The five striking and powerful cheetah males sit motionless, shoulder to shoulder, staring at grazing antelopes on a sun-drenched grassland in the Maasai Mara National Reserve. Suddenly, their attention is drawn to another cheetah, sitting at a distance in the shade of a bush. Driven by instinct, all five set out at speed to investigate the intruder, intent on discovering which cheetah has wandered into their territory and confident in their own size and strength. The female, seeing the huge males approaching, dashes for the slim protection offered by a nearby thicket, followed by her tiny cub. It is Nora with her 2-month old daughter, and she has suddenly found herself facing five male cheetahs: the largest known male coalition in the Maasai Mara.

An extraordinary coalition

This coalition of five male cheetahs has been named the Tano Bora coalition, meaning ‘The Magnificent Five’ in the local Maa language of the region. Each male has also been given a local name: Olpadan (‘Great Shooter’ in Maa), Olarishani (‘Judge’ in Maa), Leboo (‘The one who is always within a group’ in Maa), Winda (‘Hunter’ in Kiswahili), and Olonoyok (‘The one who puts efforts to achieve better results’ in Maa). Since they arrived in the Maasai Mara, the five have proved to be an extraordinary force to be reckoned with and turned people’s understanding of cheetah behaviour on its head. So how did such a coalition come to be?

A female cheetah typically leaves her cubs when they are around 20 months old, and siblings will stay together in a group for several months. Once they reach sexual maturity, female and male siblings separate. Cheetah males can either become solitary (if there was the only male in the litter) or form coalitions – lifelong unions, formed by the males-littermates, which in some cases, may accept unrelated males into the fold, or even temporary groups of unrelated individuals.

The group of five young males came into the Maasai Mara National Reserve from the adjacent Naboisho conservancy at the end of 2016. Based on what we observed at the time, we believe that the coalition is made up of three separate parts, as two of the males were initially larger, and the three others were smaller and, therefore, most likely slightly younger. We do know that one of the smallest males at the time – Olpadan – split from his sister in November 2016 before joining four other males in December 2016. (His sister, Siligi also gained notoriety in 2019, when she emerged with 7 cubs, the largest littler recorded in the Maasai Mara.) Within a few months, Olpadan grew and established himself as the dominant male of the coalition.

Life in a group provides several benefits to its members: males can hold a “better” territory with more access to favourable habitat and prey; they can take down larger prey; they care for each other by sharing responsibilities in terms of vigilance and territorial patrols, and numbers provide better defence against rival males and kleptoparasites. The Tano Bora males are no exception to this rule and cooperate in everything, apart from breeding.

Breeding rights

The described encounter with the five males was not Nora’s first. Four of the males encountered her in December 2017, and Olarishani used his chance to mate with her while other members were off hunting. When the other three noticed the courting couple, they immediately rushed back and, not to be outdone, started mounting the pair. When in February 2019 the coalition again encountered Nora, she was with her single cub. Interestingly, although the males attacked Nora, they did not touch her cub, who fearlessly defended herself from approaching males by howling loudly, hissing, and growling at them. After investigating Nora’s reproductive status, all males lost interest and left her and the cub in peace. The same situation played out with another female – Rani. In March 2018, Olpadan mated with her, while two other males made attempts to mount. When the coalition next encountered Rani in June 2019, she was with a 4-month-old single cub. Again, the males were only interested in Rani and did not attack the cub. In August 2018, Olonyok mated with Nashipai, and 11 months later, all five males came across Nashipai with her two 2.5-months old cubs. Of all five males, Olonyok was the most persistent and interested in the female. He did not give up and returned to the female twice even after all the other males had left the spot.

The most likely explanation is that, along with the successful mating with one male, the attempts of the other coalition members to mount the female (but in fact mounting other males) helped to prevent an attack on the cub. Each of the males could have thought they had sired the cub. On the one hand, by mating with multiple males, females gain benefits including confusing paternity and thus avoiding infanticide, or else increasing the genetic diversity of offspring within a litter. On the other hand, competition among males for a female in oestrus reduces chances for all of the members of a male coalition to mate. Sometimes, only one dominates and gets the opportunity to mate successfully, which can be particularly problematic for unrelated males in a coalition. To mitigate this, the Tano Bora males implement useful tactics – one male separates from a group for a day or two, following and mating with a female and then re-joins his coalition-mates. Each member of the Tano Bora coalition has been observed mating with different females.

Who’s in charge?

Social animal groupings typically have a hierarchy with a linear or near-linear ranking and with expressed leadership of one of the members. In well-maintained cheetah coalitions, members share responsibilities, the level of affiliative behaviours between members is high, and aggression is low. However, in cases where the group consists of unrelated members, cheetah males face hierarchical instability. Olpadan became the leader of the coalition soon after he had joined the other four males. He would initiate hunts and lead the group across large distances, often walking for hours at a time. He was also the most successful hunter. By mid-2017, another big male – Olarishani – became co-leader, and both males began taking turns to decide when and which direction to move, where to cross rivers and how to approach a hunt. Interestingly, Olarishani also played the role of peacemaker during intragroup fights. The unfortunate Olonyok was often the target of Olpadan’s reverse aggression (aggression seen in a situation where, for example, groups of tourists disturb the cheetahs) and often these fights would escalate to involve all males. Under these circumstances, Olarishani would always step in to protect Olonyok.

In most cases, the dominance hierarchy is relatively stable, and members usually step aside when confronted by the leader. However, suppose the leader is weakened by injury, disease, or senility. In that case, the shift in ranking may occur, and the individual with the highest rank will move down to the lowest position. During intraspecific fights, cheetah males target anogenital area of rivals, and there have even been cases where males have bitten and cut off the testicles of intruders. That is what happened to Olpadan. His dominant status began to waver around the beginning of 2019, when two members of the coalition, Winda and Leboo, began to attack him regularly. In two cases, the fight happened during the courtship with different females. One fight in mid-March 2019 resulted in a serious injury to one of Olpadan’s testicles.

A fall from grace for Olpadan

After the necessary veterinary intervention and orchiectomy surgery, Olpadan lost his leadership position entirely, and Olarishani and Winda stepped forward to become the dominant members of the coalition. From being the most dominant, Olpadan became the lowest-ranking male in the group, the last in all joint activities from moving to feeding and was often the target of aggression when the coalition fed on smaller prey. Interestingly, Olonyok, whom Olpadan had targeted, became the one who tolerated Olpadan feeding next to him and who engaged with the ex-leader in mutual grooming after eating.

Cheetah social life is complex – unrelated males form alliances and maintain bonds for as long as it benefits all members of a group. Under certain circumstances, one of the members may start looking for an alternative group to join. In mid-February 2019, Olpadan tried to join another coalition, after the Tano Bora males chased two young males: Mkali and Mwanga, who had strayed into their territory. The ensuing pursuit saw the two intruders fleeing into a thicket, closely followed by the intimidating five. For some time, all seven disappeared deep inside bushes on the bank of a river, making sounds indicative of aggressive and defensive behaviours. After a few hours, four of the Tano Bora males departed, leaving Mkali, Mwanga and Olpadan. Instead of looking for his coalition-mates, Olpadan started following two males trying to sniff them and rest nearby, without making any attempt to harm them. When the two males responded with defensive behaviours, Olpadan would respond by displaying submissive behaviour – just sitting with his back to them.

By the next morning, Olpadan had abandoned his efforts and was desperately looking and calling for his own coalition-mates. When in the afternoon three males (Leboo, Winda and Olonyok) appeared in the area, Olpadan did not attempt to approach them, and over an hour later, they slowly approached the insecure Olpadan. While in the past, Olpadan had met returning males with aggression, this time, three males accepted him peacefully, and all set off to hunt together.

Cooperative Hunting and Cofeeding

Large groups of predators require more food, and each member must contribute to the hunt. It took five males over a year and a half to learn the necessary strategies for cooperative hunting. Initially, all members would chase different animals in a herd but, with time, developed an effective style of hunting where four would expose themselves to grazing antelopes, and the fifth would slowly stalk the prey. Group hunting by male coalition cheetahs has typically been associated with enhancing confidence among members. This we observed during the long rainy season of 2019-2020 when one male would confidently chase and tackle a bigger prey thrice its weight such as topi or even wildebeest (six times the weight of a cheetah!) Others will join the hunter when the prey is captured. Single cheetahs hardly ever hunt such big prey, unless they have recently lost coalition-mates.

When taking down large antelope, all five divide duties and act quickly and efficiently to feed as much as possible before the arrival of kleptoparasites. Cheetahs often lose their prey to larger predators – sometimes to lions and, more regularly, to hyenas. However, the Tano Bora males stand out in their relationship with other predators as well. On several occasions, they have chosen not to argue with a hyena but rather to share their kill with it instead! In both recent cases, cheetahs had made large kills (an adult topi and a wildebeest), and in both instances, Olpadan refused to feed alongside the hyena. In the first instance, all the other males were fed on the carcass from the opposite end to the hyena, while Olpadan watched from a distance. In the second instance, Olarishani and later Olonyok fed fearlessly next to a hyena while the three other males waited to the side.

A coalition like no other

The Tano Bora coalition is 4 years old, and it is developing through time – the relations between individuals (who are now around 5,5 years old) are undergoing dynamic changes that we never tire of watching. Nature is fraught with a variety of mysterious and amazing things, and in observing her creatures, patiently and with respect, she reveals her secrets.![]()

Read more about cheetahs here

About the authors

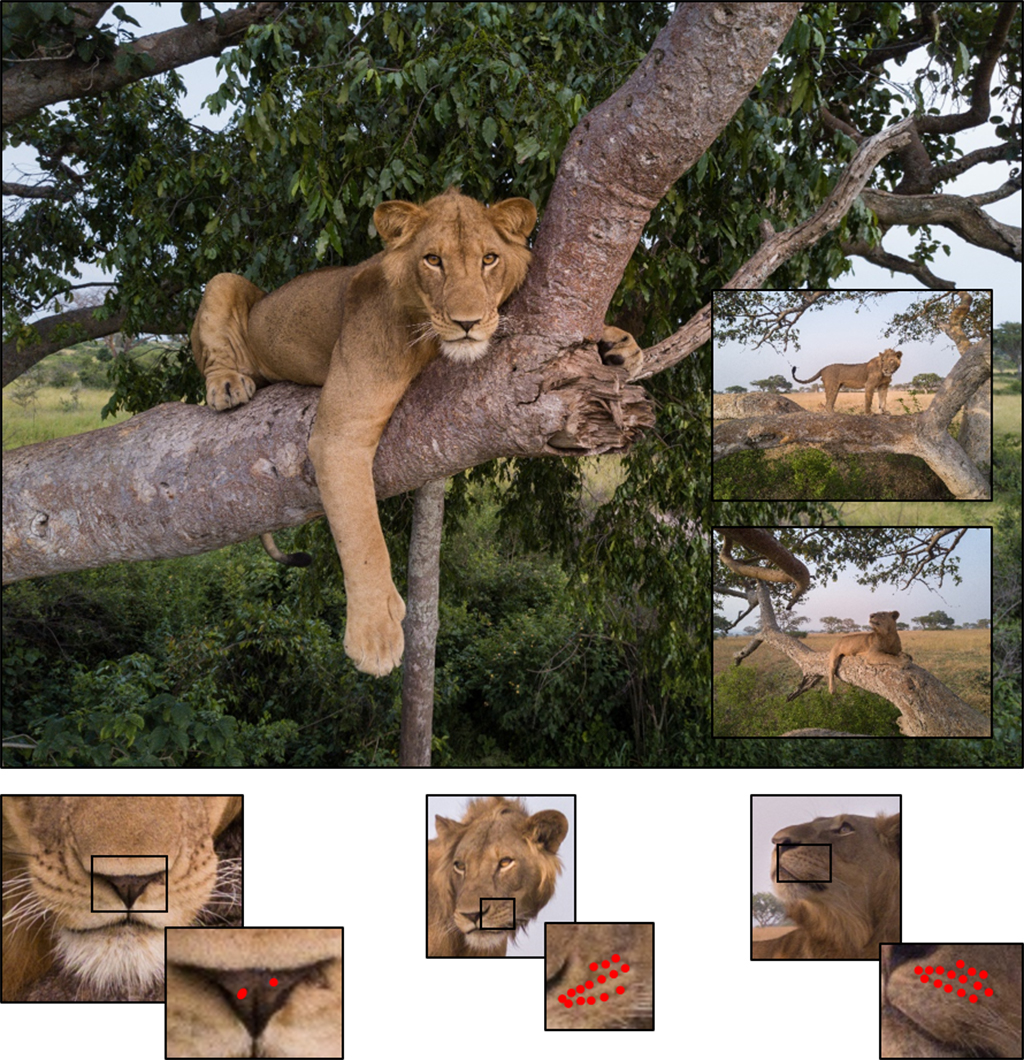

Dr Chelysheva is a renowned cheetah expert, with over 30 years experience of working with cheetahs in captivity and the wild. She is a PhD holder in cheetah ecology and behaviour and a member of the IUCN Conservation Planning Specialist Group. In 2001, Elena developed a cheetah identification method which helps to identify individuals from a month old. Using this method, she was able to determine kinship between individuals over the years and is now monitoring the fifth generation of some cheetahs. In 2011, Elena started cheetah research and conservation study in Kenya as a founder of the Mara-Meru Cheetah Project and here she shares her amazing discoveries.

Jeffrey Wu is a Canadian professional wildlife photographer based in Toronto, Canada. He is a judge of the Nikon Photo Contest and Nature’s Best Photography Africa and is also a Nikon China contracted photographer. He leads professional photo tours in Africa for ten months every year, mainly in the Masai Mara in Kenya. He is an expert on photographing cheetah hunting; he has photographed more than 300 cheetah hunting scenarios since 2013. His works have been published more than 50 magazines and newspapers internationally, including the Times, Outdoor Photography Canada, and Chinese National Geography.

A

A

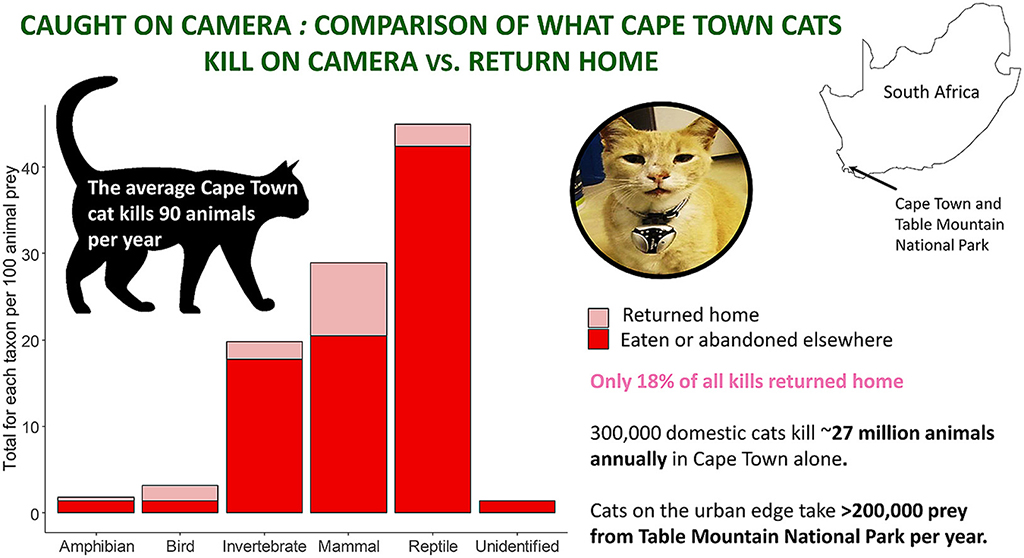

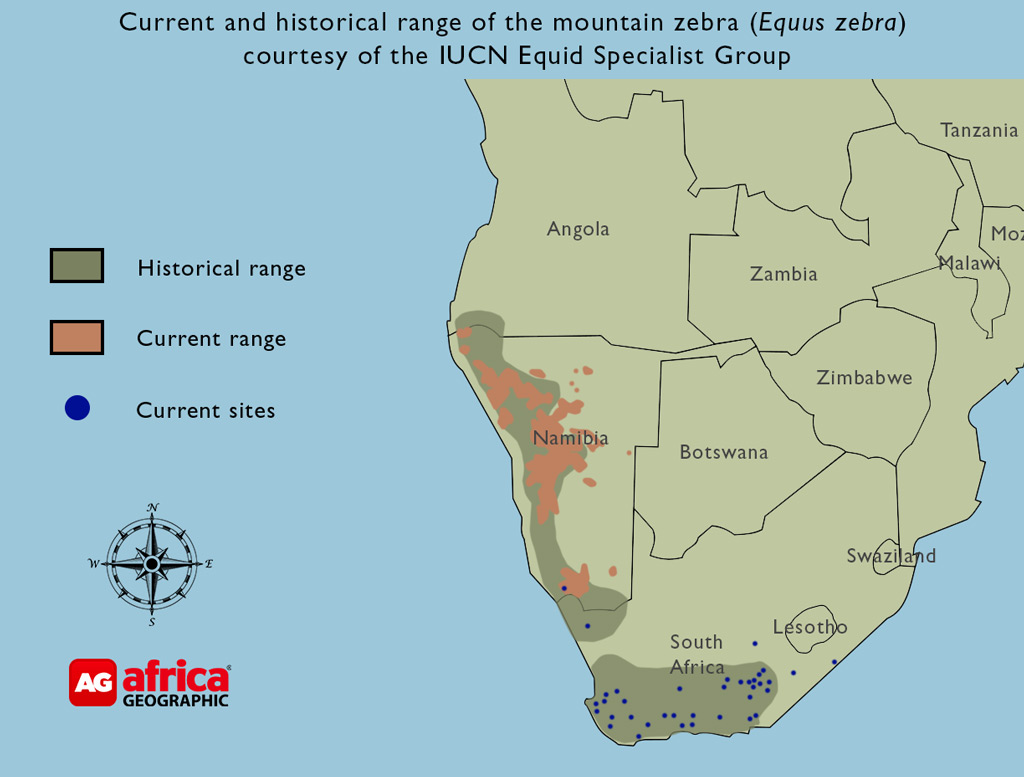

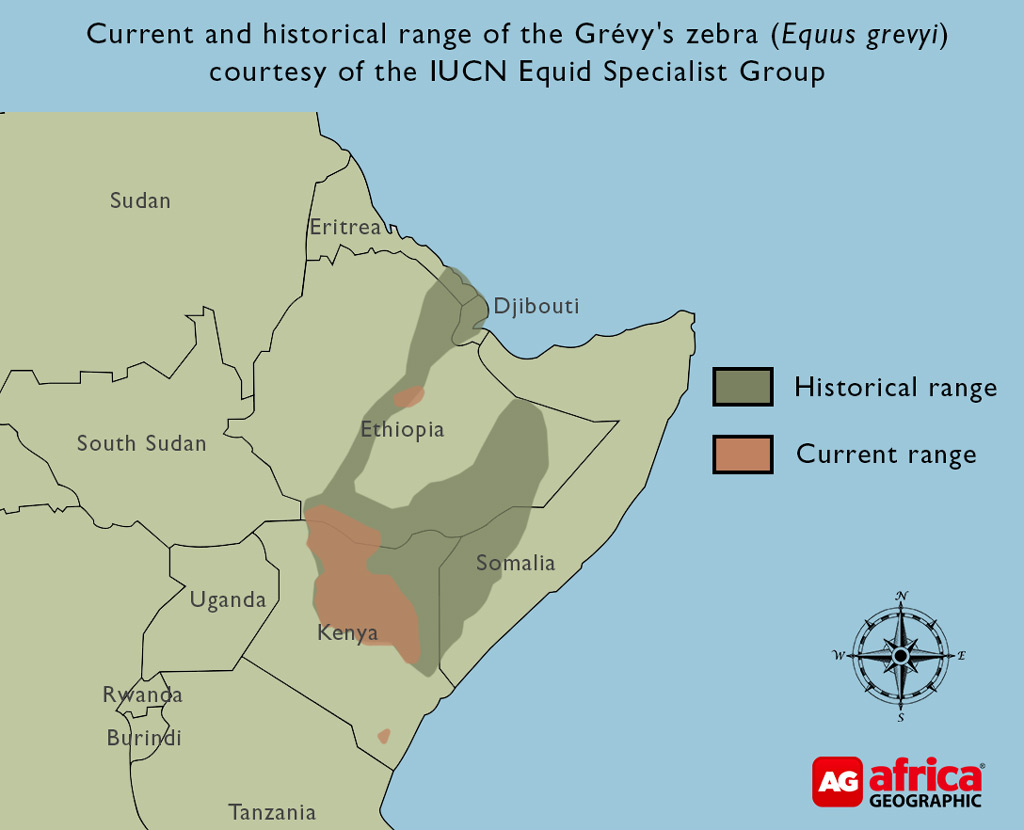

Freelance writer, Ron Swilling’s work is regularly featured in travel and outdoor magazines in South Africa and Namibia. Her work has also appeared in books Wild Horses in the Namib Desert: An equine biography, Road Tripping Namibia and the children’s story The World Famous Sunbeam Collector. Ron’s travels lead her off the beaten-track to discover diamonds in the dust, wild desert horses, unspoiled nature and freedom in never-ending landscapes. When at home in Scarborough, Cape Town, she delights in finding wonders in her very own back garden, like the Cape’s wild honeybees.

Freelance writer, Ron Swilling’s work is regularly featured in travel and outdoor magazines in South Africa and Namibia. Her work has also appeared in books Wild Horses in the Namib Desert: An equine biography, Road Tripping Namibia and the children’s story The World Famous Sunbeam Collector. Ron’s travels lead her off the beaten-track to discover diamonds in the dust, wild desert horses, unspoiled nature and freedom in never-ending landscapes. When at home in Scarborough, Cape Town, she delights in finding wonders in her very own back garden, like the Cape’s wild honeybees.

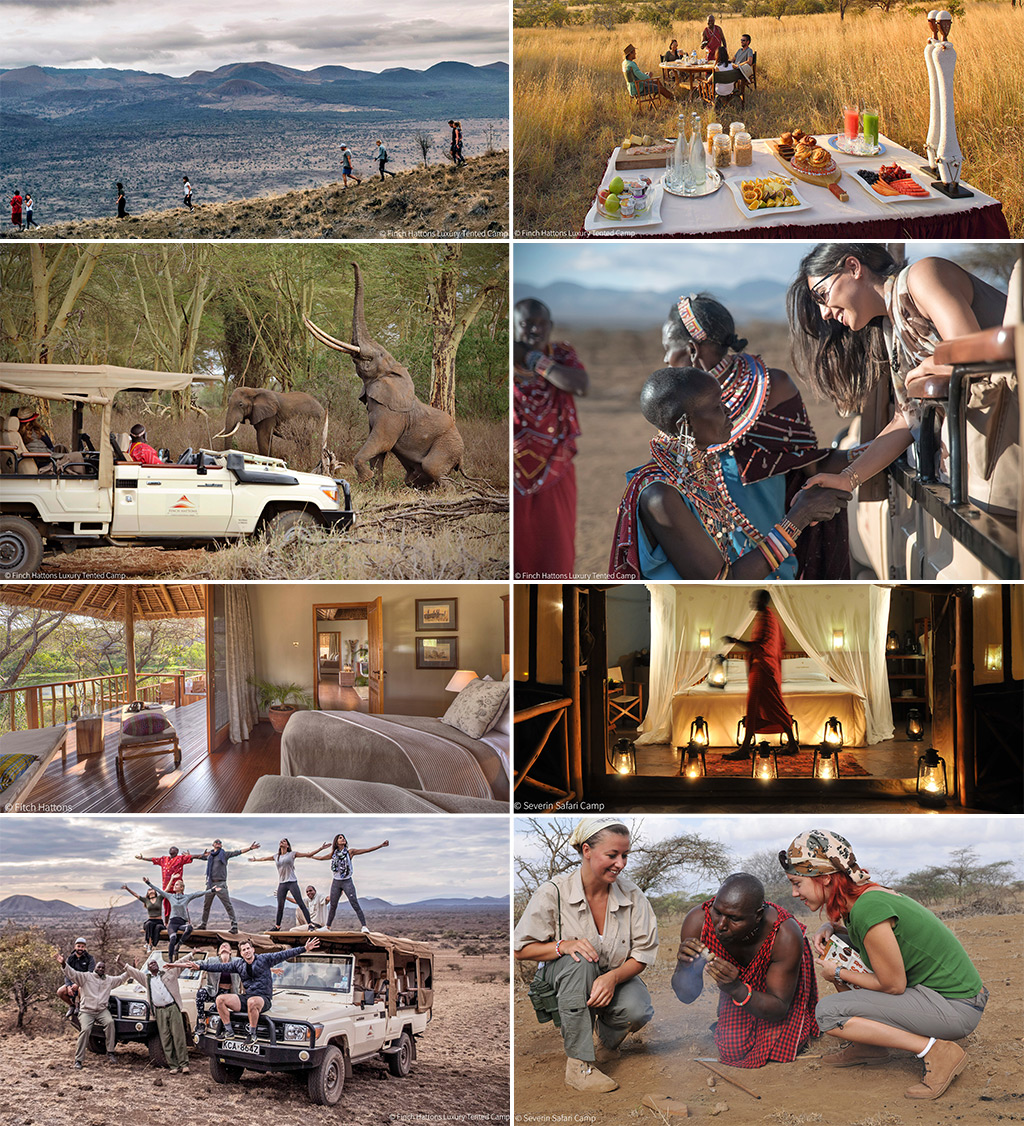

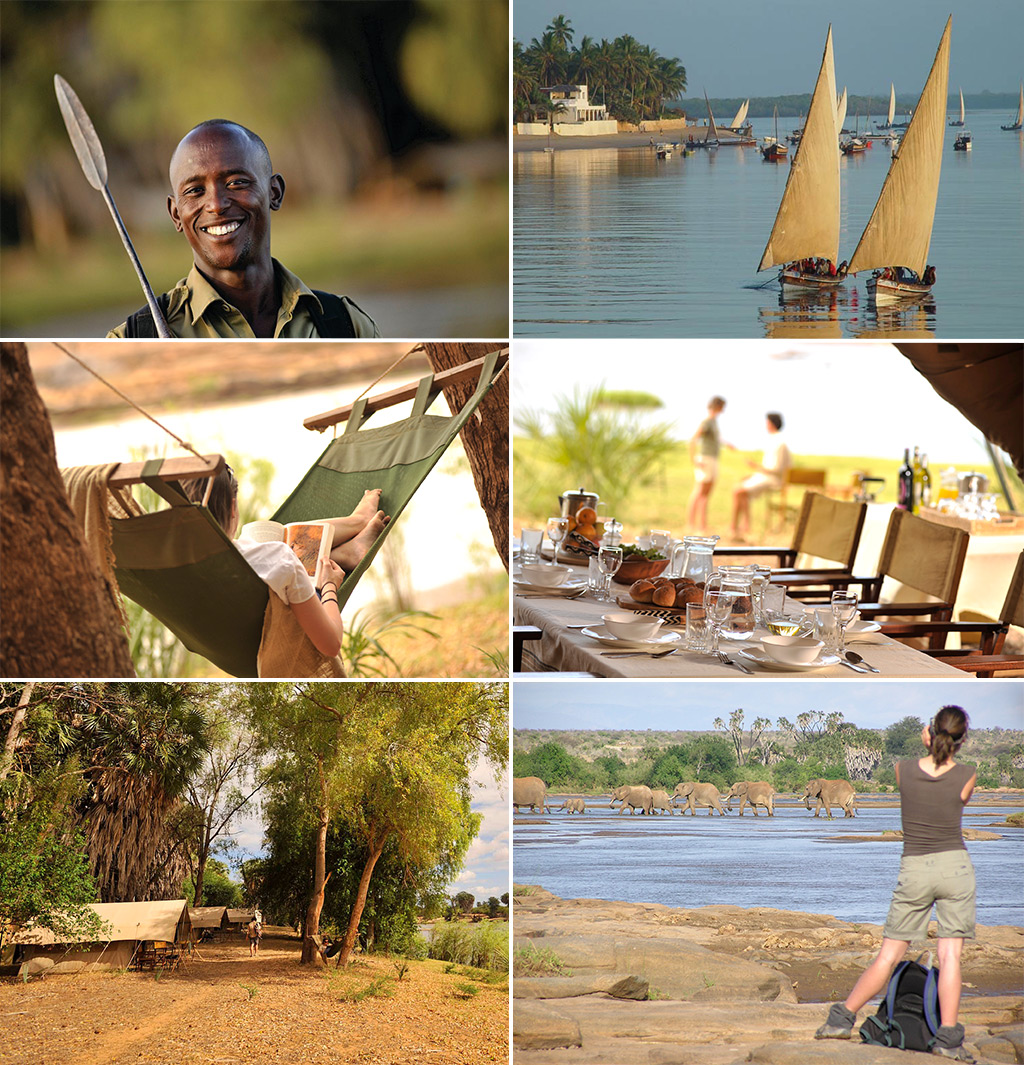

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

Jocelin Kagan’s passion for wildlife crystallised when she saw her first wild dog in 2010. ‘It was love at first sight’. Since then, Jocelin has been photographing and tracking wild dogs in Mana Pools in Zimbabwe, Botswana, the Timbavati in South Africa, and the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania. Jocelin has embarked on an ambitious undertaking to make known the plight of this most successful strategist of all predators. She holds Higher Primary Teacher’s Diploma with specialization in Speech & Drama from the University of Cape Town, a Master Practitioner Certification in Neuro-Linguistic Programming and a Henley Management College MBA, and is the published author of four books, an educator, and a public speaker.

Jocelin Kagan’s passion for wildlife crystallised when she saw her first wild dog in 2010. ‘It was love at first sight’. Since then, Jocelin has been photographing and tracking wild dogs in Mana Pools in Zimbabwe, Botswana, the Timbavati in South Africa, and the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania. Jocelin has embarked on an ambitious undertaking to make known the plight of this most successful strategist of all predators. She holds Higher Primary Teacher’s Diploma with specialization in Speech & Drama from the University of Cape Town, a Master Practitioner Certification in Neuro-Linguistic Programming and a Henley Management College MBA, and is the published author of four books, an educator, and a public speaker.