The Kruger - evolving conservation success story

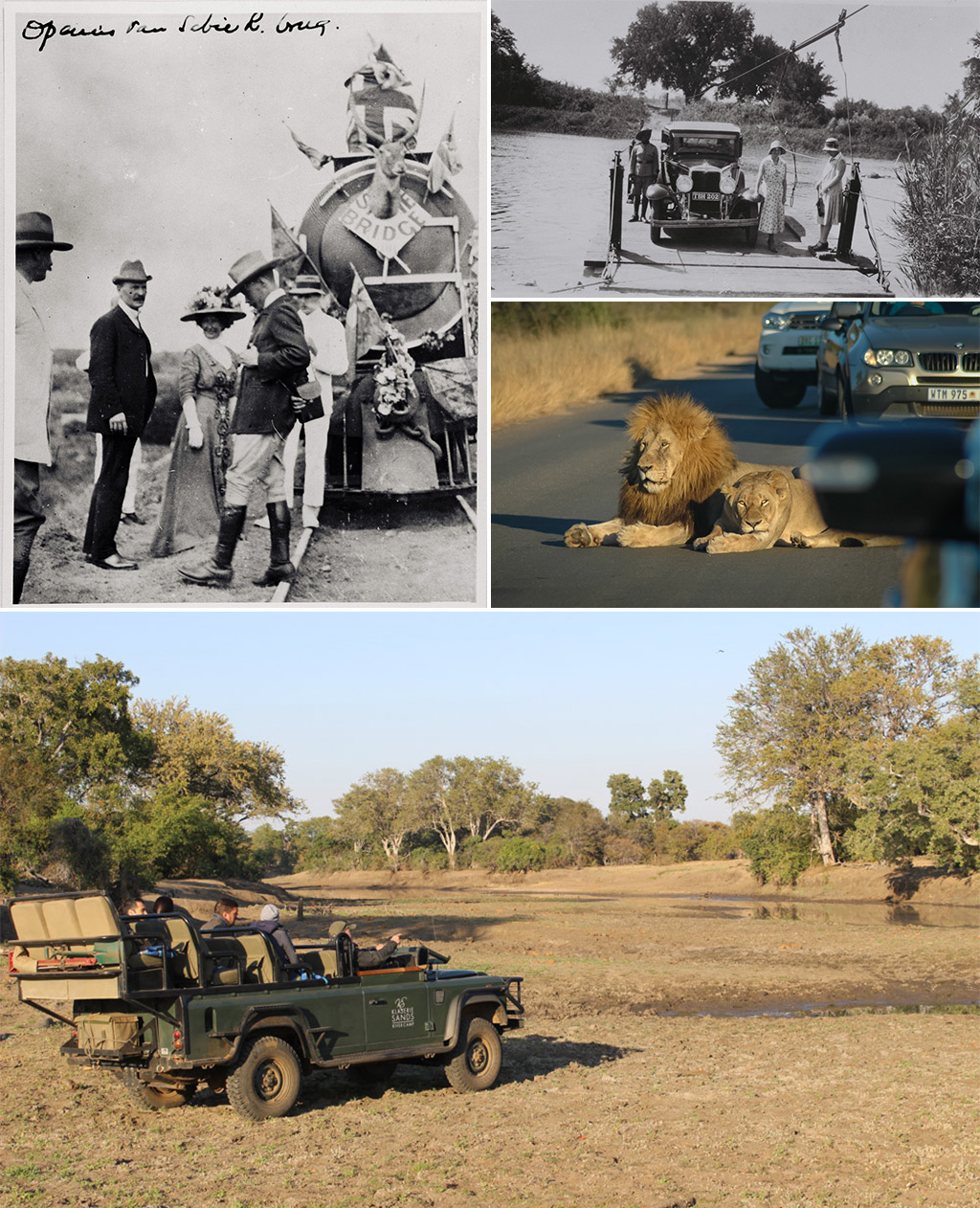

It was a few years before the South African (Boer) War, in the late 1800s when President Paul Kruger (in office 1883 – 1900) was alerted by James Stevenson-Hamilton to the fact that a rapid extinction of various species of flora and fauna was taking place in South Africa. Unregulated hunting meant that wild animals were disappearing fast, and President Kruger had his eye on a piece of land he wanted to turn into a reserve.

MAKING A PARK

In 1898, he managed to declare the area between the Sabie and Crocodile rivers a game sanctuary and restricted hunting zone – which he called the Government Game Reserve, subsequently renamed to the Sabi Game Reserve. This was a time of great upheaval, during which President Kruger declared war on the British Empire, a war that ended in 1902.

In 1903, the area between the Sabie and Olifants rivers was added to the reserve, and by the end of 1903, the Shingwedzi Game Reserve was proclaimed – covering the area between the Letaba and Levuvhu rivers. The subsequent addition of further farms added to this vast protected area.

Hunting was forbidden, but wildlife was still scattered and skittish. Staff were appointed, and James Stevenson-Hamilton became the first park warden. He became renowned for his dedication to conservation and famously disapproved of the tarring of the roads in the reserve, believing that people would then drive faster, resulting in the unnecessary deaths of wild animals. This man could see well into the future!

It soon became clear that the only way to secure the future of wildlife in the reserve was to establish it as a national park under the South African Union Government. Unfortunately, this idea was short-lived, as in 1914 World War I broke out, resulting in many of the staff leaving for active service. The poor state of the economy meant that most departing staff were not replaced.

With the lack of staff, the reserve suffered from rampant poaching. There was a single police sergeant at Komatipoort, to the south of the reserve, whose job it was to singlehandedly defend that section of the park. Also, soldiers returning home from the war hoped to be given the land for sheep farming.

At the time, it looked like the reserve would never recover, but by 1919 things started to improve. The staff numbers had increased again, and the discussion once again arose about the declaration of a national park.

Finally, on 31 May 1926, the National Parks Act was drawn up and passed by the Houses of Parliament, and the Kruger National Park was officially established.

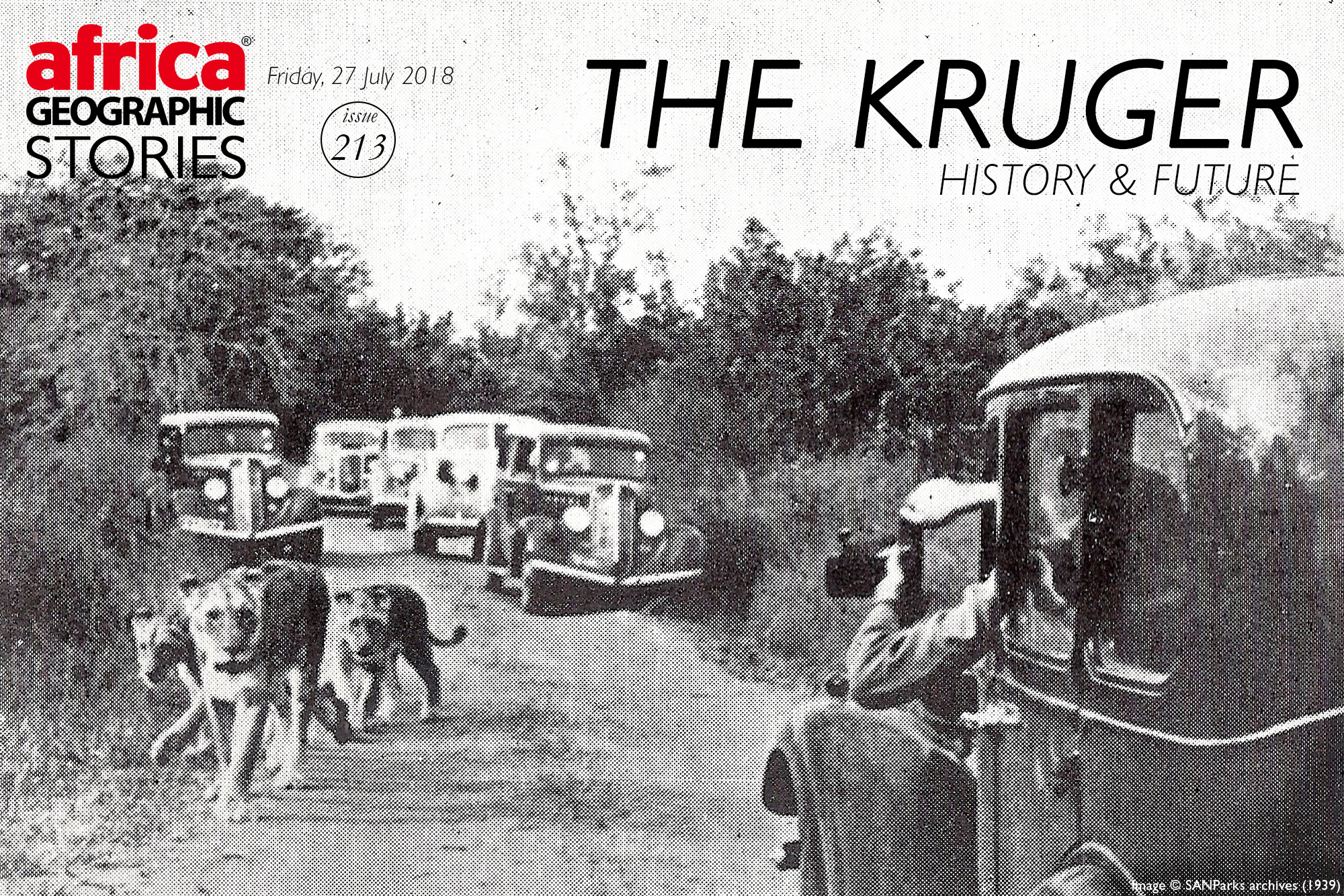

WELCOME TOURISTS

The first ‘real’ tourists were welcomed to the park in 1926. Before that, in 1922, there were railway tours that passed through the reserve – the trains would stop for one day in the park to allow passengers to view the wildlife.

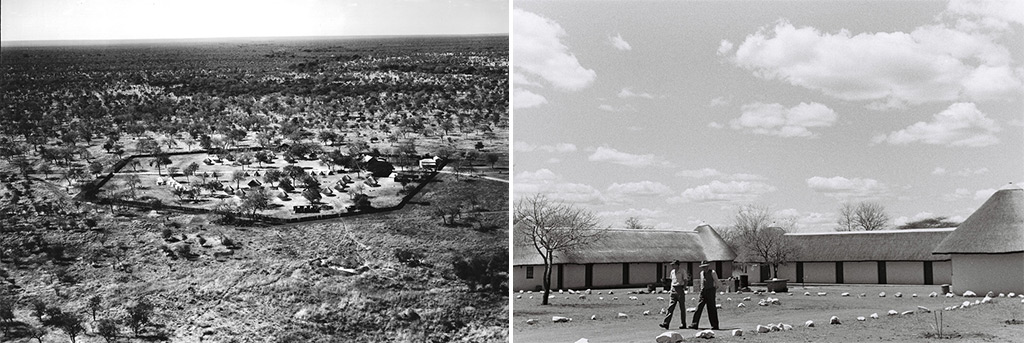

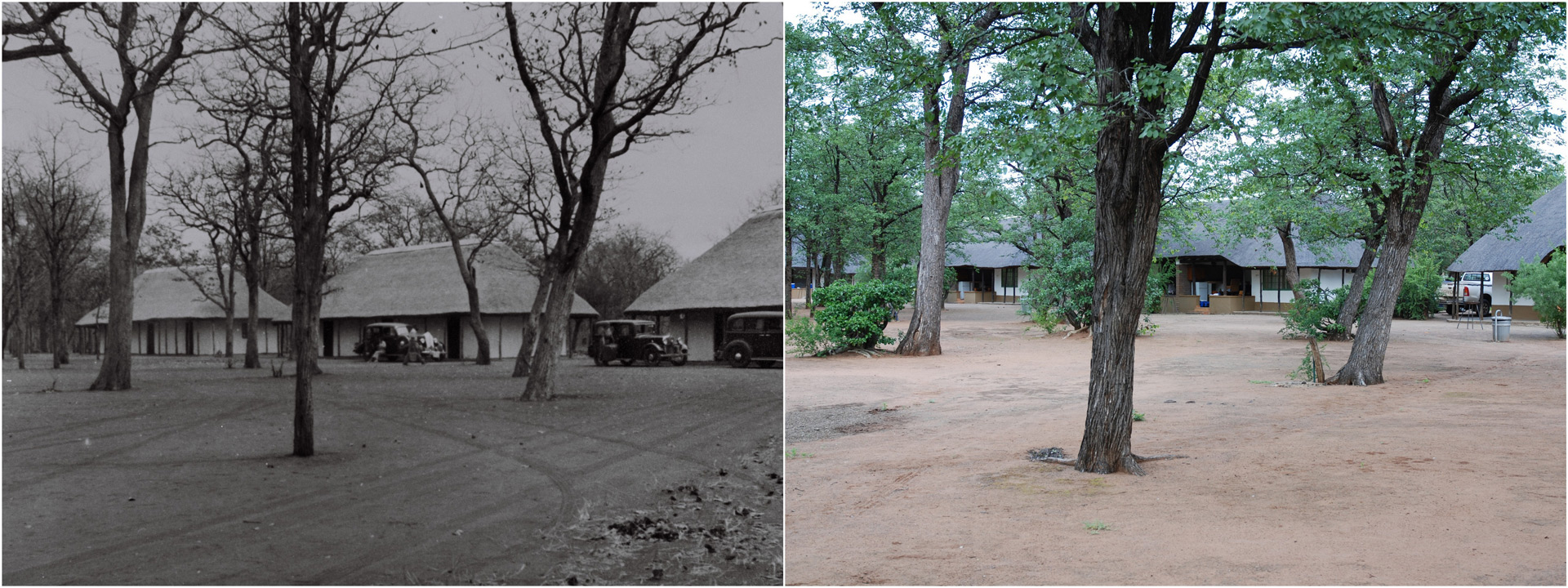

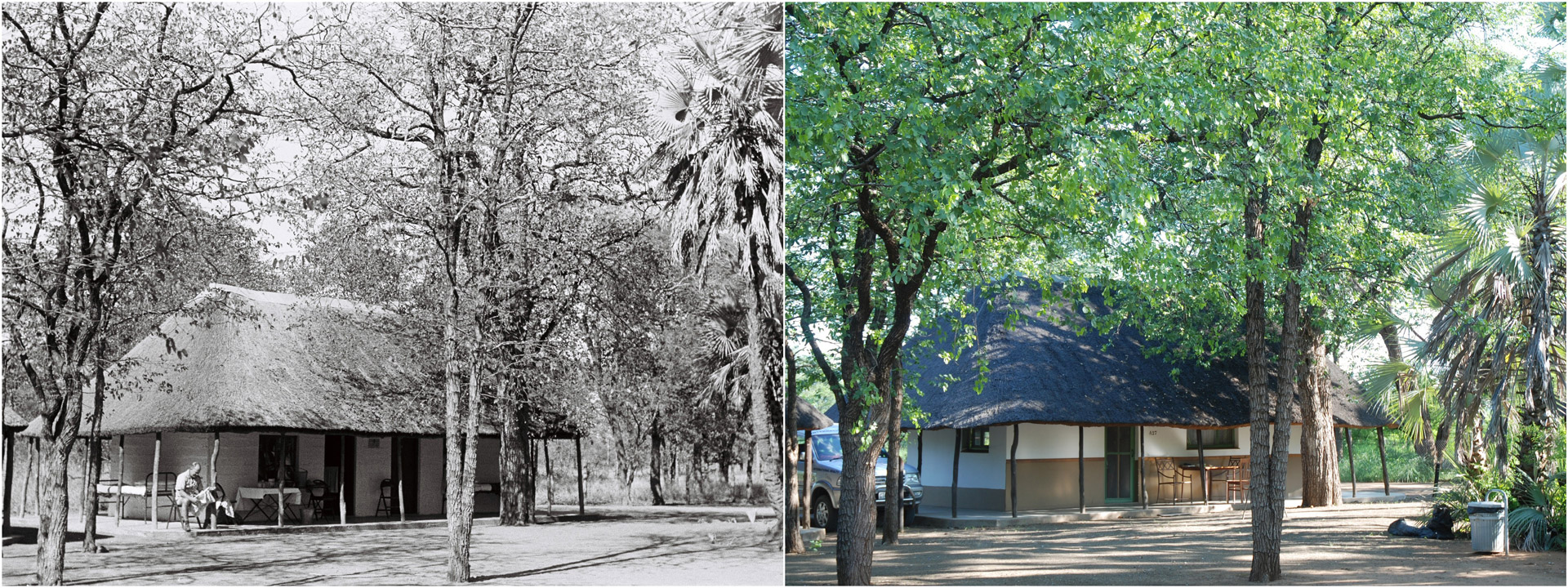

It was only in 1928 when the first tourist facilities were constructed in the park. Satara, Pretoriouskop and Skukuza (then known as Sabi Bridge) became the first locations for overnight huts. A tented camp was erected on the banks of the Luvhuvhu River in the far north of the park, but after being hit by floods, and swamped with mosquitos, it was concluded that it was, in fact, not the ideal location to bring tourists. Everyone involved was new to this, and through trial and error, the park began finding its feet.

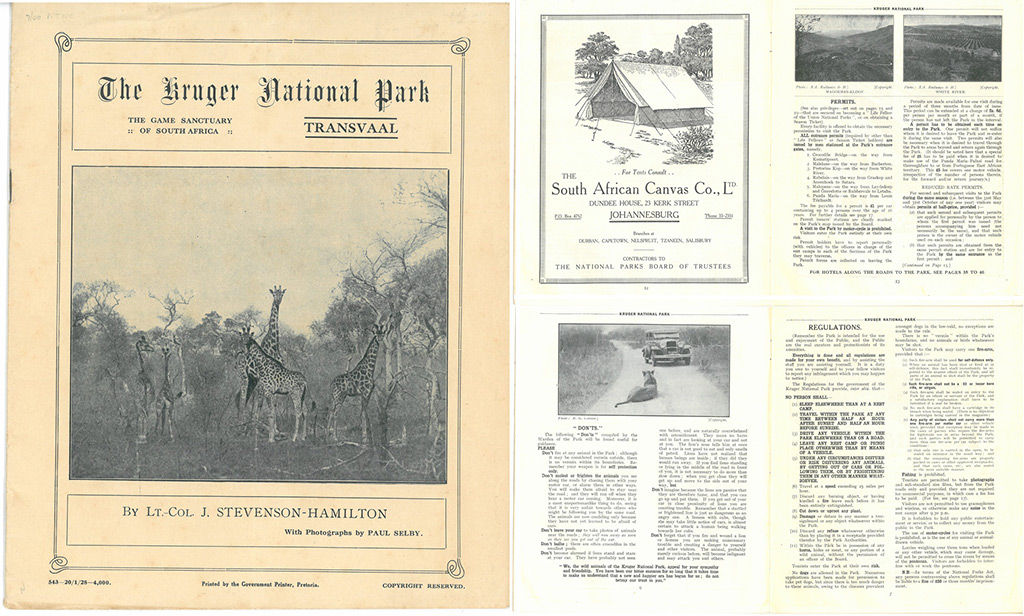

NO RULES

The late twenties seemed like a laid-back time in Kruger’s history. The only real rules that applied were to leave your firearms at home and pay your fee of one Pound at the gate. Other than that, you were a free agent. Guests weren’t even required to return to their cabins at night. Instead, they could camp out under the stars. Those early pioneering Kruger guests must have had a few adventures and stories to tell, what with such casual arrangements and the complete lack of communications. (Imagine the stress of an African safari without mobile phone apps and live updates to Instagram and Facebook 😉 )

The picnic spots in the park were unfenced, despite repeated warnings to the Board by warden Stevenson-Hamilton about the dangers involved. It was finally agreed that picnic spots would not be shown on tourist maps, and that warning signs would be put up.

By 1930, things were getting out of hand, and a few more rules were required to maintain order. Consequently, an official list of rules and regulations was drawn up. But with no funding to conduct patrols, they were rarely enforced.

THE TROUBLESOME BOARD

The historical evidence that exists on Kruger frequently mentions the epic fights that were had with the Board at the time, an assemblage of stooge-like characters. And, while curbing infrastructure in the name of conservation is a worthy cause, the Board didn’t seem to be committed to any particular ethical stance. Instead, they seemed to possess a staunch commitment to the slow turning wheels of bureaucracy.

One notable dispute took place over baths. A proposal was made that the camps had to be equipped with hot water, but the chairperson, Senator Jack Brebner, considered this a foolish luxury. The fight continued, and in 1933 hot water was granted on the condition that each guest paid a shilling per bath.

Being generally out of touch, the Board had to be convinced that the game rangers could not be expected to make the beds and bring the guests tea, while also trying to make sure the buffalo don’t go thundering through a neighbouring farm. Finally, much to everyone’s relief, no doubt, the Board agreed to hire more staff.

PLANES, TRAINS AND CARS

Tourists in Kruger during the early days faced unique challenges, including the almost total lack of roads. Before 1928, there were only service roads, capable of low-volume traffic from Gravelotte and Acornhoek to the Portuguese border (modern-day border of Mozambique). The roads were not capable of carrying heavy tourist traffic.

In 1922, South African Railways offered tours via trains, and for a brief moment in history, air service was introduced, and then promptly cancelled. There were seven planes, of which six were legal, and they seated just two or three passengers at a time.

While there was a functioning airstrip at Mavumbye (near Satara), there was still the challenge of getting the guests from the airfield to the rest huts. In the 1940s the first official roads were built. There were several notable challenges to this construction process, including the thick vegetation that renders vast areas of the Lowveld reasonably inaccessible. Add to that challenge the shortage of finances and lack of manpower, and the situation became rather dire.

The Board dealt with these challenges by having the already overworked and underfunded game rangers help to clear the thick vegetation and make the roads.

This once again shows that a Kruger Park ranger’s remarkable forbearance and grit is never in question – then and now.

Eventually the full network of roads we know today appeared, and in the 1960s some of the roads were tarred. One has to wonder if we lost a bit of the ‘old’ Kruger when some of the dirt tracks were covered up. Stevenson-Hamilton most likely would have thought so.

THE ‘GREATER KRUGER’

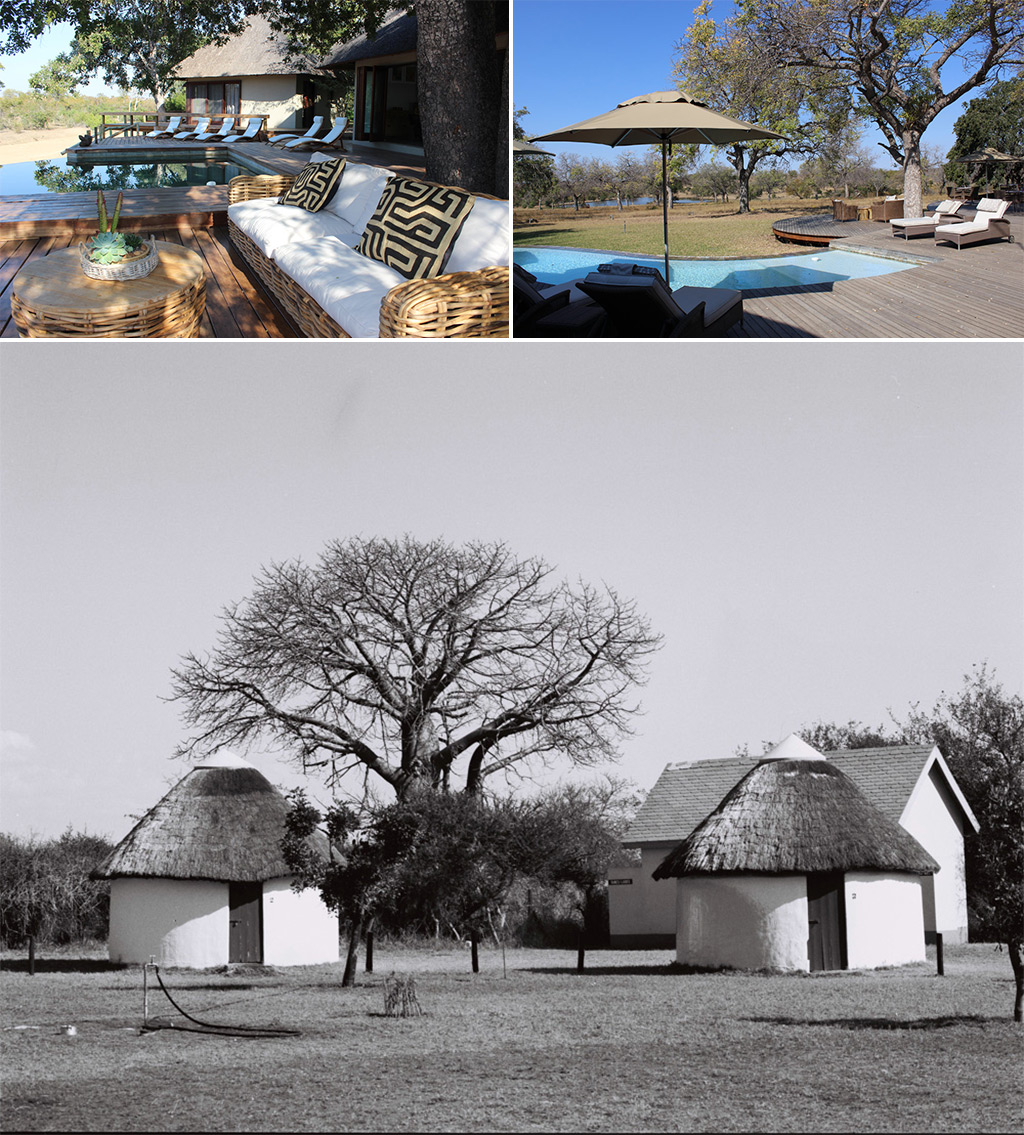

The 344,000 ha Greater Kruger is one of conservation’s biggest success stories, in that land outside the national park is incorporated into an overriding management strategy. Additional parcels of land (privately and community-owned) on the western border have been incorporated into the core protected area over the years, by the signing of management accords and the removal of fences. This ongoing process involves complex negotiations and varied land-use requirements and expectations, including photographic tourism rights and trophy hunting in some areas (there is no trophy hunting in the national park itself).

There are no longer fences between these reserves and Kruger, providing the animals with an opportunity to roam, thereby reducing pressure on vegetation and bringing back historical local seasonal wildlife movements in an east-west direction, compared to the north-south shape of the Kruger National Park.

Read more about the Greater Kruger and the related estimated economic benefits

Sabi Sand Reserve

The 65,000 ha Sabi Sand Reserve shares a 50km unfenced boundary with the Kruger National Park. When the Kruger National Park was declared in 1926, the original landowners of the Sabi Game Reserve were excised and had to settle for land outside of the national park. In 1948, 14 of these conservation-minded landowners met at Mala Mala and decided to join forces and create the first-ever private nature reserve in South Africa. The eastern fence of the reserve, bordering the Kruger National Park, was removed in 1993, making the Sabi Sand Reserve part of the Greater Kruger. Land use is for photographic tourism and private leisure use.

Associated Private Nature Reserves (APNR)

The 197,885 ha APNR is an association of privately-owned reserves that removed fences with the Kruger National Park in 1993 after operating before that as wildlife hunting and livestock farms. The reserves (which in turn are made up of multiple smaller properties) included in the APNR are Timbavati Private Nature Reserve (53,395 ha), Klaserie Private Nature Reserve (60,080 ha), Umbabat Private Nature Reserve (17,910 ha), Balule Nature Reserve (55,000 ha) and Thornybush Game Reserve (11,500 ha). Land use varies from private leisure use to photographic tourism and trophy hunting on some properties.

Manyeleti

Founded in 1963, the 23,000 ha Manyeleti Game Reserve is sandwiched between the Kruger, Sabi Sand, and Timbavati, with no fences in-between. It also has an interesting and unique history. During the Apartheid years, it was the only reserve that welcomed people of colour, and after claiming back the land, the local Mnisi people now own and manage the reserve. Land use is exclusively for photographic tourism.

Letaba Ranch

The 42,000 ha Letaba Ranch Game Reserve, just north of the mining town of Phalaborwa, shares an unfenced border with the Kruger National Park. The reserve is owned by the local Mthimkhulu community and has historically been used mainly for trophy hunting. Future plans include hunting and eco-tourism, but current operations appear to be in a state of turmoil.

Makuya

Makuya Nature Reserve is a 16,000 ha game reserve near the Pafuri gate in the far north of the Kruger, and also shares an unfenced border with the Kruger National Park. The reserve is owned by the Makuya, Mutele, and Mphaphuli communities and is used for both trophy hunting and photographic tourism purposes.

BEYOND SOUTH AFRICA AND THE BIG PICTURE

Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park (GLTP)

GLTP is a 3,8 million-hectare peace park, created on 10 November 2010, that straddles the international borders of three countries, with some of the best wildlife areas in southern Africa being managed as an integrated unit.

This transfrontier park links the Greater Kruger National Park in South Africa to Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park (1 million ha), and Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park (500,000 ha). Fences between the parks have started to come down, allowing the animals to take up their old migratory routes that were previously blocked by political boundaries. Translocations of various antelope species and entire elephant breeding herds have been undertaken, to speed up the process.

Transfrontier Conservation Areas (TFCA)

The TFCA is a strategy to expand the GLTP to an area of approximately 10 million hectares, by incorporating several more national parks, such as Mozambique’s Zinave National Park (400,000 ha) and Banhine National Park (725,000 ha), plus large tracts of state and community-owned tracts of land in-between these parks.

The Kruger National Park is the foundation and role model for this growing and evolving conservation success story. For more about big-picture plans, read Kruger 10-year Management Plan.

WIND BACK THE CLOCK: PRE-KRUGER TIMES

People have lived in and travelled through Kruger for thousands of years.

The Kruger is an archaeologist’s treasure trove, with more than 300 significant sites – from early Stone Age to San rock art – and cultural artefacts from thousands of years ago. The humans of history have left their mark on the Kruger National Park of today.

Before Kruger’s formalisation as a protected area, the area was home to people who mined, hunted, traded and lived their lives – as humans do. The ruins of Thulamela on the southern banks of the Luvuvhu River near Pafuri is one of the most significant archaeological finds in South Africa. This ancient stone citadel reveals a thriving historical mountain kingdom that was occupied by 3,000 people who traded in gold and ivory between 1200 and 1600 AD. The prolific trading community, descendants of the Great Zimbabwe civilisation, were skilled goldsmiths who also traded in iron extracted and smelted from 200 local mines. After the Thulamela dynasty a Tsonga-speaking agricultural and fishing community, known as the Makuleke, settled in the area and thrived until they were forcibly removed to make way for the national park.

The transition to conservation status heralded a less pleasant part of Kruger’s history, when these indigenous people were removed from the area, and relocated elsewhere. In recognition of this, and in line with South Africa’s ongoing land restitution process, in 1998 the Makuleke area in the Kruger was returned to the ownership of the Tsonga people, who now earn concession royalties in return for that area remaining within the Kruger National Park. Other areas within and bordering the Greater Kruger are currently under some form of land claim, and the future will reveal the results of this process.

Although there are no longer any indigenous people living inside the Kruger, there are still many interesting conversations to be had, across Africa, about indigenous people living semi-traditional lives within the boundaries of national parks and other protected areas.

These and other issues such as poaching continue to drive the evolution of this fantastic, iconic national park. The Kruger is one of the world’s most outstanding conservation success stories, with a fascinating past and promising future. Long may it continue to evolve and thrive!

Find out about Greater Kruger or Kruger National Park for your next African safari. We have ready-made safaris to choose from, or ask us to build one just for you.

Find out about Greater Kruger or Kruger National Park for your next African safari. We have ready-made safaris to choose from, or ask us to build one just for you.

We wish to thank South African National Parks (SANParks) and Joep Stevens, their General Manager Strategic Tourism Services, for sharing their numerous resources, including photographs and text, from their archives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Noelle Oosthuizen

Growing up watching Beverly and Dereck Joubert’s documentaries and idolising Jane Goodall, Noelle Oosthuizen has always dreamed of living in the bush. For now, she writes about her bush adventures from her home in Cape Town, South Africa. She has a particular soft spot for chacma baboons, and she advocates for these charming primates every chance she gets. By far her favourite adventure has been being a foster mom to an orphan baby baboon.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()