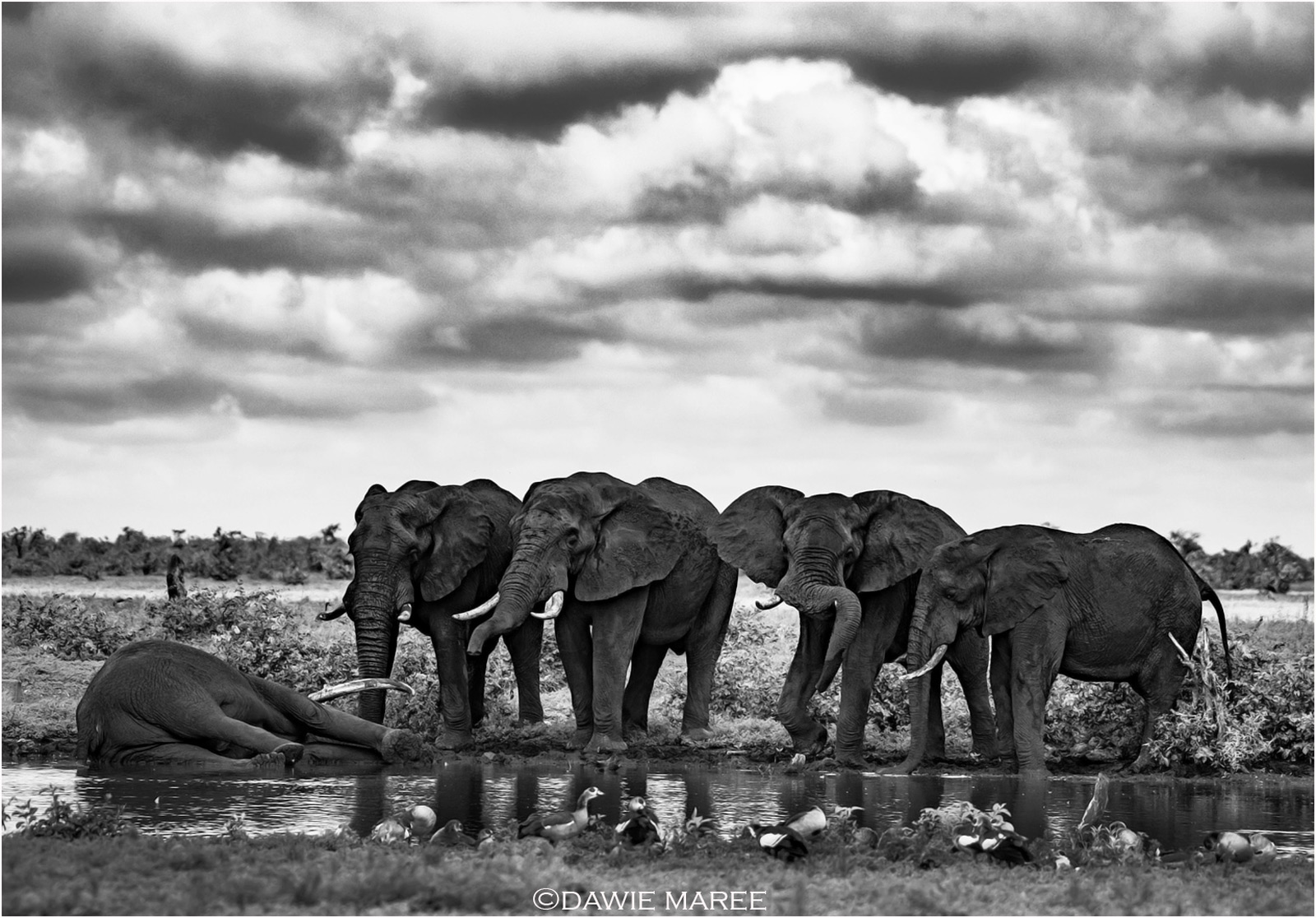

‘Elephant down!’ came the raspy bark over the vehicle radio, and the crew leapt into action as we all converged on the fallen behemoth. In the dust storm kicked up by the hovering helicopter, wildlife vet Dr Joel Alves jumped from the helicopter skids like Tom Cruise – a freefall of some three meters! I kid you not; the man who shot the dart from the helicopter was first on the scene – all in a day’s work.

Within minutes Hendrik, the sizeable male elephant, was being collared, measured and sampled by teams of experienced professionals accompanied by willing helpers. Each had a list of tasks, and they set about accomplishing those with ruthless efficiency, awash with dollops of excitement, wonder and curiosity.

? The scramble to get to Hendrik, the bull elephant, as he went down

There are some fantastic mutually beneficial goings-on here:

1. An elephant collar is being replaced, to enable ongoing research into his movements;

2. Tourists enjoy a unique, hands-on safari experience that goes way beyond game drives and sundowner drinks;

3. A donor gets to enjoy experiencing his donation being put to work.

‘Would you like to stick your arm up the elephant’s rectum to extract a dung sample?’

The question hung in the air as I felt the need to study my mobile phone screen intently. ‘Um, no thanks, got work to do’ I muttered as I shuffled away. Seconds later, this rite of passage (who knew?) was grabbed by another member of the group who donned surgical gloves and got stuck in.

As I worked the scene, shooting images on my iPhone and making mental notes for this story, I took the time to stand back and observe. This visceral experience is an immensely primal one, and certainly emotional. I wish more people could experience this intense scene firsthand – it’s an ideal family safari activity. Up close to the helpless slumbering giant, I ran my fingers over his thick, coarse skin and felt his belly gently rise and fall as he explosively snore-breathed through his trunk, a stick propping it open at the end so that he could breathe. With all of this going on, I pondered the ‘why’ of this process.

? The crew gets to work collaring, measuring and sampling

WHY COLLAR ELEPHANTS?

Elephants are a big deal for Africa. Crucial ecosystem engineers, they benefit biodiversity in so many ways that ecosystems deteriorate when elephants are removed. And they are massive tourism drawcards, generating hard currency for cash-strapped economies. BUT, it’s also true that confining too many elephants into the diminishing available elephant rangelands can impact negatively on trees and on humans living in those areas. The more we understand about how elephants utilize ecosystems, the better we can deal with the increasing pressures resulting from too many humans. And so, Elephants Alive collars and monitors elephants in the Greater Kruger area and further afield. Their research is used to fine-tune elephant management in the region. On this day they collared their 170th elephant!

? Hendrik recovers from the anaesthetic

MINING AND ELEPHANTS

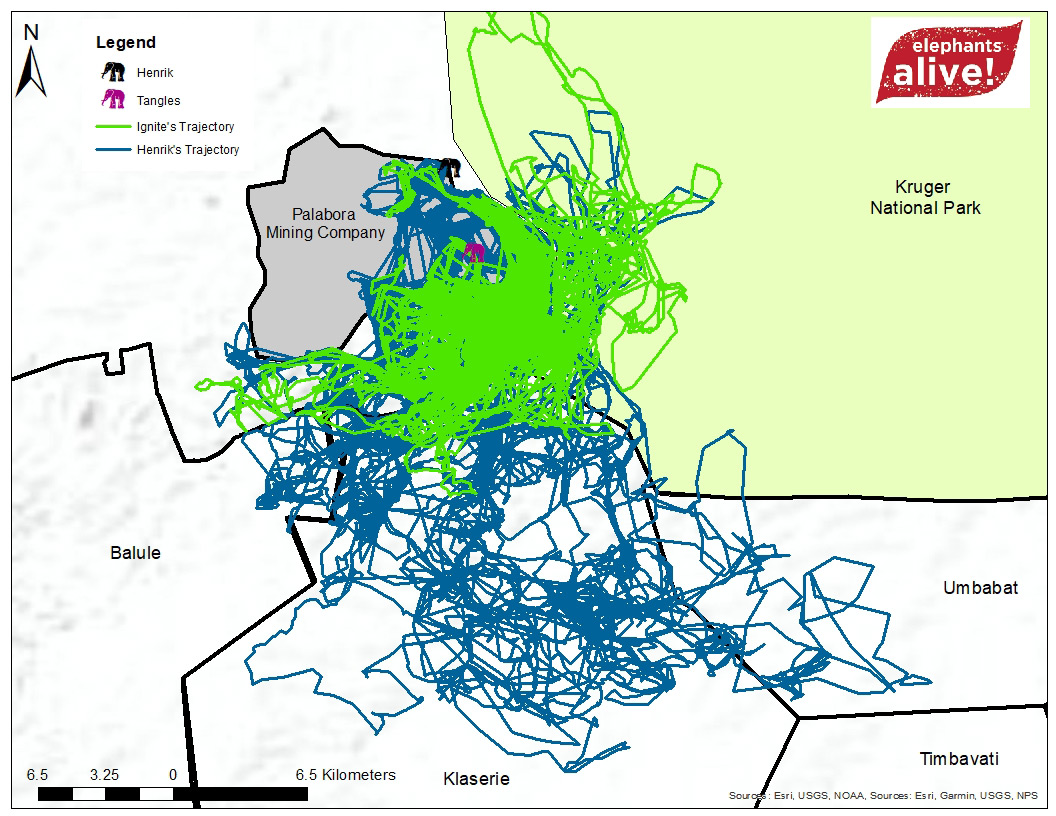

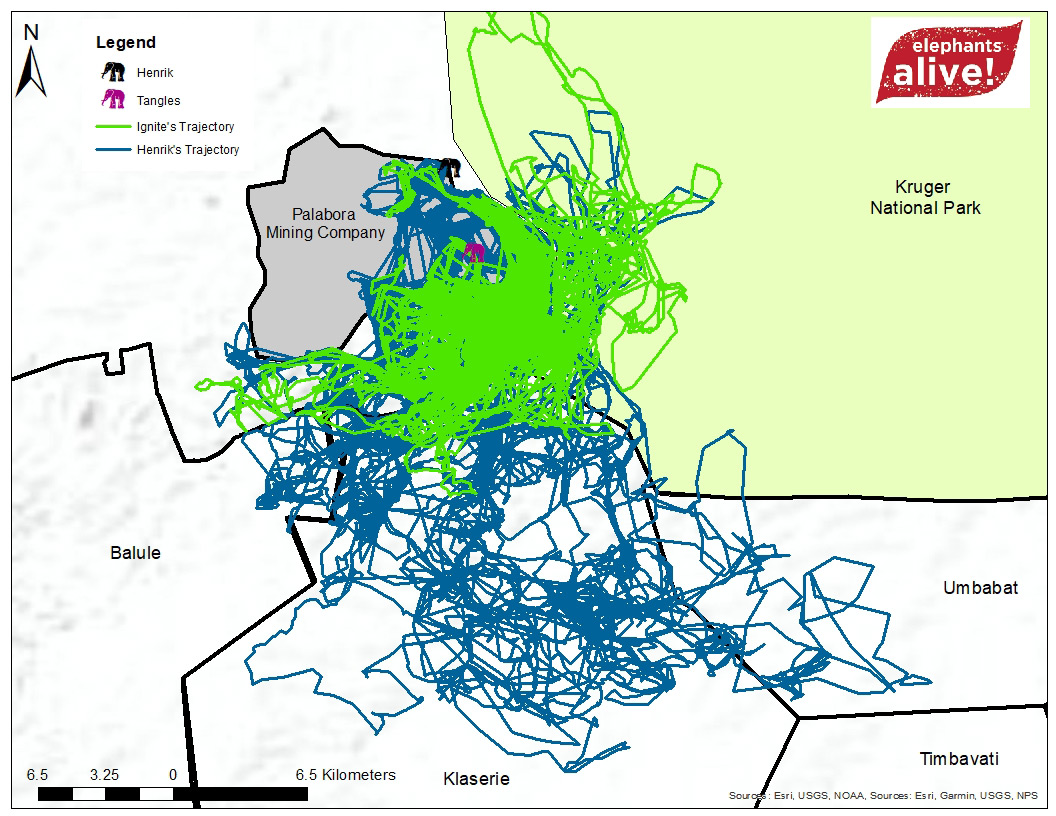

In this instance, we were collaring elephants in the grounds of the Palabora Mining Company (PMC) bordering the town of Phalaborwa, an active copper mine and a significant source of employment in the region. PMC has a private game reserve that shares unfenced borders with the Greater Kruger and Kruger National Park, and elephants and other creatures, great and small, wander in and out of the mine area freely. In fact, says Dr Michelle Henley of Elephants Alive, elephants congregate in significant numbers on this property because of the higher concentration of minerals such as phosphorous compared to the neighbouring areas. Valuable nutrients are continually being brought to the surface during the mining process, and these are present in the forage growing in the area, as well as the water sources. This nutrient-rich area allows elephants to have smaller ranges here than in neighbouring areas.

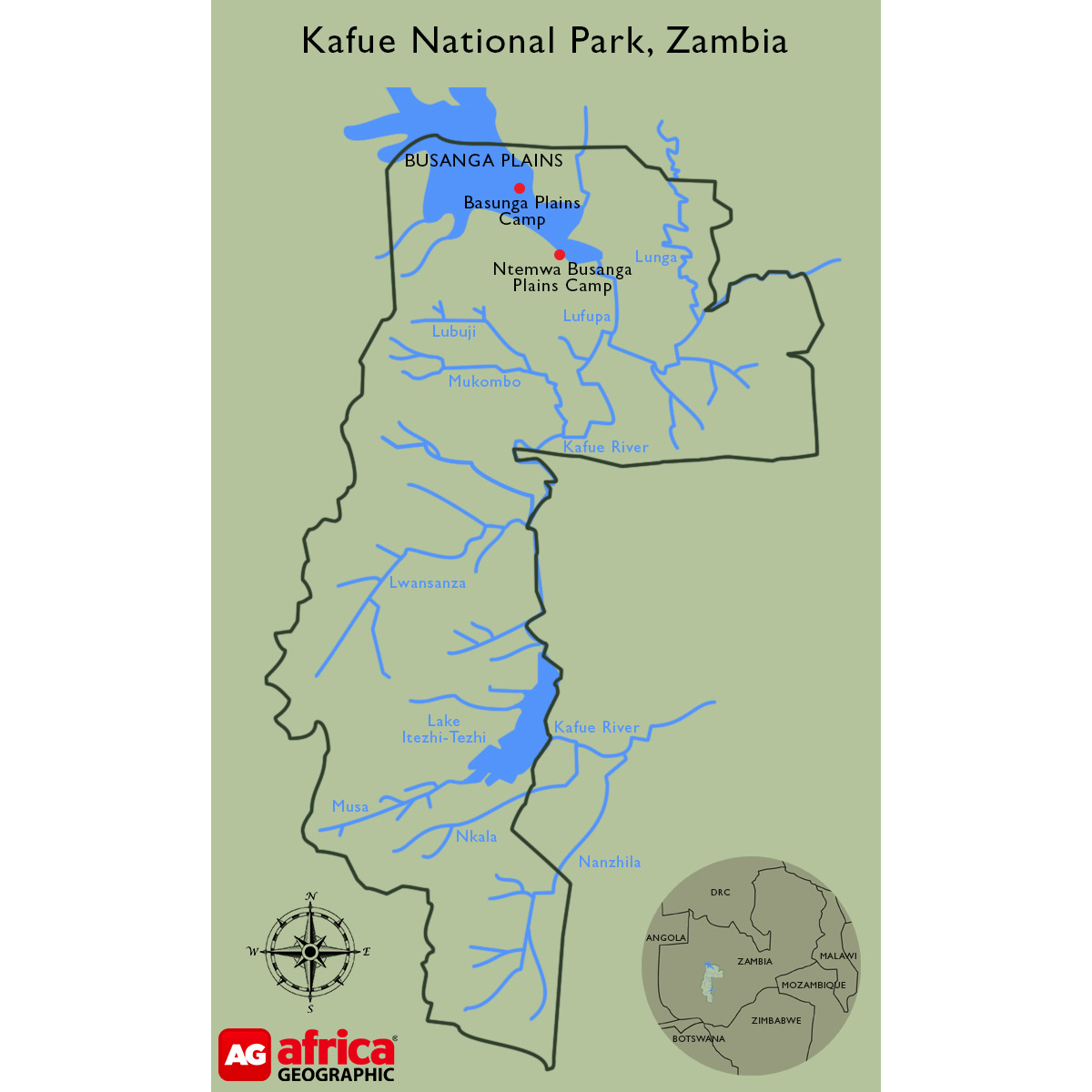

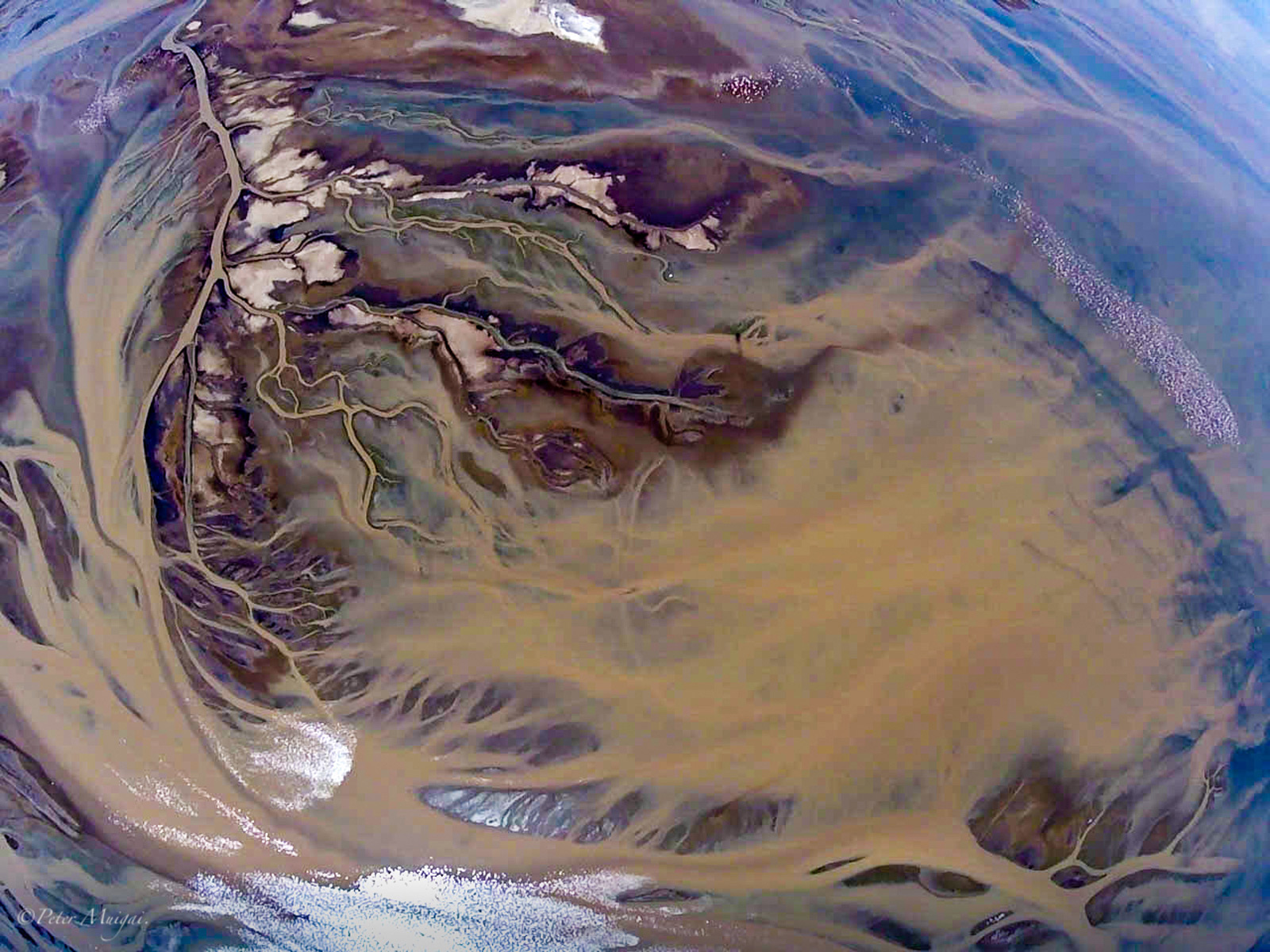

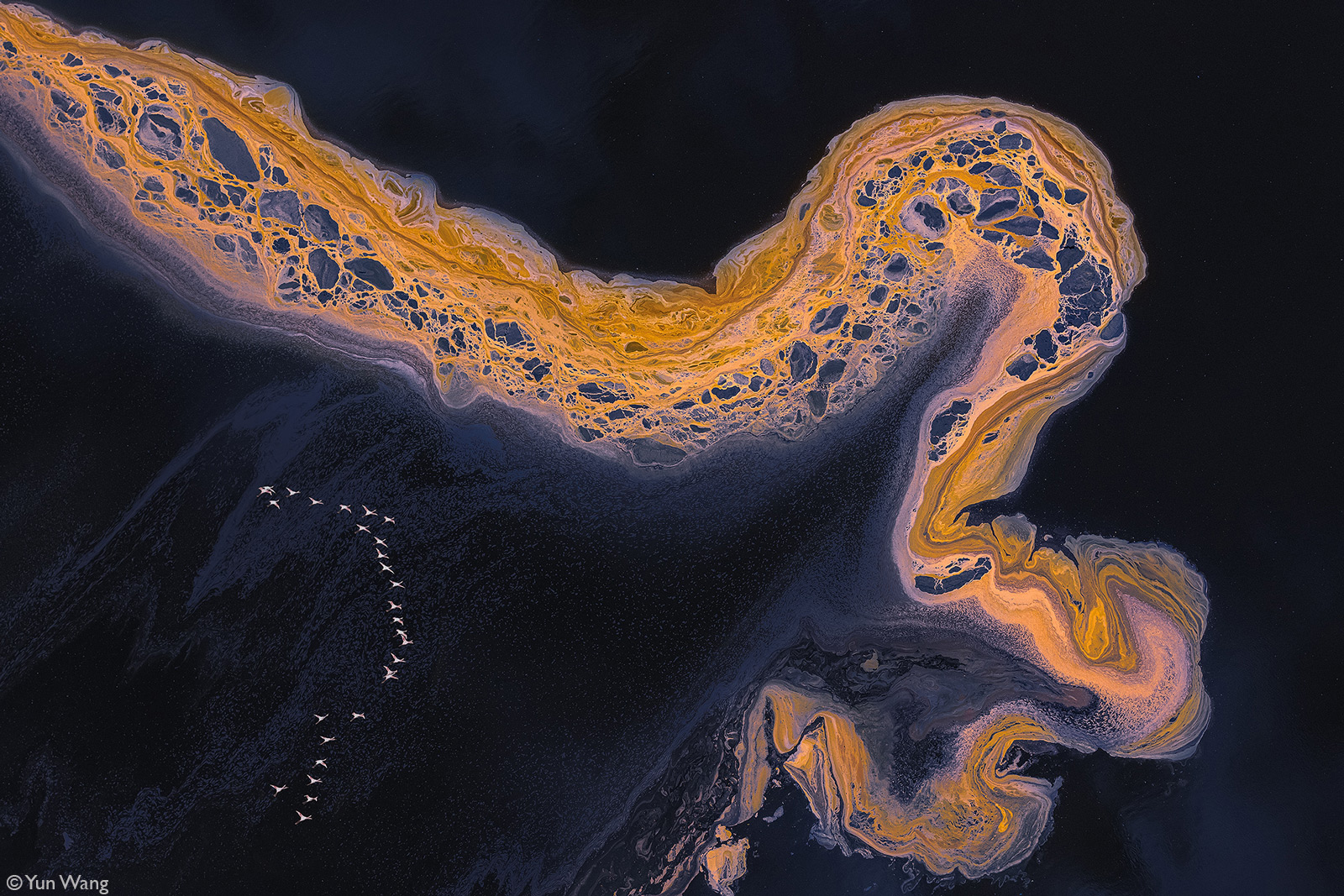

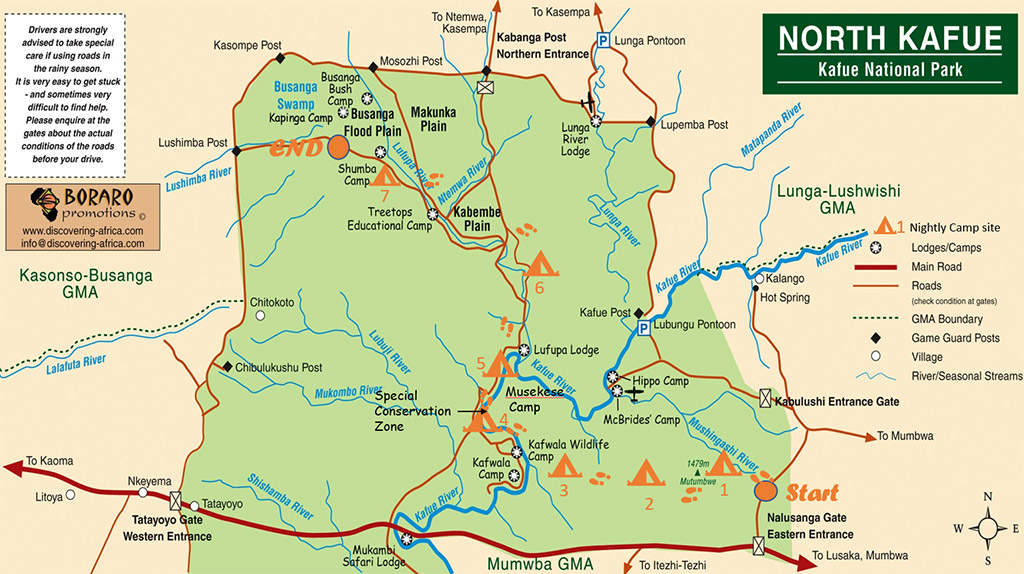

? The wanderings of elephants Hendrik and Ignite plus the two collaring sites for Hendrik (recollaring) and Tangles (first collar). Compiled by Anka Bedetti of Elephants Alive.

TWO ELEPHANTS AND THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY

Hendrik’s recovery from the opioid & morphine-based anaesthetic was rapid. Moments after the reversal was administered, he rocked to his feet before casting us a dismissive look and ambling off, seemingly unperturbed. We also collared a cow that day, one with a small calf in tow. The helicopter pilot skillfully split the herd and shepherded the cow to an open area before she went down. We watched from a nearby hill and sped to the scene when the call came through. This time the collaring and sampling was completed sooner, because of her having a young calf. I watched with fascination as Michelle milked the cow, squirting a small sample into a test-tube, and as fellow Elephants Alive crew member Ronny Makukule clipped those huge elephant toenails and pulled out a few tail hairs. This cow was named Tangles, after the Tanglewood Foundation, run by retired businessman Peter Eastwood, who donated both collars for that day.

? Bird’s-eye view of the scene as Hendrik is collared

If things had run as they were planned, the second elephant collaring would have been of the celebrated elephant cow Ignite (click here to see her being collared in this 2016 video), but she dropped her collar days before and disappeared off the radar. The Elephants Alive crew have been gleaning valuable data from Ignite’s movements for four years, and losing her was a setback for the project.

I spoke to Carla Geyser of Blue Sky Society Trust, who sponsored Ignite’s collar in 2016 and was here with some of her 2016 crew, to see Ignite recollared. She was stoic about the loss of the collar, saying “This is Africa, and these are wild elephants – and that unpredictability is why we love what we do. Ignite has gone off-radar for a while, and hopefully, she will be recollared sometime in the future and be ‘re-ignited’? ” Since Ignite’s collaring in 2016 Carla has led various expeditions spanning Southern and East Africa with like-minded conservation warriors. She continued: “ In a world filled with so much doom and gloom, it’s so nice to be able to focus on something good for a change. Mama Africa is a special place, and elephants embody everything good about Africa and family. The way the matriarch leads her herd with great strength and confidence is inspiring. They are empathetic, compassionate and supportive creatures who grieve for their dead and rally to protect each other; something that humans could learn from. The bond between sisters, mothers and calves is magnificent to watch.”

? Hendrik’s foot

SCIENCE DRIVES THE NEED

The most crucial point to understand about elephant collaring exercises is that they are driven by science and the need for data. Collarings are never performed on request from donors or tourists. Entities such as Elephants Alive try to cover their costs by reaching out to donors and to cause-based entities such as Blue Sky Society Trust to provide a handful of paying guests, but those donors and guests do not influence the timing or process.

SPONSORING AN ELEPHANT COLLAR

Sponsoring an elephant collar is about covering the costs incurred by the research-based entity, in this case, Elephants Alive. Current costs are US$5,000 for the collar plus R35,000 (approx US$2,000 at today’s exchange rate) for local costs such as vets and the helicopter.

? Collar sponsor Peter Eastwood reverses the anaesthetic administered to Hendrik, supervised by vet Joel Alves

ATTENDING AN ELEPHANT COLLARING

Attending an elephant collaring is without question a top-drawer experience. BUT …

Elephant collaring cannot ever be a mainstream tourism experience – there are too few bona fide elephant research and monitoring projects in existence. And, of paramount importance, the logistical and legal requirements and the necessity for highly experienced crew translate into this being a waiting-list experience for tourists. Cautionary: With so many pop-up wildlife encounters on the tourism scene these days (think lion cub petting and elephant-back riding), you should select your wildlife encounters carefully.

If you wish to attend an elephant collaring exercise, my advice is that you contact an ethical, cause-based entity such as the Blue Sky Society Trust. Carla Geyser is in constant touch with research-based entities across Africa and is well-placed to give the best advice.

? Pilot Gerry McDonald and Elephants Alive crew member Ronny Makukule

SPECIAL MENTIONS

In addition to the crews from Elephants Alive and Blue Sky Society Trust, the following played a leading role in this elephant collaring day:

• Permits & logistics. – Tertius Hofmeyr, Johann McDonald, Mark Surmon and Sasha Muller from Palaborwa Mining Company

• Provincial permits – Dirk de Klerk of Limpopo Department: Economic Development, Environment and Tourism (LEDET)

• Neighbour permissions – Kruger National Park, Foskor, Phalaborwa Military base & Klaserie Private Nature Reserve

• Vets – Dr Joel Alves, Dr Hamish Currie and Hayley Hooper (intern)

• Helicopter pilot – Gerry McDonald

• Sponsor – Peter Eastwood from Tanglewood

• Photos/videos – Thorge Heuer and Kevin MacLaughlin

• Video compilation – Aïda Ettayeb (Douda Aïda)

• Game viewer vehicle – Derik Scorer from Nissan Hoedspruit

WATCH THIS fantastic video of the elephant collaring day described above (2.13 minutes)

? The collaring crew with Tangles, who was collared for the first time.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, SIMON ESPLEY

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’.

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’.

![]()

Jens Cullman is a German nature

Jens Cullman is a German nature

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’.

Simon Espley is an African of the digital tribe, a chartered accountant and CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are in search of wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit with his wife Lizz and two Jack Russells, and when not travelling or working, he will be on his mountain bike somewhere out there. His motto is ‘Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change.’.