The horse-goats of the ungulate world

Taxonomists have prodigious power – their choice of the scientific name for everything from viruses to large mammals leaves behind an enduring historical footprint of our understanding of evolutionary relationships. In recent years, newly discovered species are given names based on everything from bad puns to popular culture (Agra vation – a type of canopy beetle, Polemistus chewbacca – a wasp). Taxonomists of old went in for a more descriptive approach, and while it is impossible to know whether or not it was ever tongue in cheek, the outcome is sometimes equally entertaining. Enter the Hippotragus (sable and roan antelope) – the two magnificent “horse-goats” of the ungulate world.

Hippotragus

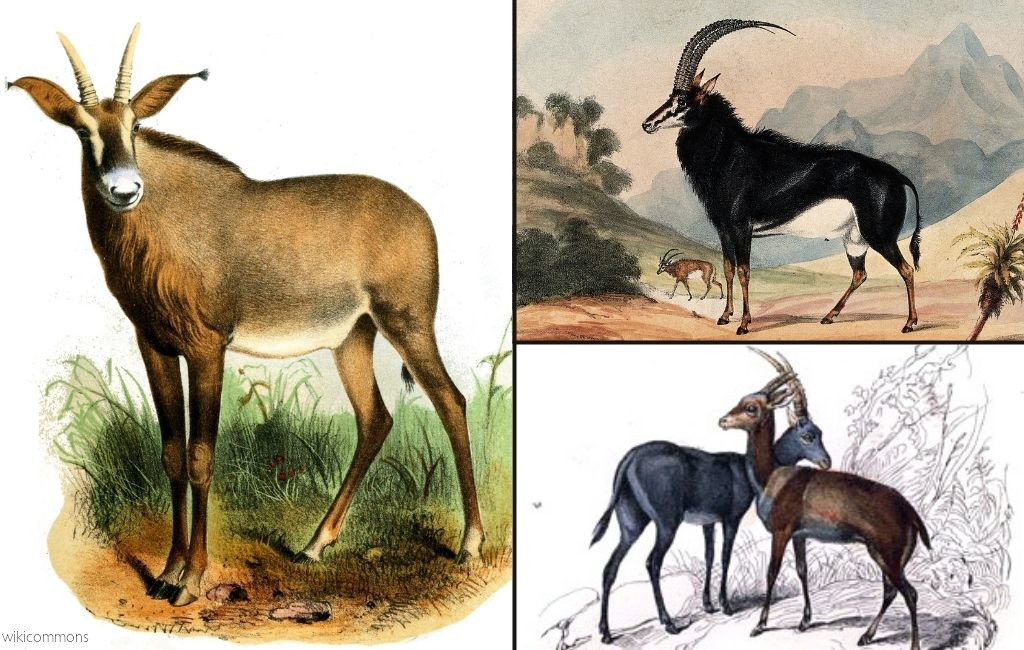

With long faces, caprine ears, and brawny, equine musculature, there is something “horse-goaty” about the only two surviving members of the Hippotragus genus. Both the roan and sable are among the most attractive antelope in Africa. Characterised by striking markings, robust bodies, and backward curving horns, the family resemblance between the two is evident in shape if not in coat colour (both species take their English names from the predominant colour of their fur).

One glance at their morphology should be sufficient to see an unmistakable resemblance to the oryx family, albeit with a different approach to weaponry. Thus, the roan and sable are grouped into the subfamily Hippotraginae (the “grazing antelopes”) along with the four oryx species and the addax – a collection of seven extant species belonging to three genera. These likely evolved from a common ancestor, with the Oryx and Addax settling in northern Africa initially and the Hippotragus adapted to the savanna habitats of the south. Ruminant classification, particularly antelope, remains a work-in-progress, but great strides have been made with recent genetic analysis.

Though the roan and sable diverged some five or more million years ago, they still show considerable similarities in behaviour, features and adaptations. Fascinatingly, even though they have spent millions of years evolving sympatrically (within overlapping ranges), recent evidence indicates that they can and do hybridise. Hybridisation is most frequently observed in Angola, where declining giant sable numbers (more below) have seen sable and roan interbreeding. This is sometimes referred to as Hubb’s principle or ‘desperation’ hypothesis and creates a vicious cycle where a rare species is more likely to mate with a similar species. (Disappointingly, there is no record that these hybrids are ever referred to as either “soans” or “rables”.)

Quick facts

| Roan | Sable | |

| Mass | 223-300kg | 220-235kg |

| Shoulder height | 135-160cm | 117-140cm |

| Gestation period | 278 days | 273 days |

| Number of young | One calf (twins occasionally recorded) | One calf (twins occasionally recorded) |

| Average life expectancy | Up to 25 years in captivity (around 17 years in the wild) | 15-20 years in captivity (less in the wild) |

Even without hybridisation, the tiny calves of sable and roan antelope are almost indistinguishable during their early months. However, by six months, the youngsters begin to take on the distinctive colouration of the adults. The two species stand almost the same height at the shoulder, but the roan is slightly taller and significantly heavier. Roan and sable are both specialist grazers and, as a general rule of thumb, both flourish in regions where competition with other grazers is reduced.

Sable and roan share a virtually identical social structure, with territorial bulls, a breeding herd of females and their youngsters and bachelor groups of immature or displaced males. The only significant difference is that roan breeding herds tend to be slightly smaller on average (5-15 as opposed to 15-22) but show more variation. Like many other antelope species, the bulls defend suitable territories (ideally with plentiful resources) and the females come and go, despite the male’s best efforts to detain them. The females have a strict hierarchy that is usually age-related and maintained by regular displays of low-intensity aggression.

The females hide their calves after birth and will only introduce them to the rest of the herd after a few weeks. The calves then spend most of their time with others of a similar age, and research indicates that sable calves, at least, have preferred playmates whose company they choose over others.

The IUCN Red List lists both species as ‘least concern’, but it must be remembered that these classifications are based on an overall view of the species and are not always applicable to specific regions.

Sable (Hippotragus niger – the “black horse-goat”)

The remarkable sable cannot be mistaken for any other antelope. The coat of the males is jet-black (hence the name), the inky hide broken only by vivid splashes of white on the belly and face. Adult males are equipped with sharp-tipped crescent horns that extend back over their arched necks. Males usually carry their heads high in a show of dominance except for threat displays when they drop their heads and scythe their horns from side to side. The females are furnished with arched horns, and while these are shorter and thinner than those of the bulls, they are still potentially deadly weapons. The cows lack the ebony sheen of the males, and their coats are more subtly chestnut coloured.

Sable can be exceptionally defensive when provoked, attacked, or injured, and, as adults, their only natural predators are lions and crocodiles (and very occasionally, Africa painted wolves and spotted hyenas). Like most antelope, sable are generally shy around people, but captive individuals are less nervous. A warning charge from a sable bull can be singularly terrifying. (Watch here for an entertaining insight into how quick wildlife vets need to be on their feet.)

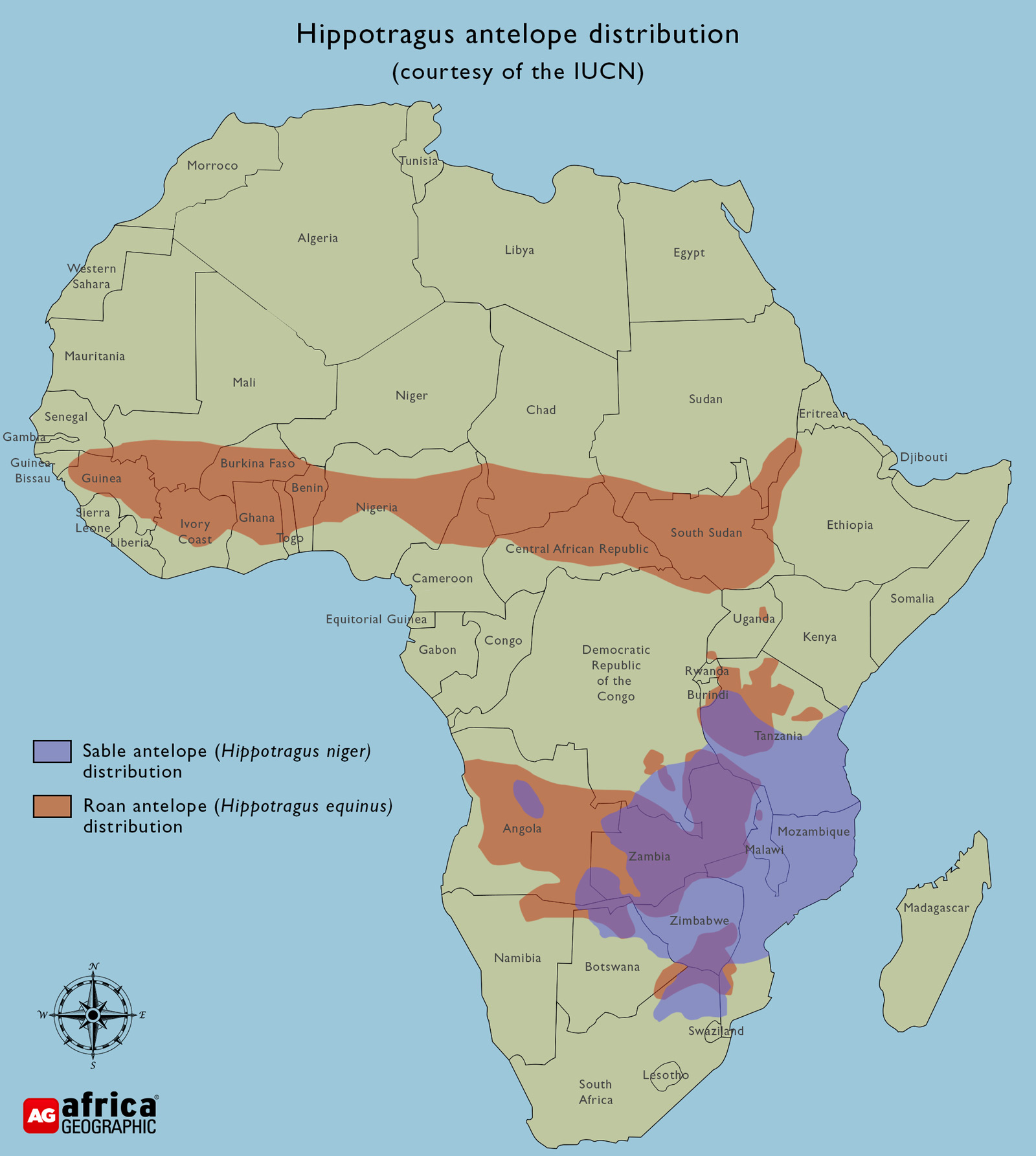

Sable have a preference for miombo woodland and are found in savanna and grassland habitats across south-east and south-central Africa, with a small isolated population found in Angola. While classified as specialist grazers, they readily browse during the dry season when they compensate for poor grazing with leaves and forbs. There are four recognised subspecies of sable (though the validity of these divisions remains in question and most are not yet recognised by the IUCN): the southern sable (H. n. niger), Zambian sable (H. n. kirkii), eastern sable (H. n. roosevelti) and the giant sable (H. n. variani).

Though the first three subspecies occur in relatively stable numbers, the resplendent giant sable of the Angolan savanna is critically endangered. Despite being a national symbol of Angola, the latest assessment of their numbers by the IUCN suggests that fewer than 250 mature individuals remain. As the descriptor “giant” indicates, they are the largest of the four sable subspecies, and their horns can reach over 1.5m in length.

Roan (Hippotragus equinus – the “horsey horse-goat”)

As their vernacular name suggests, roan range in colour from a pale grey to reddish-brown, with their faces marked by bold black and white patterns. They are the second tallest and third heaviest antelope in Africa. Their horns are proportionately shorter than those of the sable (the record is just over 90cm) and are slightly less curved. The sexual dimorphism is considerably less marked in roan, and adult females are only fractionally smaller than the males. The most beguiling feature of roan antelope is their elongated and angled ears, which add a somewhat absurd edge to an otherwise handsome animal. Like sable, roan are placid until provoked, at which point they fight viciously and have been known to kill lions in self-defence.

Roan antelope inhabit woodland and grassland savanna habitats, and their range overlaps with that of the sable in several areas. However, roan are the only Hippotragus antelope found north of the Equator and across into West Africa. Six subspecies are currently recognised, which has made fragmented populations challenging to manage and added to conservation challenges. There are parts of Africa where the roan numbers have plummeted, particularly in South Africa’s Kruger National Park and the Ruma National Park in Kenya.

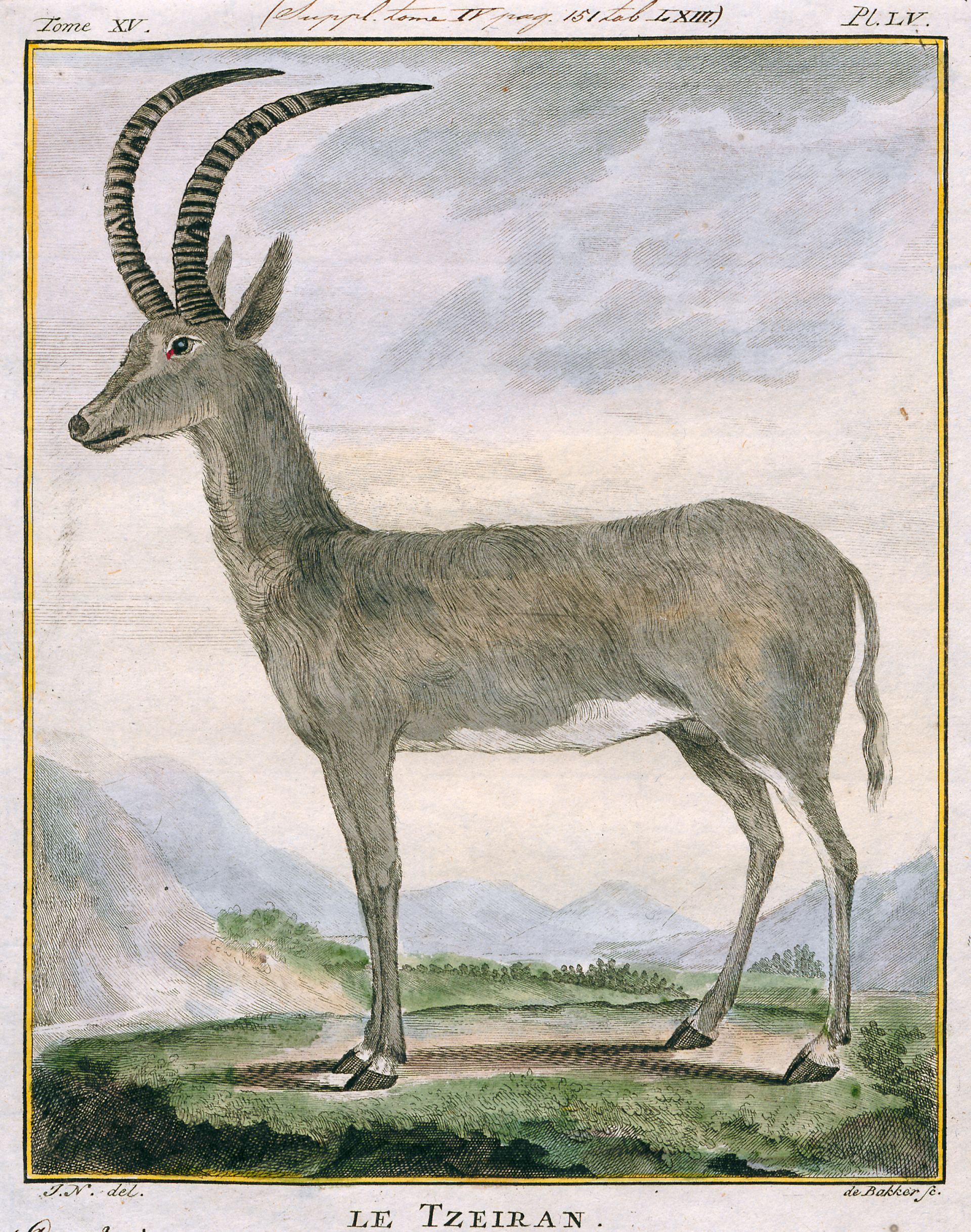

Bluebuck (Hippotragus leucophaeus– the lost “horse-goat”)

Until the late 1700s, a third Hippotragus antelope roamed the southern tip of Africa. The bluebuck was the first large mammal to become extinct in historical times, hunted to extinction around 1800 and followed shortly by the quagga a few years later. The unfortunate bluebuck was likely restricted to a small range within the Cape area of South Africa. And genetic studies indicate that bluebuck numbers were low even before European settlers arrived in South Africa. Though hunting finished them off, there were likely several other contributory factors, including disruption of ancient migratory pathways due to natural climate shifts, loss of habitat and competition with roan and then livestock.

While the blue buck was once considered a subspecies of the roan, genetic studies confirm that it was a distinct species. However, experts have had to work extremely hard to clarify its exact history because many of the collected specimens were either roan or sable. The bluebuck was probably more closely related to the sable, with a small population becoming geographically isolated and eventually evolving into a separate species.

Slightly smaller than both sable and roan, the bluebuck was likely equally attractive and charismatic.

Where to find them in the wild?

Though both sable and roan have a relatively widespread distribution throughout Africa, there is nowhere that they could be considered to be particularly common. Moremi Game Reserve and Chobe National Park in Botswana, as well as Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe are good places to spot both. Malawi’s Nyika Plateau is an excellent location to view roan antelope, as are the Busanga Plains of Kafue in Zambia. The miombo woodlands of southern Tanzania and western Zambia both support large populations of sable.

For camps & lodges at the best prices and our famous ready-made safari packages, log into our app. If you do not yet have our app see the instructions below this story.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()