowed to walk alone, albeit at your own risk. It is also one of the best places to view painted wolves. Many of the photographs in this article were taken at the den. Nick visited the dens under the guidance and supervision of Painted Dog Conservation (PDC) and ZimParks in preparation for the campaign to raise global awareness of this endangered species. Denning season is a sensitive time for the painted wolves and Nick, and PDC would strongly discourage den visits for reasons unrelated to conservation. They would, however, strongly encourage visitors to thoroughly enjoy painted wolf sightings but always treat them with respect and observe the sensible Mana Pools’ “Code of Conduct”.

ABOUT THE PAINTED WOLF FOUNDATION

The Painted Wolf Foundation (PWF)was set up by Nicholas Dyer, Peter Blinston and leading conservationist Diane Skinner. It aims to raise awareness about this much threatened and ignored species and support organisations that conserve painted wolves on the ground. PWF is a UK-registered charity (Number 1176674).

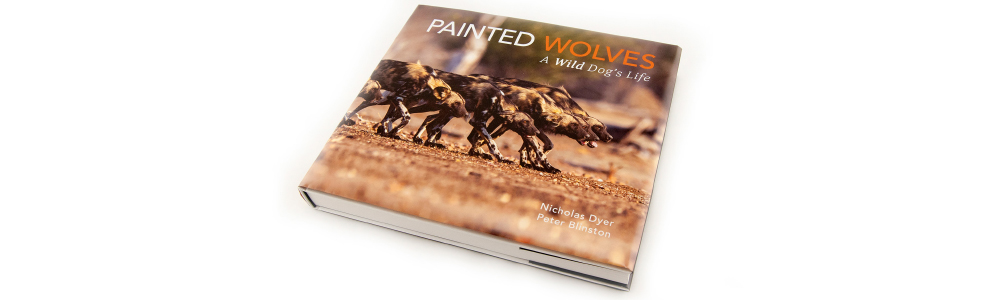

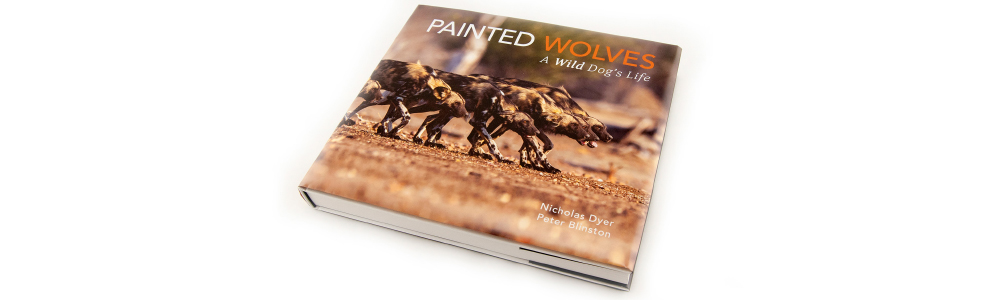

THE BOOK

PAINTED WOLVES: A Wild Dog’s Life

The painted wolf is Africa’s most persecuted predator. It is also its most elusive and enigmatic. For six years, Nick has been tracking and photographing them on foot in the Zambezi Valley.

For twenty years, Peter has been doing all he can to save them from extinction. If there is one book that will let you into the secret world of the painted wolves, this is it, expertly narrated across 300 pages and illustrated with over 220 stunning images.

“Wildlife photographer Nick Dyer and conservationist Peter Blinston have crowdfunded a new book, Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog’s Life, which takes the reader on a fascinating journey into the lives of the painted wolves and what is being done to save them. It’s a beautiful book full of interesting facts and stunning photos, which I hope will raise the profile of the animals.” ~ Sir Richard Branson

Buy the book here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Nicholas Dyer

Nick grew up in Kenya and after careers in finance and marketing in the UK, has found a new métier as a wildlife photographer, author and conservationist with a deep passion for painted wolves. He has spent much of the last six years photographing the packs of Mana Pools on foot while living in his tent on the banks of the Zambezi. He is a founder of the Painted Wolf Foundation and frequently gives talks around the world on this neglected species. He was an award winner in the 2018 NHM Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition and leads specialist photographic safaris in Mana and across Africa so that people can experience this stunning creature. See more of his photography at www.nicholasdyer.com, and follow him on his Facebook and Instagram page.

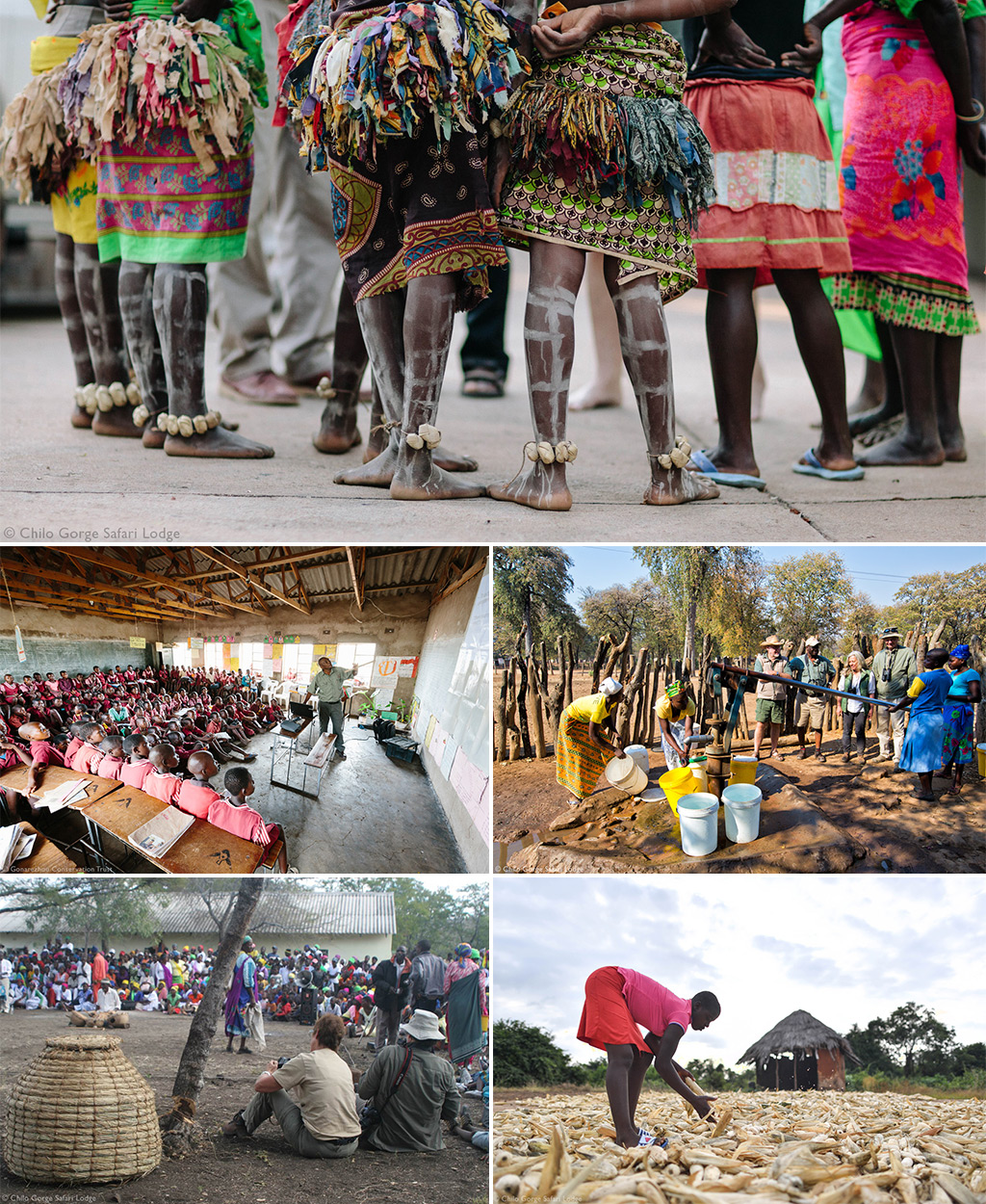

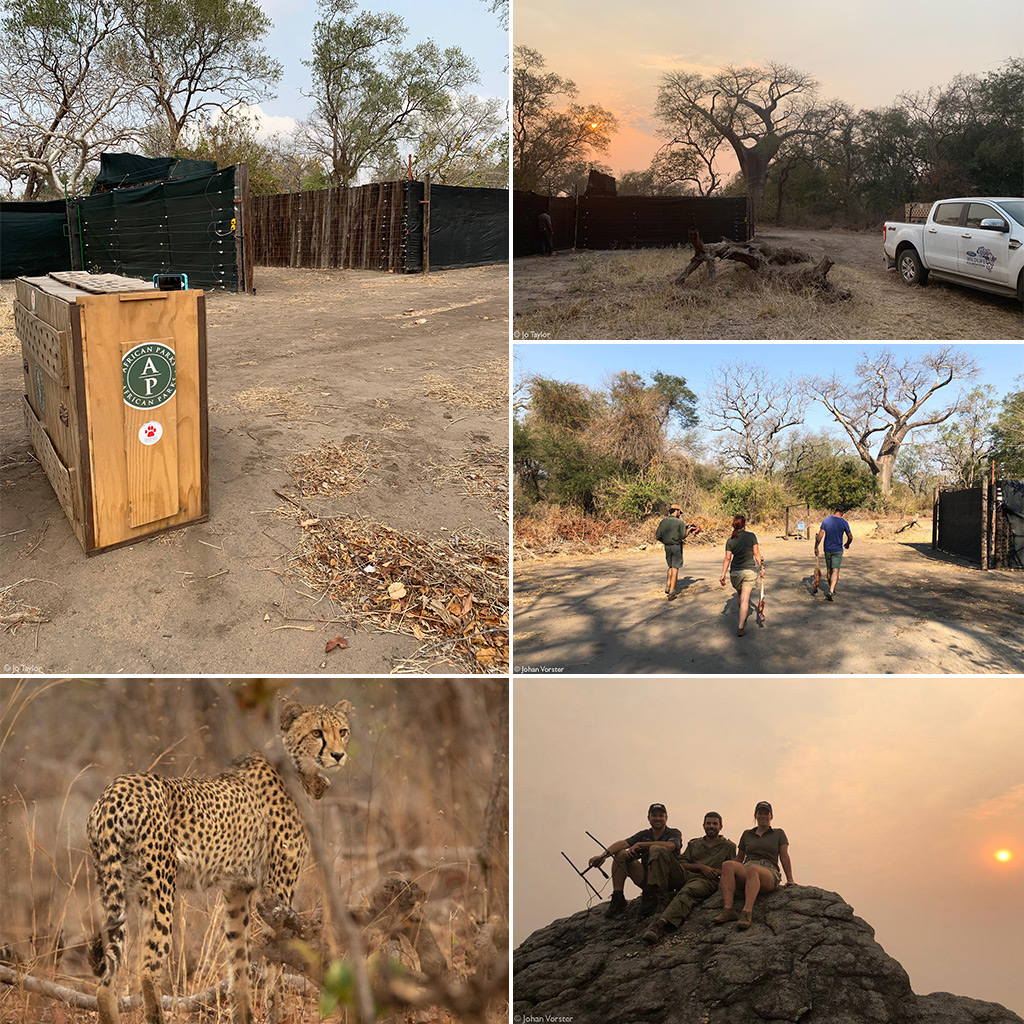

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

Eraine holds a degree in Microbiology, and it is during the zoology part of her course that she learned more about spiders, prompting her interest in spider photography. For the past two and a half years, she has spent most of her free time searching for and photographing these interesting creatures. To see more of her photographs take a look at her

Eraine holds a degree in Microbiology, and it is during the zoology part of her course that she learned more about spiders, prompting her interest in spider photography. For the past two and a half years, she has spent most of her free time searching for and photographing these interesting creatures. To see more of her photographs take a look at her

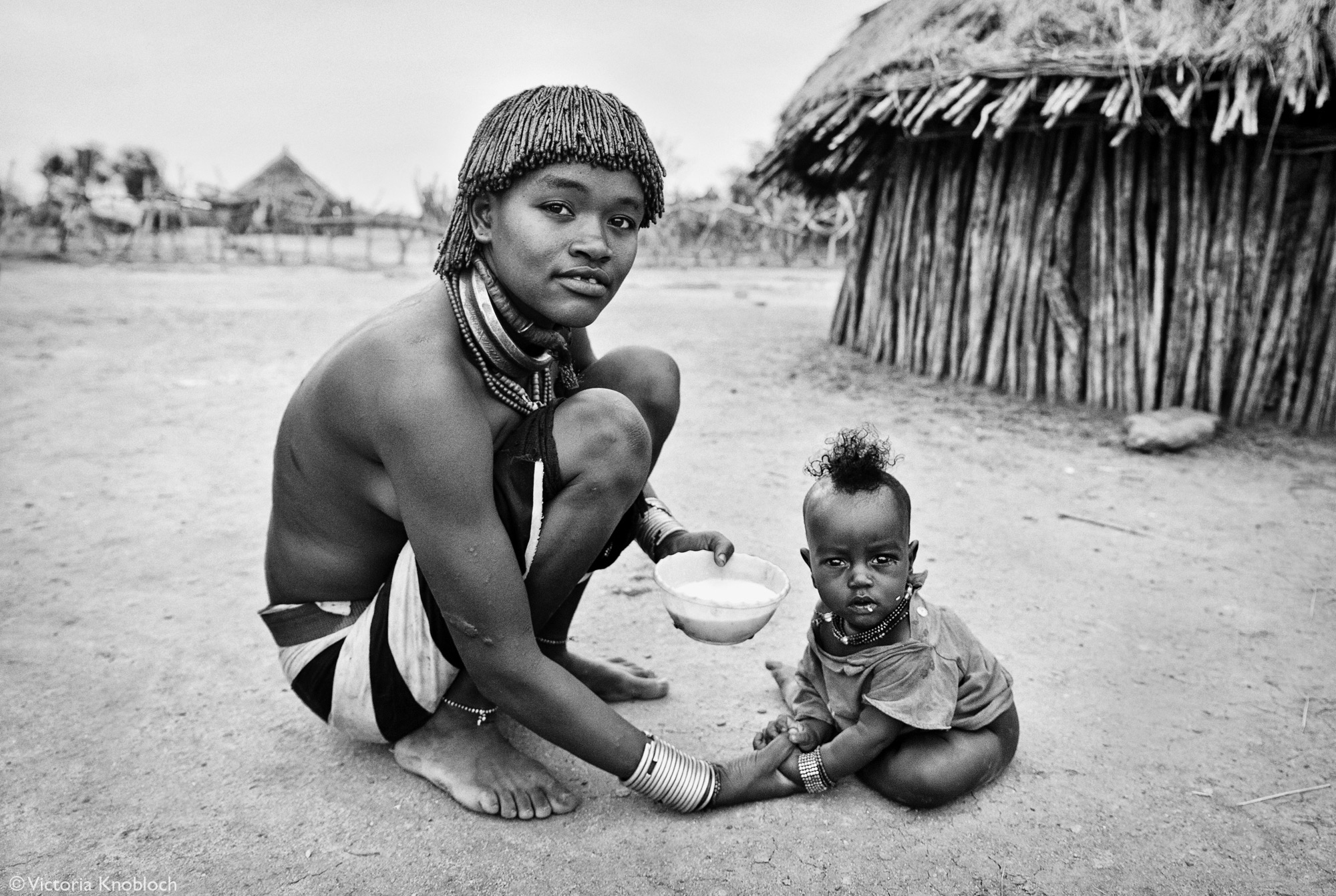

Victoria Knobloch is a German photographer who concentrates on black and white portrait art and documentary work. Her work embraces the fields of vanishing cultures, ancient traditions and contemporary cultures, with the human element as the continuous thread. Furthermore, she is always in search of tranquillity, beauty and meditative landscape moods and approaches them in a poetic way. With this, she invites the viewer to pause, contemplate, observe and reflect, if only for a brief moment. You can see more of her works

Victoria Knobloch is a German photographer who concentrates on black and white portrait art and documentary work. Her work embraces the fields of vanishing cultures, ancient traditions and contemporary cultures, with the human element as the continuous thread. Furthermore, she is always in search of tranquillity, beauty and meditative landscape moods and approaches them in a poetic way. With this, she invites the viewer to pause, contemplate, observe and reflect, if only for a brief moment. You can see more of her works

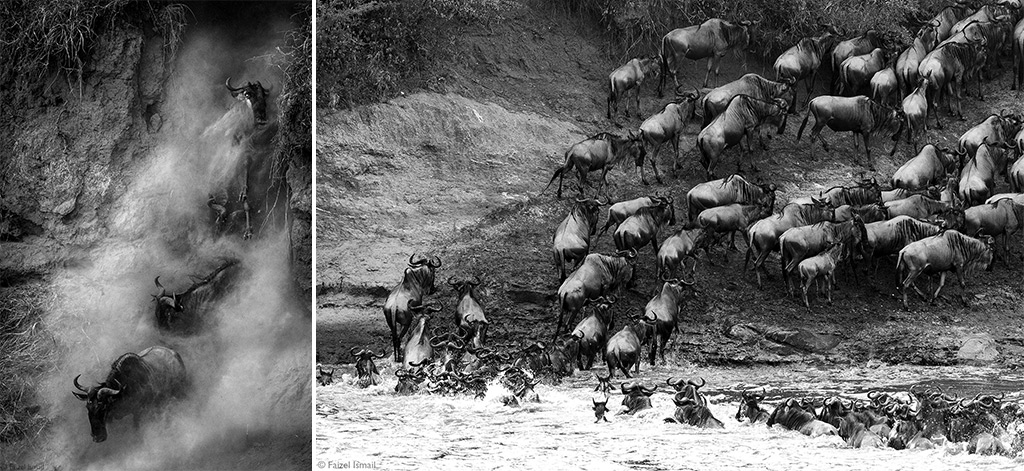

Faizel is a modern-day explorer, wildlife photographer and conservationist. He was born and raised in the town of Rustenburg, in the heart of beautiful South Africa, but his travels have taken him far and wide, and he currently resides in the United States.

Faizel is a modern-day explorer, wildlife photographer and conservationist. He was born and raised in the town of Rustenburg, in the heart of beautiful South Africa, but his travels have taken him far and wide, and he currently resides in the United States.

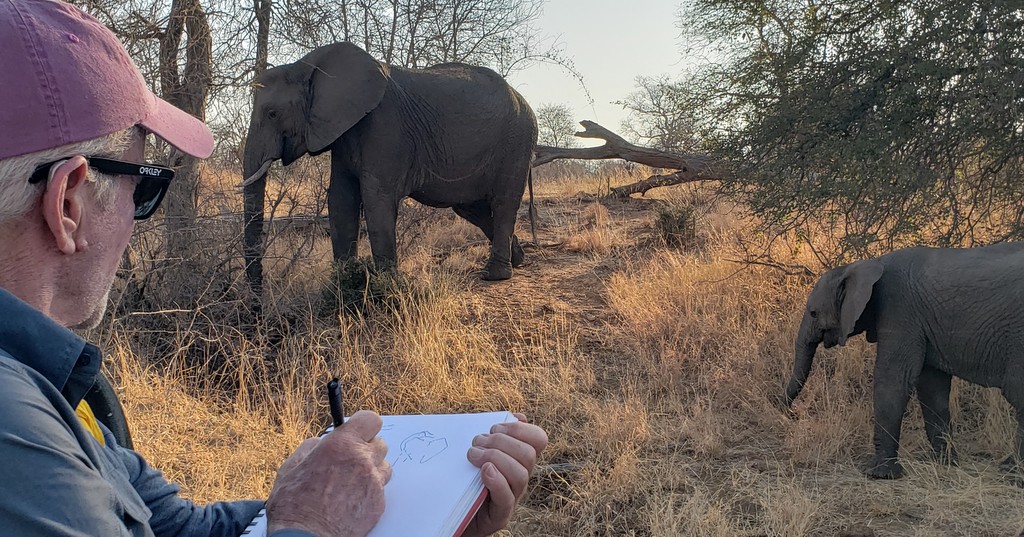

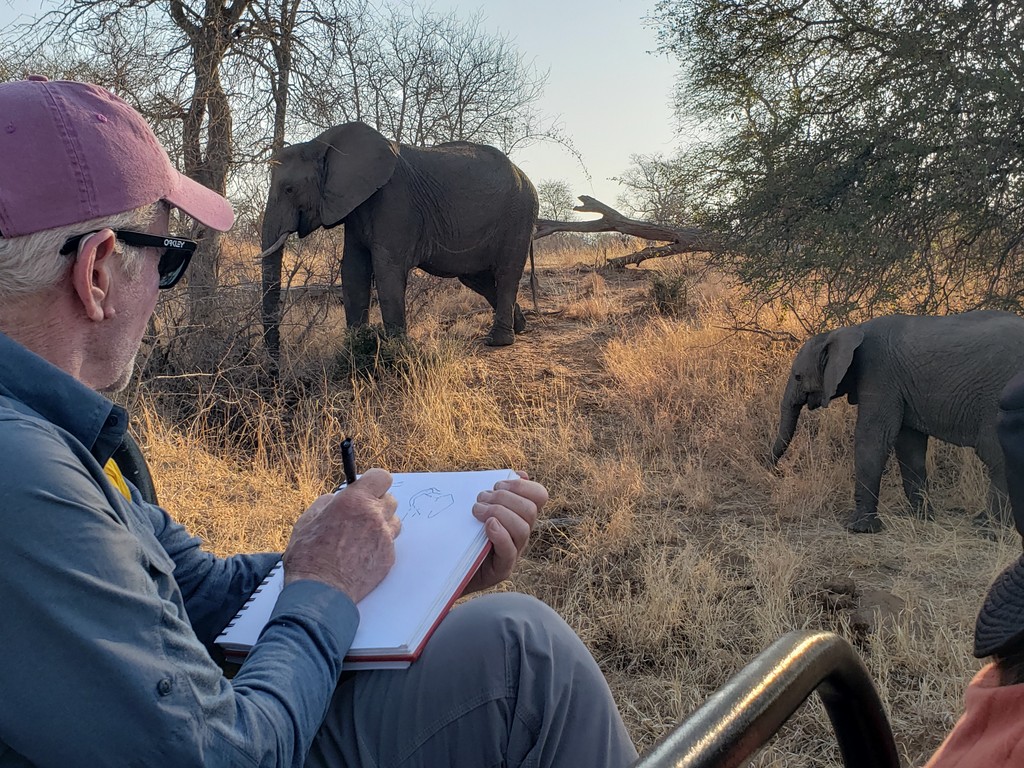

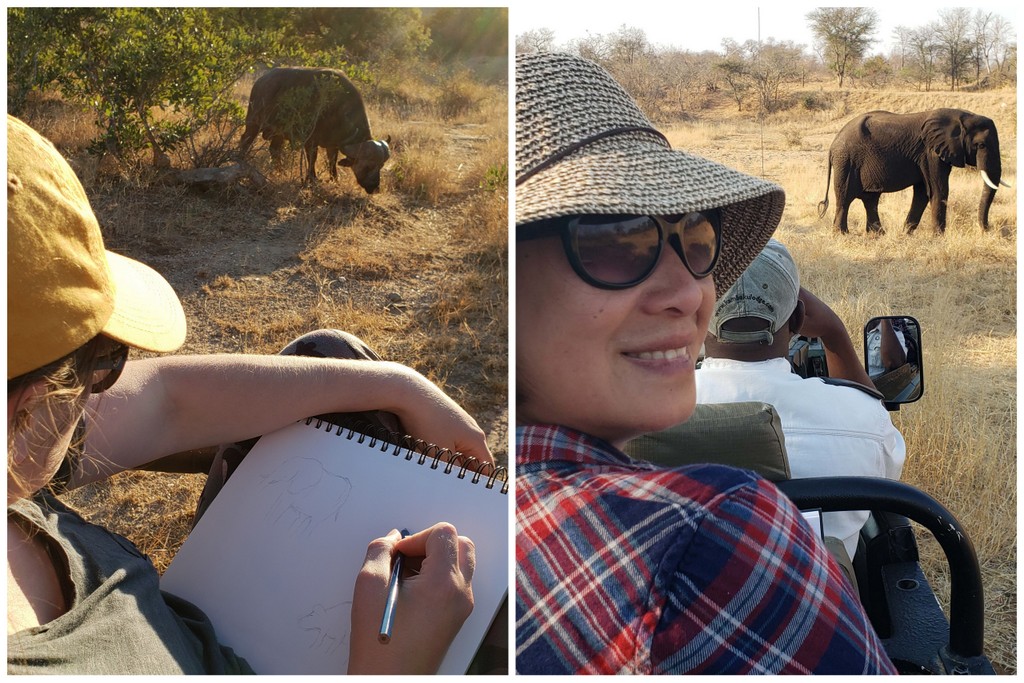

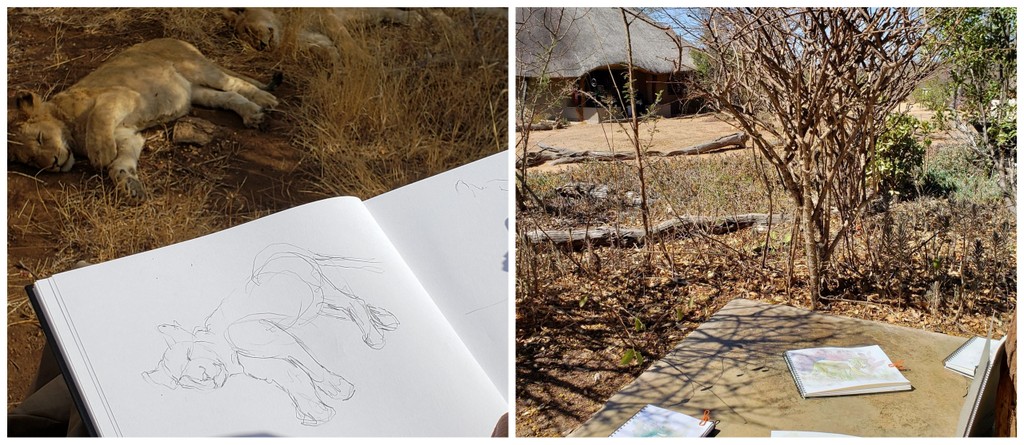

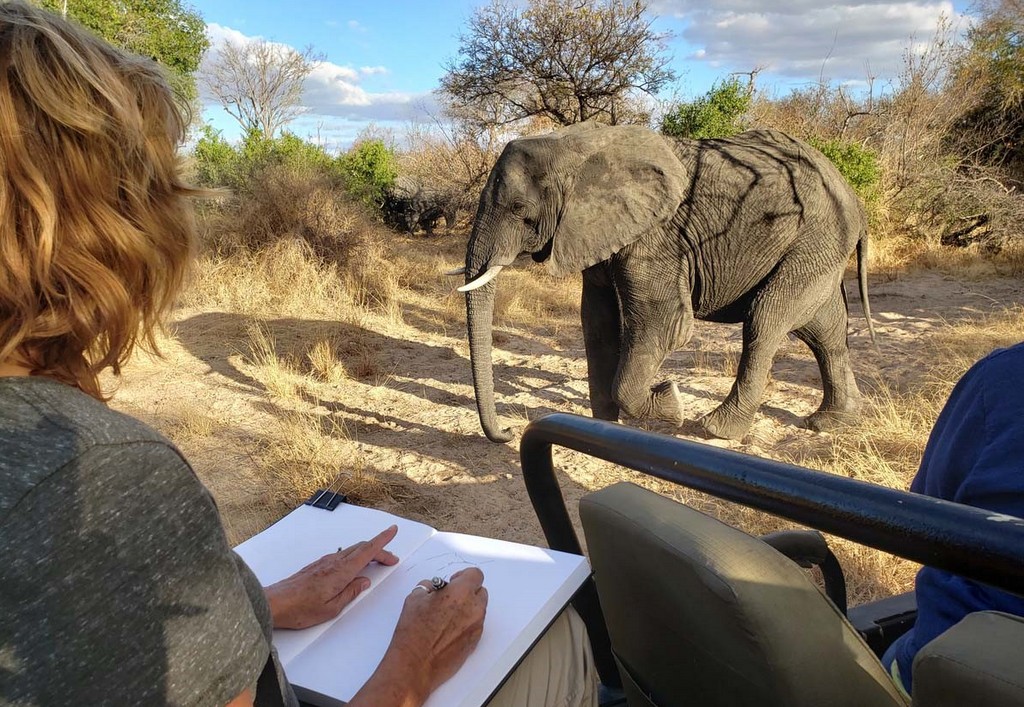

Expressing herself with found objects, palette knife and paintbrush, Lin Barrie believes that the abstract essence of a landscape, person or animal can only truly be captured by direct observation. She immerses herself in her subjects, whether observing African night skies, sketching rhinos drinking at a favourite waterhole, watching African wild dogs and their pups, or capturing the mood of an abstract landscape or traditional dance. She is fascinated by the synergies between elements of landscape, people and animals, such as the flow of water which becomes fish, the texture of baobab skin which so closely resembles that of elephants’ limbs, the shapes of monumental rock outcrops which take human or animal forms, plants which echo human parts, animal totems and people. You can see more of her artwork on her

Expressing herself with found objects, palette knife and paintbrush, Lin Barrie believes that the abstract essence of a landscape, person or animal can only truly be captured by direct observation. She immerses herself in her subjects, whether observing African night skies, sketching rhinos drinking at a favourite waterhole, watching African wild dogs and their pups, or capturing the mood of an abstract landscape or traditional dance. She is fascinated by the synergies between elements of landscape, people and animals, such as the flow of water which becomes fish, the texture of baobab skin which so closely resembles that of elephants’ limbs, the shapes of monumental rock outcrops which take human or animal forms, plants which echo human parts, animal totems and people. You can see more of her artwork on her

“Once Africa has touched you, life will never be the same”. I was born and raised in England, but somehow fate decided my destiny was Africa. I am fortunate to have developed a lifestyle from my two greatest passions – wildlife and photography – which make for the happiest of marriages! I gave up a lucrative career in high-tech to follow my calling and have never looked back. I have great faith in the power of visual media and its ability to educate, inspire, create awareness and shape change. My raison d’etre is to be an ambassador for all things wild. I hope that my enthusiasm and photography will act like ripples in a pond that encourage others to protect, conserve and sustain this beauty for future generations. I am still unsure where this path will lead, but I enjoy the journey of following the roads less travelled. See more of Charlie’s work on

“Once Africa has touched you, life will never be the same”. I was born and raised in England, but somehow fate decided my destiny was Africa. I am fortunate to have developed a lifestyle from my two greatest passions – wildlife and photography – which make for the happiest of marriages! I gave up a lucrative career in high-tech to follow my calling and have never looked back. I have great faith in the power of visual media and its ability to educate, inspire, create awareness and shape change. My raison d’etre is to be an ambassador for all things wild. I hope that my enthusiasm and photography will act like ripples in a pond that encourage others to protect, conserve and sustain this beauty for future generations. I am still unsure where this path will lead, but I enjoy the journey of following the roads less travelled. See more of Charlie’s work on