The dense, swirling column of Abdim’s and open-billed storks above us pulsed like a sardine bait-ball before dropping to the shallow lake in a g-force-defying stoop, accompanied by an ear-buffeting swoosh to join boisterous pelicans working the fertile fishing grounds.

This is the dry season zenith in north-eastern Zambia’s remote Bangweulu Wetlands, just days before the annual monsoon rains arrive to transform the landscape into a vast inland ocean where the water meets the sky. After a long, hot and dusty day locating a shoebill in dense wetland papyrus beds, I was enjoying a cold beverage on the steps of Shoebill Island Camp, deep in contemplation. The storks were doing their fighter jet thing overhead while fires smouldered on the hazy horizon behind herds of grazing black lechwe, and fishermen plied their trade in the shallows.

You see, this is a different kind of protected area. The owners live here and eke out living fishing, hunting and gathering natural resources – as they have done since before the safari tourism industry was born. And they do so sustainably, albeit with assistance from an exceptional organisation. More about that later.

My travel companion was my close friend and colleague Christian Boix. Christian had dropped off clients in Lusaka after their safari of a lifetime, before joining me. With us in Bangweulu were two siblings, a retired Australian banker and his South African sister. All of us thoroughly enjoyed our brief sojourn to this special place; this was precisely what we were after – responsible tourism in its purest form.

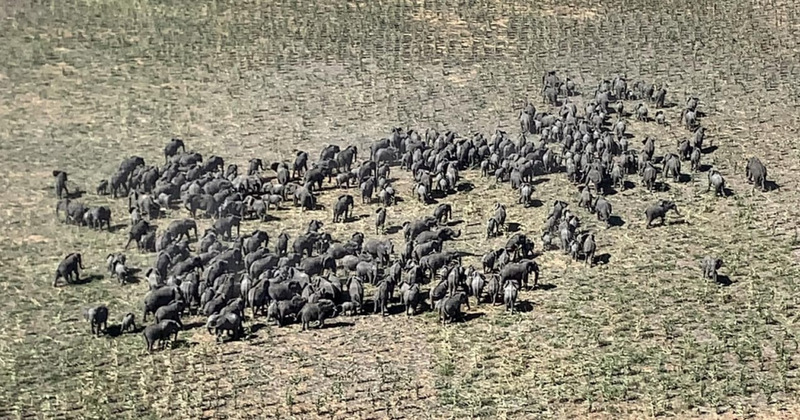

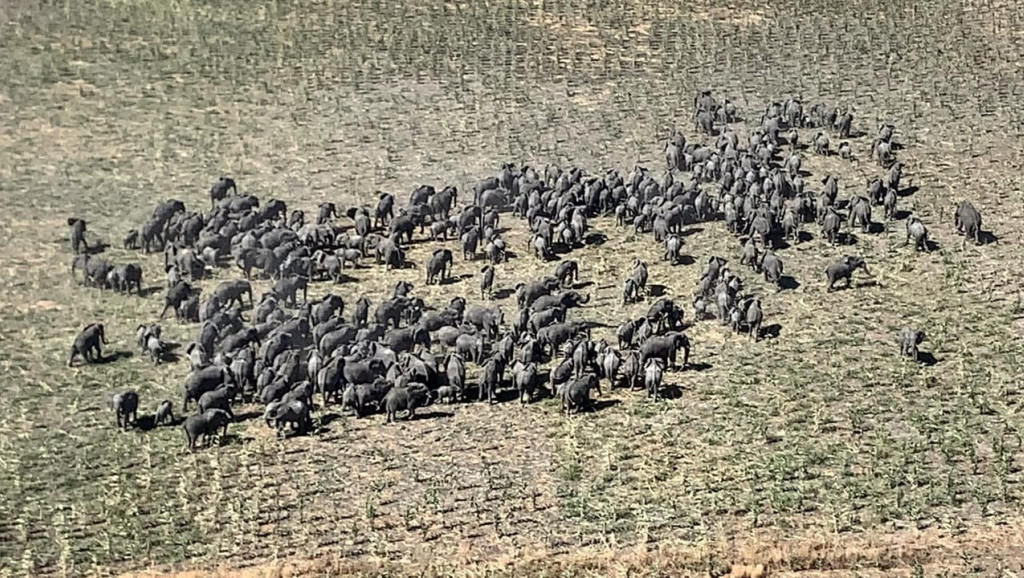

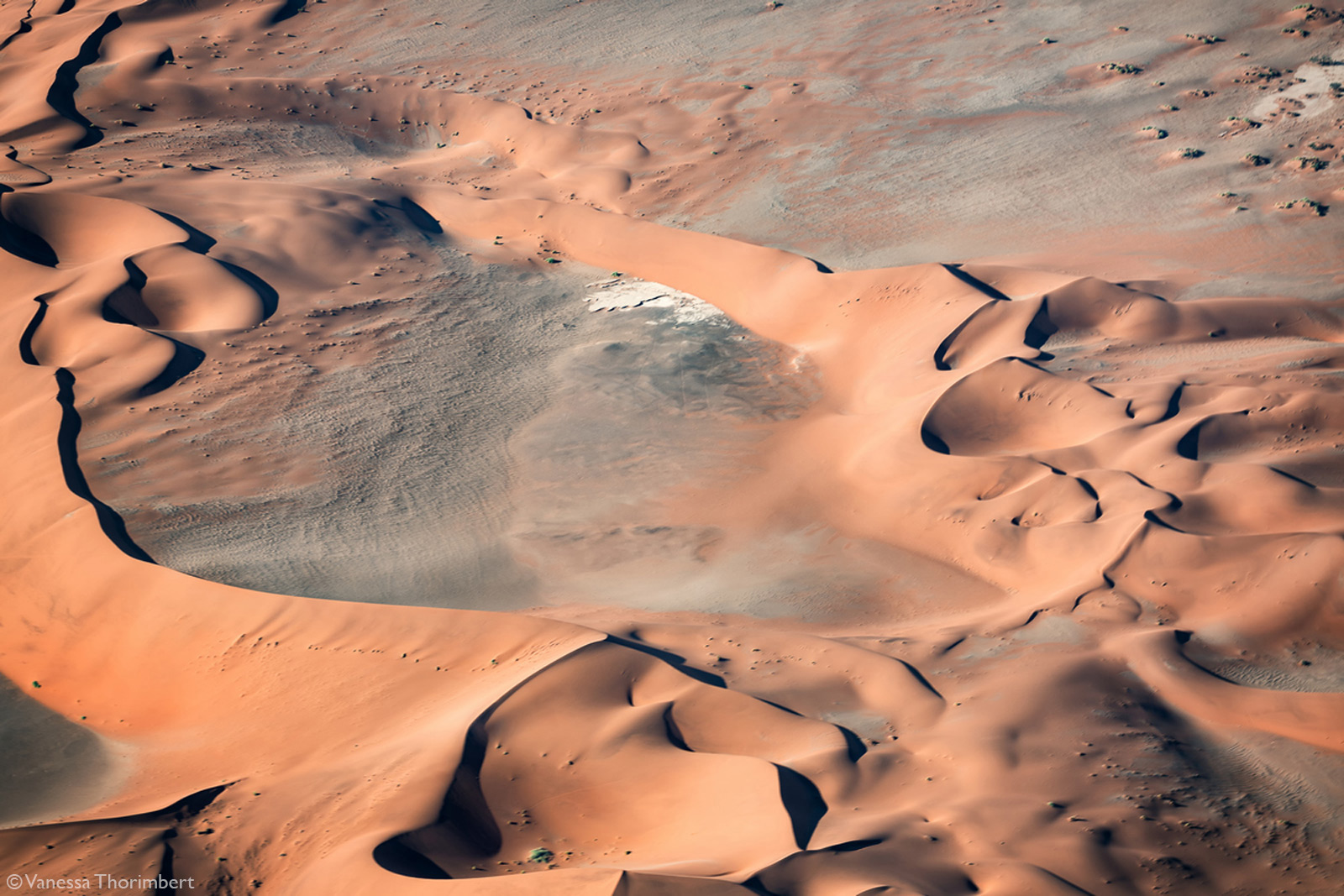

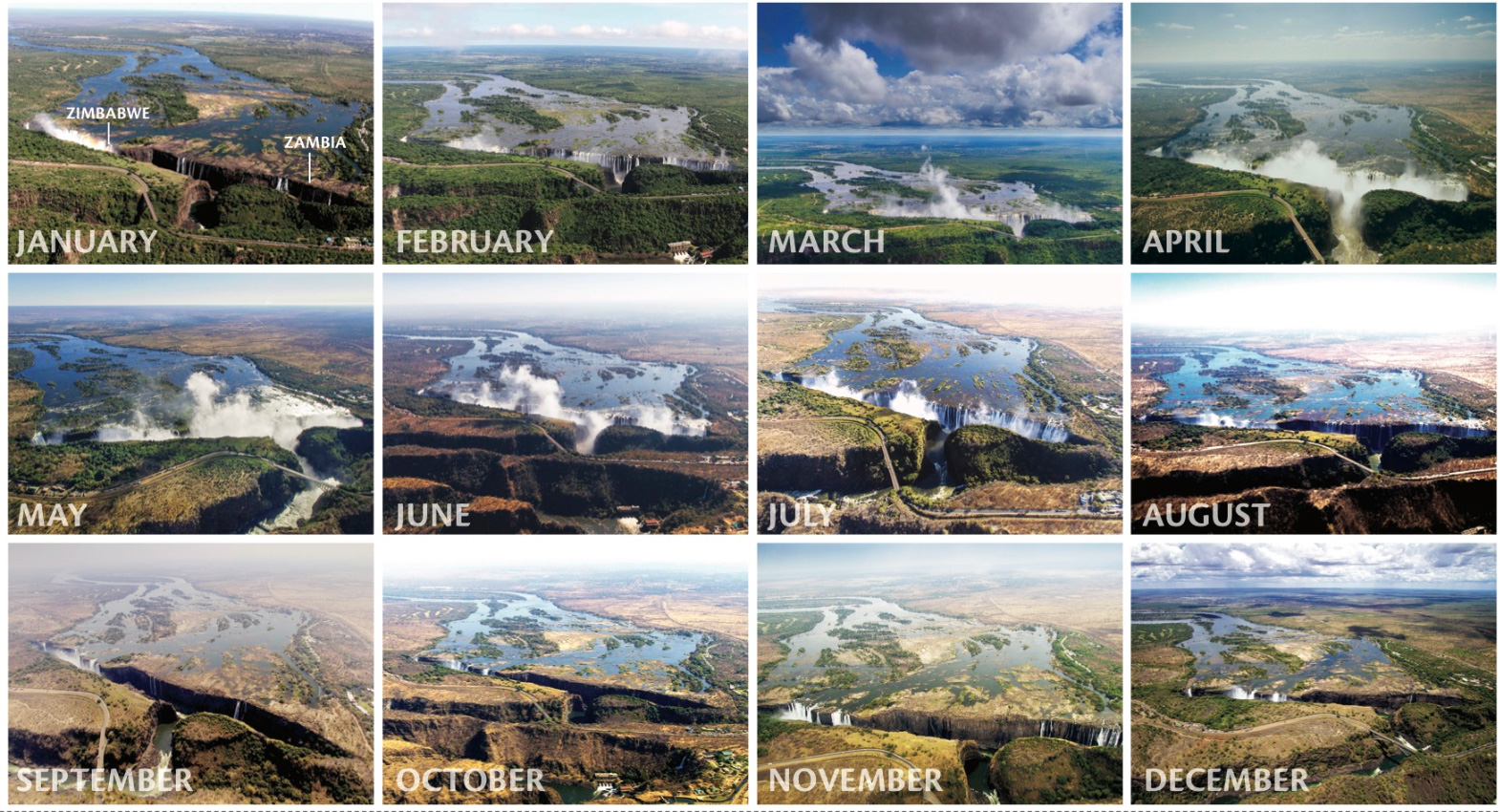

Bird’s-eye view

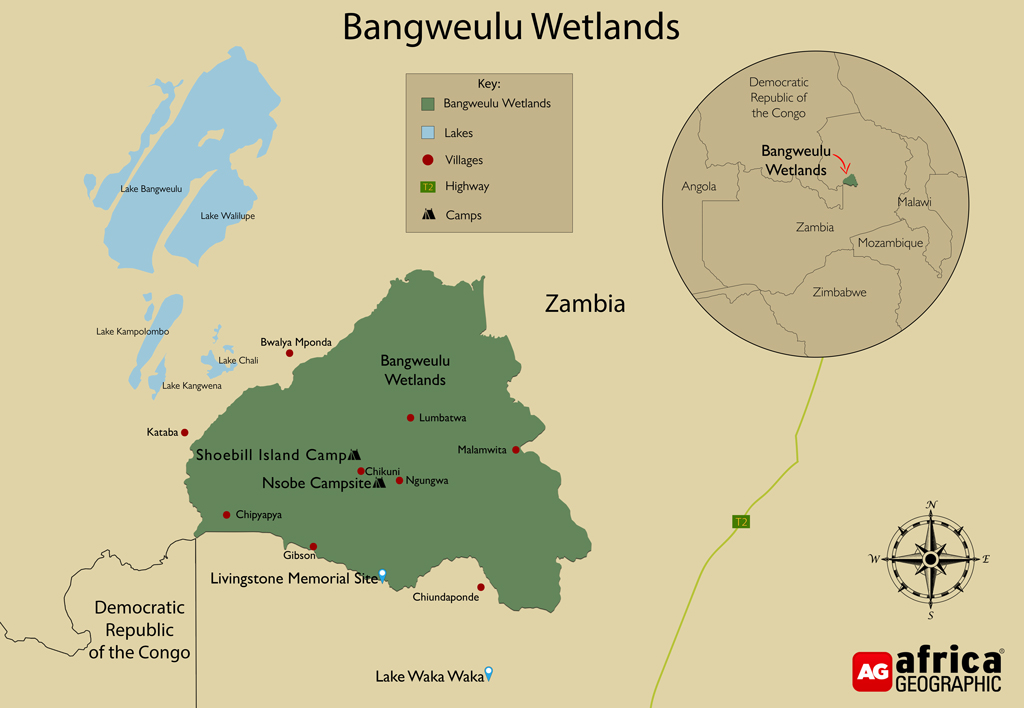

Bangweulu Wetlands consists of floodplains, seasonally flooded grasslands, woodlands and permanent swamps fed by the Chambesi, Luapula, Lukulu and Lulimala rivers. The area has been designated as one of the world’s most important wetlands by the Ramsar Convention, and a BirdLife International Important Bird and Biodiversity Area.

| 9,850 km2 (985,000 hectares) – total size | 6,000 km2 (600,000 hectares) – Managed by African Parks in partnership with Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) and six Community Resource Boards |

| 430 migratory and resident bird species rely on the wetlands | 350 shoebills (6 monitored shoebill nests) |

| 50,000 endemic black lechwe | 50,000 owners (6 chiefdoms) |

The Story of Bangweulu Wetlands

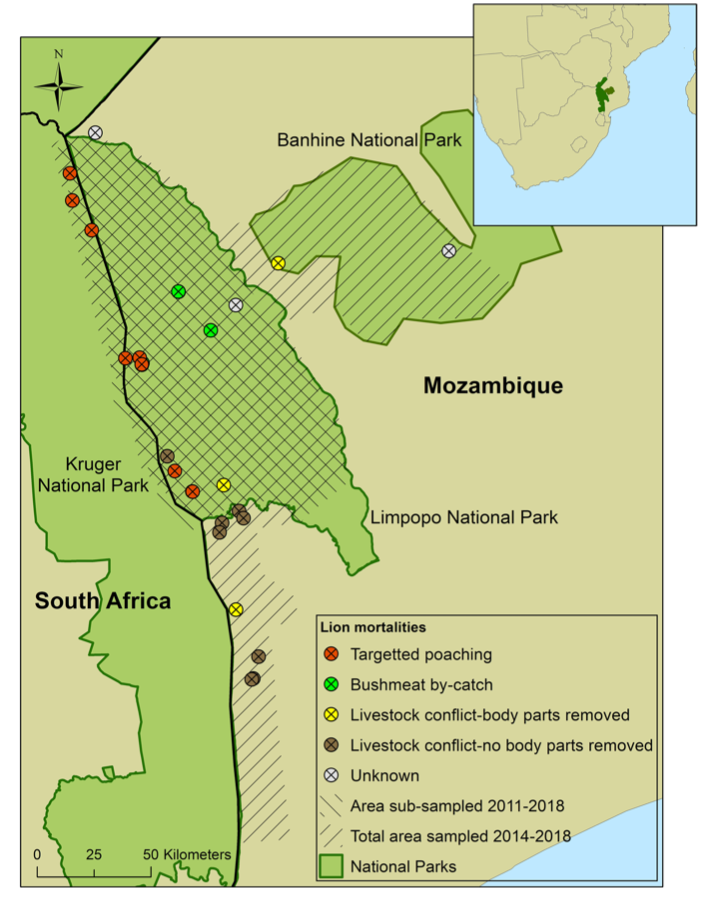

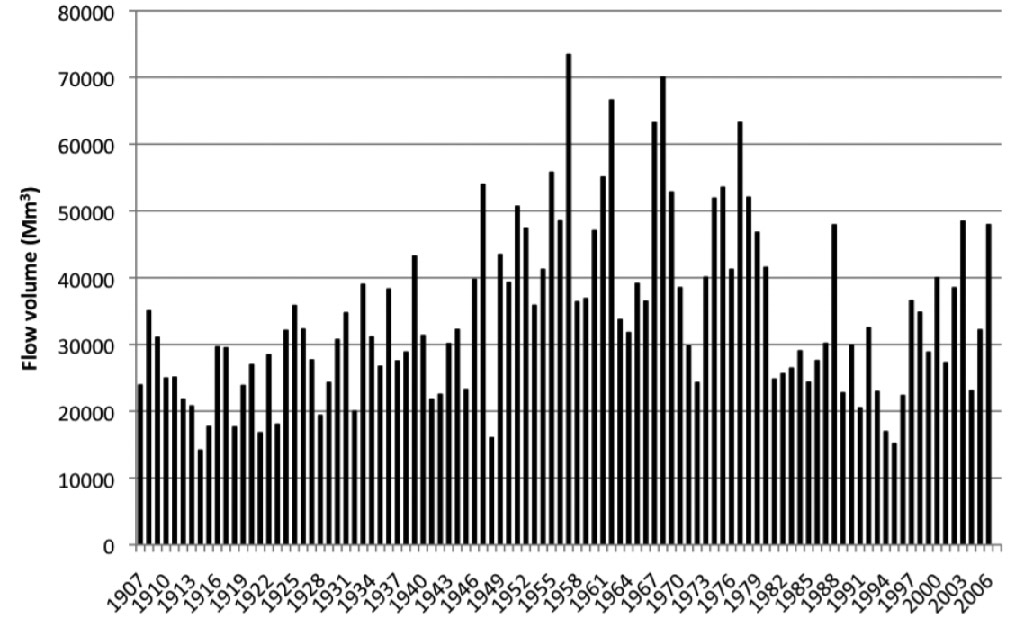

Bangweulu, meaning ‘where water meets the sky’, is home to about 50,000 people who retain the right to harvest its natural resources sustainably and who depend entirely on those resources for their survival. But things were not always as balanced as they are now. Decades of rampant poverty-driven poaching had driven wildlife and fish stocks to the edge, and the community realised that they needed assistance to protect their food sources. They signed a long-term agreement in 2008 with African Parks and Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) and committed to sustainably managing the wetlands to benefit wildlife and people. Since then, bushmeat poaching has been contained, and the endemic black lechwe populations have increased from 35,000 to over 50,000 (estimated carrying capacity is 100,000). Large mammal species such as zebra, impala and buffalo, previously almost exterminated by poaching, have been reintroduced and show steady population increases. Limited quantities of black lechwe, sitatunga and tsessebe are sustainably harvested yearly, earning much-needed revenue (annual target revenue of US$300,000) and protein for local communities. Local community members now guard shoebill nests against the illegal live bird trade because they realise that shoebills are a crucial driver of tourism numbers to this region. Fishermen are adhering to seasonal fishing bans lasting three months to allow stocks to recover, resulting in annual increases in fish stocks, better catch rates and improved economic benefits for communities.

Bangweulu Wetlands is the largest employer in the region, healthcare is being delivered to community members, and 60 schools are supported.

African Parks’ management priorities for Bangweulu are preventing illegal resource harvesting, overfishing, community education and enterprise development to improve livelihoods and build sustainable revenue streams. Their core deliverables revolve around these issues. Managing an area as remote and vast as Bangweulu Wetlands is not easy, and there are ongoing challenges relating to expectation management and law enforcement. Still, compared to the situation before 2008, Bangweulu Wetlands is a shining example of balancing the needs of the people with the preservation of wildlife.

Find out about Zambia for your next African safari. We have ready-made safaris to choose from, or ask us to build one just for you.

Find out about Zambia for your next African safari. We have ready-made safaris to choose from, or ask us to build one just for you.

Bangweulu Wetlands’ continued survival as a sustainable ecosystem depends on its owners deriving lasting benefits whereby they recognise conservation as a viable land-use choice.

Focus on black lechwe

Bangweulu is the only place in the world where you will find wild black lechwe Kobus leche smithemani.

This medium-sized antelope grows to about 1 meter in height and weighs 60 to 120 kilograms (males are 20% larger than females). Only the males have horns. The hindquarters are noticeably higher than the forequarters, and the hooves are elongated and widely splayed – all adaptions to life on soft ground and in water.

Like red lechwe Kobus leche leche and Kafue lechwe Kobus leche kafuensis, black lechwe are slow runners but excellent swimmers and are often seen grazing shoulder-deep in water. Their greasy coats act as waterproofing but also give off a distinctive odour. Black lechwe are classified as vulnerable by IUCN.

Focus on shoebill

The shoebill (Balaeniceps rex) looks like it belongs in the prehistoric age. Found in the marshes of East Africa, the shoebill is classified as vulnerable and is a bucket-list sighting for any avid birder.

Sadly, this iconic species is severely threatened by habitat loss and the illegal bird trade, as the demand for their eggs and chicks places considerable pressure on wild populations. Thankfully, around 350 of these quirky giants find sanctuary in Zambia’s Bangweulu Wetlands, where Yoram Kanokola and other African Parks staff work with dedicated local community members known as ‘Shoebill Guards’ to protect and safeguard nests, ensuring that chicks can safely fledge. Over the last few years, these efforts have helped protect more than 30 fledgelings – ensuring the preservation of the species for generations to come.

For more information about shoebills, read Shoebill – 7 reasons to love this dinosaur of birds.

Explore and stay

Bangweulu is open all year round – but accessibility by road and access to game drive tracks varies depending on water levels.

Shoebill Island Camp was opened in 2018 to generate photographic tourism revenue for Bangweulu Wetlands. Four luxury tents and an impressive open-plan common area nestle under a grove of trees on an island that is reached by boat during the flood season and by a four-wheel-drive vehicle at other times.

Bangweulu also offers self-catering campsites. Nsobe Campsite has six sites for tents, and is located between the Chimbwe woodland and the edge of the swamps.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? Find out more and book your African Parks safari.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? Find out more and book your African Parks safari.

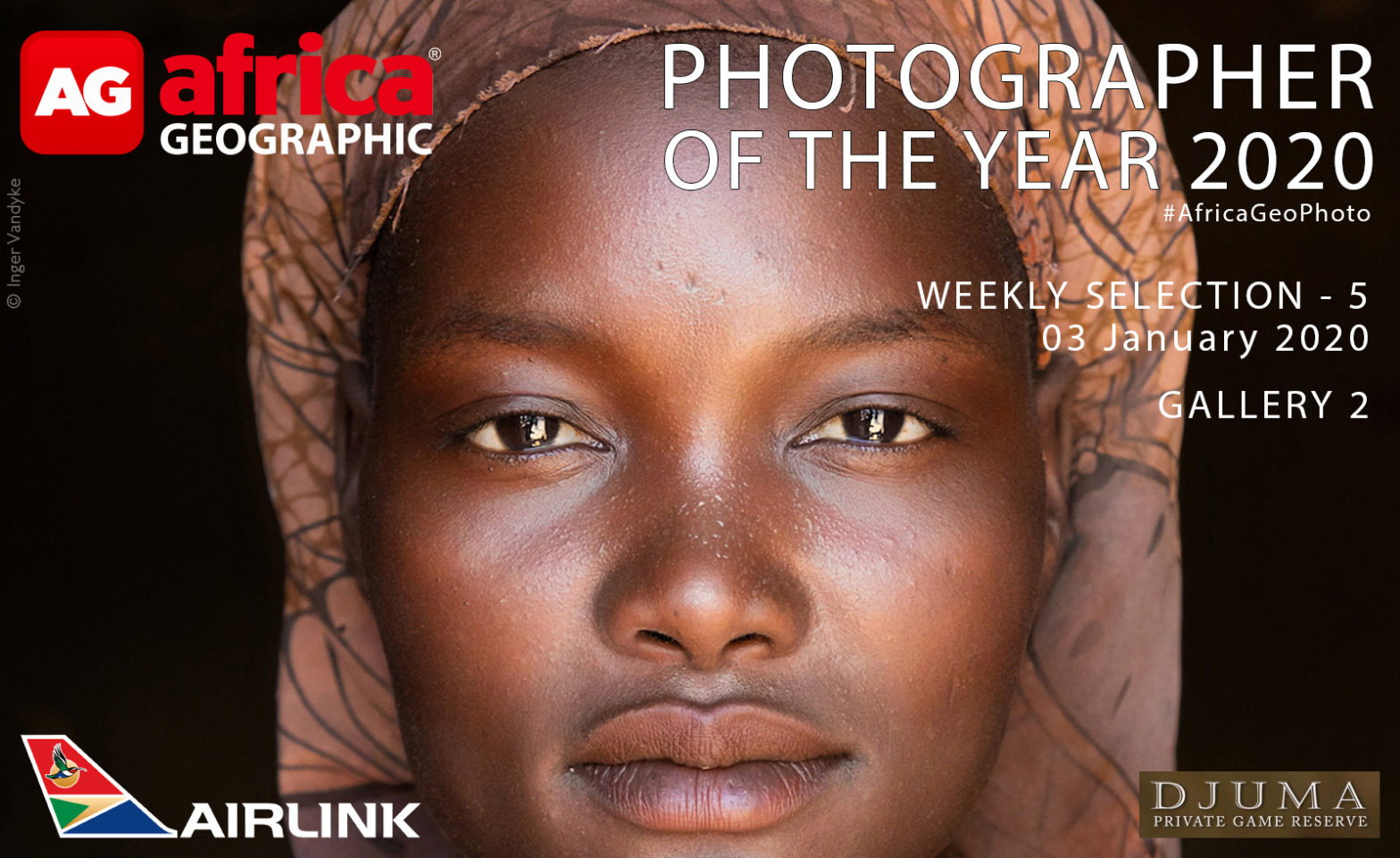

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, SIMON ESPLEY

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’.

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’.

Simon Espley (right) and colleague Christian Boix.

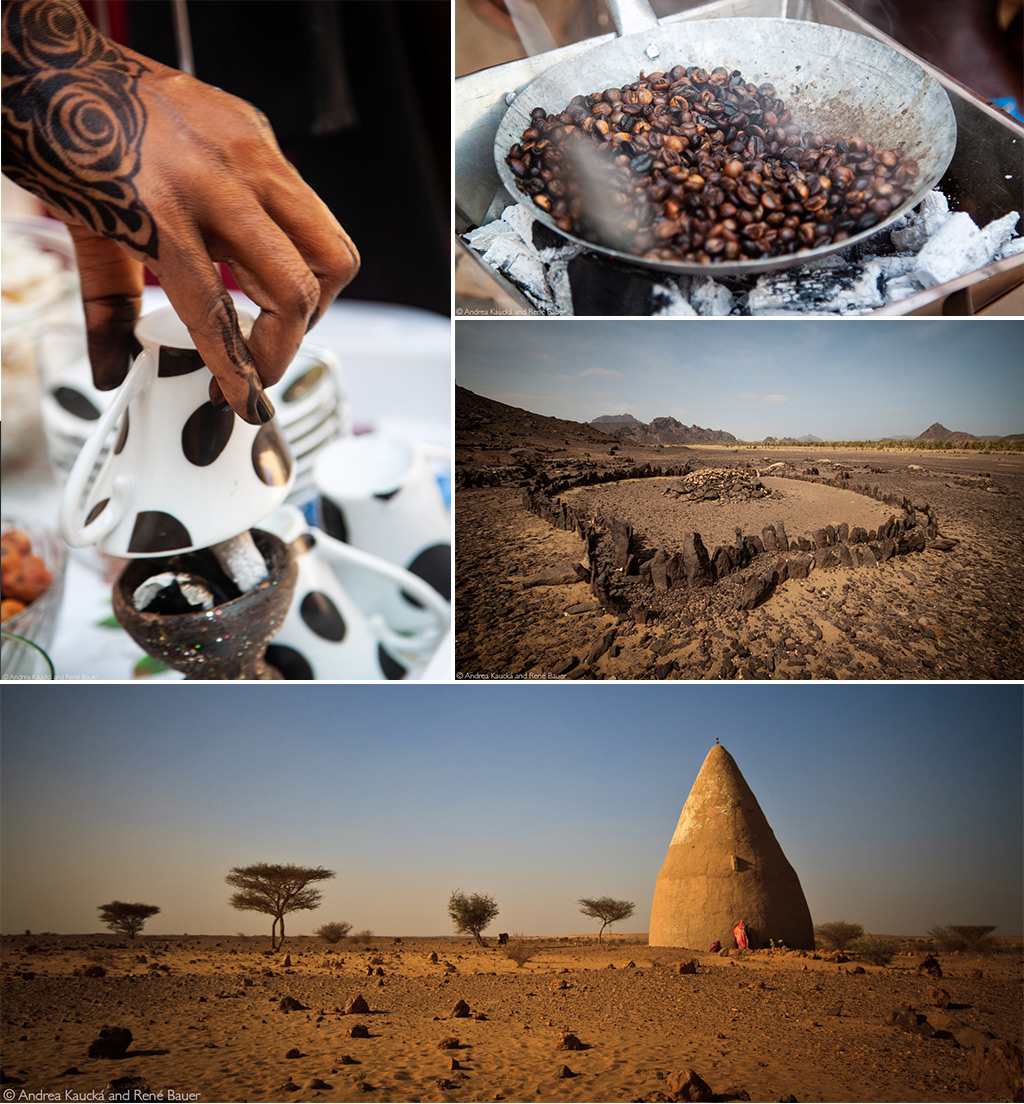

Andrea and René met in New Zealand in 2005. Since then they have worked and travelled in various places in Europe. Their biggest adventure was

Andrea and René met in New Zealand in 2005. Since then they have worked and travelled in various places in Europe. Their biggest adventure was