EDITOR’S COMMENT: On Saturday, the 13th of May 2023, six lions were speared to death by angry local residents inside the headquarters of Big Life Foundation – a non-governmental organisation dedicated to protecting the wildlife in Kenya’s Greater Amboseli Ecosystem through a community-based collaborative approach. The retaliatory killings came after the lions killed 12 goats and a dog near Mbirikani town the night before.

In response to Africa Geographic’s coverage of the incident in our weekly newsletter, representatives from Big Life Foundation requested us to publish their transparent account of events. In the following editorial, Big Life CEO, Dr Benson Ntoyian Leyian, explains how the lions came to be killed, the challenge of reducing human-wildlife conflict and the complexities of the issues at play.

No one wants to wake up with a lion in their home. I know because it has happened to me.

I have had lions break into my boma (a Swahili word for an enclosure protecting animals and people). I’ve had them kill my livestock. I’ve felt the resultant anger. I’ve participated in a retaliatory lion hunt.

That was long ago. Today I am the CEO of Big Life Foundation (Big Life), a community conservation organisation based in the Greater Amboseli Ecosystem of southern Kenya. Humans and nature are inseparable here, and we implement a range of conservation programs designed to meet the needs of both.

But I still have livestock, lions still kill them, and I still get angry.

On the 13th of May 2023, we witnessed an appalling expression of this type of anger in the form of a crowd that speared six lions to death on a community ranch between the Amboseli and Chyulu Hills National Parks.

A pride of nine lions had entered a boma overnight and killed 12 goats and a dog. They were in an area of dense human settlement, and after being chased from the boma, the lions retreated to the nearest patch of thick bush they could find, which happened to be a revegetation site within Big Life’s fenced headquarters. Big Life community rangers could move some of them out that night, but six remained inside at daybreak.

The Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) and local community leaders soon arrived to meet with Big Life’s senior staff, and the decision was made to leave the lions in the compound. The intention was to wait until the arrival of a vet to assess the potential for translocation. All was calm, and staff from KWS and the Kenya Police Service were on site in case that changed.

News of lions in town travelled quickly, and a crowd soon began to swell, including the irate owner of the livestock killed the night before. The tension was building with each new arrival until, eventually, the collective control snapped. The crowd of about eighty men, most armed with spears, broke through the fence to go after the lions.

Some of the rangers standing in the way were armed, but any gunfire or use of force would have quickly escalated the violence and likely resulted in human injuries or deaths. The rangers stood down, and despite what followed, we believe this decision was the right one.

By the time the dust had settled, all six lions were dead.

The staff of Big Life are all shaken, and my intention in writing this piece is not to diminish the significance of what happened or to try and explain it away. Those of us working at the interface between humans and wild animals need to be honest and self-critical to progress. Big Life values transparency and welcomes constructive criticism.

In this editorial, I aim to address emerging suggestions that this incident is symptomatic of larger issues and trends and that community conservation efforts in Amboseli are failing. I want to counter this with some context, partly involving the story of one of Africa’s most extraordinary recoveries of a local lion population.

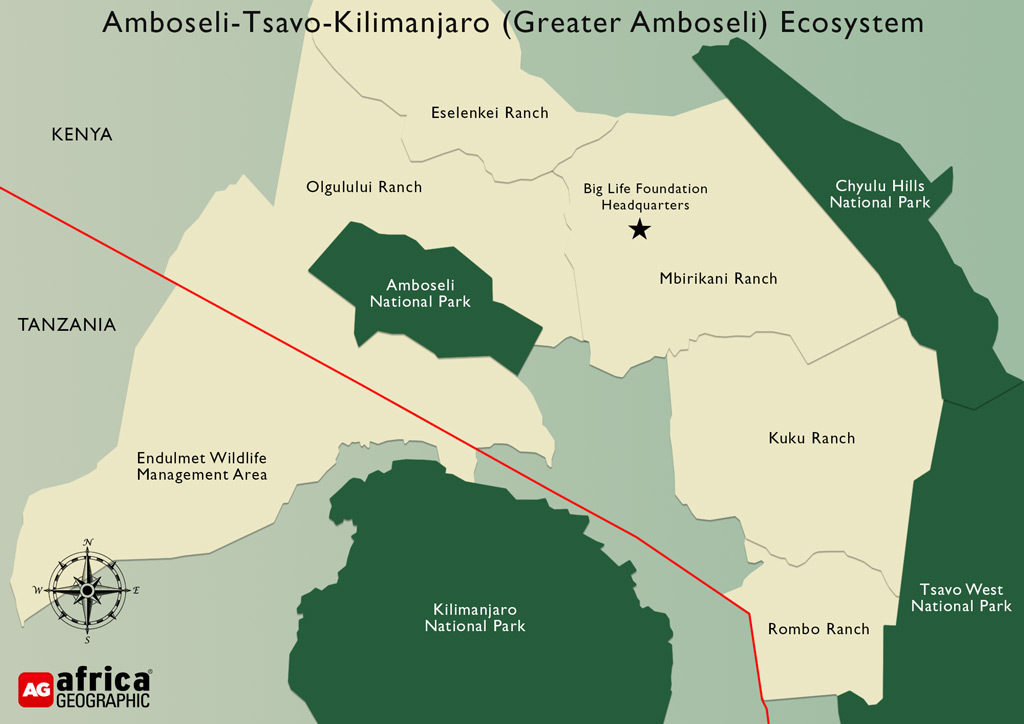

The Greater Amboseli Ecosystem is an area of approximately two million acres (just over 8,000 km2). However, only a fraction of that (around 5%) is protected by National Parks, with Amboseli National Park perhaps being the most famous. There are few fences, and many wild animals, including species such as elephants and lions, spend most of their time on Maasai community-owned lands outside of these formally protected areas.

As a result, conflict between predators and livestock has always been a part of life here. This conflict reached its zenith in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when irate livestock owners, aided by the emergence of poisons like Carbofuran (a carbamate pesticide), drove the Amboseli lion population to near extinction. At least 108 lions were killed between 2001 and April 2006, and while no one knows for sure, the population is believed to have dipped as low as 15-20 individuals in the entire ecosystem.

In response, Big Life and the leaders of the 330,000-acre (1,335km2) Mbirikani Group Ranch came up with the Predator Compensation Fund (PCF) in 2003. The idea of compensation for livestock losses was not new, but the innovative design of this program definitely was.

When a livestock animal is killed by a wild predator, Big Life sends a verification team to the site by motorbike within 24 hours. Evidence is gathered to determine what predator was responsible and what the circumstances were (including whether there was negligence on the part of the herder). The compensation figure payable depends on several such factors, and the livestock owner is issued with a ‘credit note’.

Every two months, these credit notes are redeemed at a PCF payout. That is Big Life’s commitment. However, the community has also made a commitment, which is not to kill predators or face stiff penalties if someone does. If anyone does kill a lion (or any predator), all credit notes for that area are invalidated. Anyone who was owed money doesn’t get it, and any lion killer faces the collective wrath of their community. In addition, the killers must pay a fine of seven cows for each lion killed, a hefty penalty in Maasailand.

With an extensive network of community rangers and undercover informants, almost no predator deaths go unnoticed, and the agreement can be enforced.

Almost overnight, the lion killings stopped. In the one and a half years before the Predator Compensation Fund launched, at least 31 lions were killed on Mbirikani Ranch. By comparison, in the twenty intervening years (prior to this recent incident), only 13 lost their lives to conflict with farmers. That’s a 97% reduction in lion killing. Since 2003, Big Life has compensated the loss of 48,648 livestock to wild predators (the majority were sheep and goats killed by spotted hyenas) across the area covered by PCF (currently 550,000 acres – 2,226 km2). It is an astonishing number, particularly compared to how few predators have been killed in retaliation.

PCF has not been solely responsible for the steep reduction in lion killing: many organisations and interventions have contributed, including Lion Guardians and the Born Free Foundation. However, the ‘available-to-all’ principle of PCF has made it the furthest reaching, and we believe it has been at the core of the behaviour change and increased tolerance of wild predators.

The lions have done the rest. Lion Guardians have identified at least 250 individual lions in the ecosystem today. That’s equivalent to a six-fold increase in lion density. It’s a stunning turnaround, and all the more remarkable that it has been achieved on community-owned land outside of a national park or reserve.

And that’s just one piece of good news from Amboseli; the story is similar for other species. In 1978 the elephant population of the ecosystem was approximately 700; today, it is 2,000. Community participation in conservation efforts has been fundamental to these successes, and this participation was recently affirmed when the collective landowners of a million acres (over 4,000 km2) agreed to set aside 31% of their land for conservation areas.

What comes next is always difficult in a situation like this, particularly when attributing blame among a large group of people involved in a chaotic incident. Compensation payments are stopped as per the PCF agreement, but given the severity of this incident, Big Life has stopped funding for all community programs in Mbirikani. Following meetings with the community leaders, it has been agreed that this will remain the case until such time that the main participants in the killings have been identified. In addition to paying the fine that will total 42 cows (seven cows for each of the six lions), all those involved will be disqualified from receiving conservation-related benefits, including scholarships or employment. Whether the culprits will be prosecuted is yet to be decided and is a decision that will be made by the relevant government authorities.

Community conservation efforts are seldom linear. There are steps forward and steps back, and we must learn from both. Co-existence is challenging, but in Amboseli, Big Life is showing that humans and wildlife can share space when conservation programs are designed with the needs of wildlife AND people in mind.

Further context and reading:

The Amboseli-Tsavo-Kilimanjaro ecosystem (or Greater Amboseli ecosystem) in Kenya and Tanzania is one of the most iconic of Africa’s wilderness areas. It encompasses five world-famous national parks: Amboseli, Chyulu Hills, Tsavo East and West, and Mount Kilimanjaro. These parks are unfenced, allowing for habitat connectivity and wildlife movement. However, the Group Ranches between them encompass areas of rural agriculture, homesteads and villages with high potential for human-wildlife conflict.

For more information on the Amboseli Ecosystem, see our article on Amboseli National Park

To learn more about human-elephant conflict in Amboseli, Josh Clay of Big Life Foundation explains the situation in Maasai, Maize & Mammoths

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()