Kenya's iconic predators find some unlikely allies

Story first published on bioGraphic

Dawn is just breaking when Kamunu Saitoti sets out across the Amboseli bush in search of lions. At first glance, he appears much like any other Maasai warrior: Lean and tall, his dark red shuka is wrapped around his torso and waist concealing his only weapon, a long knife with a simple wooden handle. Brightly coloured beads adorn Saitoti’s neck, ears, forearms, and ankles, and his feet, far more weathered than the rest of his body, are only partially covered by dusty sandals fashioned from discarded car tyres.

“I killed my first lion when I was 21,” Saitoti says as he scans the horizon. In all, he has killed five lions. This, he says, was an integral part of his family history, part of being raised as a moran, a Maasai warrior. “My brother and father have also killed lions.”

The Maasai are traditionally a nomadic people subsisting almost exclusively on the milk, blood, and meat of cattle grazed on East Africa’s vast rangeland, amidst what once appeared to be endless numbers of wild animals. In the past, lion killing for the Maasai was as much about tradition as it was about protecting livestock from predators. To hunt and kill a lion was a critical right of passage known as olamayio – how young Maasai males became men. The tradition has also created a powerful connection between warriors and lions, with each young moran receiving a lion name after his first successful hunt. Saitoti’s lion name, Meiterienanka, means “one who is faster than all the others.”

But traditions are beginning to change.

On this day, in place of a spear, Saitoti carries a radio telemetry kit. He unfolds the antenna in a manner suggesting he has done this countless times before and looks around in search of a hill – not an easy task in a landscape as flat as this. He settles for the remnants of an abandoned termite mound and begins to scan for a signal. Once he has a sense of the direction the signal is coming from, he packs away the kit and starts walking, dust trailing his brisk march along the well-used track.

For the next three hours, Saitoti stops only to look for signs of lions, or to talk to herders. Most tracks he sees are too old to bother with, but as the sun nears its zenith, he finds a set that elicits visible excitement – a departure from his otherwise solemn demeanour. Lion cubs, young ones, and very fresh. Patience, however, will be required here. The narrow trail leads into a maze of dense shrubs, and that is no place to follow a lioness with cubs – even for someone as experienced as Saitoti.

At 36, Saitoti is a seven-year veteran, and one of Kenya’s three regional coordinators, of an organisation known as Lion Guardians. Established in 2007, the program is dedicated to finding ways for Maasai and lions to coexist. At its core is a shift in the relationship between the moran and the lion: Hunters have become protectors.

This profound change in perspective is a critical component of East Africa’s lion conservation efforts. But the Guardians have a lot of ground to cover – just 45 Maasai warriors patrol about a million acres of Kenyan rangelands – and human-wildlife conflict is a bigger problem than one organisation, or one approach, can solve.

Lion Guardians is just one of several small- and medium-sized efforts by government officials, NGOs, and locals to reduce human-wildlife conflicts in Kenya and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. As human populations in the region have exploded, consuming increasing amounts of wildlife habitat in the process, the numbers of some of the region’s most iconic and important species have been in steep decline.

Populations of many of Kenya’s large herbivores have fallen by 70 to 90% since the late 1970s. And as their prey has become more scarce, so too have lions. Scientists estimate that lion populations have fallen by more than 40% in the past 20 years, and the 20,000 or so wild lions that remain occupy just 8% of the species’ historical range.

In many ways, the need for such intervention has never been greater. Yet, in a region where droughts are frequent, and famine is never entirely out of sight, finding a path toward peaceful coexistence between herders and the predators that hunt their livestock will require a great deal of persistence, creativity, and a shift in how the region’s wildlife is valued.

Human-wildlife conflict

For most Maasai, the response to finding a leopard in your goat pen, surrounded by several slain goats, would be quick and straightforward: Kill the leopard. There would be no repercussions, as Kenya’s wildlife laws allow citizens to dispatch so-called problem animals. And this young male, like his mother before him, would certainly fit that description. He had been terrorising the village of Ngerende and several neighbouring communities for years, killing hundreds of goats – losses keenly felt in what is one of Kenya’s poorest regions, and a hotbed of human-wildlife conflict.

With the leopard’s paw now caught in the fencing of the pen, or boma, as livestock enclosures are called here, there seemed to be only one possible outcome. But the owner of this particular boma, Mark Ole Njapit, is no ordinary Maasai.

“I understand the value of wildlife for the future of our people,” says Njapit (48), a Ngerende community elder known by most as ‘Pilot’. “Everyone was agitated and wanted to spear it, but I calmed them down and called KWS (Kenya Wildlife Service).” Fortunately for the leopard, KWS officers were treating some elephants nearby and responded quickly. After tranquillising the cat, they were able to cut him free and move him to an area where he would be less likely to get into trouble.

That was six months ago. Today, Pilot is supervising as members of his village – in partnership with the Anne K. Taylor Fund (AKTF), an organisation working in its own way to reduce human-wildlife conflicts – construct his new boma.

The enclosure they’re building is formidable, with welded corner posts interspersed with termite-proof eucalyptus timber poles, all set in concrete. The chain-link fence is stretched tight, 7 feet above the ground and another foot buried in the soil; the fence is designed to be virtually impossible for a predator to push over, climb, or dig beneath. (While a leopard could easily scale a similar-sized fence constructed entirely of wood, they tend to avoid chain-link fencing.)

Today, after more than two years and nearly a hundred of the latest iteration of AKTF bomas constructed, the program’s record remains intact: Not a single livestock animal protected by one of these enclosures has been killed by a wild predator.

The effectiveness of the new bomas means they’re in high demand. And while AKTF doesn’t usually work in villages as far north as Ngerende, when Pilot reached out, the program’s construction director, Felix Masaku, made an exception.

“Here is a man whose small village loses maybe ten goats a week choosing not to kill the leopard that is doing much of that damage. That is very unusual, and it is important to support this man so others might follow his example,” says Masaku.

In general, AKTF priorities cases in which livestock losses have been most significant.

“This is about conservation and co-existence,” Masaku continues. “We want to minimise conflict and retaliatory killings. If someone is losing five goats and two cows every week, that person is more likely to try to kill predators than someone who loses maybe one goat a month.”

By reducing the vulnerability of livestock to predation, this program and others like it aim to reduce, if not eliminate, retaliatory killings, known as olkiyioi. This practice poses a grave threat to lions in particular, especially when angry cattle owners turn to poison rather than spears to wipe out entire prides of lions. In recent years, there have been several high-profile killings. For example, several members of the Marsh pride (of BBC Big Cat Diary fame) were deliberately poisoned in the Maasai Mara National Reserve (MMNR) in 2015, and six lions, including two cubs, were speared to death outside Nairobi National Park in early 2016.

One troubling detail about the slaughter of the Marsh pride members is that it was carried out by Maasai seeking revenge for cattle killed while being grazed illegally inside the reserve. This practice is not uncommon. In fact, a paper published in the Journal of Zoology in 2011 estimated that by the early 2000s, livestock made up 23% of the MMNR’s mammal biomass – up from a mere 2% a few decades earlier. Today, this figure dramatically exceeds that of any resident wildlife species in the protected area except for buffalo. This is as much a sign of declining wildlife populations as it is of human incursions into the reserve, and it underscores significant challenges both in terms of protecting livestock and preventing human-wildlife conflicts.

As Anne Taylor, the founder of AKTF, put it: “Inside the bomas is one thing, but keeping cattle safe if they are literally brought into the lions’ den is virtually impossible.”

Finding a solution

For many Maasai today, lions and other predators have become an expensive nuisance at best, and a source of deep-seated resentment at worst. In general, this resentment is not directed toward the predators themselves, but toward a government – and the world at large – which often appears to place more value on the big cats (and the tourism dollars they generate) than on Maasai lives and livelihoods.

National parks and reserves cover a mere 8% of Kenya’s land area and support only a third of its wildlife. The remaining two-thirds of the country’s wild animals inhabit private and communal rangelands. This is land they share with the Maasai, Samburu, and other pastoral people. Many think it is here, outside of the parks and reserves, that the future of Kenya’s wildlife will be decided.

According to a report co-authored by Panthera, WildAid, and the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, loss of habitat due to agricultural expansion, which invariably pushes wildlife into closer contact with farmers and pastoralists, is the underlying factor of all major threats that lions face.

To many, the conversion of unprotected rangelands to agriculture might seem inevitable as the region’s population grows. Still, Calvin Cottar, a fourth-generation Kenyan whose great-grandfather emigrated from Iowa in 1915, disagrees. According to Cottar, it all comes down to economic security.

“We are talking about some of the world’s poorest people,” Cottar says. “For them, it is about survival. Why should we expect them to care about lions or elephants when they are struggling to put food on the table – if they even have a table? Wildlife is costing them money, not earning them money, and that is what has to change.”

Toward this end, while working with the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), Cottar initiated several district wildlife associations in an attempt to help landowners acquire ownership rights to the wildlife residing on their lands. Because all wild animals in Kenya have historically been considered the property of the state, benefits to local communities having to co-exist with these creatures have generally been few and far between. Now in his 50s, Cottar says there’s much more to be done. He is more convinced than ever that the future of Kenya’s wildlife lies with the people sharing the land with them – and with a shift in government policy.

“It’s really quite simple,” he says. “We all have to pay for ecosystem services. Pay the Maasai landowners a monthly lease for their land in return for leaving it intact. The problem is that wildlife has no value to them, whereas cattle and commercial agriculture do.”

While removing snares, building livestock enclosures, and monitoring lion populations are all essential management practices, Cottar says, they don’t solve the root cause of human-wildlife conflict. Wild animals are basically a nuisance and a liability to the Maasai, he explains. “We have to make maintaining wildlife the most productive land use, and preferably in a way that respects the Maasai lifestyle and culture.”

That is why Cottar now finds himself sitting in a circle with perhaps 50 Maasai – young and old, men and women. The topic, just as it has been for the last three years, is the formation of the Olderkesi Conservancy, on the land where Cottar’s safari camp currently stands. In general, the conservancy model consists of land being leased directly from its owners for conservation purposes. Olderkesi is slightly different in that the 100,000-hectare ranch has yet to be subdivided, making it the last communally owned ranch left in Kenya. As a result, the land will be leased from a trust representing all 6,000 landowners, and because the agreement involves the Maasai, a complete consensus is required before anything can be signed. In Maasailand, patience is not so much a virtue as an absolute necessity.

One of the community’s most respected elders joining Cottar in the circle is Kelian Ole Mbirikani (58), a member of the Olderkesi Land Committee and Chairman of the Olentoroto landowners group, which owns the land immediately surrounding Cottar’s camp. He is also one of the driving forces behind the conservancy initiative.

“The Maasai depend almost completely on their cattle,” Mbirikani explains, “so convincing them that it is possible to have both wildlife and livestock at the same time has been our biggest challenge. In their experience, when land is set aside for wildlife, all of the cattle disappear. That’s what national parks do.”

Mbirikani is convinced the conservancy concept can work, though. He and a group of other Maasai travelled with Cottar recently to conservancies as far north as Samburu. There, they saw wildlife and met landowners who are still able to graze their cattle. “The people are really benefiting,” Mbirikani says. “Their children are being educated all through university level with the money from the conservancies. That is what we want for our people, too.”

There are nine other conservancies around the MMNR, and a handful more in other parts of the country, which all make regular, direct payments to local landowners. Similar approaches have been employed by Wilderness Safaris in Namibia and the Nature Conservancy in the United States, among others. While none of them can be said to offer financial benefits on the same scale as Olderkesi, Cottar is not alone in seeing this as a promising solution.

Indeed, two studies published last year demonstrate the effectiveness of Kenya’s conservancy approach. According to one of these assessments, despite lack-lustre political support conservancies managed to achieve “direct economic benefits to poor landowner households, poverty alleviation, rising land values, and increasing wildlife numbers”. The other study saw a direct positive effect on lion populations within Kenya’s conservancies, with a nearly three-fold increase in just ten years.

However, while these results seem promising, there will always be areas outside of conservancy boundaries – borderlands and buffer zones – where human-wildlife conflict are bound to continue. There’s not enough funding available to expand the conservancies enough to eliminate these conflict zones. The question, then, is whether people can learn to co-exist with lions and other wildlife even when there is no monthly payment to be collected.

The lions and their Guardians

As Kamunu Saitoti waits patiently, hoping to glimpse the new lion cubs when they finally appear from the thicket, he is joined by a younger Lion Guardian, Kikanai Ole Masarie. Not long after, a battered Land Cruiser arrives with one of the organisation’s founders, Director of Science Stephanie Dolrenry. The two warriors pile into the vehicle, and they all set off in search of the cubs.

“These lions are not like those in the parks,” Dolrenry explains. “There’s no tourism here, so they are not habituated to people or cars. We’ll be lucky if we find them at all. They can be extremely shy, especially with young cubs.”

But this is a lucky day, it seems. With thorny acacia bushes screeching against the glass and metal of the bouncing vehicle, the team suddenly finds itself in a veritable crowd of cats. Dolrenry, like the Guardians, can identify them all. Mere metres from the car, Meoshi, her three cubs, and her mother, Selenkay, lounge in the shade. A few dozen paces away, but on their way to join them, Meoshi’s sister Nenki with her own four cubs. Much smaller than Meoshi’s, these were the young lions whose tracks Saitoti was following. This is the first time anyone has laid eyes on this new generation.

“Selenkay is a bit of a celebrity around here,” Dolrenry says. “She causes problems like no other lion, but she’s a tough one, and it’s hard not to admire her.”

Saitoti nods. Selenkay is his favourite lion – her guile and tenacity are something to be respected. She and her family frequently target cattle and give the Guardians plenty of headaches. She has been hunted more times than anyone cares to remember. One of her sisters has fallen victim to poison, and so too has one of her mates, while another sister was killed by spear. She has endured three male takeovers and has even attacked a Maasai moran to protect her young cubs. Like the owners of the livestock she frequently kills, she is a true warrior.

But her legacy is far greater than her own reputation. Her longevity, itself the result of the unyielding commitment of Saitoti, Masarie, and the other Guardians and the growing tolerance of the Maasai inhabiting these rangelands, has helped to connect populations in vital conservation areas and has added much-needed genetic diversity to established prides. One of her sons has made it as far north as Nairobi National Park where he is now breeding successfully.

Saitoti did not become a Guardian because he loved lions. Instead, he was in trouble and needed a job. Arrested for being part of an illegal hunt, his father had to sell three cows to have him released on bail. That made him reconsider his path. Killing lions, despite bringing prestige and honour, also brought hardship.

“For the first two years my feelings about lions were the same,” Saitoti says. “This was just a job. But slowly, things began to change. They give food for my family, and they help educate my children. I even buy veterinary medicine for my cattle with my salary from the lions.”

“And we still get the girls!” Masarie chips in with a broad smile, referring to the social status that killing lions – and, more recently, protecting lions – can bring to a young Maasai man. At 24, he is part of a younger generation of Guardians, and his words are significant, as they hint at an ability for long-held Maasai beliefs and traditions to change.

“The other warriors mostly stay at home, but we are close to the lions every day, tracking them and finding lost cattle. The girls know we must be very brave!” Masarie adds.

Saitoti smiles and continues: “For me, now, I feel there is no difference between the lions and my cows at home. I care about them equally.”![]()

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Marcus Westberg

Marcus Westberg is an acclaimed photographer and writer, focusing primarily on conservation and development issues in Sub-Saharan Africa. A photojournalism finalist in the 2015 Wildlife Photographer of the Year, Marcus works closely with several non-profit organisations and projects across the continent. He is a conservation and community development advisor for Luambe Conservation in Zambia.

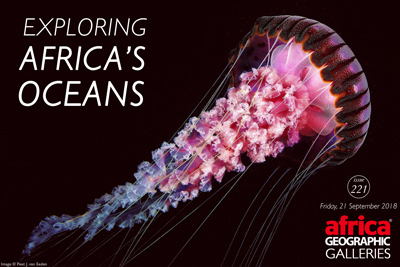

ALSO IN THIS WEEK’S ISSUE

Exploring Africa’s Oceans Gallery

Home to some of the most spectacular and treasured life, the oceans and seas surrounding Africa contain a multitude of creatures that thrive in the warm and cold currents that run along our continent. Various bodies of water surround Africa – the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Suez Canal and the Red Sea along the Sinai Peninsula to the northeast, the Indian Ocean to the east and southeast, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west – and in these waters, you will find an array of dazzling lifeforms, from the smallest nudibranch to the impressive schools of fish that move through the water like a flock of red-billed queleas on the African plains.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()