Africa’s sensational destinations each come with their own magnetism. But no matter where you happen to find yourself, a magnificent swimming pool is guaranteed to add an extra element of magic.

Read on to discover our favourite pools in Africa.

Want to go discover the best swimming pools while on an African safari? We have ready-made safaris to choose from, or let us build one just for you.

Want to go discover the best swimming pools while on an African safari? We have ready-made safaris to choose from, or let us build one just for you.

Best for ocean views

What can be better than gazing out over the big blue, cocktail in hand, while floating in temperate, calm waters? Look no further to find the best oceanside pools.

Azulik Lodge, Vilanculos, Mozambique: Perched atop a massive dune in a wildlife sanctuary is the tropical paradise of Azulik Lodge. As views from infinity pools go, this one across this corner of the Indian Ocean is hard to beat. Grab an R&R (Tipo Tinto rum and raspberry) or some fruit kebabs, and let the peace of paradise wash over you.

Canelands Beach Club & Spa, Salt Rock, South Africa: With 180˚ views of the ocean, the long pool at Canelands Beach Club & Spa is the perfect spot to watch for the fins of passing dolphins surfing the waves.

Tintswalo Atlantic, Cape Town, South Africa: Situated on the ocean’s edge, below Chapman’s Peak and offering spectacular views of one of the most beautiful urban/natural settings in the world, the view from the Tintswalo Atlantic pool is simply unbeatable.

Best for bush views

You can never get too much of the bush. But after a long day out on safari, soaking it all up while washing off the day and taking in the surroundings can be just the decompression you need.

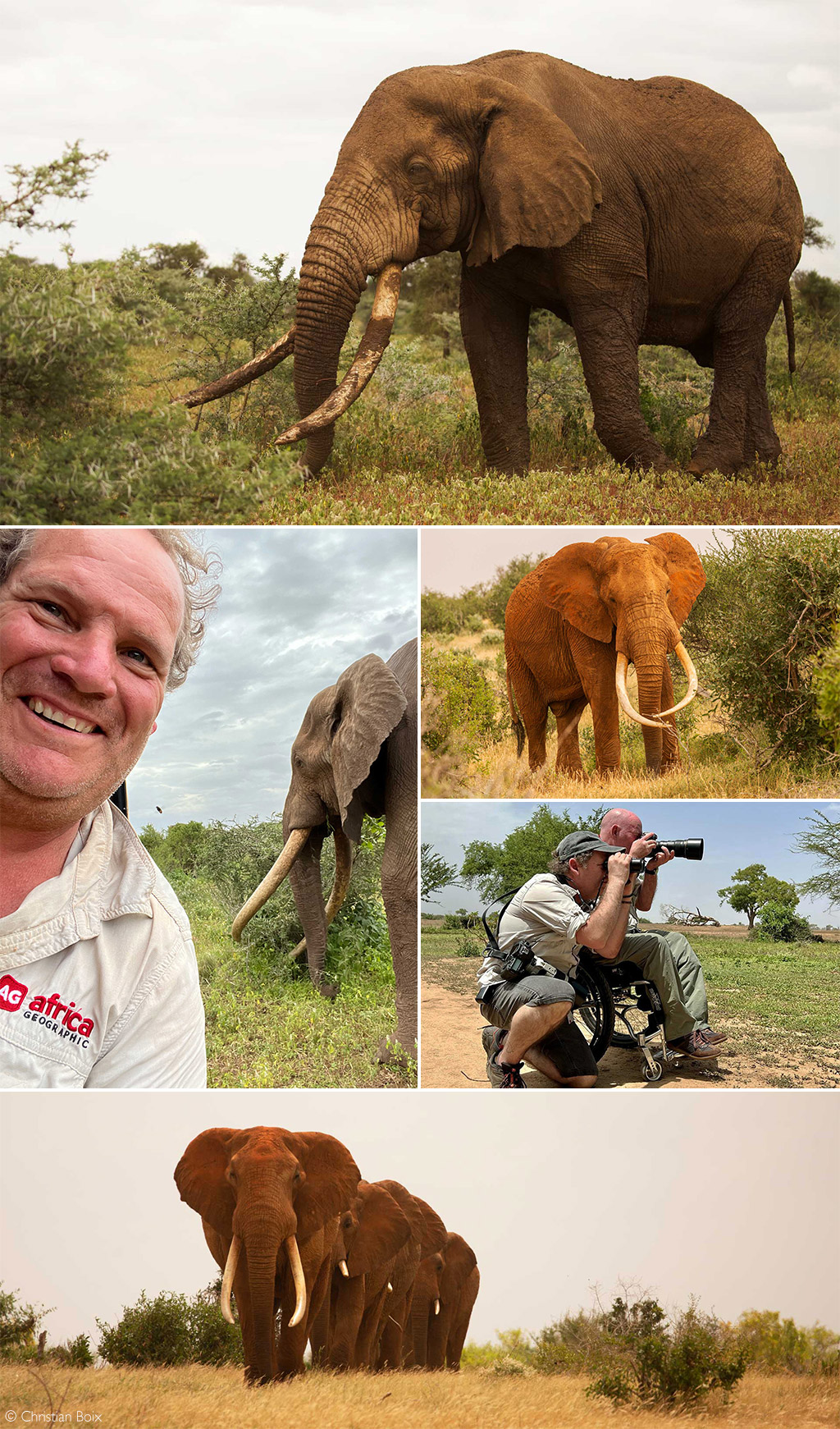

Ol Donyo Lodge, Chyulu Hills, Kenya: 1.4 million years ago, ancient tectonic forces began to propel lava to the surface in a series of volcanic eruptions that created the Chyulu Hills. Today, the swimming pool at Old Donyo Lodges looks out across this magnificent ancient scenery where some of the last great tuskers still roam.

Settlers Drift, Kariega Game Reserve, South Africa: Tucked into a steep, densely vegetated slope in a remote corner of Kariega Game Reserve, Settlers Drift offers spectacular views over the Bushman’s River, and the pool is the best spot to take it all in.

Khaya Ndlovu Manor House, Hoedspruit, South Africa: The infinity pool at Khaya Ndlovu Manor House looks out across to the Limpopo Drakensberg Mountains and over the miles of bushveld between. On a blazing hot Lowveld day, take refuge in the pool and watch arguably one of the most beautiful sunsets in the world.

Amalinda Lodge, Matobo Hills, Zimbabwe: Matobo Hills is Zimbabwe’s oldest national park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Like the rest of Amalinda Lodge, the swimming pool has been incorporated into a granite outcrop to look out across a wilderness of wildlife and history.

Kubu Kubu Tented Lodge, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania: In the heart of Serengeti National Park, the pool at Kubu Kubu Tented Lodge overlooks the vast sweeping plains of the “place where the land runs forever”. Close to the Maasai kopjes, the Museum of Olduvai Gorge, Seronera and the Grumeti River, visitors here will have no shortage of options for adventuring. But a day spent at the pool overlooking the bush is high up on the bucket list for memorable moments in the Serengeti.

Best for sighting wildlife

Don’t feel like being out on safari for the day? Satiate your FOMO by having your own sightings right in camp.

Mihingo Lodge, near Lake Mburo National Park, Uganda: Perched high atop the granite boulders of a kopje, the Mihingo Lodge infinity pool provides a magnificent vantage point for spotting wildlife in the savannah valley below.

Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge, Gonarezhou National Park, Zimbabwe: On the northern border of Gonarezhou National Park, one of the last true pristine wilderness areas in Africa, Chilo Gorge Safari Lodge looks out across the vast expanse of the Save River. Sip a cocktail in the cool waters while watching animals moving in for a drink below.

Saruni Samburu, near Samburu National Reserve, Kenya: Guests of Saruni Samburu can take their pick between two different swimming pools that overlook a waterhole. Escape the arid heat and watch as some of Samburu’s fascinating wildlife wanders through! Check out our Samburu special offer here.

The Manor House, Samara Karoo Reserve, Great Karoo, South Africa: Samara Karoo Reserve is a pioneering conservation journey to regenerate South Africa’s semi-arid Great Karoo region through rewilding and responsible tourism. The mountain landscape unfolds over a 21-metre infinity pool, descending to a waterhole frequently visited by wildlife.

Best oases in the African heat

Africa’s sweltering sun and desert destinations don’t need to leave you feeling flustered. Soothe away the scorch in the cool welcoming waters.

Pel’s Post, Makuleke Contractual Park, Kruger National Park: The magnificent eco-lux property Pel’s Post offers views over the Luvuvhu River. It is an exclusive-use property, so the pool is shared only with family and friends. Temperatures in the magical Makuleke Contractual Park regularly exceed 40˚C, so a refreshing dip, with the sound of elephants not far off, is essential.

Chitwa Suite, Sabi Sands Game Reserve, South Africa: Picture this: you’re awoken at the crack of dawn with freshly brewed coffee, treated to a morning of leopard sightings and returned to the lodge for a sumptuous breakfast. The remaining hours of the day stretch ahead, begging to be filled with something relaxing yet extraordinary. As the sun bakes overhead, this is the perfect time to escape into the azure waters of your private swimming pool.

Kwessi Dunes Lodge, NamibRand Nature Reserve, Namibia: In the vast desert wilderness, the pool at Kwessi Dunes Lodge is a veritable oasis with a view of the waterhole that draws in wildlife day and night.

Mkulumadzi Lodge, Majete Wildlife Reserve, Malawi: This pool, perched above the confluence of the Shire and Mkulumadzi Rivers, is perfect for cooling off after a day out in Malawi’s Majete Wildlife Reserve. Surrounded by a riverine forest of marula, leadwood and star chestnut trees in a private concession, visitors will find true tranquillity in this piece of heaven.

Best for sundowners after a long day

Nothing can beat the magic of a sundowner on safari. But some spots offer just a little more magic than others – especially when you can float about, cocktail in hand.

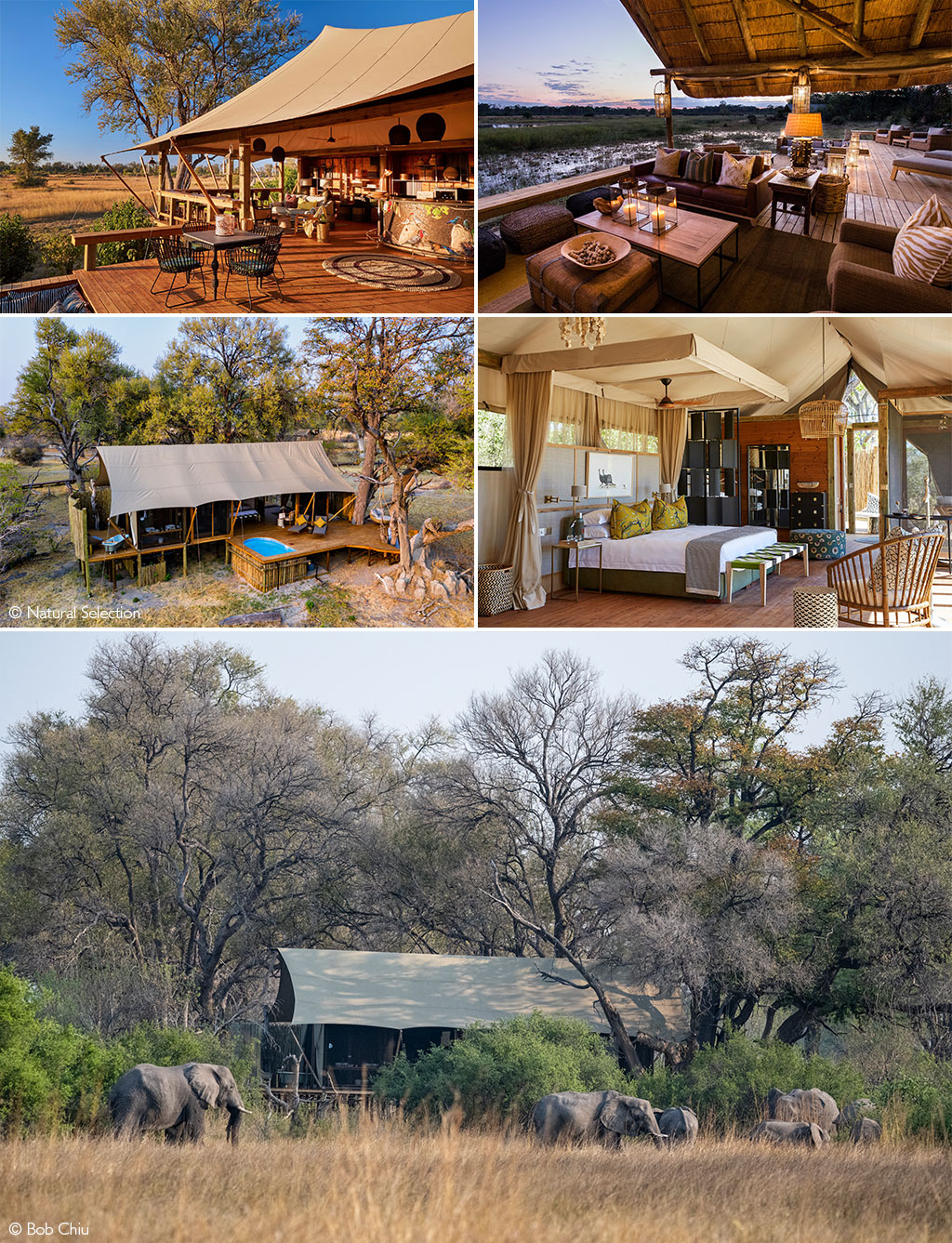

Duba Plains Camp, Okavango Delta, Botswana: Raised above the marshy Delta on decking made of recycled railway sleepers, each suite at Duba Plains features a private plunge pool – the perfect private spot to watch the sun go down and reflect on a day packed full of Okavango action.

Bakuba Lodge, Ankilibe, Madagascar: After a day exploring the nearby mangrove beach in the fishing village of Ankilibe, situated in magnificent southern Madagascar, this picturesque pool at Bakuba Lodge will offer welcome relief. Or choose to spend the day out taking a trip on the Onilahy River, and head back to the lodge to settle down for a local-rum cocktail.

Makanyi Private Game Lodge, Timbavati Private Nature Reserve, South Africa: The graceful curves of the Makanyi Lodge swimming pool are perfectly in keeping with the rest of the lodge aesthetic – graceful, yet unobtrusive in its bushveld setting.

Nile Safari Lodge, Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda: World-famous Murchison Falls National Park was one of the premier safari destinations in Africa and is once again a park on the rise. Nile Safari Lodge and its glorious swimming pool look out over a tranquil section of the Nile River from a raised riverbank.

Pumulani Lodge, Lake Malawi, Malawi: Gaze over the sunset flickering over the waters of Lake Malawi in this stunning infinity pool. Set on top of a hill in this fascinating part of the world, one could be forgiven for thinking they’ve found paradise. When you’re not treading water in the pool, head down to the lake-shore bar for cocktails on the beach.

Best for immersing yourself in your surroundings

Just when you thought your experience of these destinations could not get better… These pools will make you feel like you can reach out and touch the forest, ocean, mountains or river nearby.

Lemala Wildwaters Lodge, Kalagala Island, Nile River, Uganda: Watch the fierce rapids of the mighty Nile River come tumbling right past from the cool, calm comfort of the Lemala Wildwaters swimming pool. A visit to this remote and wild section of the Nile is like stepping back in time.

Denis Private Island, Seychelles: Does the idea of an infinity pool on a private tropical island seem like overkill? It isn’t, trust us. Rinse off the sea salt and float about in the shade, cocktail in hand.

Sundy Praia, Príncipe Island, São Tomé and Príncipe: Hidden in the veritable jungle, Sundy Praia is one of several historical plantations now overtaken by the wild forests of Príncipe. The crystal waters of the infinity pool merge perfectly with those of the Atlantic Ocean just beyond.

Track and Trail River Camp, bordering South Luangwa National Park, Zambia: Spend whole afternoons in this pool with views across the Luangwa river, surrounded by the sounds of the bush. Track and Trail River Camp is located on a breath-taking spot overlooking the South Luangwa National Park.

Jua Retreat, Zanzibar, Tanzania: Situated in the southeast of Zanzibar on the tip of the Michamvi peninsula, Jua Retreat’s beaches and immersion into nature promise an extraordinary experience. This pool, mere metres from the beach, offers the chance to soak up the sea air in the cool respite of one of Africa’s most beautiful pools.

Best for true luxury

As if the food, service, surroundings and safari are not enough: these pools epitomise the luxury offered by their respective establishments – and are perfectly selfie-worthy to boot!

Jack’s Camp, Makgadikgadi Salt Pans, Botswana: Jack’s Camp is resplendent in draped muslin and canvas – as is its pool. Shelter from the oppressive midday heat beneath the folds of the tent – a homage to a forgotten era of safari.

Chikunto Safari Lodge, South Luangwa National Park, Zambia: Boutique luxury ecolodge Chikunto is located on the iconic ‘Big Bend’ site overlooking the Luangwa River in South Luangwa National Park in Luangwa Valley. The saltwater counter-current swimming pool overlooks a waterhole, providing an inviting space to cool off and relax, or even get some exercise – in between adventuring in the bush.

The Motse, Tswalu Kalahari Reserve, Kalahari, South Africa: From the landmark Korannaberg mountains to the grassy, red dunes rippling away to the horizon, this vast tract of Kalahari wilderness is one of the most atmospheric destinations on our list.

The Oyster Box, Umhlanga Beachfront, South Africa: The Oyster Box does nothing in half measures – unapologetic grandeur and lavish interiors adorn every corner of this exclusive luxury hotel. Naturally, the swimming pool would have to live up to the standard throughout the rest of the hotel, which it does in absolute style.

The roads alternate between thick sand and clay that turns into sludge during the short rainy season. Phone signal is non-existent, and visitor density is extremely low, so it is not uncommon to spend the day exploring without seeing another soul. The northern section of the park tends to be slightly busier and offers greater concentrations of wildlife. This may all sound somewhat intimidating, but the result is more than worth the effort. This is, without doubt, one of the wildest parts of Southern Africa. The immersion in nature is absolute, and it is pretty easy to imagine one has this wilderness entirely to oneself.

The roads alternate between thick sand and clay that turns into sludge during the short rainy season. Phone signal is non-existent, and visitor density is extremely low, so it is not uncommon to spend the day exploring without seeing another soul. The northern section of the park tends to be slightly busier and offers greater concentrations of wildlife. This may all sound somewhat intimidating, but the result is more than worth the effort. This is, without doubt, one of the wildest parts of Southern Africa. The immersion in nature is absolute, and it is pretty easy to imagine one has this wilderness entirely to oneself.