DISCO DONKEYS

![]()

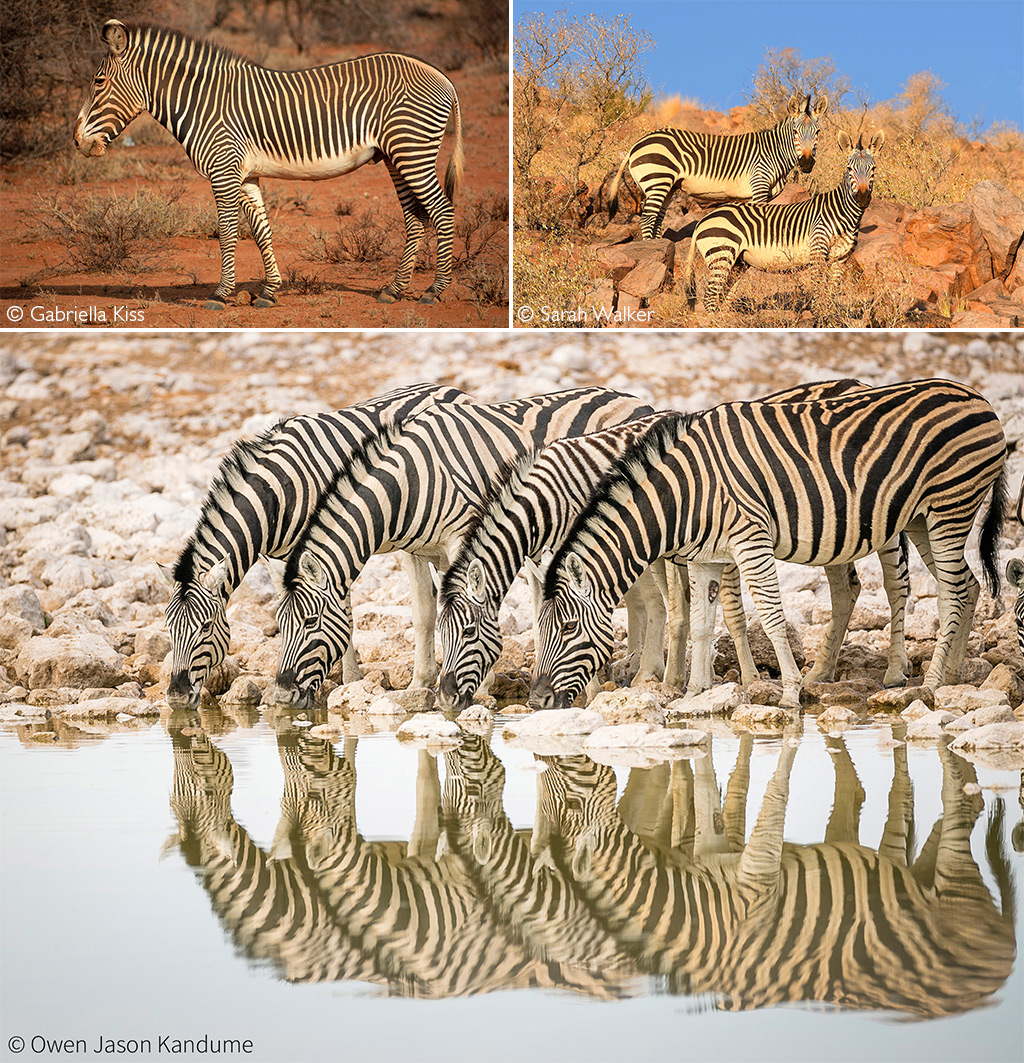

With their dazzling black and white stripes and familiar horse body language, zebras are a firm favourite among safari-goers, especially when seen in their thousands during migratory events.

As the dust settles on the first zebra sighting, someone is bound to ask “So, are they white with black stripes or black with white stripes?”, at which point their guide usually forces a laugh and thinks seriously about their father’s advice to pursue a financial career in a big city.

The word “zebra” is borrowed from either Italian or Portuguese, where the first vowel is pronounced as a long vowel. And locally, guides have been heard referring to them as “stripy ponies, “horses in pyjamas” or, in the words of one safari guide in Tanzania, “disco donkeys”.

What follows is a celebration of one of the most unique, iconic and fascinating African animals. By the way, they are technically grey-skinned with black and white stripes.

The three species

There are three recognized species of zebra: the plains zebra (Equus quagga), the mountain zebra (Equus zebra) and the Grévy’s zebra (Equus grevyi), all belonging to the Equus genus, along with horses, donkeys and asses.

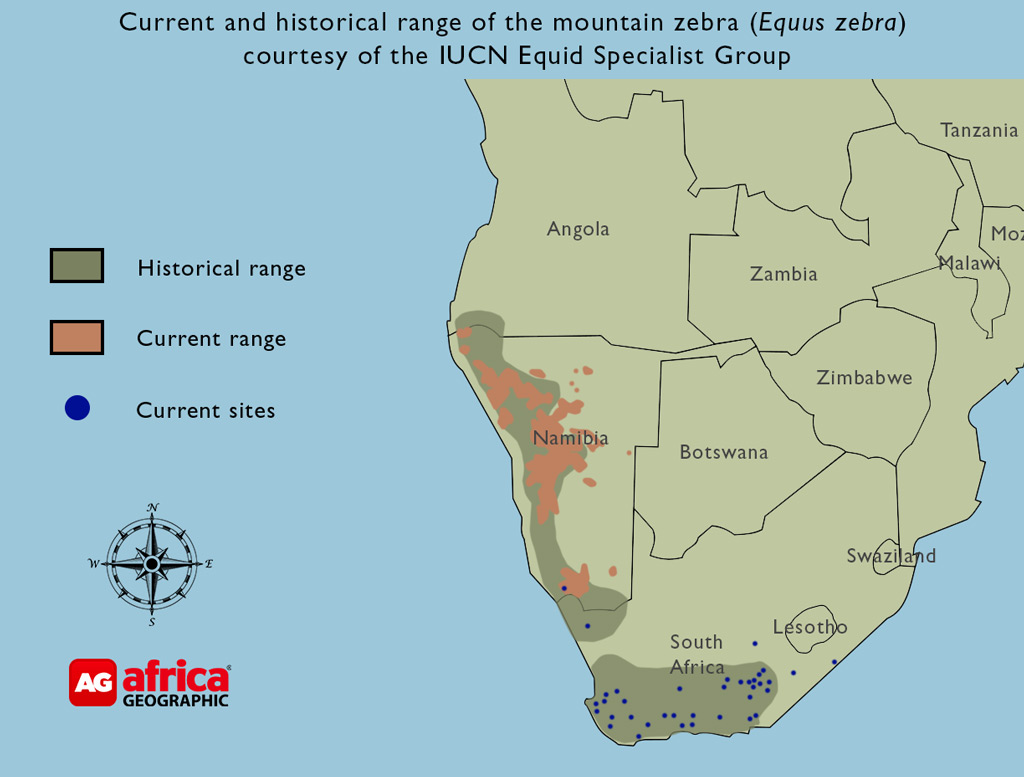

The mountain zebra: There are two recognized subspecies of mountain zebra – the Cape mountain zebra and the Hartmann’s mountain zebra, both of which are listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. Both subspecies have a distinctive dewlap and bold strip patters that extend down the lower leg to the hoof but not around the middle of the belly. The Cape mountain zebras were very nearly extinct, with numbers recovering from 80 individuals in the 1950s to the estimated 4,790 individuals alive today, found mainly in the Mountain Zebra National Park. The vast majority of Africa’s Hartmann’s mountain zebras are found in Namibia, and there are believed to be around 33,000 of them left in the wild.

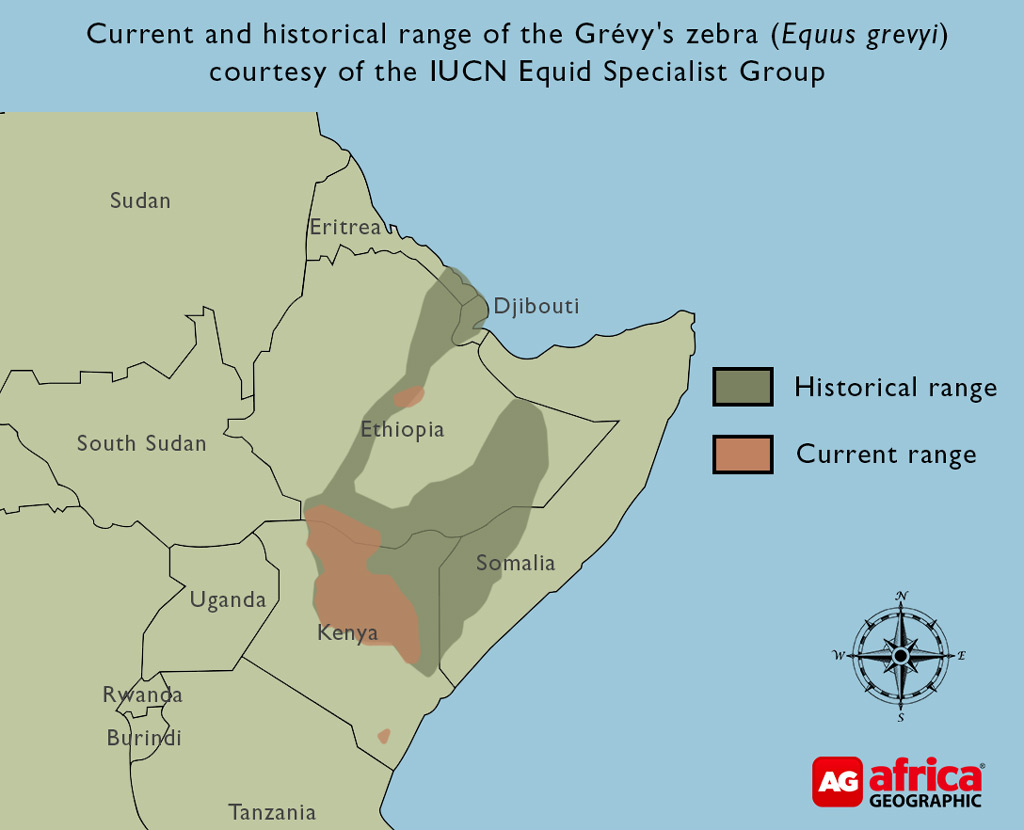

The Grévy’s zebra: The largest of the zebra subspecies is also the most threatened of the three and their populations are currently isolated to central and northern Kenya, with a minimal number in Ethiopia. Currently classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List, there are fewer than 3,000 mature individuals left in the wild. Their ears are larger than those of the other two species, and their stripes are narrow and close-set, without extending to the belly.

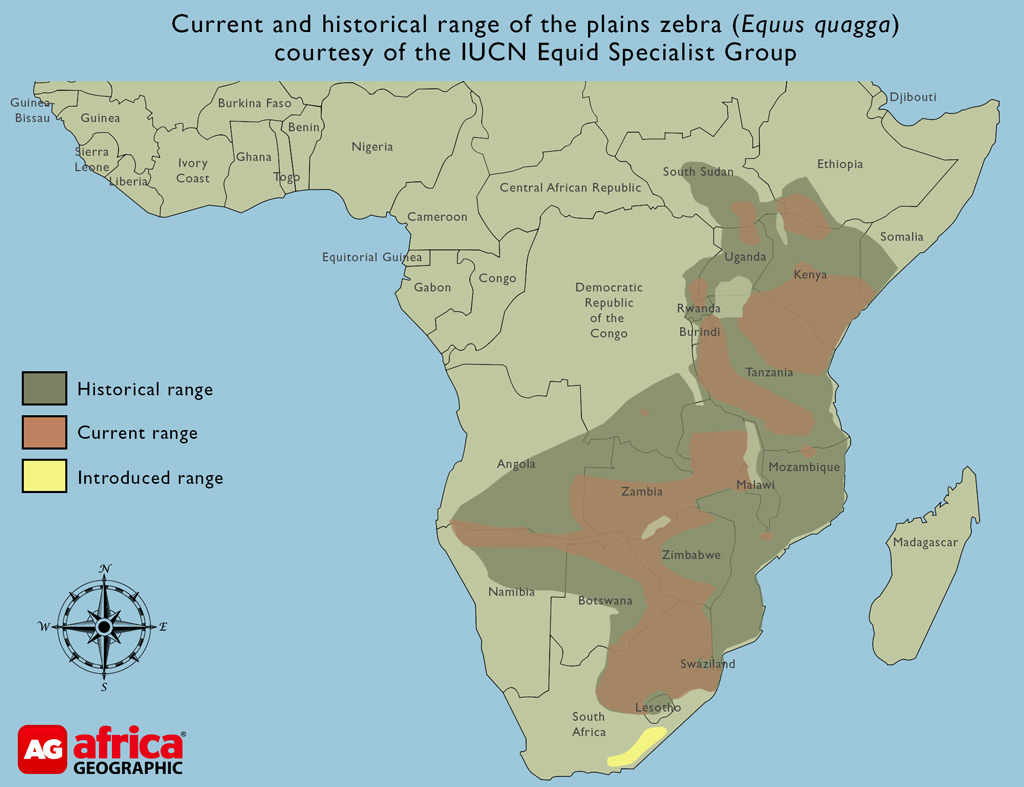

Plains zebra: The plains zebra is by far the most populous of these species and is the most likely to be encountered on safari. The easiest way to distinguish them from the other two species is the stripes on the stomach – in plains zebras, these reach to the centre, but in the other two species, they don’t extend that far, and their bellies are white. The stripes of plains zebras also tend to fade towards the lower leg. At present, while there is some disagreement, there are six different subspecies, and some (but not all) have “shadow stripes”, pale, thin stripes in between their bold black stripes on the rump and sides. As the most populous of the three species, the below information will deal mostly with plains zebra, though there are numerous shared similarities between the three species.

Plains zebra quick facts:

- Social structure: a harem with a dominant stallion, around 2-8 mares and associated offspring, or bachelor herd.

- Mass: 175-320kg

- Shoulder height: 127-140cm

- Gestation period: 12 months

- Number of young: 1 foal (2 have never been recorded)

- Average life expectancy: Over 20 years in the wild, up to 40 years in captivity

Currently classified as ‘near threatened’, there are believed to be around 600,000 plains zebra in Africa, all in sub-Saharan Africa. They are water-dependent and tend to prefer grasslands and sparse woodlands and are generally not found in deserts or rainforests. As bulk grazers, they tend to be less fussy about the grass species or parts of the grass they eat, and they consume approximately double the amount of food as a ruminant of comparable weight (such as a wildebeest), which they process twice as fast. For this reason, they are known as “pioneer” feeders, hence why they tend to be the forerunners during the Serengeti/Maasai Mara ecosystem Great Migration.

Taxonomy and the quagga

Up until relatively recently, the scientific name of the plains zebra was Equus burchelli, but this was changed to Equus quagga when genetic studies revealed that the extinct quagga was, in fact, a subspecies of the plains zebra. The quagga, hunted to extinction towards the end of the 19th century, had zebra-like colouration on the front half of its body but uniform brown colouring towards the rump and legs. “Quagga” comes from the Khoikhoi name for zebra and is an onomatopoeic name resembling the sound that all zebras make, described as “kwa-ha-ha”. The Quagga Project based in Cape Town is currently attempting to selectively breed plains zebra to “recreate” the quagga.

Herd mentality

The harem structure follows a basic formula of a dominant stallion along with several mares and their most recent offspring. When a young female reaches sexual maturity at around 2.5 years old, she attracts the attentions of other stallions who may compete with the dominant stallion and, ultimately, steal her away to add to, or even begin, their own harem. Zebra skirmishes are frequent, and a serious zebra fight can be deadly. Their kicks are tremendously powerful, and the males have erupted canine teeth that they use to bite their opponents – broken skin and bones are not uncommon, and many a zebra have lost their tail as a result of a fight. Occasionally, a stallion that has taken over an entire herd may kill the foals sired by the previous male.

There is a set dominance hierarchy within the females of the harem, starting with the mare that has been with the stallion the longest. Initially, a new mare to a harem is tormented by the other females, who take time to accept her presence, and the stallion often has to intervene on her behalf. Young males generally leave their herds and join bachelor groups with other young males. These herds also have their own dominance hierarchy, and it here that the young male can practice the fighting skills necessary to one day compete for a female once he reaches sexual maturity at around 5-6 years old.

Naturally, zebras are often seen in much larger groups than the ones described above, especially those that are migratory – such as in Tanzania, Kenya and Botswana. These harems and bachelor groups regularly associate with other groups, often interacting with each other with limited amounts of acrimony unless competition over a female arises.

A striped mystery

There is considerable debate around the reasons for the zebras’ unique striped coat. The predominant theory at present is that the striped pattern interferes with the vision of tsetse flies and other biting insects, preventing most from landing on a zebra’s coat. There are, however, other theories that have been put forward as to why zebras have stripes. Some zoologists favour the thermoregulation argument; the idea being that the black stripes heat up more than the white areas on the zebra which in turn creates microcurrents of air movement which cool the sweating zebras more rapidly. Others suggest that the unique stripe patterns may be a way for zebras to recognize other zebras.

The idea that zebras are striped as a kind of camouflage or anti-predation mechanism still holds some sway with certain biologists, who are seeking ways to test how lions respond to striped vs unstriped prey. The explanation behind this is not just that the stripes disrupt the outline of the zebras but that when multiple zebras are moving together, the stripes create an optical illusion that distorts the perception of the direction of movement. Given that most predators have exceptional hearing and that many a hunting lion has been observed picking out a specific zebra as a target without any undue difficulty, there are strong arguments against this particular line of thinking.

There is also, naturally, no reason why it might not be a combination of factors that led the zebras’ ancestors to develop a striped coat.

No discussion of zebra stripes would be complete without mentioning Tira, the zebra foal that caused an internet sensation after it was photographed in the Maasai Mara in 2019. Tira exhibits a kind of pseudomelanism that has resulted in an almost entirely black coat with white polka dots. This foal is not the first of its kind, however; dark-coloured zebra foals have been photographed in Botswana. There are also cases of leucistic zebra in the wild, though these are more commonly seen in captivity.

Final word

While the black and white stripes set zebras apart from other large mammals, their striking beauty belies their hardiness and resilience, characteristics that define the true essence of a wild zebra. They are capable of bearing the pain of horrific injuries, broken bones and torn skin with a profound survival instinct and, if unfortunate enough to be on the receiving end of a predator’s attention, will fight until their very last breath. The stallions are fierce defenders of their small families and often risk their own lives in defence of their foals.

Like many of their equid cousins, they do occasionally demonstrate a propensity for irascible temperaments but, given the harsh realities of living wild, this stubborn streak serves them well.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()