Rhino horn trade: Leading figures from the African tourism and conservation industries have signed a detailed reply to the advisory committee of South Africa’s Minister of the Environment Barbara Creecy in response to her call for submissions relating to the ongoing review by the committee of trade in elephant, rhino, lion and leopard. This submission has been confirmed as having been received by the committee on Monday 15 June 2020.

To the Chairperson of the Advisory Committee, Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries

15th June 2020

Dear Chairperson and Advisory Committee:

Ref: Response to Notices 221 and 227 in Government Gazette Nos 43173 and 43332 – Submission to the Advisory Committee appointed by the Minister to review the existing policies, legislation and practices related to the management, handling, breeding, hunting and trade of Elephant, Rhino, Lion and Leopard.

This submission responds to the call for submissions issued by the Minister’s Advisory Committee in the Government Gazette as detailed above. It deals specifically with the trade in Rhino horn, although the points made apply equally to important aspects of the Elephant, Lion and Leopard categories.

Before addressing our points, however, we wish to highlight that the Notices (page 1) call for submissions “to review existing policies, legislation and practices relating to the management and breeding, handling, hunting and trade of …. Rhinoceros.” However, the Terms of Reference for the Committee acting as the High-Level Panel (HLP) stipulate (page 3) that it is tasked to:

“… make recommendations relating to….

• Develop the Lobby/Advocacy strategy for Rhino horn trade in different key areas including, but not limited to: …..Identification of new or additional interventions required to create an enabling environment to create an effective Rhino horn trade.”

This clearly indicates that a policy on the trading of Rhino horn has already been decided and that this call for submissions is simply about developing a lobbying and advocacy strategy to facilitate its implementation.

We strongly object to the framing of the call for submissions in this way. No such policy on trade in Rhino horn has been agreed to and it is illegal in terms of international legislation. The wording of the call clearly goes against the spirit of current legislation and begs serious questions as to its underlying purpose.

The remainder of our submission is directed at illuminating the extremely damaging consequences of any legalisation of the trade in Rhino horn – for South Africa’s wild Rhino population, for South Africa’s global tourism offering, and for the large number of poor households who live in the proximity of the country’s Big Five wildlife reserves.

We organise our submission under the following points:

1. The important role of markets – and market failures – in determining conservation outcomes

a) We want to state clearly that the authors of this submission are strong supporters of market-based solutions to conservation challenges. Through the price mechanism and in normal circumstances, free markets have an unrivalled power to incentivise producers and consumers of goods and services to invest and act in ways that maximise positive social (including conservation) outcomes, in their pursuit of private profit. The thriving private lodge industry within and along the borders of our national and provincial parks, the large numbers of predominantly unskilled people it employs and the associated abundance of wildlife there bears ample testimony to this reality.

b) However, ‘market failures’ can occur in any system. As a result of these, the alignment between private and social returns can break down in various ways. When this divergence happens the outcomes of market processes can be extremely damaging and long-lasting. We believe that, for reasons that this submission will outline, fundamental and enduring market distortions and failures underpin the global market for Rhino horn. As a result, any move to legalise this trade, however small and seemingly insignificant on the face of it, will have disastrous consequences for the survival of Rhinos in the wild – both in South Africa and globally.

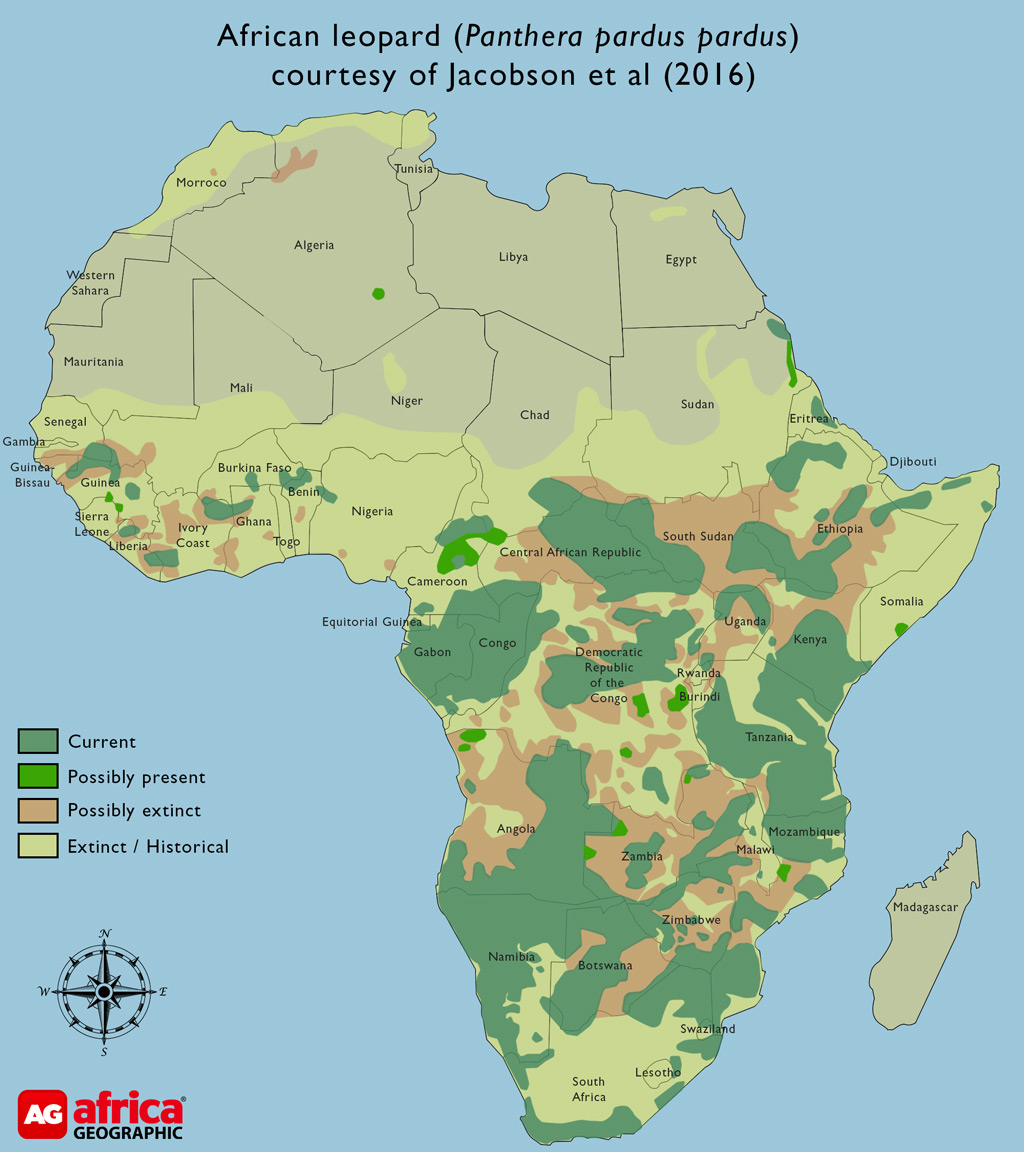

c) Although the market for elephant ivory, lion bone and leopard products differ in important respects from Rhino horn and from one-another, similar market failures apply in these areas too.

2. The demand and supply characteristics of the global market for Rhino horn and their consequences for conservation

a) Demand: In the absence of a legal market for horn, it is impossible to accurately determine the extent or value of global demand. Estimates drawn from pan-African Rhino poaching statistics in the late 1970s suggest that the Asian demand for horn amounted to between 45 tons and as high as 70 tons per year (*1). Since then China has banned the trade and consumption of Rhino horn for use in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)which did dampen demand. But this has subsequently been at least matched by the growth in demand from neighbouring countries, in particular Laos, Vietnam (and now again in China) where the middle and upper classes have expanded enormously over this period. The North Korean state has also clandestinely entered the market for Rhino horn via its Embassies, which uses horn to boost its scarce foreign exchange reserves. It is not unreasonable therefore to assume that global demand could rapidly expand back to the 45 to 70 tons range per year if trade was legalised and demand was re-stimulated (often as a result of the signal that legalisation sends to the market).

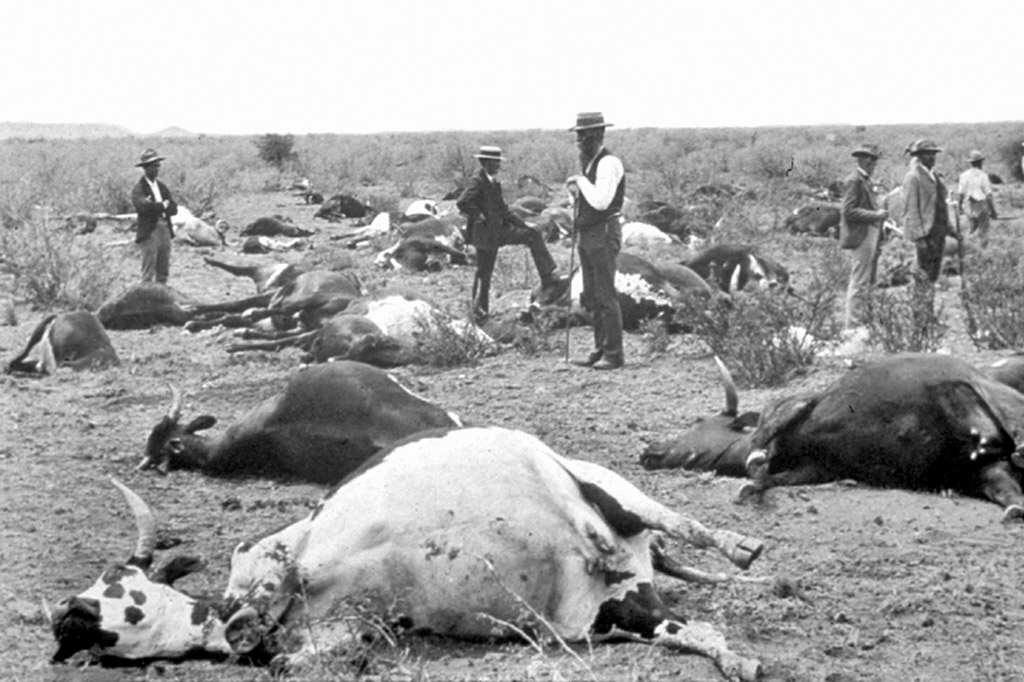

*1 The total number of rhinos in Africa in 1978 was 65,000. The total rhino population in 1987 had plummeted to just 4,000. (Reference: John Hanks Operation Lock page 38 and many journals from that era). 61,000 rhinos were poached in just 9 years, equating to an average of 6,777 rhinos poached each year for each of those 9 years. Average horn set sizes in those days was around 7kgs per rhino which would equate to an average of 47 tons of rhino horn poached each year for 9 years. But towards the end of this period the rhino population was already below 6,777, meaning that a lot more rhinos had to have been poached in 1978 because they were more numerous. Statistically we can therefore calculate that around 70 tons of rhino horn were poached a year in that period around 1978.

b) Supply: A study conducted by the then Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) in 2014 confirmed that the amount of Rhino horn that South Africa could make available annually and sustainably from shavings of farmed Rhino, from existing stocks and future mortalities was then around 2 tons a year, climbing to a maximum of 5 tons a year based on intensive efforts to breed Rhinos (*2). An estimated 16,000 Rhinos exist in SA today, of which maybe around 15% (+2,500) are farmed and the rest are found in our national parks, provincial and private game reserves.

c) The Demand/Supply mismatch and its consequence: Given the enormous gulf that exists between the global potential demand for Rhino horn and the actual maximum possible legal supply – even through intensive breeding and farming – any legalisation of its trade could immediately result in increased actual demand. Assuming intensive captive breeding succeeded in growing the overall supply of horn (i.e. both farmed and wild-deceased) by 10% per year (in itself a highly optimistic assumption), it would take at least thirty five years for the Rhino farming industry to meet the lower level (40 tons p.a.) of this potential annual demand range. The supply lag would take much longer to bridge if (as is highly likely) market demand increased from current levels following legalisation.

As a result, one can anticipate overwhelming demand pressure on any regulated horn supply channel for many years, with obvious inflationary consequences for prices across the board. This would inevitably lead to increased poaching levels of wild Rhinos to meet that demand and to capitalise on the high prices. Instead of helping to reduce poaching levels, legal supply of Rhino horn into the market, however small, would directly incentivise increased poaching of wild Rhinos. As is clear from the evidence, the poaching of wild rhinos is always less expensive than breeding and dehorning (*3). Beyond its impact on the species, this would put SA’s tourism industry, its many related jobs in rural areas and its international reputation at enormous risk.

Some commentators view the spike in prices that would result from legalisation as an opportunity for the SA Government to realise a greater return from its stockpiled reserves, thereby easing its budgetary constraint and enabling enhanced investment in conservation. This is a fallacious and self-defeating argument which would be extremely short-sighted and reckless in light of its consequences for Rhinos in the wild.

*2 https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/rhinohorntrade_southafrica_legalisingreport.pdf

*3 Douglas J Crookes and James N Blignaut, “Debunking the Myth That a Legal Trade Will Solve the Rhino Horn Crisis: A System Dynamics Model for Market Demand,” Journal for Nature Conservation 28 (November 2015): 11–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2015.08.001.

d) Rhino horn price considerations and their consequences: The peak prices that Rhino horn has sold for in the early 2000’s have been around US$60,000 per kilogram, at one point flirting with US$100,000/kg in response to speculative activity. The black-market price for Rhino horn has subsequently dropped to between US$15,000 to US$20,000/kg currently. If demand is re-stimulated, as a result of South Africa legalising the sale of even a portion of its horn stockpile, the black-market price could well revert back to US$60,000 as the market would likely be reactivated.

South Africa’s Private Rhino Owners’ Association (PROA) has proposed a selling price for stockpiled horn in a range between US$10,000 and US$23,000 per kilogram (*4). This translates into a potential premium of the black-market price over regulated supplies of US$ 3,000 to US$ 5,000 (i.e. 15% – 50%) per kilogram. Regardless of the premium, formalising the market at these selling prices would signal the opportunity for massive profits to be made through poaching which is associated with low costs relative to farming (*5).

Given the growth in demand that will undoubtedly follow legalisation and the continuing constrained supply, the price differential between legal and illegal horn supplies will only increase– in both the short and long-term. The price elasticity of demand for Rhino horn (i.e. the extent to which price increases result in a reduction in demand) is demonstrably very low, implying an almost insatiable demand for horn at even the most constrained supply and high price scenarios. Similarly, the price elasticity of supply for horn (the extent to which supply is able to increase in response to higher prices) is low, given the reproduction rates for farmed Rhino (*6).

A context of high demand and constrained legalised supply is a recipe for sustained upward pressure on the price of Rhino horn. This will further incentivise black- market activity aimed at capitalising on rising prices, which will directly manifest in increased poaching. From this, it is clear that, the legalisation of trade will immediately trigger a spiral of black-market activity and poaching, which will not stop for as long as demand exceeds supply – i.e. for many decades. It also runs the risk of driving up speculator activity, where banking on extinction becomes an attractive strategy (*7).

*4 PROA submission to the Advisory Committee of the HLP, 27 May 2020.

*5 Douglas J Crookes, “Does a Reduction in the Price of Rhino Horn Prevent Poaching?,” Journal for Nature Conservation 39 (2017): 73–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2017.07.008.

*6 Crookes and Blignaut, “Debunking the Myth That a Legal Trade Will Solve the Rhino Horn Crisis: A System Dynamics Model for Market Demand.”

*7 Charles F. Mason, Erwin H. Bulte, and Richard D. Horan, “Banking on Extinction: Endangered Species and Speculation,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 28, no. 1 (2012): 180–92, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grs006.

e) The wealth, power and global reach of the criminal syndicates that control the illegal horn trade: The final characteristic of the global Rhino horn market is its control by extremely wealthy, pervasive and corrupt criminal enterprises. These effectively oversee every link in the supply chain, from the point of harvest to trans-shipment, processing and final sale.

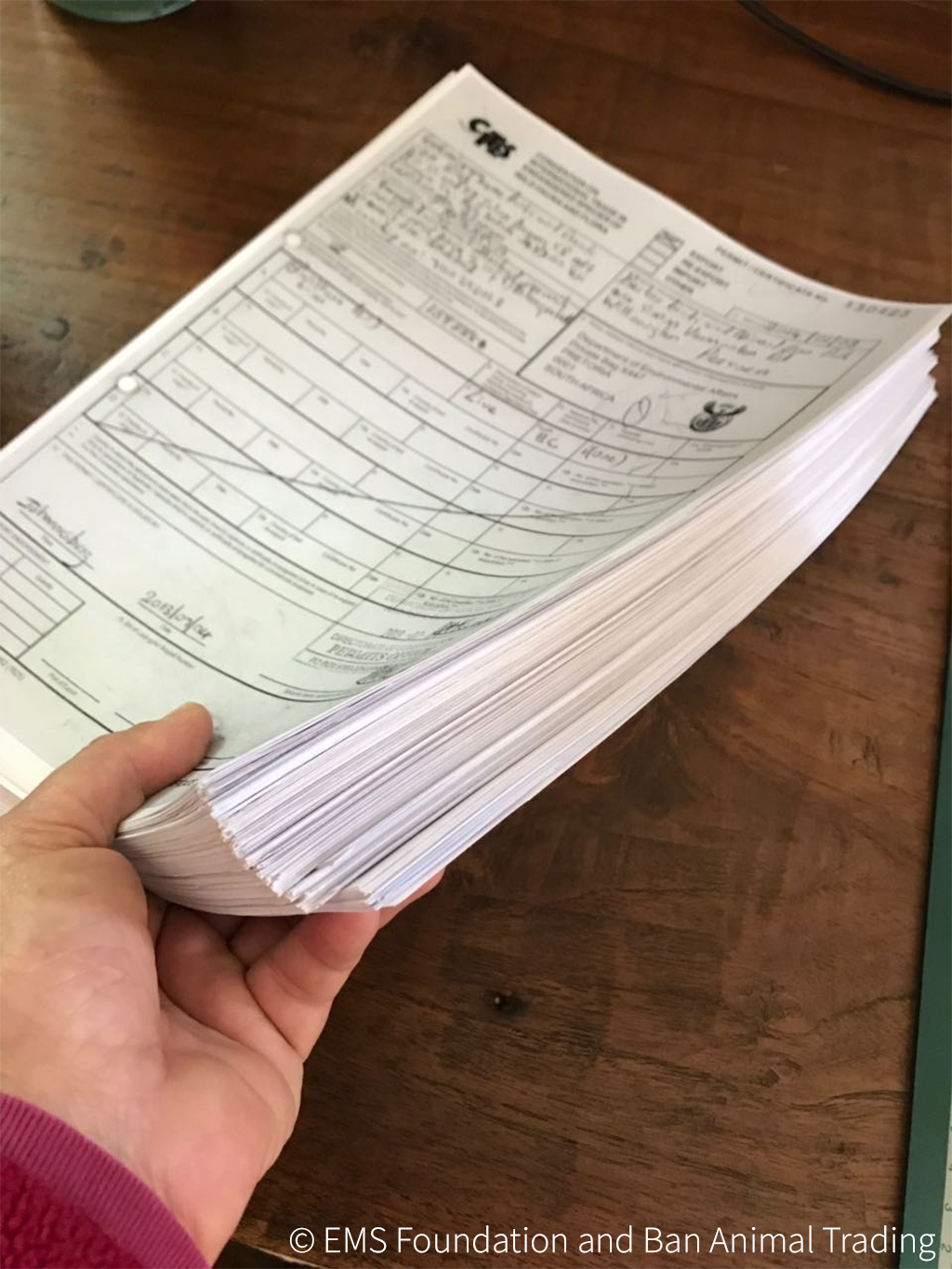

The illegal horn trade is in effect a globally integrated supply chain controlled by extremely rich, agile and powerful criminal syndicates which frequently run parallel enterprises in other wildlife products, narcotics, human trafficking and the like. In this respect it is not dissimilar to the ivory trade (*8). The leverage extends across the regulatory and criminal justice systems that the exposed governments will deploy to oversee any future legal trade.

In the face of these syndicates, the effectiveness of the statutory bodies charged with policing the trade now and in the future are likely to be poor. Under- resourced, weak and vulnerable to corruption at the best of times, these agencies will not be able to hold out against the inducements, intimidation and violence of the interests that control the black market once (if) the lucrative arbitrage opportunities emerge between the illegal and legal trade channels. History clearly shows (see discussion further below) that it is inconceivable for any regulated channel established to control the legalised trade in horn to retain its integrity and not be contaminated by supply from unregulated (illegal) sources given the latter’s wealth and willingness to use it for persuasion (*9).

*8 Ross Harvey, Chris Alden, and Yu Shan Wu, “Speculating a Fire Sale: Options for Chinese Authorities in Implementing a Domestic Ivory Trade Ban,” Ecological Economics 141 (2017): 22–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.017.

*9 Laura Tensen, “Under What Circumstances Can Wildlife Farming Benefit Species Conservation?,” Global Ecology and Conservation 6 (2016): 286–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2016.03.007; Elizabeth L. Bennett, “Legal Ivory Trade in a Corrupt World and Its Impact on African Elephant Populations,” Conservation Biology 29, no. 1 (2014): 54–60, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12377.

f) The consequences of the legalisation of Rhino horn trade on Rhino poaching: Given the supply, demand and price characteristics of the global Rhino horn market, the price disparity between legal and illegal supplies of horn will at the very least continue following the legalisation of any aspect of the trade (*10). This, in turn, will lead directly and without delay to the following:

i. An overwhelming incentive for the criminal syndicates that control illegal supplies of horn to increase their procurement through poaching and related illicit marketing activities, so as to arbitrage the price differential between legal and illegal channels on top of realising the standard large profits from exploiting the difference between the selling price of horn and the cost to poach that horn(*11).

ii. An overwhelming incentive on behalf of poachers at the bottom of the illegal supply chain, most of whom are poor and lack alternative livelihood opportunities, to engage in poaching so as to realise as much value from the neighbouring wildlife resource – regardless of its consequences.

iii. A dramatic acceleration in the poaching of wild Rhinos globally, to the point where they will rapidly disappear outside of small, protected farms and zoos. Is this how tourists will want to view Rhinos when they visit South Africa?

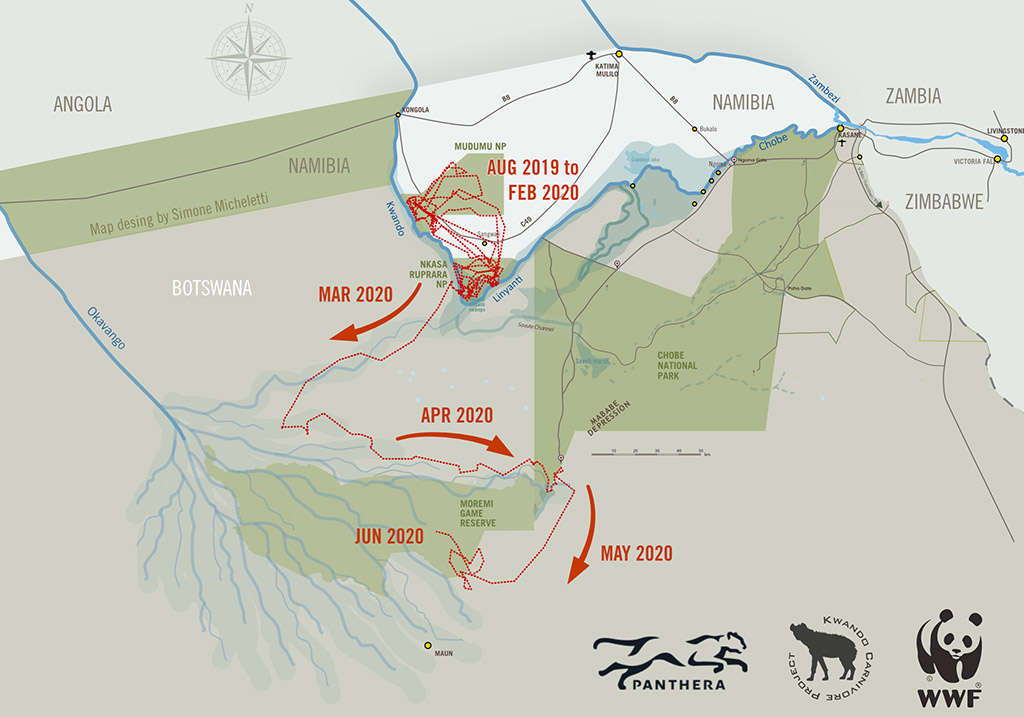

The recent dramatic rise in rhino poaching in Botswana’s Okavango Delta demonstrates how quickly conservation efforts can dissipate when demand is stimulated. The threat from poaching is severe enough to the extent that Botswana is now moving all its last remaining black rhino from the wild to a safe haven well away from the Okavango Delta. Botswana will again have no black rhinos in the wild.

This outcome will be inevitable and unavoidable in South Africa if any aspect of the Rhino horn trade is legalised.

*10 Alejandro Nadal and Francisco Aguayo, “Leonardo’s Sailors: A Review of the Economic Analysis of Wildlife Trade” (Manchester, 2014).

*11 Ciara Aucoin and Sumien Deetlefs, “Tackling Supply and Demand in the Rhino Horn Trade” (Pretoria, 2018), https://enact-africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2018_03_28_PolicyBrief_Wildlife.pdf.

3. Taking account of the lessons from previous legalisation experience

Beyond what market forces dictate will happen, there is clear evidence to be drawn from past experience of what happens when trade in Rhino horn and elephant ivory is legalised, even partially.

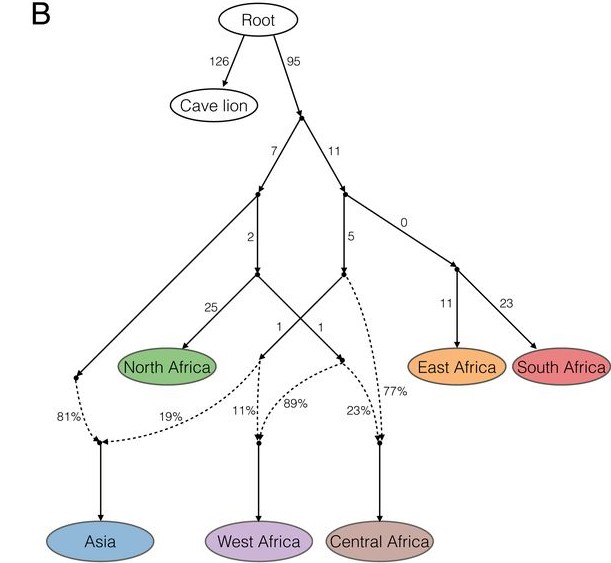

a) The 1993 Rhino horn ban: In a little more than a decade leading up to the Pelly Amendment that led to the full ban on Rhino horn trade in 1993, poaching of Rhinos had decimated the African population from 65,000 (1978) to around 4,000 (1987). Within one year of the full implementation of the worldwide trade ban, demand for Rhino horn plunged, resulting in the incidence of Rhino poaching plummeting to insignificant and manageable levels. The ban worked and the beneficial consequences of the trade ban resulted in over ten golden years for Rhinos – up until the mid-2000s. That was when loopholes in CITES hunting/shipment legislation (by uplifting Southern Africa’s white rhinos to Appendix II etc) were exploited by Vietnamese and other criminal syndicates. The resultant supply immediately re- catalysed demand and reactivated a broader supply chain. This led to the recent rapid and uncontrolled escalation in poaching at enormous cost to both public and private park authorities.

b) The 2008 partial lifting of the elephant ivory ban: Following the precipitous decline in Africa’s elephant population in the 1970s and 80s, a total, loophole proof CITES ivory trade ban was implemented in 1990. Demand for ivory plummeted immediately, and from 1990 for the next fifteen years or so, poaching across Africa diminished to insignificant levels allowing populations to recover. In 2008 CITES gave Southern African states permission to sell 108 tons of ivory to China and Japan. The supply of even small volumes (2 tons per year, in the case of China) into the legal domestic carving market immediately provided the cover for the criminal syndicates to launder illegal, poached ivory into the legal market channel. At the point of sale, there is no means of distinguishing legal from illegal ivory, and very few market players have an interest in finding out. The upshot was that the southern Africa ivory sale re-catalysed the market and demand for ivory in China which in turn triggered a dramatic escalation in poaching in central and west African elephant populations (and Tanzania in particular), where between 20,000 and 30,000 elephants were poached annually across Africa. However, since the Chinese government banned domestic ivory trade at the end of 2017, demand for ivory has dropped and raw ivory prices have plummeted from a high of $2,100/kg in 2014 to around $700/kg today. And with that poaching levels around Africa are starting to ease again.

c) The lessons are clear: even a very proscribed legal trade in an extremely scarce commodity for which there is strong potential demand will dramatically activate that demand by both legitimising the use of that product and catalysing a market for its distribution. This immediately incentivises criminal syndicates to enter the supply chain to profit from laundering their cheaper, illegally procured product into the legal market. Banning all legal trade universally; closing all legal loopholes; eliminating the mixed messages that accompany ongoing debates around legalisation and sending a strong message to the market that all product is illegal in any form, are thus the only means of effectively killing the demand for Rhino horn (and ivory etc). This, in turn, is the only effective means of reducing the threat imposed by poaching to the survival of the species in the wild (*12).

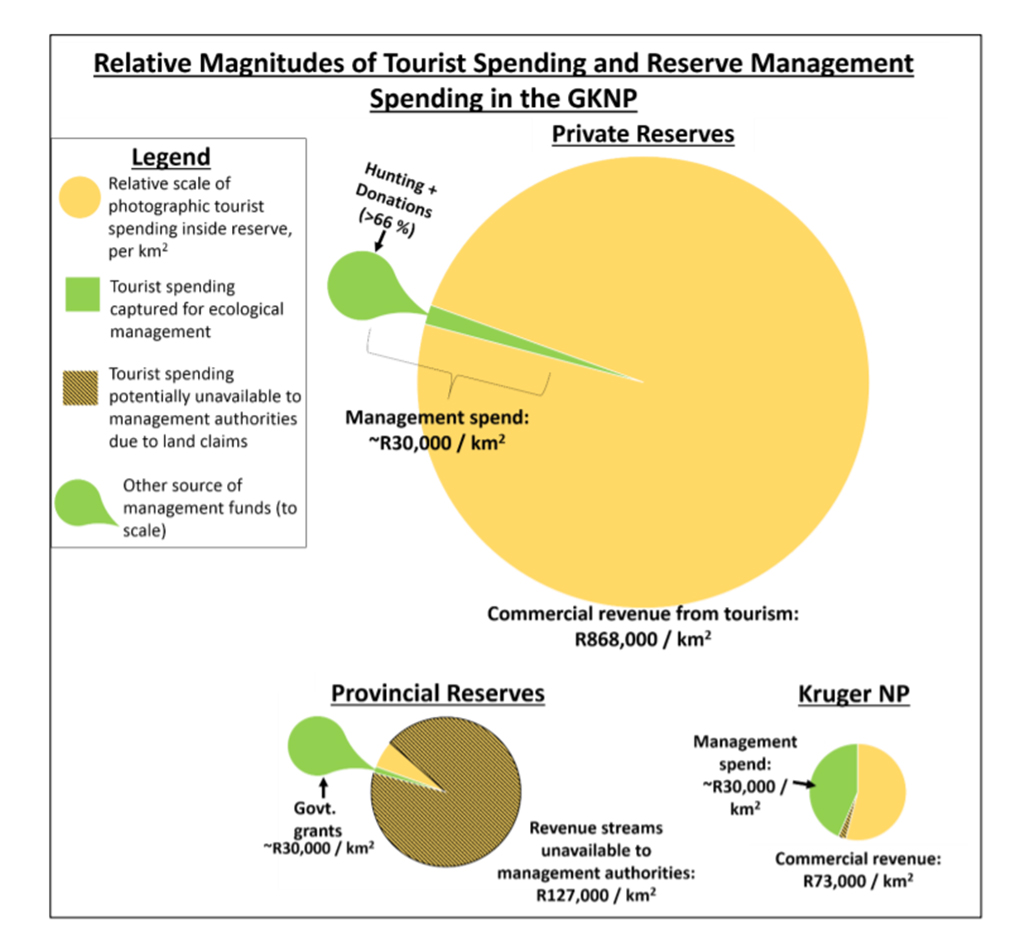

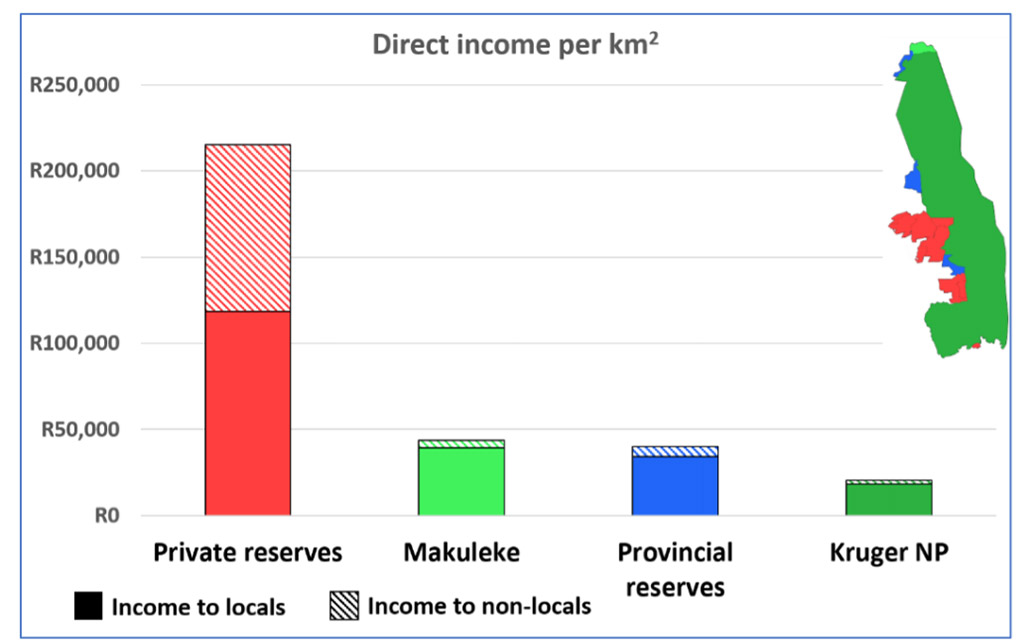

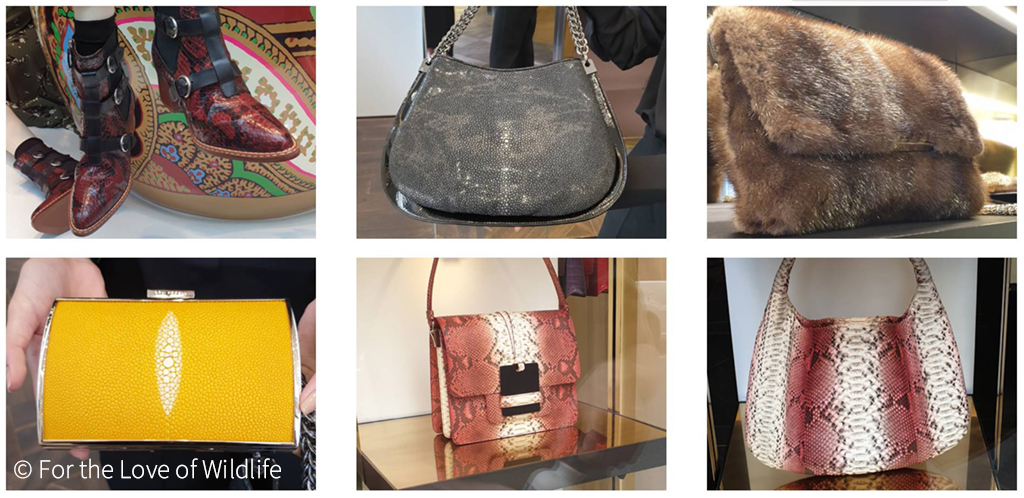

4. The damaging consequences of legalisation for tourism

Pre-Covid, South African tourism had emerged as a key component of a strategy to realise inclusive economic growth. Given its broad base, low entry barriers, high number of women employed (i.e. high number of dependents) and geographical dispersion across deep rural areas, tourism presents a unique opportunity for small business creation, low-skilled labour-intensive growth and enhanced foreign exchange earnings. Up to 80% of international tourists to SA are drawn by South Africa’s wildlife offer in tandem with the Cape. Market research has shown that these tourists are overwhelmingly opposed to hunting and / or trade in endangered species and products in line with global trends. Tourism would be gravely affected if we were to lose our Rhinos in the wild – i.e. if SA would became a ‘Big Four’ safari destination (*13). The attractiveness of South Africa as a safari destination would be seriously and negatively compromised by any move to legalise the Rhino horn trade.

Both the public sector and the private sector of South Africa’s wildlife economy are overwhelmed by the costs associated with anti-poaching security. Any legalisation of the Rhino horn trade would immediately exacerbate these costs as poaching levels would escalate to even higher levels than the current situation as the demand for illegal horn would ramp up to meet the high value market- arbitrage and / or profit opportunities that would emerge from legalised trade.

The appeal from this submission to the HLP is to recognise that it is far more prudent and rewarding for the SA Government to invest in the protection and re-growth of the traditional tourism industry which at its pre-Covid peak was worth over R120 billion annually (and supported the livelihoods of one in seven South Africans), than risk much of that to support an unproven industry that is worth less than 1% of that and will benefit a very small number of people.

Post-Covid, Brand South Africa must cultivate to successfully capitalise on the re-emergence of the global travel market is that of an ethical wildlife destination, uncompromised by any associations with criminality and exploitation. These negative associations will unavoidably accompany any legalisation of the Rhino horn trade.

*12 Ross Harvey, “Risks and Fallacies Associated with Promoting a Legalised Trade in Ivory,” Politikon, June 27, 2016, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2016.1201378; Harvey, Alden, and Wu, “Speculating a Fire Sale: Options for Chinese Authorities in Implementing a Domestic Ivory Trade Ban.”

*13 Clarissa van Tonder, Melville Saayman, and Waldo Krugell, “Tourists’ Characteristics and Willingness to Pay to See the Big Five,” Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 2013, www.stoprhinopoaching.com.

5. The alternatives to legalisation

There is only one alternative to the legalisation of any aspect of the Rhino horn trade, and that is an absolute ban on the trade globally and domestically, in any and all of its manifestations.

If the Government wanted to be really innovative and raise considerable amounts of money for South Africa’s fiscus to fund the running costs of South Africa’s National Parks and provincial game reserves, this ban should be accompanied by the destruction of existing publicly and privately held rhino horn stockpiles. This could be undertaken through a widely publicised, high profile, celebrity-endorsed Rhino horn ‘burning event’ in the Kruger National Park (*14). This could serve as a worldwide rallying and fund raising event to raise money for conservation by asking the world to ‘buy’ the rhino horn that was about to be burnt through donations both big and small. The money raised would be shared proportionally between SANParks and the private sector according to their respective horn contributions to the burn. This event would also create much needed positive worldwide publicity for South Africa that would enhance our ethical brand and entice many more tourists to visit the country. Such an event would be an unequivocal win for all stakeholders – Rhino conservation, for SA’s parks, for tourism to South Africa and for SA’s fiscus.

Importantly, the Burn in tandem with a significant worldwide demand reduction campaign would simultaneously send a powerful message to Rhino horn traders, processors, criminals and consumers alike that there is no prospect of ever sourcing horn supply on any meaningful scale, and that Rhino horn no longer had any value. While this would obviously not completely stop the illegal trade in and use of horn, it would:

1. eliminate once and for all the mixed messaging and the associated forward planning by the black-market participants in the supply chain, in anticipation of some form of trade relaxation, and as a direct result

2. reduce poaching considerably to manageable levels (along the lines of the 1993 ban on rhino horn trade) to well below the birth rates of Rhinos in the wild.

Together with more, and more effective, demand management initiatives in Asian markets– including the post-Covid attention and commitment that will undoubtedly be directed by governments and agencies at eliminating the trade and sale of wild animals – these actions offer the best prospects of permanently eliminating the market for horn. Only through these interventions and their market-collapsing outcomes will the future of Rhinos in the wild be secure (*15).

*14 Chris Alden and Ross Harvey, “The Case for Burning Ivory,” Project Syndicate, 2016,

*15 Ross Harvey, “South Africa’s Rhino Paradox,” Project Syndicate, 2017

6. The urgent need for clear and consistent communication by the SA Government

We cannot over-emphasise the extremely damaging consequences for Rhino conservation of the on- going debates – and the mixed messages that they feed across the value chain – around legalisation of the trade in horn. Just as any form of legal trade may stimulate demand by legitimising the use of the product, continued mixed messaging which references the scope for future trade (on whatever scale), keeps the supply chain and its participants alive: exploring loopholes, raising stockpiles, lobbying stakeholders, corrupting security personnel and paying poachers.

7. Dispelling some of the myths deployed by the lobby for legalisation of trade

A number of enduring ‘logical’ sounding myths have been created and continue to be perpetuated to bolster arguments to legalise trade of Rhino horn, elephants, lions and leopards. These myths are highlighted and answered briefly, in no particular order, below. We urge the Panel not to be persuaded by any of these unfounded arguments.

a) Ostriches and crocodiles were saved from extinction through commercial farming- their success should be replicated and applied to Rhinos via the commercialisation of the horn trade and the promotion of Rhino farming.

There are no parallels between the crocodile/ostrich value chains and Rhinos, and therefore no lessons to be drawn to support the legalisation of trade in horn. Female ostriches can produce upwards of 40 chicks per year and crocodiles around 60 hatchlings per year which compounded over five generations equates to over 100 million animals. A mature female Rhino will produce one calf every two and a half years and very few over her lifetime. Starting from the current stock of farmed animals, commercial Rhino farming will, on very optimistic assumptions, take at least 30 years to meet current levels of demand. Given the huge disparity between demand and supply for horn and its impact on prices, Africa’s wild Rhinos will be extinct well before the point when stocks of farmed Rhino are remotely able to satisfy world demand. Moreover, Asian consumers prefer wild over farmed products when there is a medicinal use because of the belief that wild products have more potency (*16). Commercial farming of Rhinos thus offers no solution to the poaching crisis.

b) Exclusive government to government selling channels can be established to regulate trade and neutralise the black market.

The countries most likely to be involved in such arrangements have a very poor record with regard to enforcement. The integrity of these channels will never be maintained in the face of the sustained attack that will be directed at them from rich and generous criminal syndicates, many of which have infiltrated these organisations anyway. As has been illustrated, the establishment of legal trade channels does nothing to displace illegal channels. On the contrary, it incentivises their expansion. Illegal supply channels are difficult enough to police effectively. This ask is made all the more difficult when they are given cover by parallel legal channels whose end-markets are indistinguishable (*17).

*16 Tensen, “Under What Circumstances Can Wildlife Farming Benefit Species Conservation?”

*17 Alan Collins, Gavin Fraser, and Jen Snowball, “Issues and Concerns in Developing Regulated Markets for Endangered Species Products: The Case of Rhinoceros Horns,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 40, no. 6 (2016): 1669–86, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bev076.

c) Funds raised through commercial farming and trade can be used to finance conservation and community development.

Beyond the minimal growth in labourer level employment that could result from increased farming (if any), there will be very little benefit for communities that live around South Africa’s wildlife reserves or for conservation programmes – or for the national treasury. One must ask whether sable, buffalo colour variant breeding, Rhino or other game farming has ever materially benefited communities or conservation around South Africa’s national parks?

But those activities have clearly created genetic risks and undermined the country’s reputation (*18). Moreover, as was revealed by the sale of ivory stocks in 2008, the proceeds of such sales do not get ring-fenced within treasury for ploughing back into conservation, security and ‘community development’ as is so often alleged. They are absorbed into the general appropriation account.

d) There are parallels to be drawn between banning trade in Rhino horn and banning sales of cigarettes during Covid19 – bans will never be effective.

There are no parallels between Rhino horn bans and cigarette or alcohol bans. The latter are widely consumed, repeat-use, involving habits which, within certain regulatory limits, are fully legal. Banning them will give rise to widespread popular resistance and rampant black-market transactions. Rhino horn trade and use is limited to specific market niches globally, beyond which they are widely shunned. While banning all trade in and the use of Rhino horn will possibly result in some initial black market activity, this will be on an insignificant and diminishing scale the longer the ban and the attendant demand reduction campaigns and negative social messaging is maintained (*19). It should be remembered that history has proven that loophole free rhino horn (and ivory) trade bans have indeed worked.

e) We should pursue a pilot project around legalisation. If it doesn’t work the ban can be re-imposed.

We already know from past experience that legalising trade, whether in horn or ivory, does not stop poaching; it accelerates it. If South Africa sold Rhino horn to the Asian market for a few years with a view to stopping if those sales did not stop poaching, the effects on our wild Rhino populations would be devastating. The few years of legal sales will serve merely to create the long-term cover under which the trade in poached Rhino horn will thrive. SA’s once-off ivory sale to China in 2008 proved that once a legal market exists, the legally obtained tusks provided lengthy legal cover for poached ivory to be easily laundered into the market masquerading as the legal product (*20). Fundamentally, as we know, there are not enough Rhinos in the wild to start recklessly testing unproven pro-trade economic models in complex, fast growing and corrupt Asian markets with rapidly increasing numbers of wealthy consumers. By the time the unintended (but entirely predictable) consequences of legalisation are recognised, and steps taken to reverse them, there is every likelihood that the world will have lost its wild Rhino population. Forever.

*18 Jeanetta Selier et al., “An Assessment of the Potential Risks of the Practice of Intensive and Selective Breeding of Game To Biodiversity and the Biodiversity Economy in South Africa,” 2018.

*19 https://theconversation.com/what-is-the-wildlife-trade-and-what-are-the-answers-to-managing-it-136337, accessed 14 June 2020.

*20 Harvey, Alden, and Wu, “Speculating a Fire Sale: Options for Chinese Authorities in Implementing a Domestic Ivory Trade Ban.”

8. Conclusion

We trust that this submission and the comparative global experience it draws on shows beyond any doubt that the legalisation, even partially or temporarily, of any aspect of the global Rhino horn trade will do immediate and lasting damage to the prospects for the survival of Rhinos in the wild.

Similarly, selling or auctioning off existing stockpiles of Rhino horn is not a viable option to solve our Rhino poaching scourge. If South Africa did trade its Rhino horn, a handful of players who control existing stockpiles and who control the global supply chain would become very wealthy. But this would be at the expense of SA’s wild Rhino population whose demise may follow very quickly as the global market expanded and as the criminal syndicates who control it set about arbitraging the price differentials between any regulated market and the international black market.

In a nutshell, the specific demand, supply and criminal characteristics of this market mean that even a partial legalisation of trade in horn will create massive poaching pressure on the remaining wild population which will be impossible to contain.

The time has come for the Minister to take a pragmatic decision for the long term benefit of Rhinos in the wild, for South African tourism and for the rural communities whose livelihoods depend on the wildlife economy of banning outright all trade forever in all Rhino horn and ivory (and indeed lion and leopards).

In the light of the evidence, we urge the DEFF to entrench the ban on any trade in Rhino horn both domestically and internationally. We also urge it to be bold in communicating a single, unambiguous message to the world: that it will not countenance any change in this policy. There would be no more effective way to communicate this message and effectively eliminate any speculation in the market regarding future sales, for it to publicly destroy its available Rhino horn stockpile.

References and further reading:

Alden, Chris, and Ross Harvey. “The Case for Burning Ivory.” Project Syndicate, 2016.

Aucoin, Ciara, and Sumien Deetlefs. “Tackling Supply and Demand in the Rhino Horn Trade.” Pretoria, 2018. https://enact- africa.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/2018_03_28_PolicyBrief_Wildlife.pdf.

Bennett, Elizabeth L. “Legal Ivory Trade in a Corrupt World and Its Impact on African Elephant Populations.” Conservation Biology 29, no. 1 (2014): 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12377.

Collins, Alan, Gavin Fraser, and Jen Snowball. “Issues and Concerns in Developing Regulated Markets for Endangered Species Products: The Case of Rhinoceros Horns.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 40, no. 6 (2016): 1669–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bev076.

Crookes, Douglas J. “Does a Reduction in the Price of Rhino Horn Prevent Poaching?” Journal for Nature Conservation 39 (2017): 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2017.07.008.

Crookes, Douglas J, and James N Blignaut. “Debunking the Myth That a Legal Trade Will Solve the Rhino Horn Crisis: A System Dynamics Model for Market Demand.” Journal for Nature Conservation 28 (November 2015): 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2015.08.001.

Harvey, Ross. “Risks and Fallacies Associated with Promoting a Legalised Trade in Ivory.” Politikon, June 27, 2016, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2016.1201378.

“South Africa’s Rhino Paradox.” Project Syndicate, 2017.

Harvey, Ross, Chris Alden, and Yu Shan Wu. “Speculating a Fire Sale: Options for Chinese Authorities in Implementing a Domestic Ivory Trade Ban.” Ecological Economics 141 (2017): 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.017.

Hsiang, Solomon, and Nitin Sekar. “Does Legalization Reduce Black Market Activity? Evidence from a Global Ivory Experiment and Elephant Poaching Data.” NBER Working Paper. Cambridge, MA, June 2, 2016. http://www.nber.org/papers/w22314.pdf.

Mason, Charles F., Erwin H. Bulte, and Richard D. Horan. “Banking on Extinction: Endangered Species and Speculation.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 28, no. 1 (2012): 180–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grs006.

Nadal, Alejandro, and Francisco Aguayo. “Leonardo’s Sailors: A Review of the Economic Analysis of Wildlife Trade.” Manchester, 2014.

Sekar, Nitin, William Clark, Andrew Dobson, Paula Cristina Francisco Coelho, Phillip M. Hannam, Robert Hepworth, Solomon Hsiang, et al. “Ivory Crisis: Growing No-Trade Consensus.” Science 360, no. 6386 (2018): 276–77. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat1105.

Selier, Jeanetta, Lizanne Nel, Ian Rushworth, Johan Kruger, Brent Coverdale, Craig Mulqueeny, and Andrew Blackmore. “An Assessment of the Potential Risks of the Practice of Intensive and Selective Breeding of Game To Biodiversity and the Biodiversity Economy in South Africa,” 2018.

Tensen, Laura. “Under What Circumstances Can Wildlife Farming Benefit Species Conservation?” Global Ecology and Conservation 6 (2016): 286–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2016.03.007.

Tonder, Clarissa van, Melville Saayman, and Waldo Krugell. “Tourists’ Characteristics and Willingness to Pay to See the Big Five.” Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 2013. www.stoprhinopoaching.com.

For further reading see:

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2019-10-15-trading-in-rhino-horn-is-not-going-to- solve-our-extinction-crisis/

https://theconversation.com/why-allowing-the-sale-of-horn-stockpiles-is-a-setback-for-rhinos-in- the-wild-82773

https://www.africaportal.org/features/locking-horns-save-rhino/

Nick is an award-winning wildlife photographer, author, photographic guide and conservationist.

Nick is an award-winning wildlife photographer, author, photographic guide and conservationist.

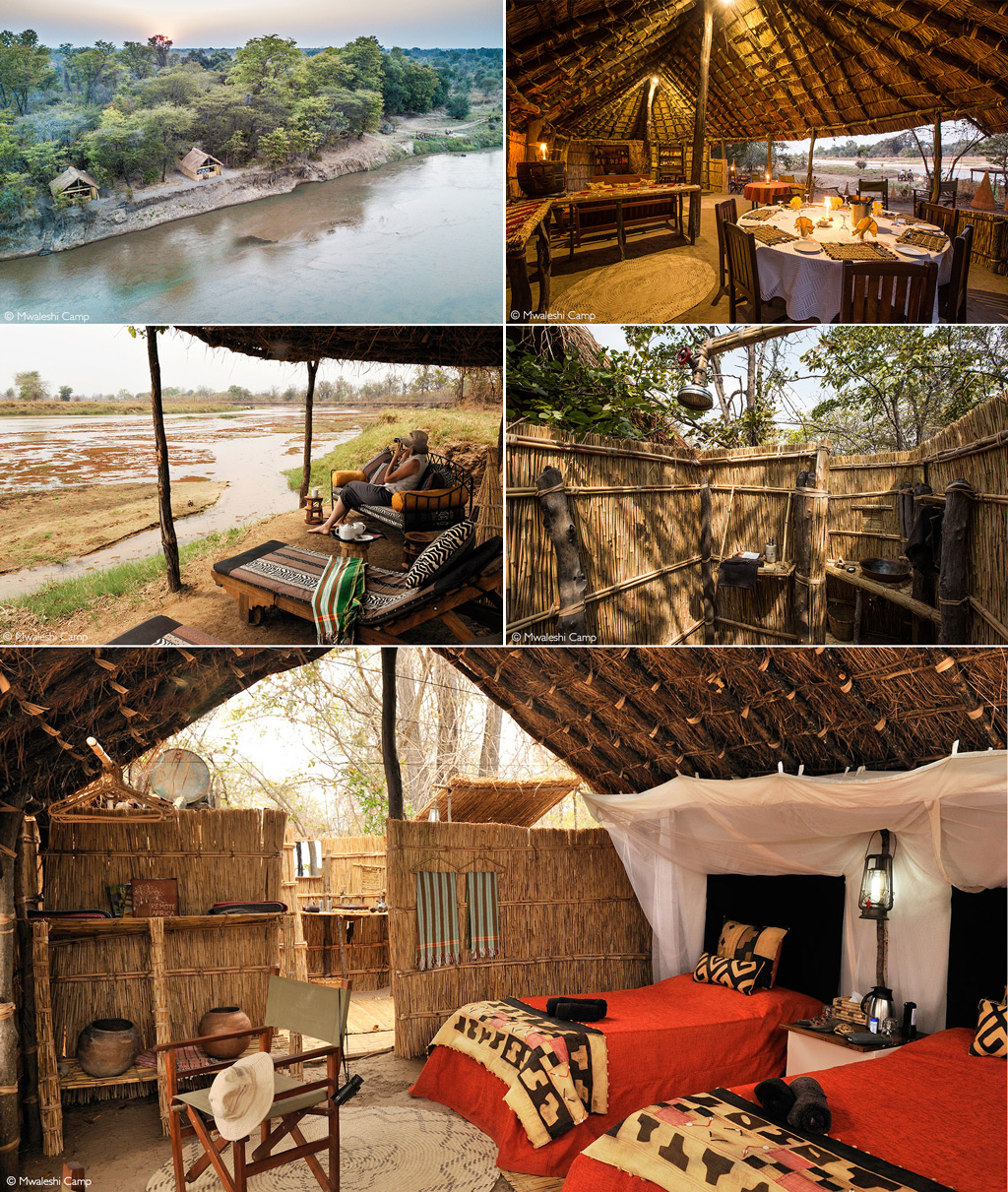

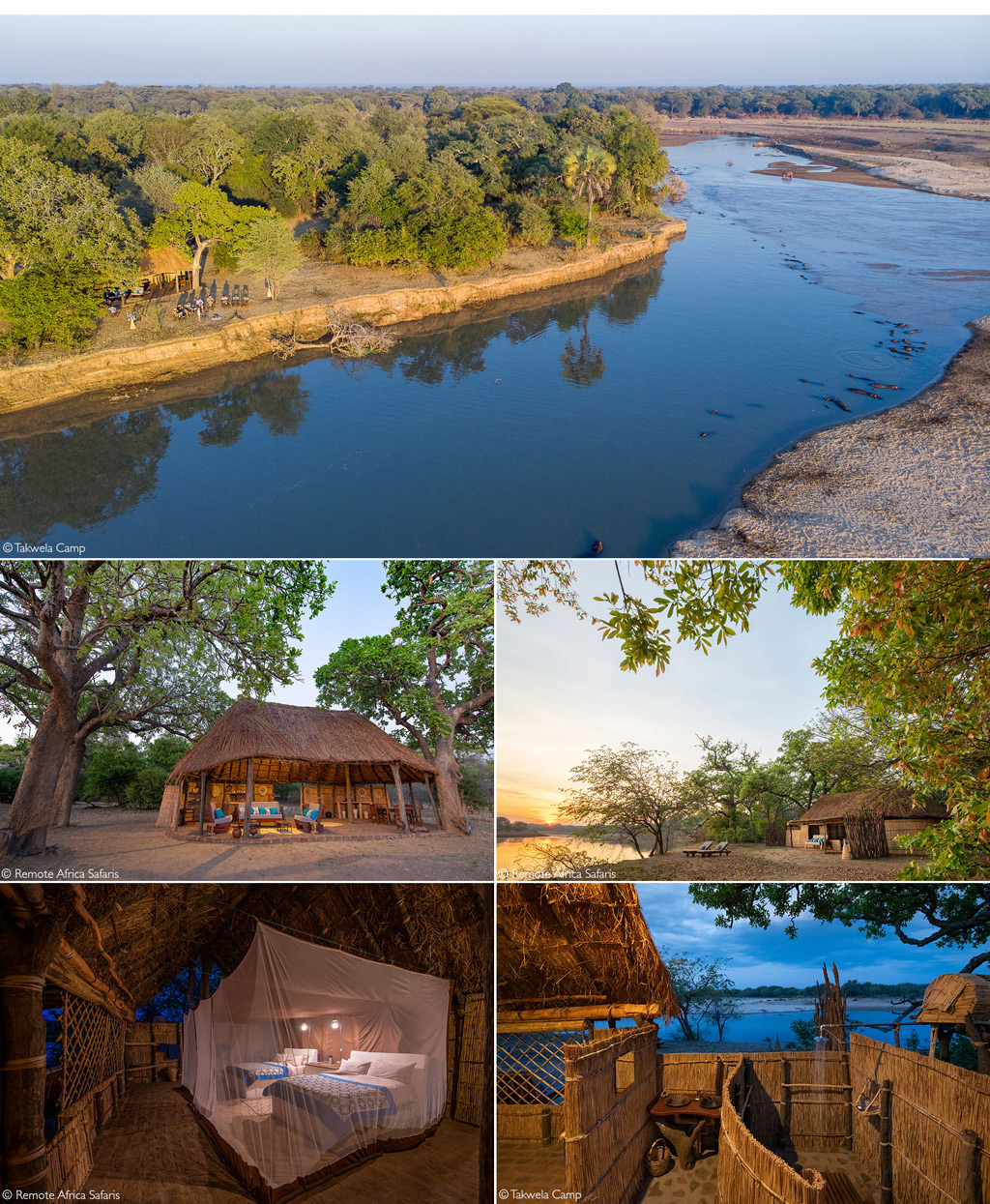

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities?

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’ Picture: Simon Espley (front) and Villiers Steyn (back) on assignment in Timbavati

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’ Picture: Simon Espley (front) and Villiers Steyn (back) on assignment in Timbavati

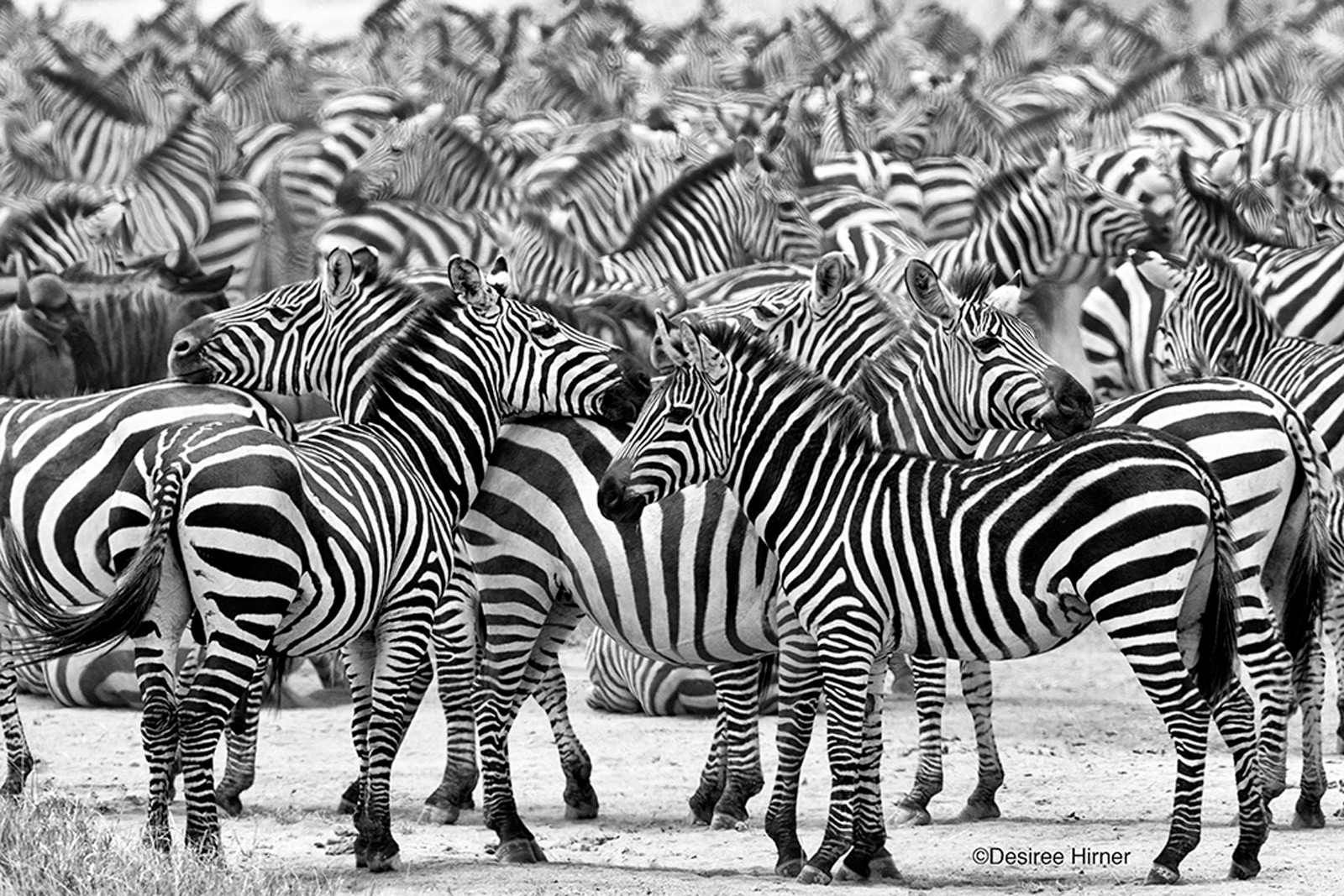

Jens Cullmann was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1969. His introduction to photography was at age 13 when he got his first camera. As a teenager, he worked with black & white film and image developing until he was able to acquire more sophisticated equipment. ‘There is a very physical aspect to my work because you need a lot of discipline and endurance to deal with some of the tough environments that come with wildlife photography.’ It was during a trip to Namibia and Botswana in 2003 that Jens’ passion for wildlife photography really ignited and he has grown in stature since then. He has won several prestigious international awards such as the 2017 Botswana Wildlife Photographer of the Year, 2018 International Photographer of the Year and most recently, he was the winner of the 2020 GDT Nature Photography of the Year 2020 (German Society for Nature Photography). Jens was a runner-up in the 2019 Africa Geographic Photographer of the Year.

Jens Cullmann was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1969. His introduction to photography was at age 13 when he got his first camera. As a teenager, he worked with black & white film and image developing until he was able to acquire more sophisticated equipment. ‘There is a very physical aspect to my work because you need a lot of discipline and endurance to deal with some of the tough environments that come with wildlife photography.’ It was during a trip to Namibia and Botswana in 2003 that Jens’ passion for wildlife photography really ignited and he has grown in stature since then. He has won several prestigious international awards such as the 2017 Botswana Wildlife Photographer of the Year, 2018 International Photographer of the Year and most recently, he was the winner of the 2020 GDT Nature Photography of the Year 2020 (German Society for Nature Photography). Jens was a runner-up in the 2019 Africa Geographic Photographer of the Year.

Marcus Westberg is an award-winning Swedish photographer and writer who focuses primarily on solution-oriented coverage of conservation topics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is a photographer for African Parks, and his work is frequently found in publications such as the New York Times, bioGraphic, Vagabond, Wanderlust and Africa Geographic. Visit his

Marcus Westberg is an award-winning Swedish photographer and writer who focuses primarily on solution-oriented coverage of conservation topics in sub-Saharan Africa. He is a photographer for African Parks, and his work is frequently found in publications such as the New York Times, bioGraphic, Vagabond, Wanderlust and Africa Geographic. Visit his

Julien Regamey’s interest and passion for the natural world began at a young age when he commenced his studies at Vivarium de Lausanne, Switzerland, under renowned herpetologist Jean Garzoni. After three years Julien went on to complete his education at Kinyonga Reptile Centre in the town of Hoedspruit near the Kruger National Park, South Africa. He then trained at the nearby Siyafunda Wildlife and Conservation, which equipped him with the skills to identify local fauna and flora, track wildlife and gain essential bush survival skills.

Julien Regamey’s interest and passion for the natural world began at a young age when he commenced his studies at Vivarium de Lausanne, Switzerland, under renowned herpetologist Jean Garzoni. After three years Julien went on to complete his education at Kinyonga Reptile Centre in the town of Hoedspruit near the Kruger National Park, South Africa. He then trained at the nearby Siyafunda Wildlife and Conservation, which equipped him with the skills to identify local fauna and flora, track wildlife and gain essential bush survival skills.

Andy Howe is a UK-based wildlife photographer who specialises in capturing the personality and character of his subjects, with a particular focus on owls and birds of prey. Andy leads small groups of photographers to India, Rwanda and Kenya. His images have been published in such publications and competitions as Bird Guides, Bird Photographer of the Year, Nature Photographer of the Year, Africa Geographic and Natures Best Awards. More recently he was appointed as a Fellow of the Society of International Nature and Wildlife Photographers and an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society.

Andy Howe is a UK-based wildlife photographer who specialises in capturing the personality and character of his subjects, with a particular focus on owls and birds of prey. Andy leads small groups of photographers to India, Rwanda and Kenya. His images have been published in such publications and competitions as Bird Guides, Bird Photographer of the Year, Nature Photographer of the Year, Africa Geographic and Natures Best Awards. More recently he was appointed as a Fellow of the Society of International Nature and Wildlife Photographers and an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society.

Charl Stols was born and raised in South Africa, where he was fortunate to visit several national parks. He began his journey in photography in 2003 while working on a cruise vessel as a resident photographer in 2003. During that time, he also met his wife, Sabine, who shares his passion for photography.

Charl Stols was born and raised in South Africa, where he was fortunate to visit several national parks. He began his journey in photography in 2003 while working on a cruise vessel as a resident photographer in 2003. During that time, he also met his wife, Sabine, who shares his passion for photography.

For Corlette Wessels photography is not merely a hobby; it’s her passion! Her father was an avid photographer and, as a child, she would always admire him behind his lens. Her love for photography grew as she got older, and she started with film and later turned to digital. By starting with film, she learned a great deal about photography, and of course learned her lessons the hard, expensive way. As her passion grew, she invested in better gear and several dedicated photographic trips with professional photographers. It was on those trips that she learned the most, from hands-on training.

For Corlette Wessels photography is not merely a hobby; it’s her passion! Her father was an avid photographer and, as a child, she would always admire him behind his lens. Her love for photography grew as she got older, and she started with film and later turned to digital. By starting with film, she learned a great deal about photography, and of course learned her lessons the hard, expensive way. As her passion grew, she invested in better gear and several dedicated photographic trips with professional photographers. It was on those trips that she learned the most, from hands-on training.

Daniel Koen was born in Durban, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa after which he moved to Alberton where he spent most of his life. His interest in nature and wildlife photography started at an early age during family trips to the Kruger National Park. He went on to study Nature Conservation at the then Pretoria Technikon and obtained a National Diploma in Nature Conservation. He currently works as a nature conservator in Gauteng. He has a deep love for the bush and dedicates as much time as possible to being in nature and honing his photographic skills. Visit his

Daniel Koen was born in Durban, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa after which he moved to Alberton where he spent most of his life. His interest in nature and wildlife photography started at an early age during family trips to the Kruger National Park. He went on to study Nature Conservation at the then Pretoria Technikon and obtained a National Diploma in Nature Conservation. He currently works as a nature conservator in Gauteng. He has a deep love for the bush and dedicates as much time as possible to being in nature and honing his photographic skills. Visit his

Daniel Wakefield is a husband, father, pastor, and amateur wildlife photographer. He became interested in wildlife, especially reptiles, at a young age. When my family and I moved to Florida five years ago, I started to explore the world of photography to help me capture and share my love of these scaly creatures. One of my goals with photography is to help people see the beauty of these often maligned and misunderstood creatures, to promote their conservation. Visit his

Daniel Wakefield is a husband, father, pastor, and amateur wildlife photographer. He became interested in wildlife, especially reptiles, at a young age. When my family and I moved to Florida five years ago, I started to explore the world of photography to help me capture and share my love of these scaly creatures. One of my goals with photography is to help people see the beauty of these often maligned and misunderstood creatures, to promote their conservation. Visit his

My passion for birding was the catalyst that prompted me into wildlife photography. For the past 24 years, I have pursued this passion with a specific focus on capturing images of wildlife in their natural environments. My travels have taken me to some of the most extraordinary places that Africa has to offer. Amongst my most memorable trips are trekking with mountain gorillas in the Virunga mountains of Rwanda; trekking with wild chimpanzees in the Mahale Mountains of Tanzania, camping on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, exploring the waterways of the Okavango Delta in Botswana, the vast Busanga Plains of Kafue in Zambia and Mana Pools in Zimbabwe. It would be difficult to choose a specific favourite, but the most profound experience was sitting amongst wild mountain gorillas in the Virungas.

My passion for birding was the catalyst that prompted me into wildlife photography. For the past 24 years, I have pursued this passion with a specific focus on capturing images of wildlife in their natural environments. My travels have taken me to some of the most extraordinary places that Africa has to offer. Amongst my most memorable trips are trekking with mountain gorillas in the Virunga mountains of Rwanda; trekking with wild chimpanzees in the Mahale Mountains of Tanzania, camping on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, exploring the waterways of the Okavango Delta in Botswana, the vast Busanga Plains of Kafue in Zambia and Mana Pools in Zimbabwe. It would be difficult to choose a specific favourite, but the most profound experience was sitting amongst wild mountain gorillas in the Virungas.

Geo Cloete is a multi-talented artist with an architectural degree from Nelson Mandela Bay University (South Africa) in 1999. The fruits of his labour have seen him complete award-winning works in architecture, jewellery, sculpture and photography.

Geo Cloete is a multi-talented artist with an architectural degree from Nelson Mandela Bay University (South Africa) in 1999. The fruits of his labour have seen him complete award-winning works in architecture, jewellery, sculpture and photography.

Kevin Dooley was born in a small mountain town in the USA where photography has been his chosen profession for almost 40 years. His passion for wildlife photography and wild places has led to many adventures, especially in Africa. He thrives on sharing Africa with others – teaching them about wildlife, trees and the history of wild Africa. Stories of adventures shared around a campfire with other travellers and photographers hold a special place in his heart. Visit his

Kevin Dooley was born in a small mountain town in the USA where photography has been his chosen profession for almost 40 years. His passion for wildlife photography and wild places has led to many adventures, especially in Africa. He thrives on sharing Africa with others – teaching them about wildlife, trees and the history of wild Africa. Stories of adventures shared around a campfire with other travellers and photographers hold a special place in his heart. Visit his

Rian van Schalkwyk is a medical doctor who lives in Windhoek, Namibia. He has a passion for nature and wildlife photography and tries to get into the bushveld at every available opportunity. He recently returned from a 9-month life-changing safari with his daughter – visiting 27 African national parks and reserves. Visit his

Rian van Schalkwyk is a medical doctor who lives in Windhoek, Namibia. He has a passion for nature and wildlife photography and tries to get into the bushveld at every available opportunity. He recently returned from a 9-month life-changing safari with his daughter – visiting 27 African national parks and reserves. Visit his

Based in the Greater Kruger of South Africa and working as photography manager for African Impact, Sam looks to introduce and showcase to other like-minded photographers the beauty that had him fall in love with Africa over twenty years ago. With this comes the added responsibility of instilling a thoughtful, ethical and conservation-based approach to how we work with the natural world. Sam’s aim is to teach photographers the importance and impact via education their work can have on the conservation of our natural biosphere. Visit his

Based in the Greater Kruger of South Africa and working as photography manager for African Impact, Sam looks to introduce and showcase to other like-minded photographers the beauty that had him fall in love with Africa over twenty years ago. With this comes the added responsibility of instilling a thoughtful, ethical and conservation-based approach to how we work with the natural world. Sam’s aim is to teach photographers the importance and impact via education their work can have on the conservation of our natural biosphere. Visit his