There exists a wilderness in the highlands of Kenya where love, labour and a little luck created a conservation model so successful that it has shaped the fortunes of the land and communities around it. Today, Lewa Wildlife Conservancy is a haven for the rare and wonderful wildlife of the region while simultaneously offering one of the most exclusive and individualised safari experiences in East Africa.

Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and surrounds

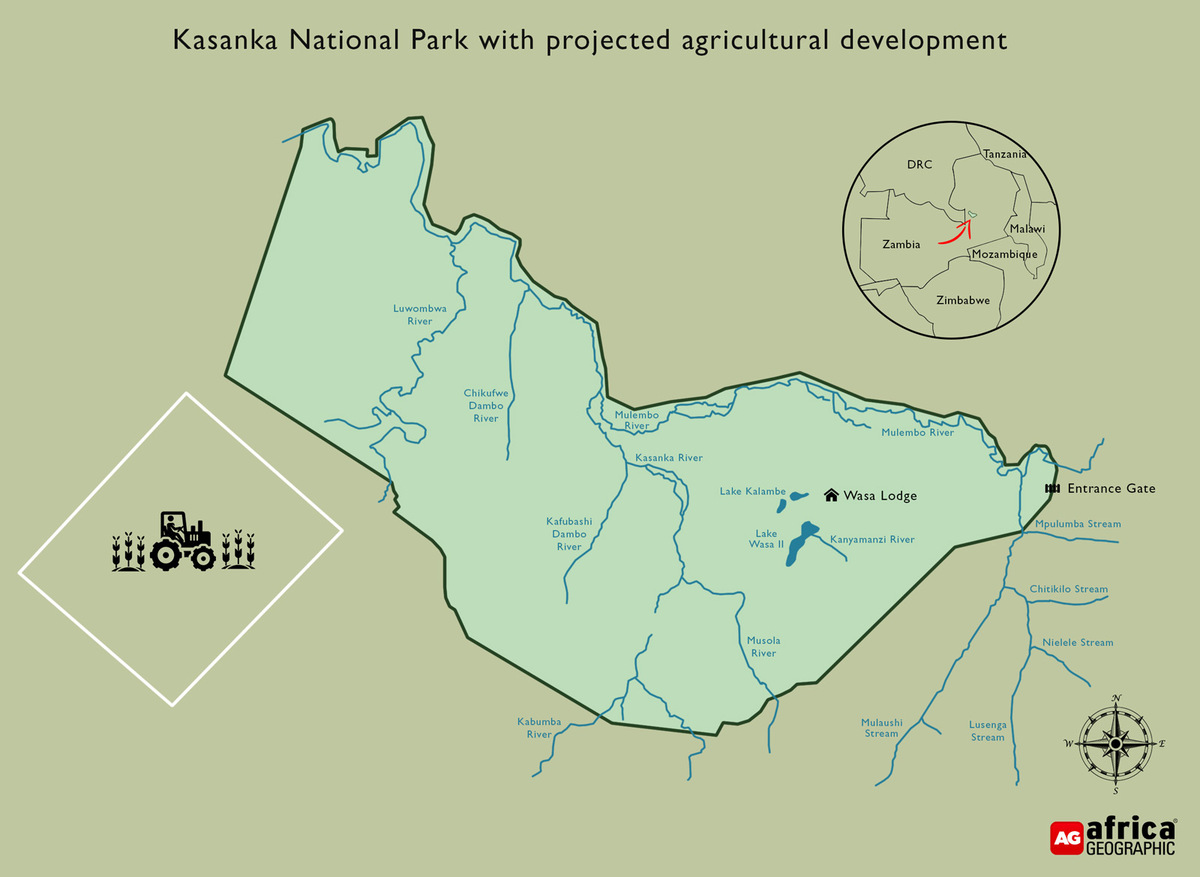

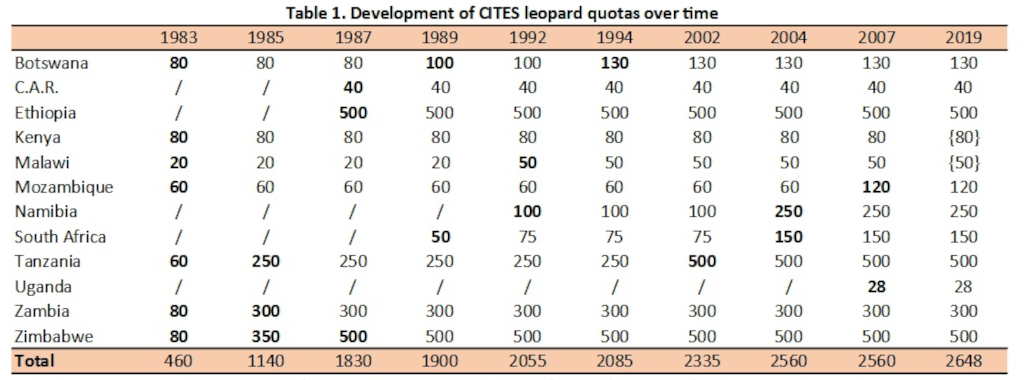

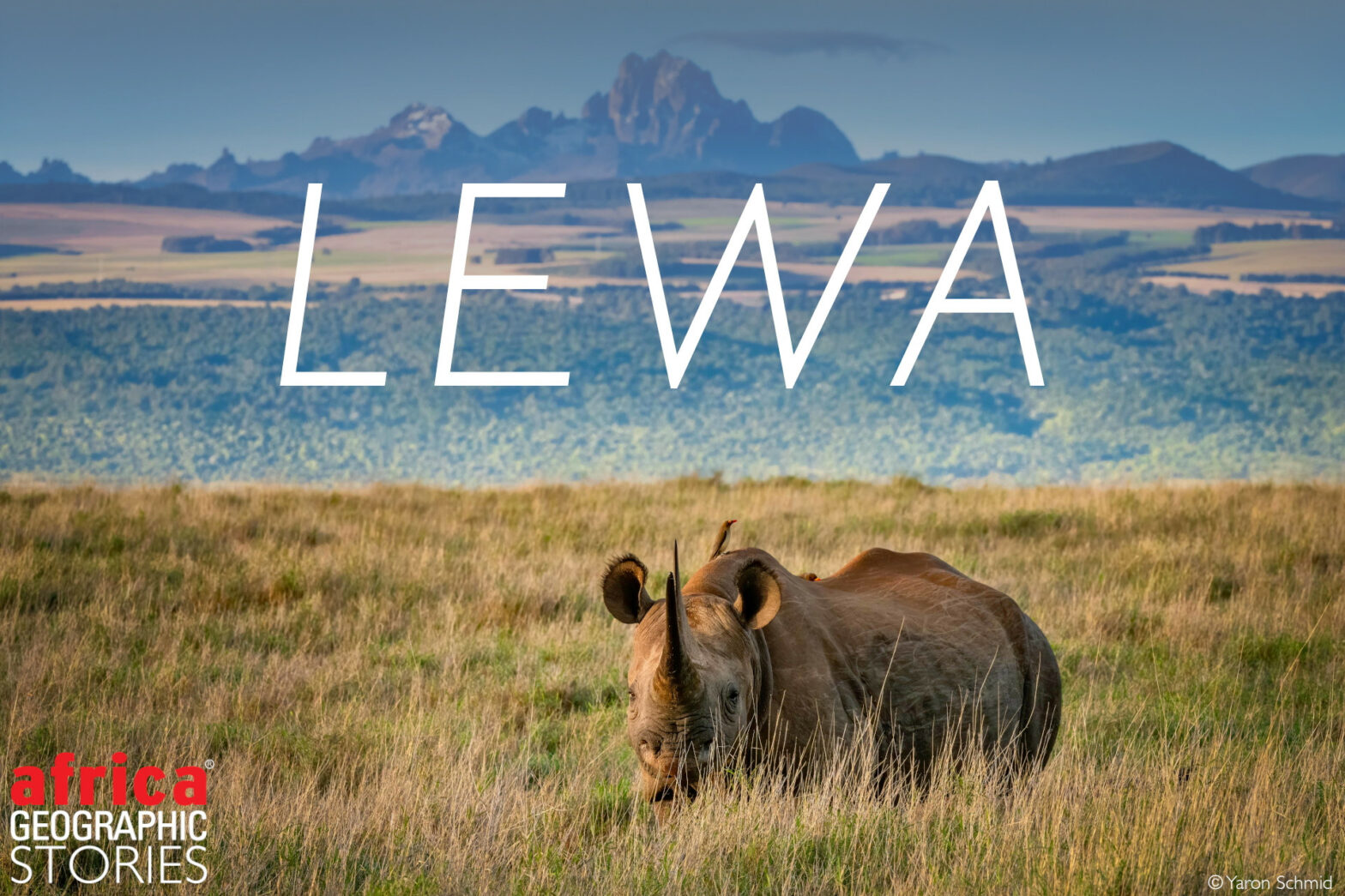

The Lewa Wildlife Conservancy covers 250km² (25,000 hectares) in the corner of Kenya’s Meru County, bordering Laikipia and Isilio counties to the west and north, respectively. Though technically situated in a separate county, Lewa is a part of the wider Laikipia landscape. Most of the conservancy lies on the Laikipia Plateau at altitudes of over 1,500 metres. Just 40 km to the south, the jagged figure of Mount Kenya looms on the horizon, its rolling foothills imparting a dramatic topography to Lewa.

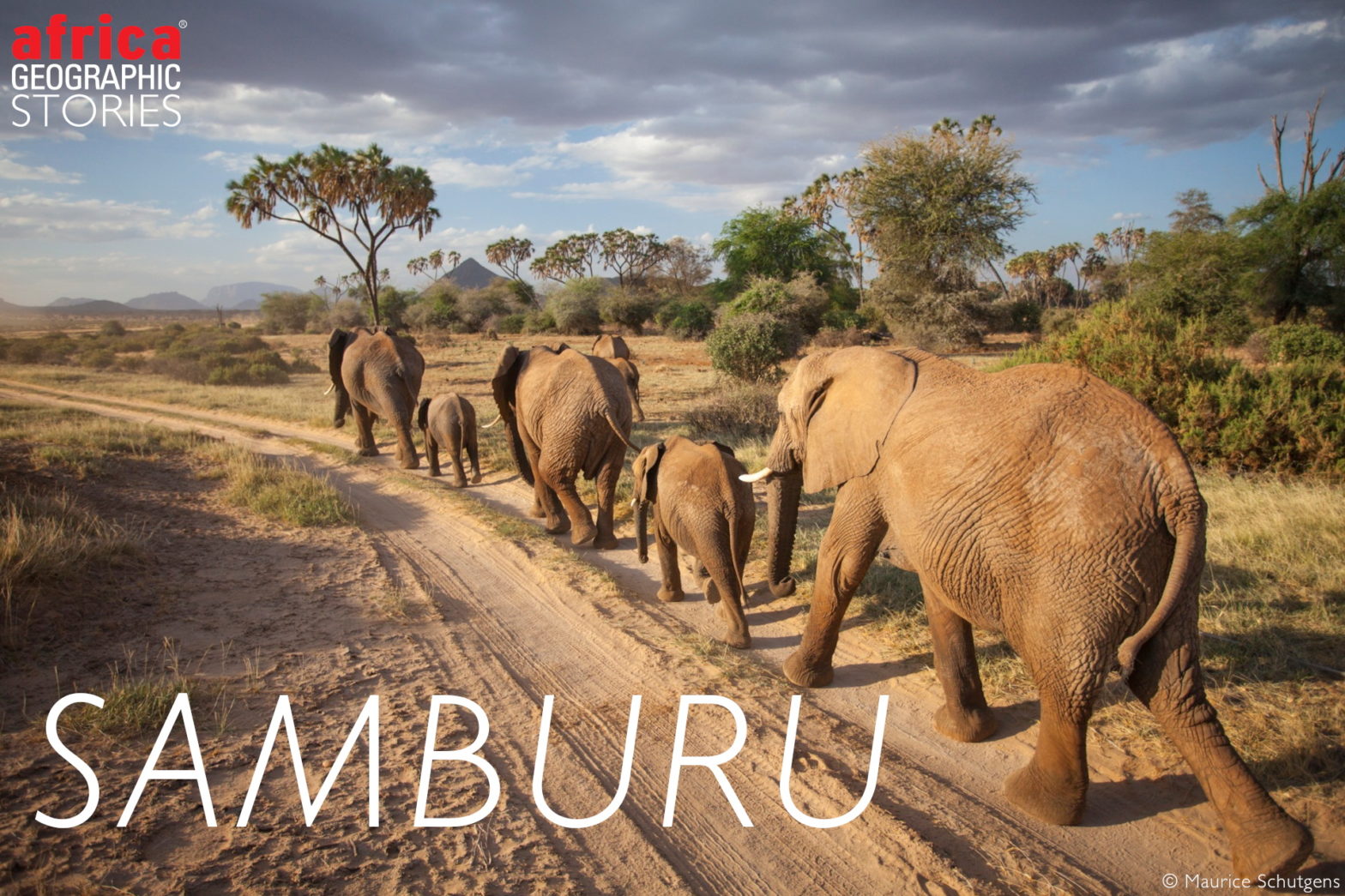

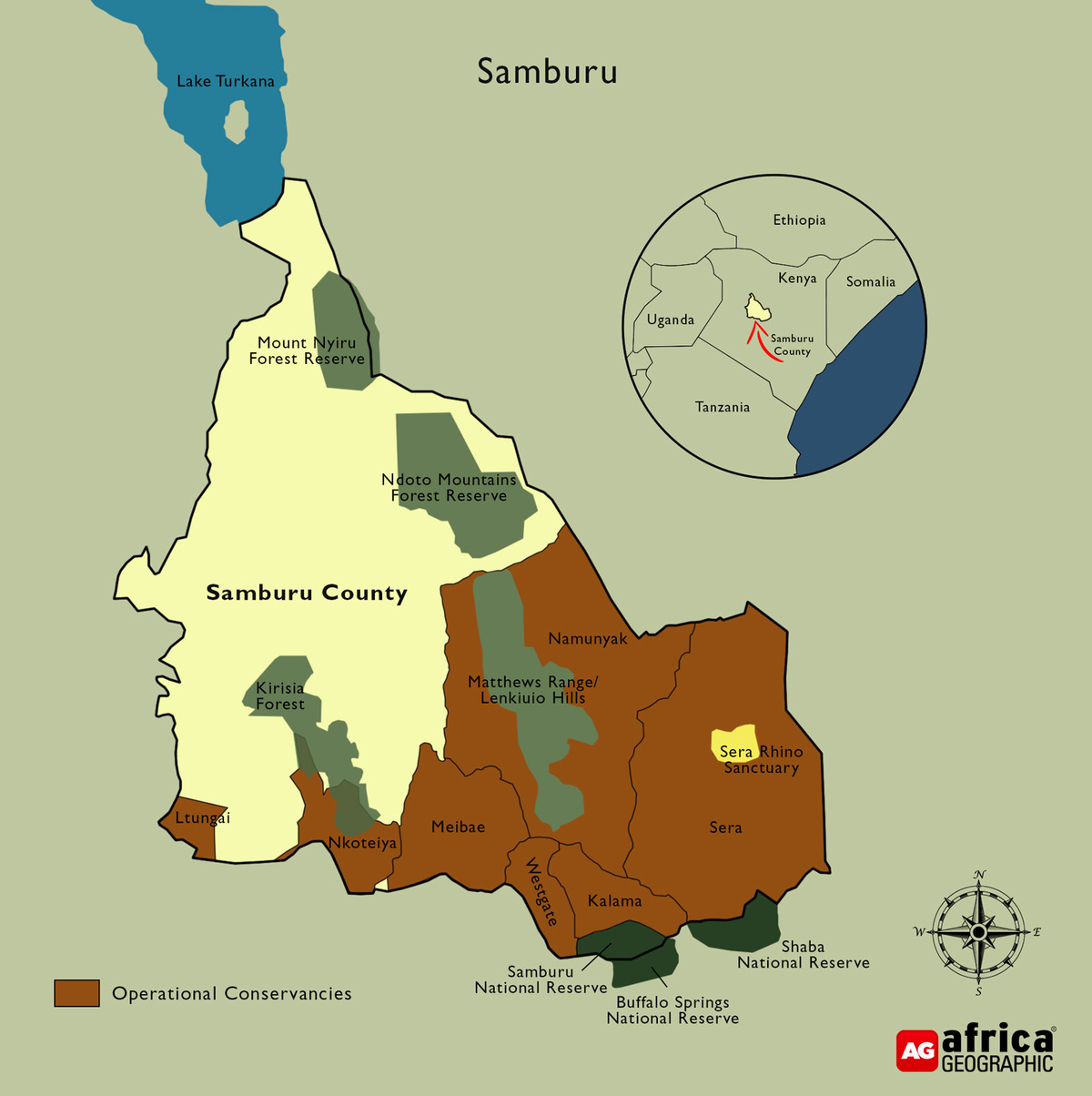

This spectacular visual contrast between the lush montane forests at the base of Kenya’s tallest mountain and the arid grasslands and sparse woodlands of Lewa is a significant ingredient in the conservancy’s wild magic. Another is, of course, the abundant wildlife. Unusual for this part of the world, Lewa is fenced but with tactical gaps left open based on animal movements. This allows the animals to move between the various surrounding ecosystems, including the vast Laikipia conservancy network and the Samburu ecosystem to the north. Lewa is also open to the neighbouring Borana Conservancy to the west.

Visitors to Lewa’s lodges are granted exclusive access to this wilderness playground. They are afforded opportunities that go far beyond the average game drive (though these are, of course, still an exciting aspect of any visit, given the wildlife on display). Despite the conservancy’s burgeoning success in conservation and tourism, the atmosphere remains down-to-earth – a perfect blend of homely warmth and world-class luxury guest experience.

The story

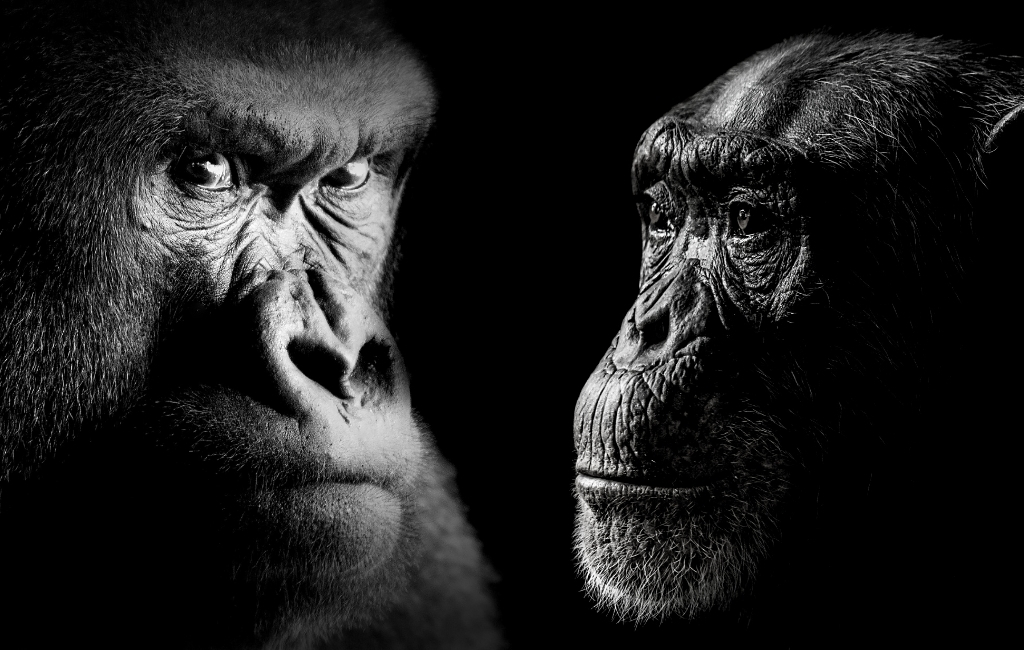

Lewa’s conservation journey is an integral part of the guest experience because it adds to the depth of understanding of the land, as well as her people and animals. The story is deeply rooted in Kenyan conservation history. It was once an operational cattle ranch owned by the Craig family who partnered with philanthropist Anna Merz to create a rhino sanctuary during the height of the poaching crisis in the early 1980s. Rhino numbers had been decimated, and their future was hanging very much in the balance. The remaining rhinos in northern Kenya were quickly gathered and sequestered safely away in the fenced and guarded Ngare Sergoi Rhino Sanctuary. As the numbers grew, the sanctuary was expanded to include the rest of the ranch. Thus Lewa started its journey to becoming one of Kenya’s premier safari destinations and conservation pioneers.

Cognisant that the future of any conservation mission depends on the fortunes of the surrounding communities, the Lewa approach has always been one of inclusivity and tangible contribution to rural livelihoods. With the support and encouragement of Lewa CEO Ian Craig, community-owned and managed conservancies began to spring up around Laikipia and Isilio. So successful was the multi-pronged approach to land management, security and tourism that Lewa Wildlife Conservancy was constantly called upon to support and guide the surrounding protected areas.

The result was the formation of the Northern Rangelands Trust (as a separate entity from Lewa), which now oversees over 30 different conservancies and community lands. Its mission: to develop resilient community conservancies to “transform people’s lives, secure peace and conserve natural resources” through providing funds, advice, training, and support.

A tribute to the success of Lewa’s conservation efforts came in 2013 when UNESCO declared both Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and neighbouring Ngare Ndare Forest Reserve an extension of the Mount Kenya World Heritage Site.

Ngare Ndare Forest Reserve

Just south of Lewa is the Ngare Ndare Forest Reserve, part of the Mount Kenya forest ecosystem. This fairytale forest is one of Kenya’s hidden gems – frequented mostly by locals and Lewa guests. Thick ferns line the lush forest trails, and the trees are draped in thick vines to the point that one might be forgiven for expecting to see a yodelling Tarzan swinging in the canopy overhead. Though the forest lacks any large primates (apart from the visitors), there are plenty of elephants and black-and-white colobus monkeys hidden in and among the trees!

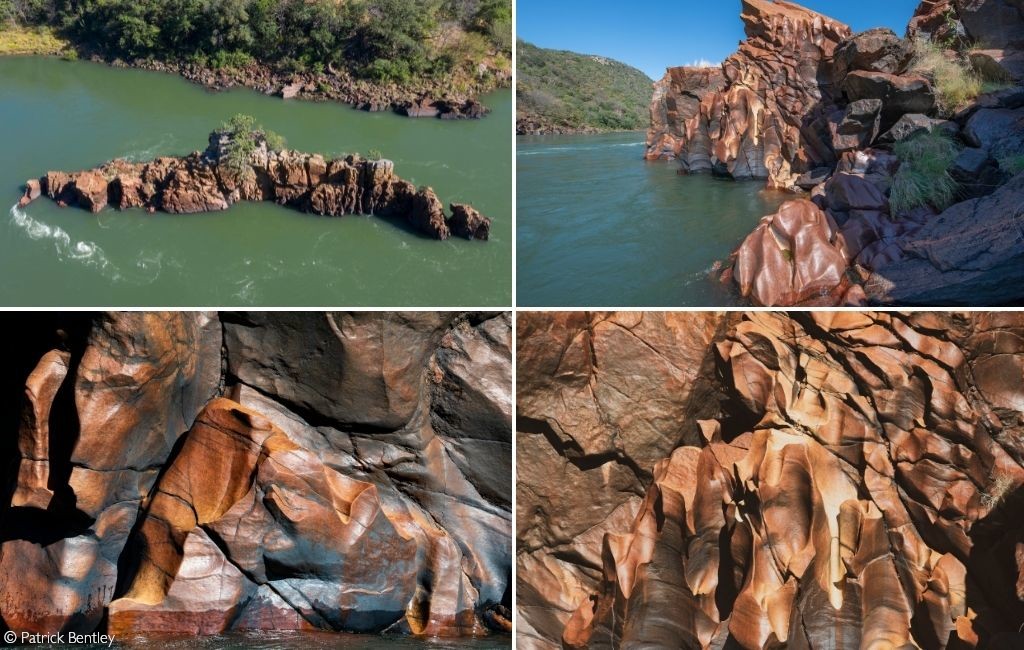

There are two main attractions in Ngare Ndare: the waterfall tumbling into an azure pool and the canopy walk. The first of these can be found in a spectacular rocky grotto, where swimming is permitted for those able to brave the cold of the mountain spring water. The canopy walk consists of a hanging walkway ten metres above the forest floor. This is the perfect place to take in the beauty of the forest, particularly at sunset when the trees are burnished in shades of gold and green.

The elephants went in two by two (Hurrah!)

One of the primary justifications for expanding the Mount Kenya World Heritage Site to include Lewa and Ngare Ndare was the 14km wildlife corridor linking the Mount Kenya National Park to Ngare Ndare. The narrow strip of fenced land runs between farmlands and has proved to be of immense value to the elephants of central and northern Kenya (as well as the surrounding farmers and their fields). From a conservation perspective, this elephant migration corridor is one of the greater Lewa landscape’s most fascinating features.

We know from recent research that elephants are now restricted to just 17% of their historical range, forced to navigate human-dominated landscapes and no longer able to follow traditional migration routes. The elephants of this ecosystem would have moved between the forests on the slopes of Mount Kenya (and, of course, the readily available streams fed by glacial runoff) and the more arid regions of the north (Samburu and the Matthews Range) depending on the seasons and rainfall. This migration corridor, created in 2010, allows the elephants to continue to do so, connecting the habitats while reducing conflict with the rural communities occupying the space between them. The underpass beneath the main highway was the first of its kind in East Africa and allows the safe passage of elephants and an assortment of other animals. Astonishingly, it took the first elephant just 12 hours to discover the completed underpass.

Wild Lewa

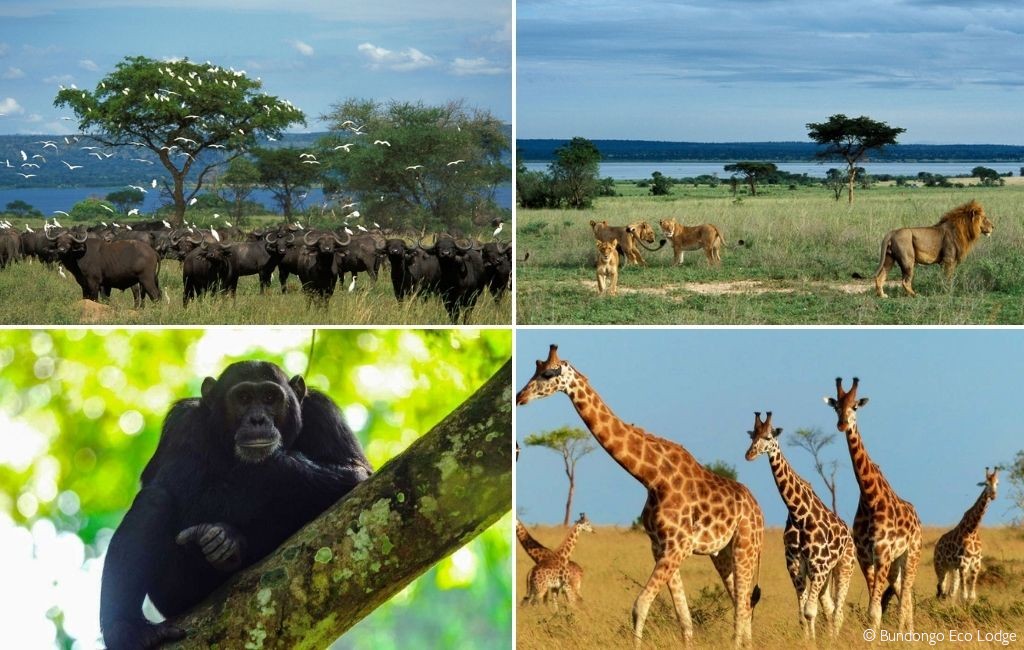

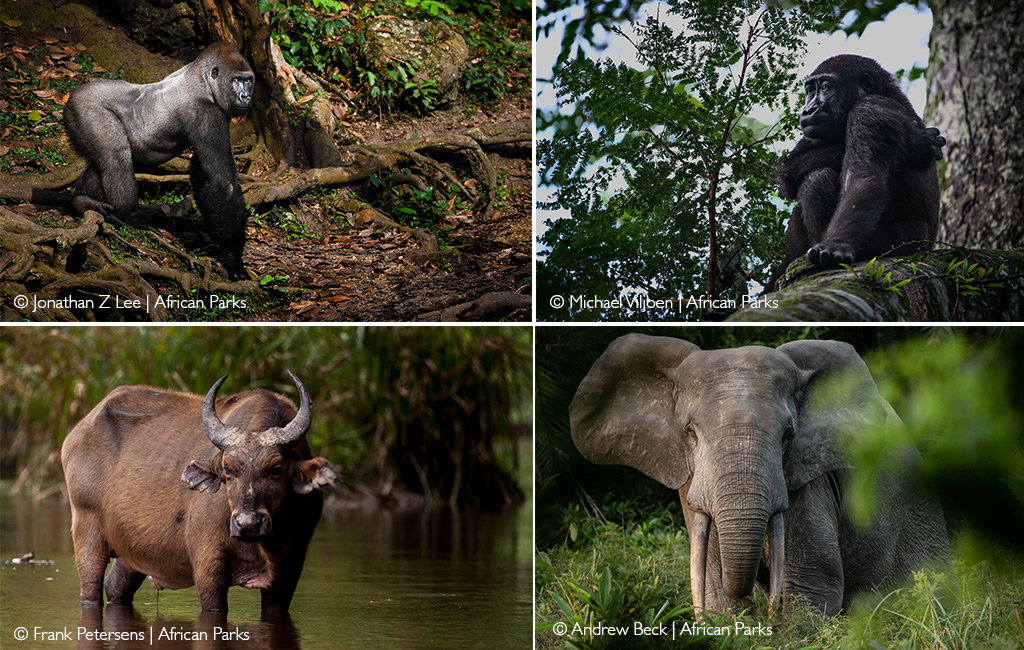

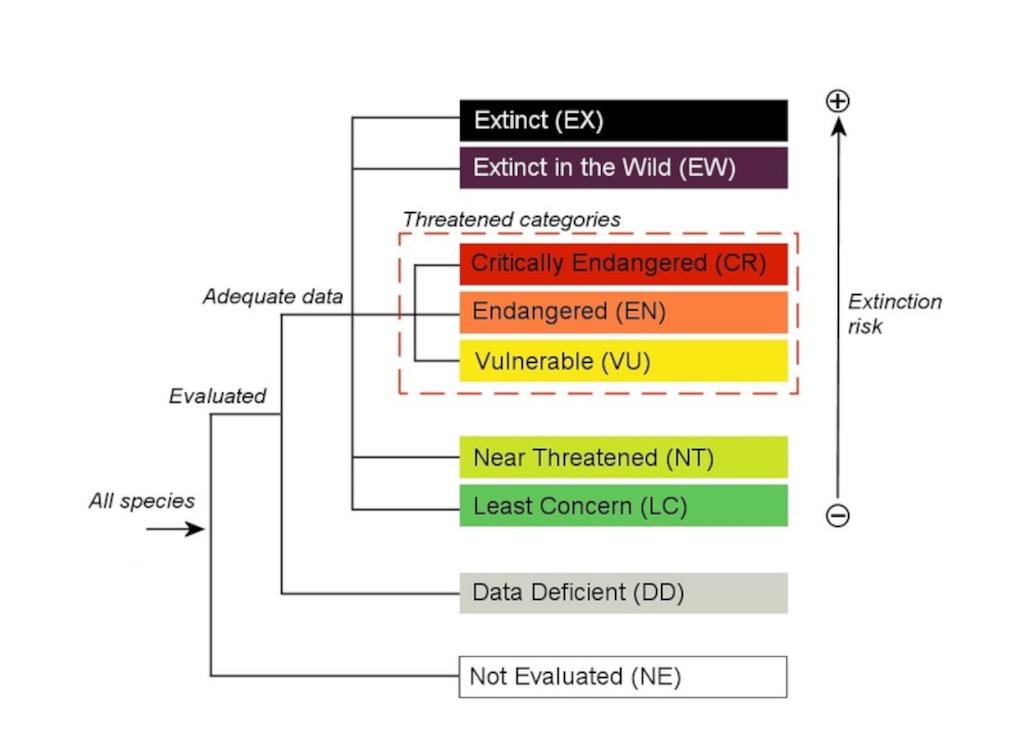

Lewa’s deep conservation roots have ensured a thriving wildlife population, including the Big 5 (though leopard sightings are still relatively unusual), rarities like the Grevy’s zebra. Naturally, both black and white rhinos are one of the main drawcards, and Lewa is one of the best places to view the two African rhino species. Not much compares to the sight of a critically endangered black rhino out in the open on Lewa’s grasslands, with the singular outline of Mount Kenya in the background.

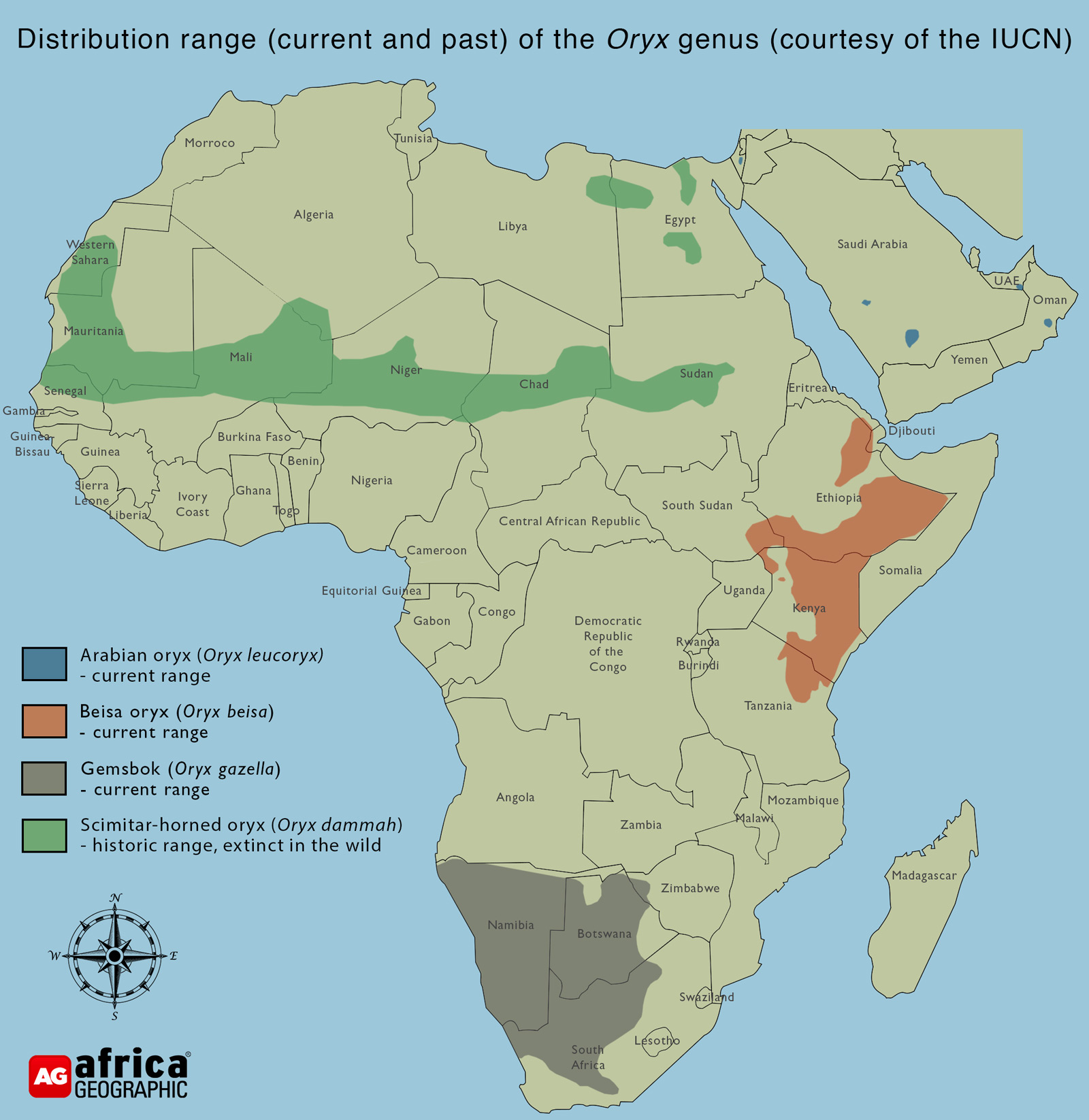

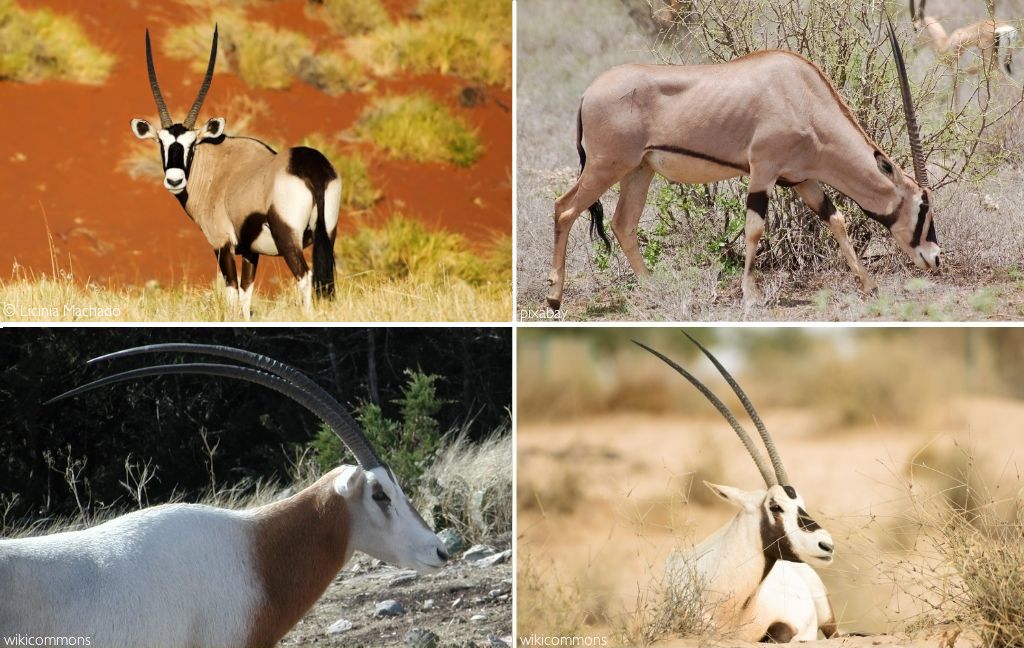

The northern “specials” are all present, including the reticulated giraffe, common beisa oryx, gerenuk and Somali ostrich. The conservancy is a population stronghold of the endangered Grevy’s zebra, and the growing numbers have been translocated to bolster populations in surrounding conservancies. Lions and cheetahs abound, and packs of African painted wolves occasionally make a fleeting appearance.

To protect and to conserve

Have you ever wondered about what goes on behind the scenes in keeping a reserve operational and safe? Lewa’s phenomenal guest experience offers a transparent insight into the day-to-day realities of reserve management and even allows guests to join its various conservation initiatives where appropriate. This includes everything from visits to the local community schools and clinics to anti-poaching demonstrations and a chance to meet the tracker dogs. Rather than presenting a sanitised safari disconnected from reality, the Lewa approach is one of absolute authenticity.

Explore & Stay

This freedom of experience is a trademark of the central and north Kenyan tourism mantra, and the wealth of activities on offer makes the Lewa safari unlike any other. Game drives form the backbone of sedate exploration, but guests can opt to join the guides tracking the wildlife on foot or even rock their way across the landscape on the back of a camel. The conservancy is home to several exceptionally well-trained horses and offers rides for both beginners and more advanced riders. The joy of viewing wildlife from horseback is that the wild animals respond differently to the horses than they might to people on foot. The result is a safe and close encounter with wildlife that does not affect natural behaviour. Guests wanting an even more immersive experience can request a night out under the stars, and the lodges will set up a fly camp. From bush breakfasts to sundowners, nothing is ever too much trouble in Lewa…

This region of Kenya experiences two rainy seasons, which fall over April/May and November. At the height of the rains, the treacherous black cotton soils make navigation almost impossible and the lodges close operations in April and November. The dry season between June and September offers the best wildlife sightings. This does fall over the high tourist season, and the lodges are busier than normal. However, it is worth bearing in mind that this is by conservancy standards, and the experience remains exclusive.

There are several different lodges scattered throughout the conservancy, ranging from high-end to ultra-luxurious. Those wishing for more budget options can stay in the Mount Kenya National Park or the neighbouring Il Ngwesi Community Conservancy. However, as previously mentioned, only guests staying in Lewa will be granted access to the conservancy.

Want to go on safari to Lewa Wildlife Conservancy? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

A recipe for success

Protecting Africa’s remaining wild spaces in today’s world is no easy task and requires juggling security, conservation, community relationships and local livelihoods in a competitive tourism environment. There is no such thing as a perfect recipe for securing the future of Africa’s protected landscapes but the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy stands out as one of Kenya’s most illustrious success stories.

Resources

For more on the Laikipia plateau see here

For more on Samburu see here

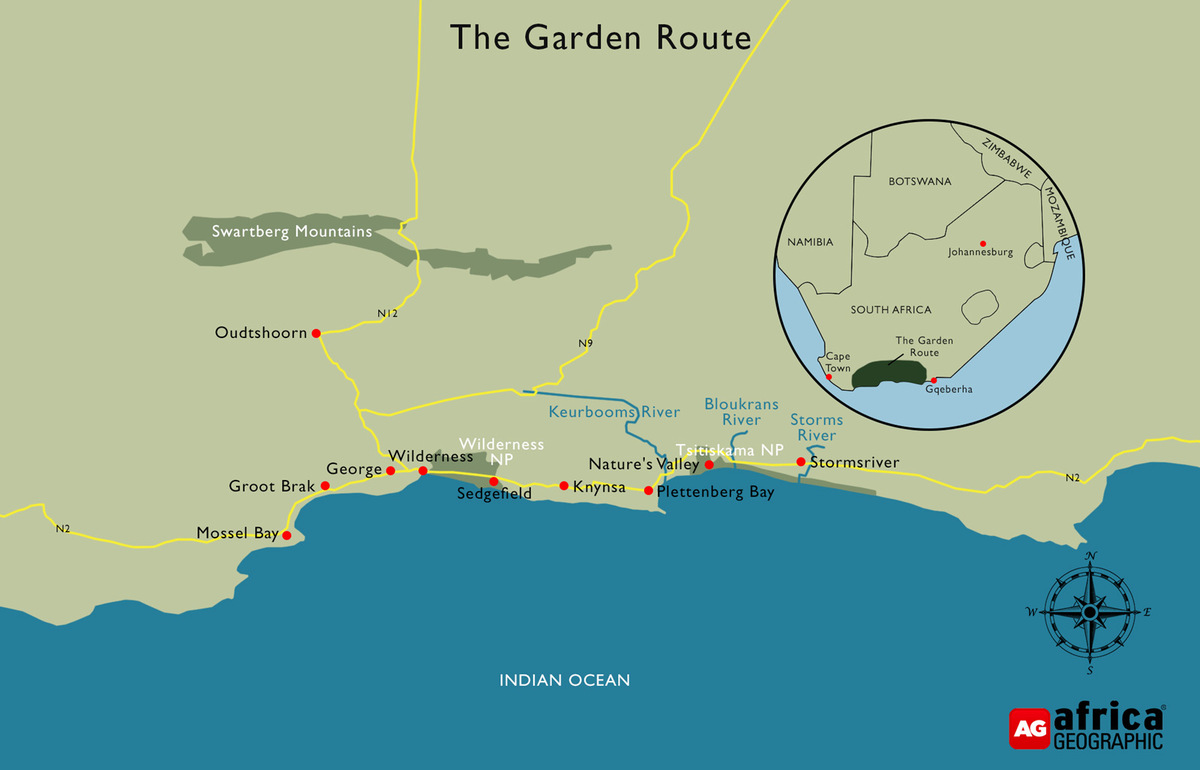

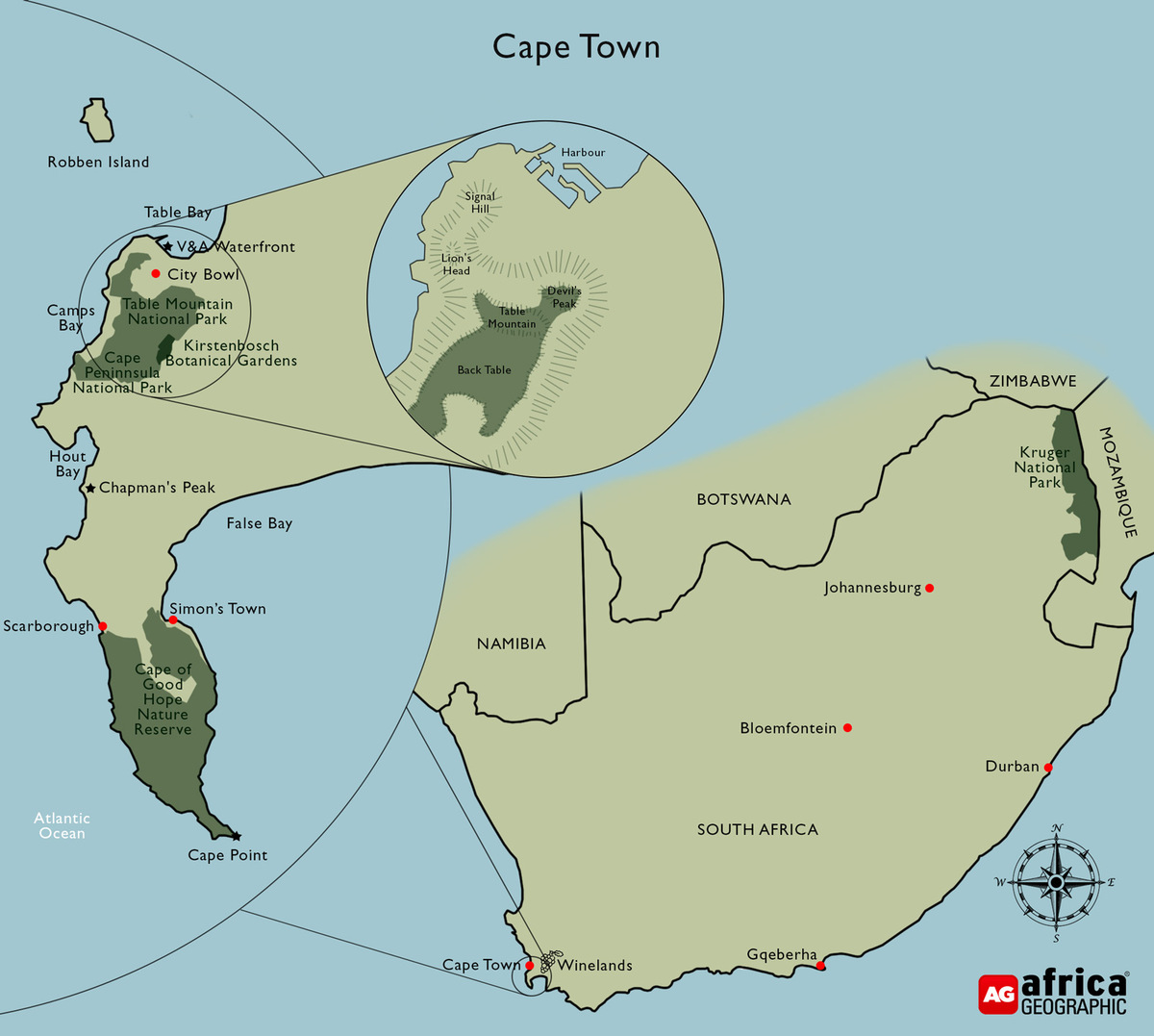

Want to go discover the Garden Route and South Africa while on an African safari?

Want to go discover the Garden Route and South Africa while on an African safari?