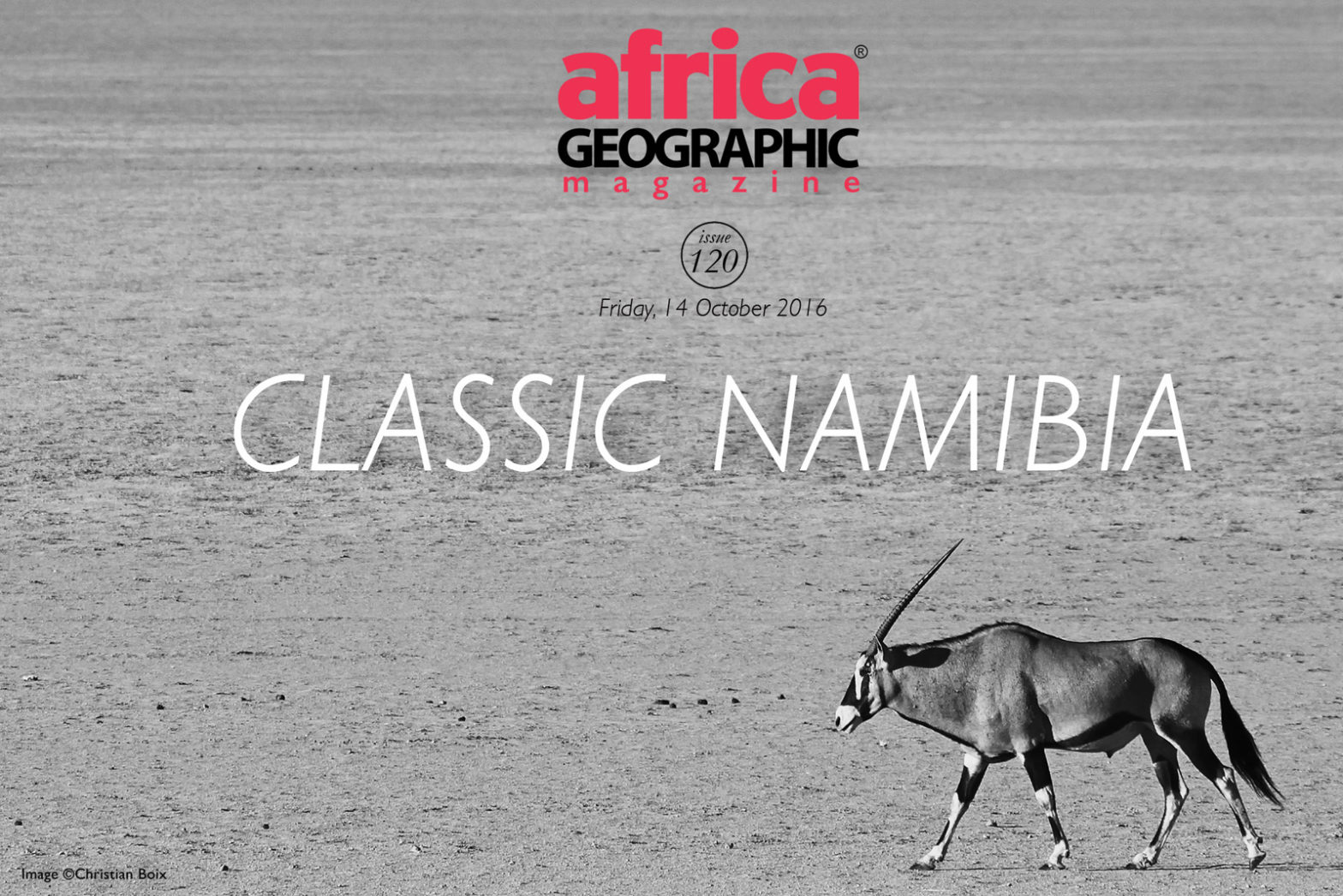

Namibia is a land of stark contrasts, and a typical visitor can expect to be left in awe by its magnificent polarities – from an abundance of wildlife around waterholes in Etosha to withered tree stumps between the dunes in Deadvlei.

The country is perhaps best known for its vast landscapes, blue skies, sand dunes and endless white gravel roads. Protecting some of Africa’s most untouched wildernesses, offering unique safari experiences. It is also an excellent destination for photographers and wildlife lovers. All creatures great and small make an appearance in Namibia’s sandy nooks and crannies – from chameleons by the roadside and meerkats on the gravel plains, to black-maned lions and desert-adapted rhinos or elephants roaming massive expanses of semi-arid terrain.

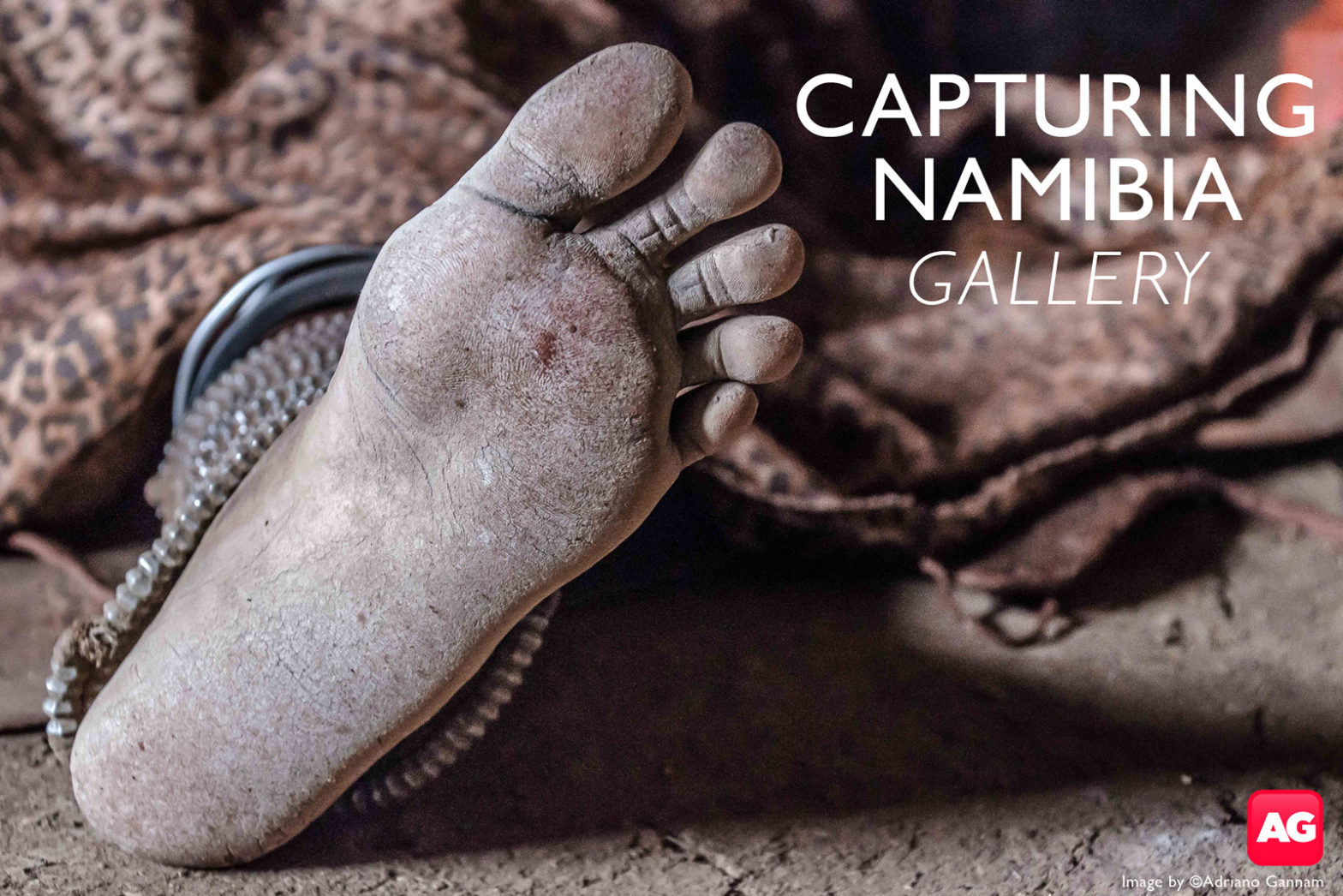

And on a two-week trip AG director Christian Boix and six guests from Brazil and Canada crisscrossed this land in search of some of its most iconic photographic highlights. Armed with tripods, lenses, filters, hats, and oodles of suntan lotion, they ventured forth into its wildernesses with a thirst for quirky light, moonless nights, impressive vistas, beautiful people, great wildlife sightings and cold Windhoek lager.

This gallery showcases some of the highlights of their journey to most of the hotspots in this country that offers a little something for everyone.

? The iconic dunes of Sossusvlei ©Christian Boix

Nestled in the largest tract of conservation land in Africa – an impressive enough reason to visit the Namib-Naukluft National Park – lies one of the continent’s true geological gems. Sossusvlei is home to some of the most spectacular natural sand dunes in the world and is undoubtedly one of the most photographed desert landscapes in Africa. A single picture of Sossusvlei’s stark natural beauty – silhouetted camelthorn trees against a glowing morning backdrop of a towering, curvaceous red dune – can capture the essence of Namibia and what it has to offer. Nowhere else in Africa does a desert landscape convey such raw, aesthetic beauty than in Sossusvlei.

For a fantastic view of this magnificent landscape, a climb up Big Daddy or Dune 45 is well worth the hot, sweaty slog. But for an even higher viewpoint, you might want to consider a sunrise hot air balloon safari!

Finding a quiet spot to yourself in this massive landscape is not too hard, despite the hundreds of tourists that visit it daily. Sitting on a dune silently will soon reveal a gamut of critters, which eke out an existence in this seemingly dead land. The sound of a desert breeze, or the gentle crinkle of sand on the move, is often dimmed by the sound of your blood rushing through your eardrums. Vivid colours, wrinkled rocks, polished logs, and at times the sweet scent of acacia blooms, encapsulate the true essence of this magical spot.

Also worth experiencing in the area is the Sesriem Canyon – the gateway to Sossuvlei. Formed over many millennia by the Tsauchab River, the canyon is about a kilometre long and 30 metres deep in places. It is home to some of the most captivating rock formations in Namibia and is also one of the only places in the region that holds water non-perennially.

While a trip to Sossusvlei is essential on your Namibian itinerary, it can be challenging to access without a 4×4 vehicle. Access to both Sossus and Deadvlei can only be attempted by 4×4 travellers, while 2×4 travellers should park their cars and take the shuttle that covers the last five kilometres of deep sandy tracks. In fact, why not walk the final stretch and take in the spectacular scenery, sounds and smells no matter what vehicle you have?

? Making friends while sea kayaking in Walvis Bay ©Christian Boix

About 30km south of Swakopmund lies a busy harbour town on the edge of a wide lagoon that serves as the perfect hibernation area for thousands of shorebirds and migratory bird species. It offers a fantastic source of food for innumerable pelicans, flamingos, and terns – more specifically the diminutive and endemic Damara terns – while the booming fishing, cargo and sea salt industry provides many of the town’s residents with their daily bread.

Walvis Bay has always offered a gamut of exciting activities centred around its lagoon, dunes and the nearby Sandwich Harbour. A plethora of food and accommodation options have sprouted as a result. You can even expect to find a desert golf course, catamaran trips, dolphin cruises and historian quad bike rides of the dunes at your fingertips.

A climb up Dune 7 on the outskirts of town will reward you with splendid views of the lagoon, but if you want to get acquainted with those that live in its waters, then dolphins, whales and Cape fur seals can be found splashing around the black-and-white Pelican Point Lighthouse. The best way to make friends with the colony of seals is by a spot of sea kayaking, which will give you the chance to get up close and personal with these thick-pelted divers.

? The sun sets over the pier in Swakopmund ©Christian Boix

Sandwiched between the Atlantic Ocean and the Namib Desert lies a coastal oasis that feels like a surreal remnant of a bygone colonial era. Distinctly German in flavour – thanks to its residents, visitors, architecture and cuisine – it’s the perfect place to enjoy a sunny, if somewhat cool and windblown, stroll down a seaside promenade before tucking into stewed venison spätzle.

As Namibia’s most popular holiday destination, it’s not only our Baltic friends who are attracted to Swakopmund, but it’s also the place-to-be for adrenalin junkies. From skydiving and surfing to living desert tours and camel rides, the range of activities on offer is responsible for the town’s reputation of being the adventure capital of Namibia. There’ll never be a dull moment here, whether you wish to wander along the iconic pier or throw yourself out of an aeroplane over the dunes.

? A photographer’s dream at Spitzkoppe ©Christian Boix

Spitzkoppe, an awesome granitic inselberg, rises out of the Namib’s barren landscape. It has become an iconic landmark of Damaraland and is recognised by many granite-climbing junkies all over the world as the “Matterhorn of Africa”.

Most who journey here are content to stand in awe at the 100-million-year-old formations – around which are several San bushman rock art sites to explore – but, for the more intrepid travellers, the peaks are begging to be climbed. A Spitzkoppe ascent is not to be made without adequate climbing gear or experience and, at 700 metres above ground level, it is not for the faint of heart either.

Part of the Erongo Mountain range, Spitzkoppe is a remnant volcanic plug that now stands as one of the most celebrated mountains in Namibia. There are several other features of the range in the Damaraland region that are well worth adding to your itinerary. The Brandberg or ‘fire mountain’ gets its name from the burning-red hue glowing on its face at sunset – a spectacular time of day in this region. The Petrified Forest is a mystical forest of 200 million-year-old fossilised trees that were uprooted during a flood and have since been revealed by erosion as a striking spectacle of the landscape. God’s Finger, Organ Pipes, Burnt Mountain, and a never-ending list of other incredibly beautiful sights and formations, await around every turn of the road.

No matter what type of traveller you are or what you’re looking for in your Namibia experience, you’re bound to consider Spitzkoppe to be one of the most striking landscapes on your trip.

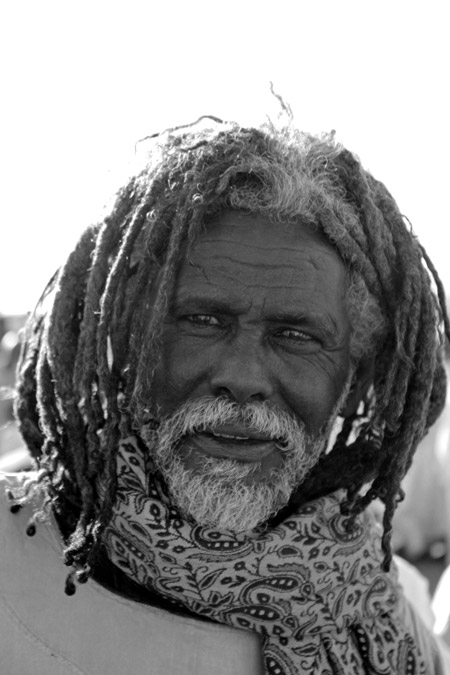

? A Herero woman in traditional dress in Damaraland ©Adriano Gannam

The Herero are a fascinating tribal group, known mostly for their antiquated clothing, which was introduced by Christian German settlers who sought to convert the tribe and clothe them in the European fashion of the times. This has since become a distinguishing mark of their identity despite the war that these same colonisers waged on them at the turn of the 20th century, which led to the death of about three-quarters of the tribe. By 1905 it is estimated that only 16,000 Herero remained, but today there are about 100,000 living mainly in the central and eastern parts of Namibia.

It is argued that the Herero’s choice to continue wearing their formal attire is a symbol of defiance and survival. The Herero women tend to wear traditional floor-length dresses from their wedding day onwards, and the men dress up at ceremonies in the uniforms of their European oppressors. This is said to be a way of honouring their ancestors who would wear the uniforms of German soldiers that they killed during their genocide. The Herero are proud cattle farmers who, before colonial times, prospered in the central grassland areas where there was ample grazing opportunity. They continue to measure their wealth in cattle – the importance of which is also reflected in the women’s headwear and dances. Their hats are designed to resemble cow horns, which get smaller as they get older as a symbol of their decreasing fertility. And during celebrations they perform the cow dance, which involves stamping feet, kicking up dust, and imitating the upraised horns and swaying movements of cattle.

If you’re in Namibia at the end of August, then it’s worth trying to head to the Herero festival, which is held in Okahandja on Maherero Day.

? Dancing kudu rock art at Twyfelfontein ©Christian Boix

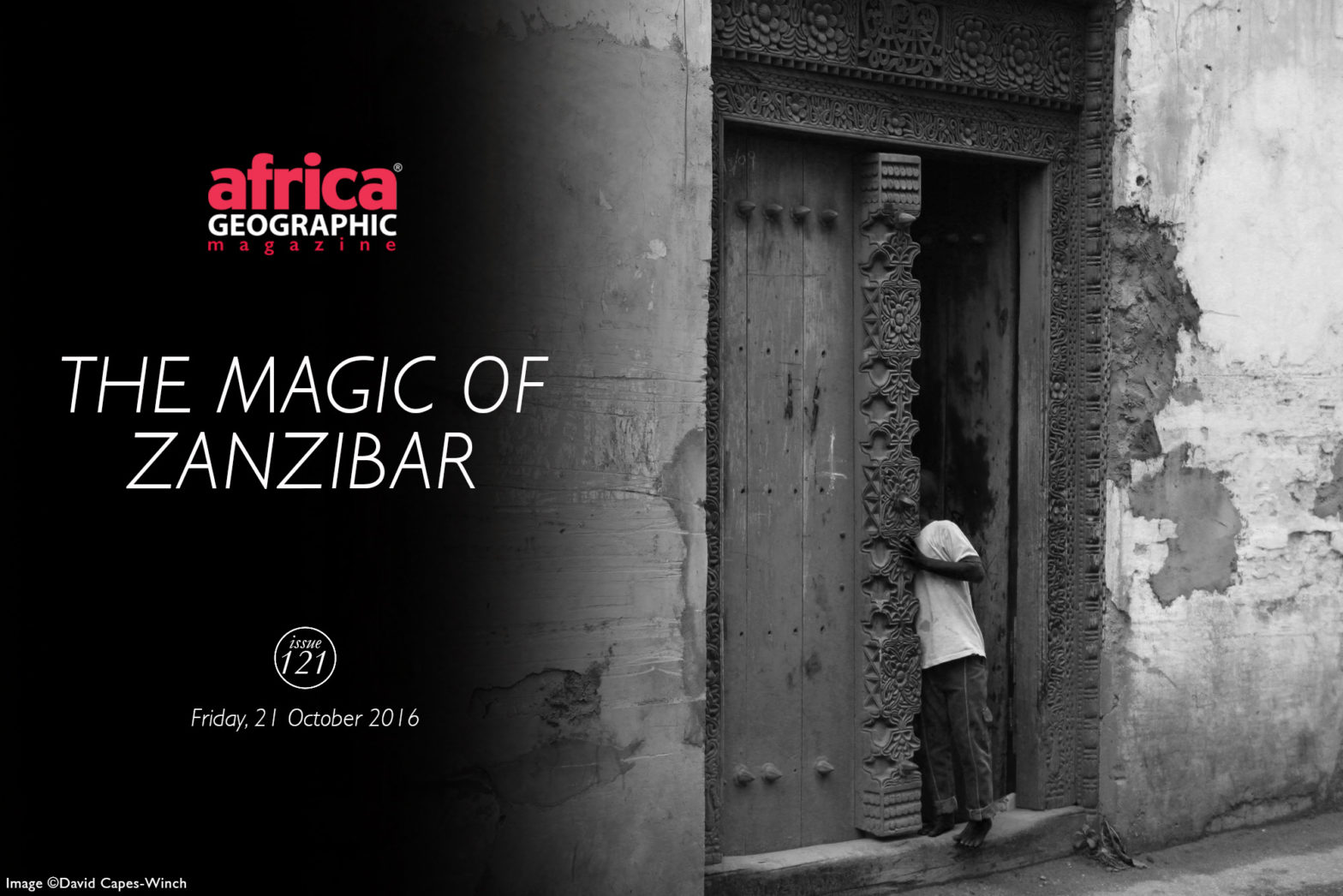

The oldest example of bushman art in Namibia is thought to date back 28,000 years. And in Twyfelfontein or /Ui-//aes you will find one of the largest concentrations of rock engravings on the continent. Most of these preserved petroglyphs feature rhinos, but elephants, ostriches and giraffes are also well represented, as well as drawings of humans and animal footprints.

Some of these engravings and red ochre paintings date back to the Stone Age, and the site at Twyfelfontein provides an extensive record of rituals and economic practices of San hunter-gatherer communities in this part of Southern Africa before Damara herders and European colonialists moved in.

Separating it from the rest of the country’s rock art sights, Twyfelfontein truly feels like one of the world’s most ancient universities. The stories, engravings and meticulous detail represented in the sandstone are testimony to a very elaborate and active teaching process. Waterhole maps depicting game trails, footprints of different animals, and drawings of coastal creatures, are all evidence of what must have been an incredibly lively and enthusiastic lecture – The Science of Tracking!

Apart from one small engraved panel, which was relocated to the National Museum in Windhoek at the start of the 20th century, none of the rock art has been removed or tampered with.

? A Himba dance in Kaokoland ©Christian Boix

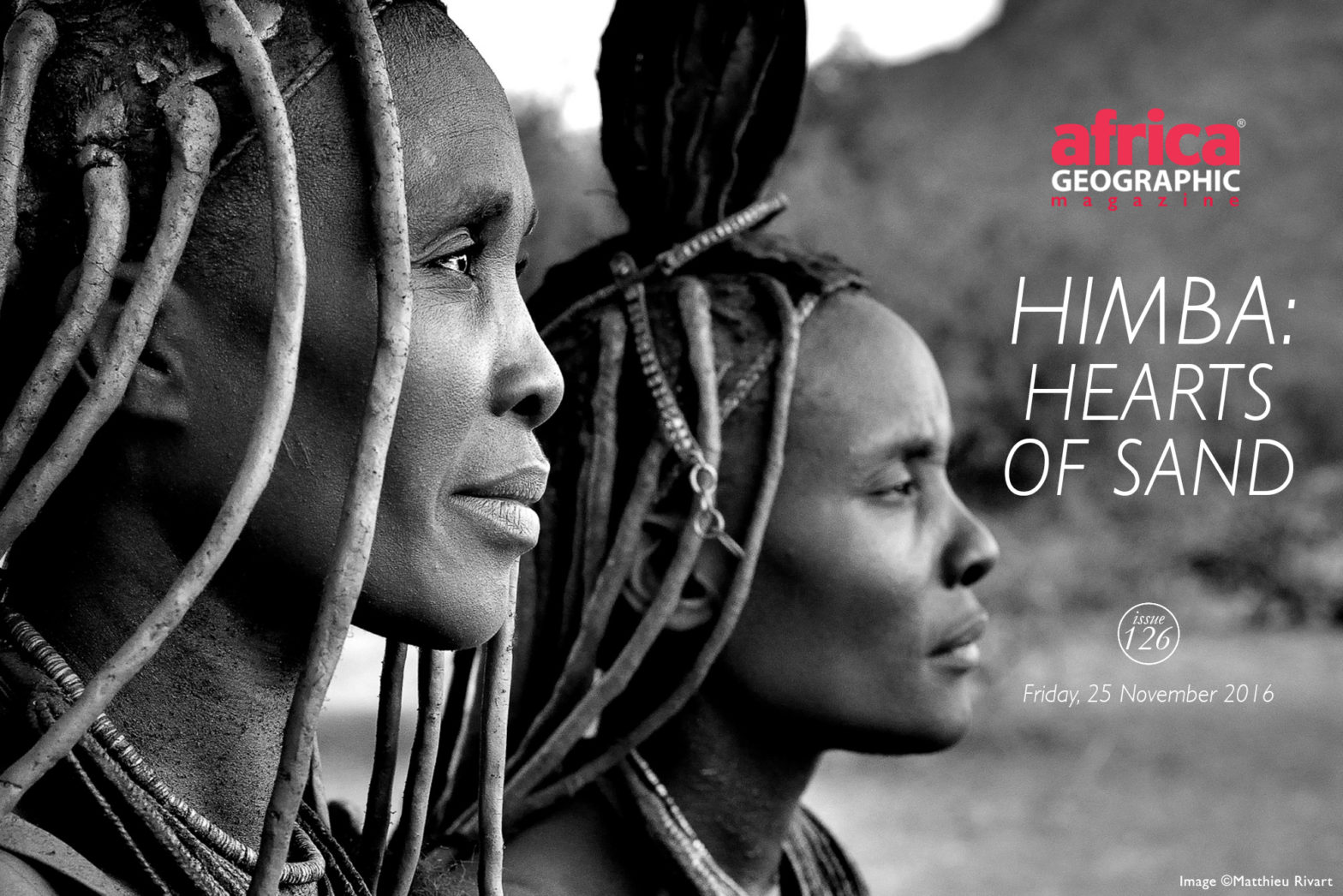

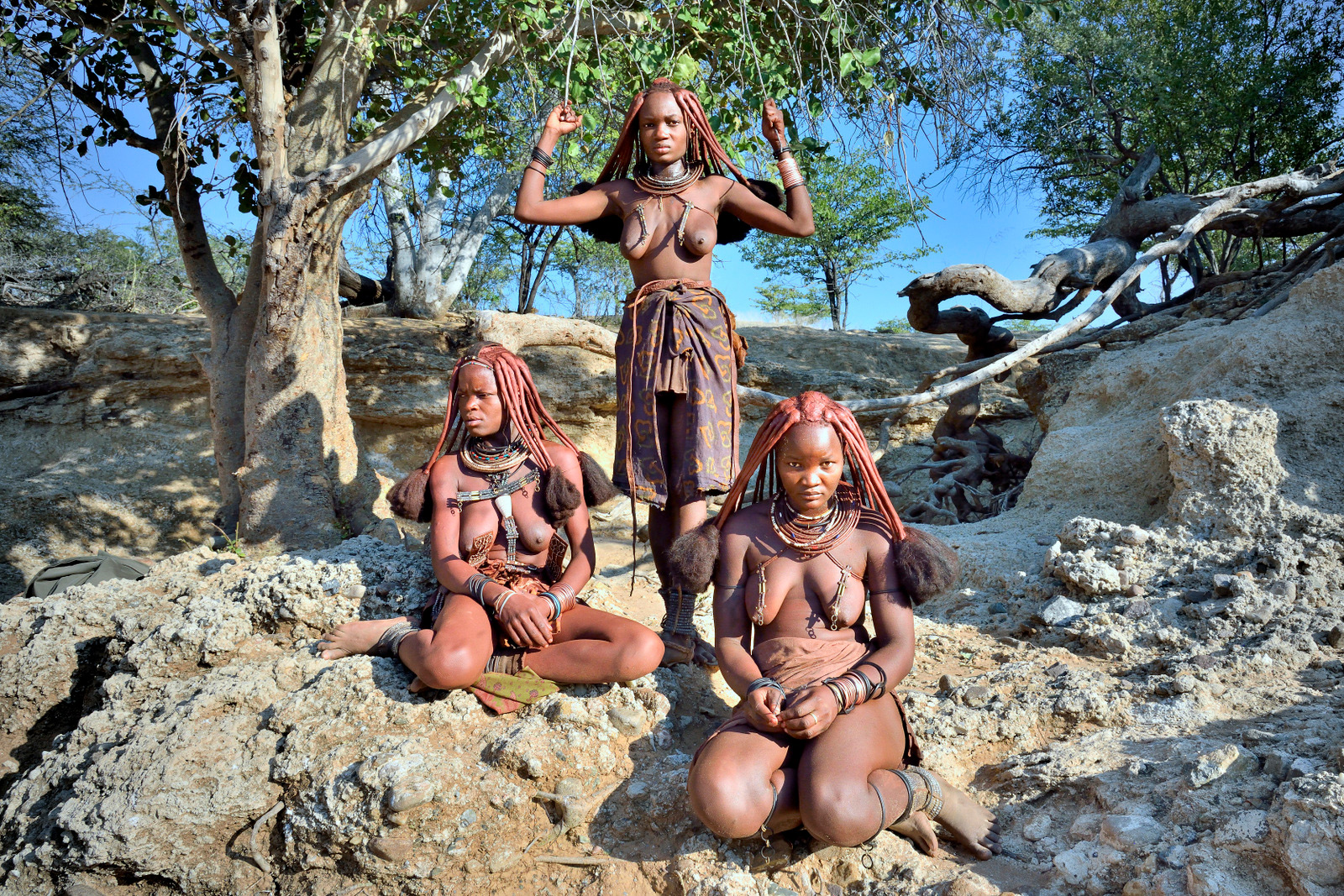

One of the most isolated and sparsely populated regions in all of Southern Africa, Kaokoland, can be fittingly described as one of Southern Africa’s true Edens and last remaining wildernesses. This arid landscape may come across as a harsh environment for living things, but it is, in fact, a refuge for two of the most famous and best-adapted desert icons in Africa – the desert elephant and the Himba people.

Descendants of the ancient Herero people, the Himba are a celebrated indigenous people with a population of about 5,000 – numbering one person to every two square kilometres in population density. They are renowned for the startling intricacy of their garments, as well as their traditional hairstyles. A characteristic feature of the Himba of this region is the red complexion of their skin, obtained by applying ochre as natural suntan lotion.

A semi-nomadic people, they are both proud and generous in offering visitors a glimpse into their traditional way of life, and a visit to a Himba village can be an insightful experience if undertaken with the due respect. It is crucial on any cultural tour in Africa to be sensitive of your tourist footprint; to always ask for permission when taking images, to pay your dues to the local chieftain and photographic subjects, and to be ever mindful of your conduct.

If you are lucky, you may also see the rare desert elephants while you’re in Kaokoland. Their true majesty reigns in an environment where they have mastered the principle of adaptation and sustainable resource use.

In true Namibia style, Kaokoland offers a landscape of magnificent, rugged contrasts. And as it’s not far from both Etosha and the Skeleton Coast national parks, it’s worth making this northern detour.

? White elephants fight in Etosha National Park ©Adriano Gannam

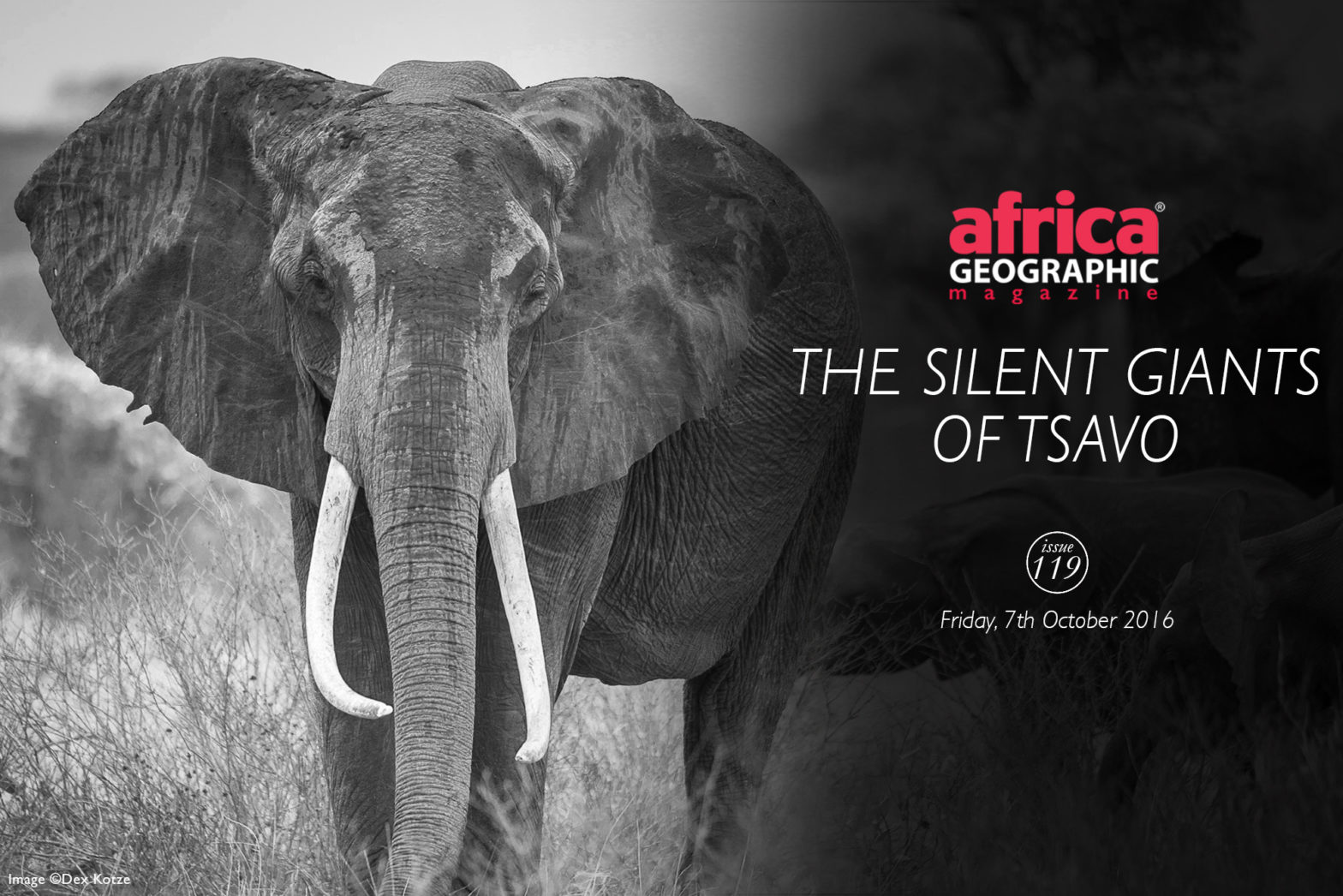

The gateway park to the north of Namibia and the Ovamboaland region, Etosha National Park holds its rightful place as one of the finest wildlife sanctuaries in the world. It is home to the Etosha pan, a salt pan which covers roughly a quarter of the park’s area and can be seen from space.

Far more than just a barren Namibian landscape, the ecosystem here is teeming with life. When the perennial rains grace the land, the pan becomes home to a population of roughly a million flamingos. And where water springs from the cracks of the earth around the edges of the pan, wildlife abounds in a diverse and thriving ecosystem.

The waterholes at the convergence of the pan and the bush are the main game viewing attraction, and with just a hint of patience, you can be rewarded with spectacular sightings of plentiful game. White elephants are one of the park’s main icons, but large prides of lions, stately giraffes and vast herds of springboks, Burchell’s zebras, oryx and wildebeests are ubiquitous too.

Any itinerary to Namibia would be incomplete without a few days at this ambassadorial national park, where natural history, wildlife and San culture all have a home.

? San bushmen hunting in //nhoq’ma ©Ana Zinger

The village of //nhoq’ma (Nhoma) lies about 40km from Tsumkwe in the north-east of Namibia, close to the border to Botswana. It is the ancestral home of a small population of Ju/’hoan San.

Various rock art sites prove that the San were the indigenous hunter-gatherers of Southern Africa, but now only approximately 55,000 members of this tribe remain in total – 20,000 of whom live in marginal settlements across Namibia.

Traditionally the San were nomadic, following food and water sources rather than farming or keeping livestock, and the women gathered edible plants, while the men hunted. There is evidence that until quite recently, many of their cultural practices were still being followed, but nowadays their traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle is often not feasible.

The community of Nhoma consists of about 50 adults and 100 children, who make their income from tourism. Time spent at Nhoma with this San community is a most rewarding back-to-basics experience. Mornings in the bush are spent tracking, and perhaps even hunting for the pot. The art of tracking, stalking and using the different hunting paraphernalia is eagerly demonstrated during this excursion. Lighting a fire with sticks, making rope from plant fibres and setting up traps make for a fascinating start to the day. Fruit, root, bark and tuber gathering is on the agenda for the ladies, and it is mesmerising to watch how much knowledge has been passed from one generation to the next. Soon you start to understand how hard survival in this environment is, even though the San’s resourcefulness makes it look so easy.

Social and jovial, there is no opportunity missed to engage in song, dance, play or games, and back at camp you can be guaranteed to witness many dances and rituals, and before you know it be drawn to partake in the laughter, encouragement and praise of these humble people of the sands.

? A nightscape in Tsumkwe ©Christian Boix

Tsumkwe is a town in the semi-arid region of Otjozondjupa, which is nearby the San village of //nhoq’ma. So if you have been visiting the bushmen, this is a lovely place from which to admire the night sky before crossing over to Botswana. The area is sparsely populated, and the nearest town that has more than 50,000 inhabitants takes about 10 hours to reach by local transport.

The land around Tsumkwe is not cultivated, which means that most of the natural vegetation is still intact, and the soil in the area is high in arenosols, which give the ground a sandy texture that makes it comfortable for camping. September tends to be the month with the most sunshine, but the most fun arguably comes when the sun goes down and when, thanks to there being no light pollution, it is magnificent to watch the Milky Way come to life in the clear night sky.

? Africa Geographic’s Travel Director, Christian Boix, in action ©Oz Pfenninger

Christian left his birth country of Spain – its great food, siestas and fiestas – to become an ornithologist at the University of Cape Town and to start Tropical Birding, a company specialising in bird-watching tours worldwide.

For 11 years following his arrival in Africa, he travelled to over 60 countries in search of over 5,000 bird species. Time passed, his children became convinced that he was some kind of pilot and his wife acquired a budgie for company. And that’s when the penny dropped that he needed to stay put a wee bit more.

In 2012 he took the reigns at Africa Geographic Travel as its Director and infused his energy and passion for all things African into the role. Contagiously enthusiastic, he is always eager to report back on his exciting travels across the continent, and never tires of sharing the joy of birding and exploration through his photography and guiding.

Click here for more information and stories about Namibia

For camps & lodges at the best prices and our famous ready-made safari packages, log into our app. If you do not yet have our app see the instructions below this story.

Anton

Anton

Born and raised in Sydney, Australia, Sarah Kingdom moved to Africa at the age of 21 and is now a mountain guide, traveller, and mother of two. When she is not climbing, she also owns and operates a 3,000-hectare cattle ranch in central Zambia.

Born and raised in Sydney, Australia, Sarah Kingdom moved to Africa at the age of 21 and is now a mountain guide, traveller, and mother of two. When she is not climbing, she also owns and operates a 3,000-hectare cattle ranch in central Zambia.

JANINE AVERY is the first to confess that she has been bitten by the travel bug… badly. She is a lover of all things travel, from basic tenting with creepy crawlies to lazing in luxury lodges – she will give it all a go.

JANINE AVERY is the first to confess that she has been bitten by the travel bug… badly. She is a lover of all things travel, from basic tenting with creepy crawlies to lazing in luxury lodges – she will give it all a go.

Raised in France, but now living in South Africa,

Raised in France, but now living in South Africa,

Aleksandra Ørbeck-Nilssen is a 26-year-old viking from Norway. She is the founder and CEO of

Aleksandra Ørbeck-Nilssen is a 26-year-old viking from Norway. She is the founder and CEO of

MEI CAPES-WINCH is half-Chinese, born in England, and South African at heart. She received a BA Joint Honours in French and German from the University of Warwick before spending a decade bumbling around Europe, Asia, Australia and Central America, then settling in Cape Town.

MEI CAPES-WINCH is half-Chinese, born in England, and South African at heart. She received a BA Joint Honours in French and German from the University of Warwick before spending a decade bumbling around Europe, Asia, Australia and Central America, then settling in Cape Town.

Dex Kotze is a businessman who brings 30 years of business experience to conservation. With a deep passion for Africa’s wildlife and wildlife photography, he

Dex Kotze is a businessman who brings 30 years of business experience to conservation. With a deep passion for Africa’s wildlife and wildlife photography, he