A tiny primate that washes its hands and feet with urine

With their large saucepan eyes, big ears and bushy tails, galagos, also known as bushbabies, are one of Africa’s most endearing creatures of the night. Often referred to in South Africa as nagapies, meaning “little night monkeys” in Afrikaans, they are regarded as one of the smallest of the prosimian primate species. Although reasonably common throughout parts of Africa, they are not easily seen due to their predominately nocturnal movements and shy demeanour.

Editorial note: NOT SUITABLE AS PETS. Galagos are social animals that live in complex family groups in the wild, and they do not survive well as solitary pets. They also have specific environmental and nutritional requirements. For these and other reasons galagos (and other primates) should not be kept as pets. The images in this story are of wild southern lesser galagos that moved into an outside patio of a house that was left empty for two years. While the house (located in a small private game reserve) is now occupied, the owners leave the galagos to their own devices.

Classification

Galagos are members of the taxon Strepsirrhini, which is one of the two suborders of primates, and one that also includes the prosimians known commonly as lemurs, lorises, pottos, and aye-ayes.

Galagos are only found on the African continent and are currently grouped into three genera, with the two former members of the now-defunct genus Galagoides returned to their original genus Galago. According to the IUCN, there are currently 18 recognised species.

• Genus Otolemur: thick-tailed, or greater galagos (2 species)

• Genus Euoticus: needle-clawed galagos (2 species)

• Genus Galago: lesser galagos (14 species)

Galagos are a diverse group, and the taxonomy of the genus is frequently disputed and revised in literature due to the increasing use of genetics, as well as new behavioural techniques for studying nocturnal primates.

The three most frequently encountered species are the southern lesser galago (Galago moholi), northern lesser galago (Galago senegalensis), and the thick-tailed greater galago (Otolemur crassicaudatus).

In this feature, we will be looking only at the southern lesser galago.

CONSERVATION STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION

The southern lesser galago is listed as ‘Least Concerned’. This is a common and widespread species, and the IUCN Red List indicates they have a stable population without significant threats.

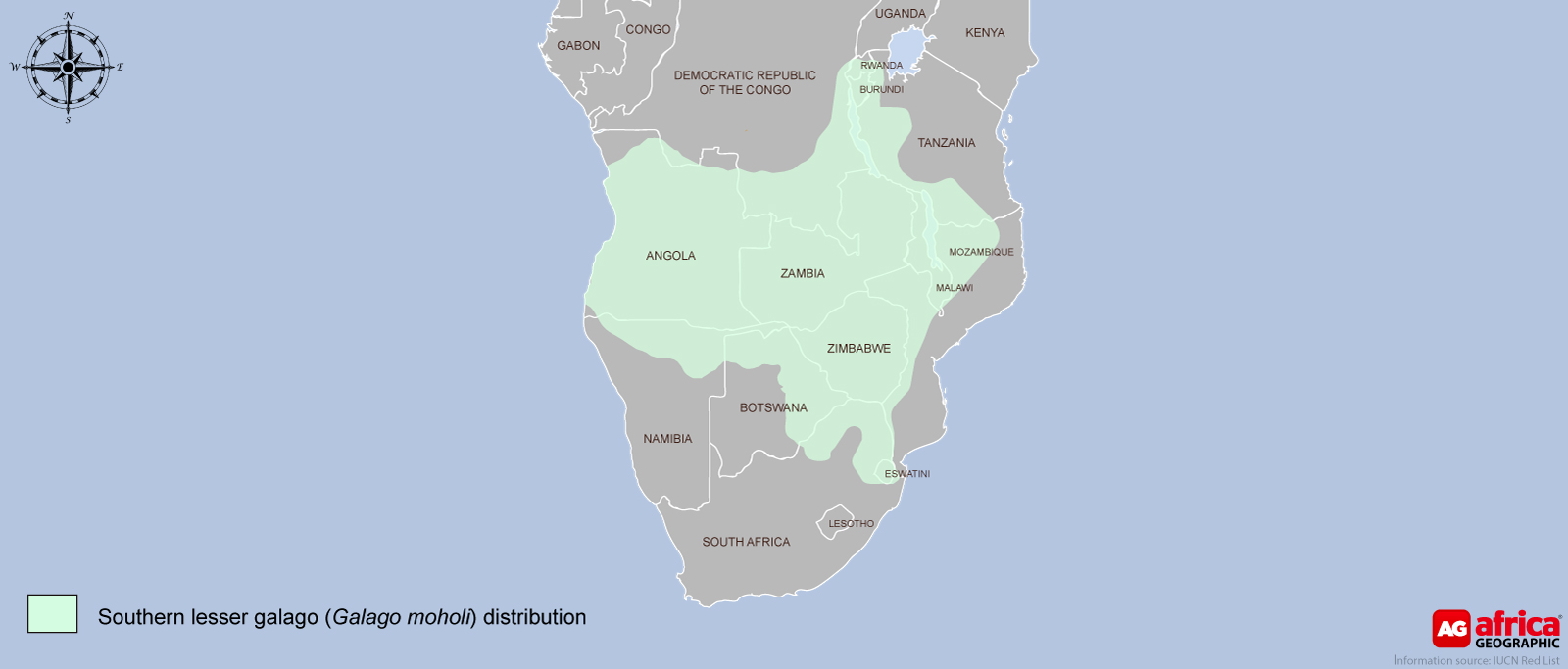

This galago is widely distributed within the southern African region, ranging from northern Namibia and Angola, eastwards through the southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, Zimbabwe and north Botswana to western Tanzania, Malawi, eastern Mozambique and the northern and northeastern parts of South Africa. The northern limits of the distribution range of this species are not well defined, although the range (shown on the map below) includes Rwanda and Burundi, where their presence requires confirmation.

The southern lesser galago is recognised as one species with two subspecies: Galago m. moholi in the eastern part of the range, and G. m. bradfieldi in the northern reaches.

MORE ABOUT…

Southern lesser galagos inhabit semi-arid woodlands, savanna woodlands, gallery forests, and the edges of wooded areas. They often make their homes in the hollows of trees – mainly in acacia and mopanes trees – that provide a safe den for resting and breeding. Occasionally they will construct nests in the forks of branches, but they much prefer to use natural holes. Steering on the side of caution when it comes to wildfires, galagos like to choose trees with very little grass around them. Man-made beehives are another favourite nesting site.

Southern lesser galagos live in small social groups. They can be found sleeping in groups of 2-7 during the day. These groups are typically comprised of a female and several of her young. The males sleep separately from the females. At night the groups separate to forage independently, or in very loose associations, with each spending approximately 70% of their waking time alone. By dawn, they regroup and return to their nesting site. However, when temperatures are extremely cold galagos shorten their foraging activities by several hours and return to sleeping sites early. In such circumstances, they can be active during the day.

Galagos are territorial, with the size of the range dependent on food availability. Aggressive territorial behaviour from dominant males may be seen at range borders. Female offspring may remain with the mother until maturity, sharing her home range and raising offspring together with her, while male offspring disperse out of the maternal range at the age of about nine months. After moving, young males are non-territorial and range widely over the territories of older males and females.

Being one of the smallest primates, the southern lesser galago is about the size of a squirrel, with a head and body length of 14-17 cm and the tail an average of 11-28 cm. Males are larger and weigh between 160-255 g, while the females are approximately 142-229 g.

The coat of galagos varies between brownish-grey and a light brown hue, with their limbs often a creamy yellow colour. And fitting for a nocturnal animal, galagos also sport a dark ring around each eye.

Their adorable features of large eyes and ears do serve essential functions. Their huge, amber-coloured eyes enable them to see well in the dark while their fragile, bat-like ears allow them to track their prey at night. Their ears can be moved independently and are thought to be among the largest ears, proportionate to body size, of all primates. When they jump through any rough terrain, like thorn bushes, they fold their ears flat against their heads to protect them – thanks to four transverse ridges that allow the tips to be bent down almost to the base.

Unique nails on their hands and feet are shaped similar to our own, except for their second toe which is modified specially to be a grooming claw. This claw is used by the galago to groom the head area, clean the ears and spruce up the neck fur.

DIET

Galagos have a diet that varies from season to season. They are primarily insectivorous and gummivorous, though fruit and other vegetation make up a small percentage of their diet. They are ferocious little hunters that adore arthropods – including butterflies, moths and beetles – and can snatch them from the air with remarkable accuracy.

Acacia gums play a significant role in the diet and are a particular favourite for galagos, especially during the winter months or in times when there is reduced insect availability. The southern lesser galago has physical adaptations for eating plant gums, including a rough, narrow tongue capable of harvesting gums from insect holes and tree crevices, well-developed tooth-combs (the incisors on the lower front jaw), and special bacteria in their stomachs that can break down and digest gum. They appear to have co-evolved with gum-producing trees, and they help to control insect numbers.

COMMUNICATION

Southern lesser galagos communicate chiefly using odour and sound, although they have excellent night vision and appear to recognise one another from a distance.

They have an extensive vocal repertoire comprising up to 25 different calls. This includes, but not limited to, barks, hoots, clucks, yaps, whistles, chattering, wails, croaks and squealing sounds. Reversing a shrill whistle acts as an alert for danger.

BEHAVIOUR

A galago’s tail is longer than the length of its head and body and serves to propel it through the air. Also, they have long, well-developed hind legs. This means that in just a few leaps it can easily clear 9 metres, in seconds. Being an expert leaper is what helps the galago catch its prey and escape predators. When it’s not leaping the galago travels by kangaroo-style hops or by simply running or walking on four legs.

Galagos engage in ‘urine washing’. This is where they coat the hands and feet with urine which is transferred to the fur of social group members during bouts of reciprocal grooming. Urine washing also dampens the hands and feet and may improve grip while moving about. While traversing through vegetation, they will often leave a trail of urine-scented footprints which allows them to know which branches are safe to jump on when they move to and from their nest. Male galagos also use urine-marking as a way to mark their territories, and will sometimes become hostile toward any other males who invade their space.

REPRODUCTION

Females give birth during two birth seasons, between January and February and between October and November. When the female is in heat, she plays hard to get and will rebuff the males’ first couple of attempts at courtship. When she finally does give in, she will mate with up to six different males.

After a 121 to 124-day gestation period, females give birth to 1-3 offspring weighing approximately 10 grams. They are born with their eyes open and are furred. They stay in the nest for the first 10 to 11 days. After that, the mother will carry the babies around by the scruff of their necks for the first 50 days, but she will leave them clinging to tree forks or tangles of vegetation (known as ‘parking’) while she moves about foraging. Offspring are weaned at about ten weeks of age. It is common for the young males to move off when reaching sexual maturity at the age of about nine months, while the females tend to stay in their natal group. The males do not directly participate in caring for the offspring.

In the wild galagos tend to live no longer than three to four years, but in captivity, they can live up to 14 years.

PREDATORS AND CONSERVATION THREATS

Predators of the southern lesser galago include eagles, owls, genets, mongoose, civets, African wildcats and large snakes. They protect themselves from predation by nesting in tree holes and being active at night, and avoid predation via warning calls among group members and agile leaping. Some animals enter into periods of seasonal torpor (heterothermy) – long periods of inactivity, with reduced body temperature and metabolism as a survival mechanism during times of low food availability –. Still, research reveals that galagos do not do so. This is probably to maximise reproductive success in a high predator environment. Humans also consume galagos as bushmeat, used for traditional medicine purposes and captured for the illegal pet market.

The biggest threat to the galago population is human-induced habitat loss and degradation. As urban development encroaches more and more into the bush, the habitat of the galagos is destroyed. While galagos, in general, are quite widespread, some have more restricted ranges and are more susceptible to the effects of habitat loss and degradation.

One such example is in the suburb of Fourways in Johannesburg, South Africa, where land developers wish to flatten a small greenbelt corridor for further housing development. This habitat is home to what some consider the most southerly population of southern lesser galagos, and residents have been fighting to keep the developers at bay through their campaign Save the Fourways Bushbabies and calling for the public to sign their online petition.

FINAL WORD

Southern lesser galagos are a charismatic species, important in ways that most humans do not understand or value. Ecologically, as insectivores, they help to control populations of insects and, as frugivores, they help in the dispersal of seeds. They are also a valuable source of protein for creatures higher up the food chain – mammals, birds and reptiles. One thing that most humans would appreciate about galagos is the cuteness factor, which these tiny primates have in spades. ![]()

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Noelle Oosthuizen

Growing up watching Beverly and Derek Joubert’s documentaries and idolising Jane Goodall, Noelle has always dreamed of living in the bush. For now, she writes about her bush adventures from her home in Cape Town, South Africa. She has a particular soft spot for chacma baboons, and she advocates for these charming primates every chance she gets. By far her favourite adventure has been being a foster mom to an orphan baby baboon.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()