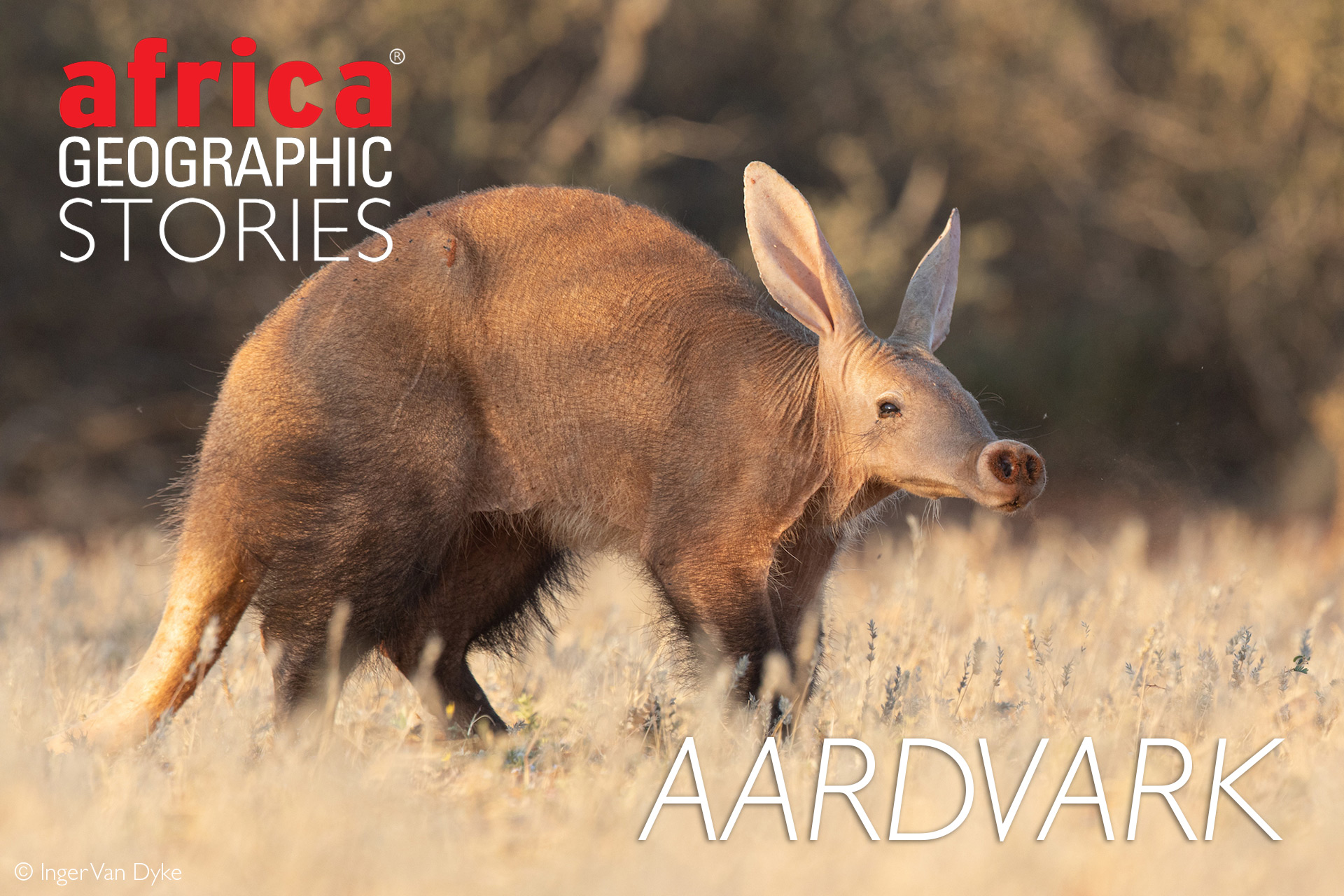

The “earth pig” of Africa

There are signs if you know what to look for… Some are obvious, like a pile of dark, freshly excavated soil or a massive entrance hole. Others are more subtle: adjacent patches of bare ground or a place where a shadow doesn’t fall quite right.

These signs hint at the existence of a network of secret tunnels, a daytime lair where one of Africa’s most fantastical animals slumbers beneath the ground: the aardvark.

The “earth pig”

The aardvark (Orycteropus afer) is one of a kind, devoid of close living relatives and the only surviving member of an entire order of animals, the Tubulidentata. Their otherworldly forms look as though they sprang straight out of the crazed imagination of an overly caffeinated fantasy writer. Giant, rabbit-like ears perch atop a bizarrely elongated head ending in a pig snout, and massive talons extend from each foot. Their stout, hunched bodies range from a dirty grey-pink to brown and thick skin is covered in a light smattering of hair. Finally, the “aardvark look” is completed by what could only be described as a giant, stumpy rat’s tail. Such an eclectic collection of features might, on paper at least, sound positively monstrous, but on the aardvark, the overall effect is somehow oddly winsome.

Of course, as is usually the case in nature, form follows function, and the aardvark’s unusual attributes are all perfectly suited to nights spent terrorising ants and termites before sleeping off a full belly in the safety of a comfortable underground den. Even the name “aardvark” is inspired by their excavation skills and subterranean habits, coming from an old Afrikaans word meaning “earth/ground pig”. The genus name “Orycteropus” translates as the “burrowing foot”.

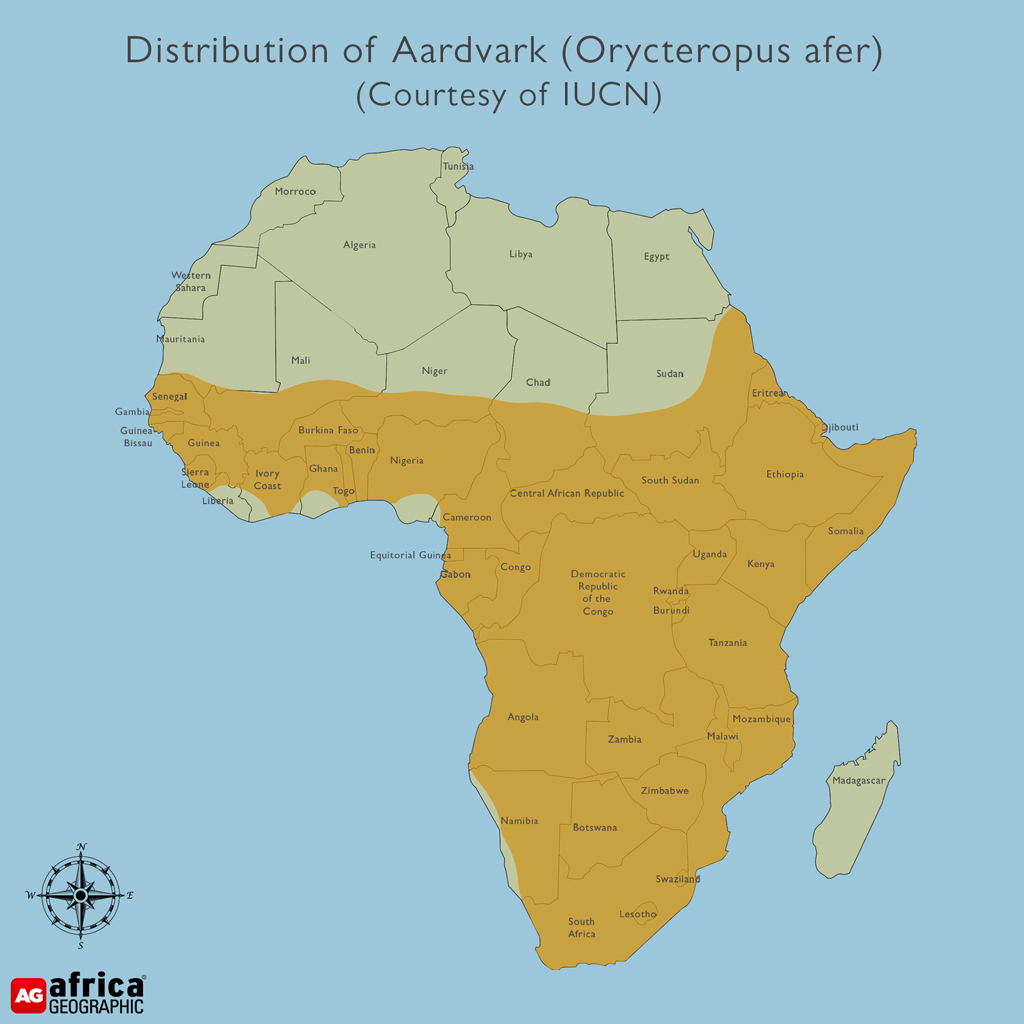

Although they have a widespread distribution throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa, few people are afforded more than a brief glimpse of the elusive and primarily nocturnal aardvark. Their secretive natures mean that information surrounding their behaviour, particularly social dynamics, is still somewhat scant. Consequently, the aardvark has more global renown as the first word in the dictionary than a fascinating and complex mammal.

Quick facts

| Length: | 1–2m |

| Mass: | 60–80kg |

| Social Structure: | Solitary |

| Gestation: | Seven months |

| Conservation status: | Least concern |

The nosey ones

Aardvarks subsist almost entirely on a diet of termites and ants (they are myrmecophagous), occasionally supplementing their water intake by snacking on the fruit of an aardvark cucumber. They emerge from their burrows as darkness descends (or slightly earlier during the colder, drier months) and set off searching for a meal, covering an average of around 2–5km every night. They move slowly, using their large ears and prodigious sense of smell to seek out termite and ant nests. Once located, aardvarks use their powerful claws to crack open termite mounds or dig beneath the soil, using a 30cm long tongue coated in sticky saliva to lap up the swarming insects. They will also make short work of a line of termites on the move.

Their characteristic noses are well suited to their gastronomic preferences. The tip of the snout is extremely sensitive and controlled by specialised muscles that allow it a high degree of mobility. Aardvarks, with their humongous ears and piggy snouts, also have more turbinate bones inside the nasal cavity than any other mammal, which is thought to increase the surface area for olfactory epithelium and improve their capacity to analyse scent molecules. When digging and feeding, these vulnerable nasal structures must be protected from both dirt and biting insects, and this is accomplished by a dense filter of thick nose hair and the ability to seal both nostrils tightly.

Despite some morphological and dietary similarities with New World anteaters, aardvarks and anteaters are not related, and any superficial resemblance can be attributed to convergent evolution. What sets aardvarks truly apart from any other mammal is their dental structure. The molar teeth do not have a pulp cavity or any enamel coating and instead consist of parallel tubes (hence Tubulidentata) of modified dentine held together by cementum. The sticky tongue approach to feeding means that copious amounts of sand accompany an aardvark’s meals, so the teeth wear down and are replaced continuously. However, the aardvark chews little while scoffing down tens of thousands of ants, so the muscular stomach takes over as a gizzard to further grind their food.

Dig it

Though aardvarks may have some of the keenest senses of hearing and smell on the continent, their eyesight is particularly poor. While foraging, they keep their ears pricked for approaching predators. Still, they become highly focussed when feeding, and it is surprisingly easy to creep close to a hunting aardvark unnoticed, provided one stays silent. As a result (and perhaps somewhat sensibly), they seldom stray far from a known bolt hole while feeding. When faced with a predator, their first defence is always to flee below ground. If necessary, they can dig out a tunnel up to a metre in length in less than five minutes.

However, this is not always possible, and, despite its rather bulky and cumbersome appearance, an aardvark is astonishingly fleet of foot and agile. Their long claws on shovel-like feet are formidable weapons if all else fails, and they will roll onto their backs to face a would-be attacker pointy side up.

Aardvarks dig different types of burrows: short tunnels for brief, overnight stays (“camping holes”), and dens with a straight tunnel ending in a round room and an extensive branching network with multiple entrances. Research shows that the temperatures in these tunnels fluctuate very little, acting as a warm refuge on cold days and sheltering their residents from the worst of the midsummer heat. Aardvarks move frequently, digging new dens every few days or weeks, and abandoned networks are often commandeered by warthogs, porcupines, hyenas, bats, mongooses, and even denning wild dogs (painted wolves).

The secret lives of aardvarks

The nocturnal activities of aardvarks leave behind very distinctive tracks to be discovered the following morning. Many a guide on a quiet drive or walk has pointed out a spot where an aardvark has stopped to feed, complete with claw marks and an indentation left by the tail. The guide will then invariably describe how one can tell it was a male aardvark due to two round indentations made by the scrotum. But alas! Contrary to prevalent belief, aardvarks have internal testes, and those impressions were likely left by the sizable scent glands found on both males and females.

The secretions produced by these scent glands have a profoundly pungent odour and are deliberately deposited when defecating and feeding. However, their exact function is still not fully understood. Given aardvarks’ low densities and extraordinary sense of smell, it is highly likely that these deposits offer a suitable means of indirect and long-lasting communication. Aardvarks are almost entirely solitary, but their territorial habits remain unclear. Home ranges often overlap, especially when food is plentiful, but whether or not they mark or defend territorial boundaries is unknown.

Aardvarks also likely use these scent marks as a coquettish communiqué between the sexes. Little is known about romances of aardvarks, though the male generally stays with his companion for the duration of her oestrus. Seven months later, the female gives birth to one baby belowground. Adult aardvarks may be fantastical and appealing, but it is somewhat challenging to extend such a description to their newborns. Without mincing words, newborn aardvarks are adorably ugly – pink, bald and wrinkly, with absurdly oversized feet. They are (unimaginatively) called cubs or calves. (If you have a better suggestion, they are all ears.)

After two weeks spent in the burrow’s safety, the baby begins to accompany its mother on foraging trips and will start feeding on solids some seven weeks later. By this time, it has acquired a hair covering and can now officially be described as cute. The youngster is fully weaned between three and four months old but will stay with its mother for at least a year. Occasionally, female offspring will remain with their mothers for an additional year, so it is not impossible to encounter a female with two different-aged youngsters.

Earth shapers

As far as we know, aardvark populations are still considered stable across much of the continent, and the IUCN currently classifies them as “Least Concern”. However, there are no definitive population estimates as aardvarks are somewhat challenging to count. Due to their low densities and cryptic natures, they may be declining in some areas due to habitat loss. Like all specialist feeders, aardvarks are also particularly vulnerable to sudden population declines.

While termites and ants may seem ubiquitous, survival in extreme environments can be tremendously challenging. In the desert, for example, aardvarks undergo dramatic internal temperature changes. They have to compensate for the bitingly cold winter nights by emerging earlier in the afternoon, limiting their available feeding windows and struggling to meet metabolic requirements. During these dry months, food is scarce. After a severe drought, the authors of one particular study recorded the deaths of five of their initial six aardvark subjects. Droughts are part of typical climate patterns, but weather extremes are becoming more common, and animals like aardvarks are likely to be severely affected by climate change.

These curious creatures are a keystone species. As biological engineers, they shape the landscape around them, and their tunnels are a vital resource to a multitude of mammal, reptile, and bird species.

Find one in the wild

Aardvarks may be challenging to find in the wild, but there are ways to improve one’s chances of spotting one. The best way to start is on a winter’s afternoon in some of the semi-arid areas of Southern Africa, like the Karoo or Green Kalahari in South Africa, Botswana’s Kgalagadi and Central Kalahari deserts and Namibia’s Damaraland.

Everyone should see an aardvark at least once in their lifetime – if only to marvel at the wonder of Africa’s many unique creations.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()