In recent years, studies have shown that riverine rabbits frequent areas far outside of the riverine habitats thought to be their main domain. But why has it taken so long to discover additional populations outside of the riverine habitats of the Nama-Karoo? What technologies have helped study their behaviour, and how can new methods of study impact conservation of the species? Christy Bragg explains how methods of gathering significant information about the species has changed over the years.

Riverine rabbits. With a name like that, one would expect these creatures to live near rivers, and up until a few years ago, they were indeed considered to be riverine-habitat specialists. This species was believed to be restricted to the shrubby alluvial floodplains of the rivers in the Nama-Karoo in South Africa. But then, someone pulled the rabbit out of the hat: a riverine rabbit was spotted in renosterveld vegetation (a vegetation type of the Cape Floristic Region), in the southern Cape, on a hillslope. It has since been spotted in many other habitat types, including succulent-Karoo plains in the southern Cape. Indeed, its scientific name, Bunolagus monticularis, gives us a clue about the different places it likes to live. “Monticularis” means mountainous. And these rabbits have since been found to frequent mountainous areas – and not just flat river plains.

What do we know about the riverine rabbit?

But what has caused the delay in discovering populations outside of the riverine areas of the Nama-Karoo? Firstly, the riverine rabbit is not easy to study. They are nocturnal, shy and, in the dark, resemble hares (such as the scrub hare and Cape hare). Secondly, studies done in the Nama-Karoo in the 1980s showed that the population might be declining due to the conversion of natural riverine habitat to agricultural lands. And thirdly, because they were not expected to be found outside the Karoo floodplains; searches for them outside this habitat have been limited.

Despite this, they have been recorded in the Touws River region in the southern Cape. Subsequently, they have been spotted in and around Anysberg Nature Reserve, a provincial reserve near Laingsburg (also in the southern Cape), and near Baviaanskloof in the Eastern Cape. Rabbit roadkill later alerted the conservation authorities to the presence of riverine rabbits near Uniondale, also in the southern Cape. Today, there’s another way to detect riverine rabbits: camera traps have significantly contributed to our understanding of this species’ ecology and distribution in recent years.

Surveying sensitive species

Through camera trap surveillance, the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), has bolstered conservation efforts for the critically endangered riverine rabbit – having positioned at least a hundred camera traps in varying habitats to monitor the rabbits.

Before using camera traps, surveys for riverine rabbits were an intensive undertaking, where ten or more humans would walk through the habitat over several days, shouting and calling, hoping to flush a rabbit. But one camera trap in the hand is worth ten humans in the bush because a camera trap works 24/7. Now, using motion detection, these cameras are triggered to capture images of the rabbits in various habitats – providing invaluable insight into their secret lives.

Camera traps are the quiet, accurate observers in the habitat, scanning far more significant areas over more extended periods than walking-line surveys could ever accomplish.

Several camera trap studies have shown that the riverine rabbit is crepuscular, not purely nocturnal. This means they are more active during the dawn (early mornings) and dusk (late evenings). Some preliminary research also showed that rabbits and hares do not share habitat. This whet the interest of Dr Zoe Woodgate, from the University of Cape Town, who completed her doctorate on this fascinating rabbit. Woodgate wanted to know more about what determines the more peculiar habitat choices of the riverine rabbit, so she conducted her fieldwork in the Sanbona Wildlife Reserve, a private game reserve in the Western Cape.

Woodgate set up 150 cameras in 30 sites across the southern half of the reserve. This included setting up clusters of five cameras at each of the 30 sites to maximise detection of the species. Each group was spread over 15ha, and cameras were left out in the field for 45 days. She also measured some environmental factors, such as terrain ruggedness, site degradation (due to agricultural activities before the establishment of the reserve), and how close to drainage lines the rabbits occurred.

The results were intriguing. Firstly, she found that the territories of rabbits and hares did not overlap at all. Both hares and riverine rabbits had similar activity patterns, but although they were out and about at the same time of night, they did not live in the same places – likely due to the fact that they competed with one another.

The data also showed that the riverine rabbits were not closely associated with rivers. Woodgate’s model showed that rabbits are more affected by the presence of their competitors, the hares, than by rivers. She also noted that hares would choose living in less suitable terrain over sharing habitat with rabbits. Both hares and rabbits prefer level, rolling plains, but hares would choose less preferable terrain in areas where they co-occurred with rabbits. But what can be concluded from this? Do rabbits displace hares, or do hares outcompete rabbits?

There are mixed views. Some experts believe the hares are bigger and nastier and perhaps ‘bully’ rabbits out of their habitat. Some believe rabbits are the quiet kings of their habitat and displace hares to less preferable habitats. Only time and more research will tell.

Cameras, riverine rabbit conservation and wind farms

Camera traps are a critical component in the conservation toolbox. By setting up camera traps in more ‘unusual’ habitats, several new populations of riverine rabbits have been found, and more are expected to be discovered. Conservationists work with farmers and landowners to protect properties that host riverine rabbits under biodiversity stewardship or custodianship. These stewardships recognise landowners as the custodians of biodiversity on their land. And by protecting species such as riverine rabbits, their habitats are also protected – conserving many other plants and animals.

As South Africa increases its renewable energy supply, wind farm development proliferates in the Karoo. Camera traps have proven extremely useful for detecting whether this species occurs in proposed development areas. If firm evidence (from a camera trap) shows that a riverine rabbit is in the area, adequate mitigation measures can be implemented to protect the rabbit and its habitat. For example, turbines can be located a suitable distance from the rabbit’s habitat, and corridors can be developed to ensure its safe and secure movement through the landscape. However, more research is needed on how this species is affected by renewable energy development. For example, the jury is still out on whether the turbines’ noise impacts rabbit behaviour.

Roll on, riverine rabbit

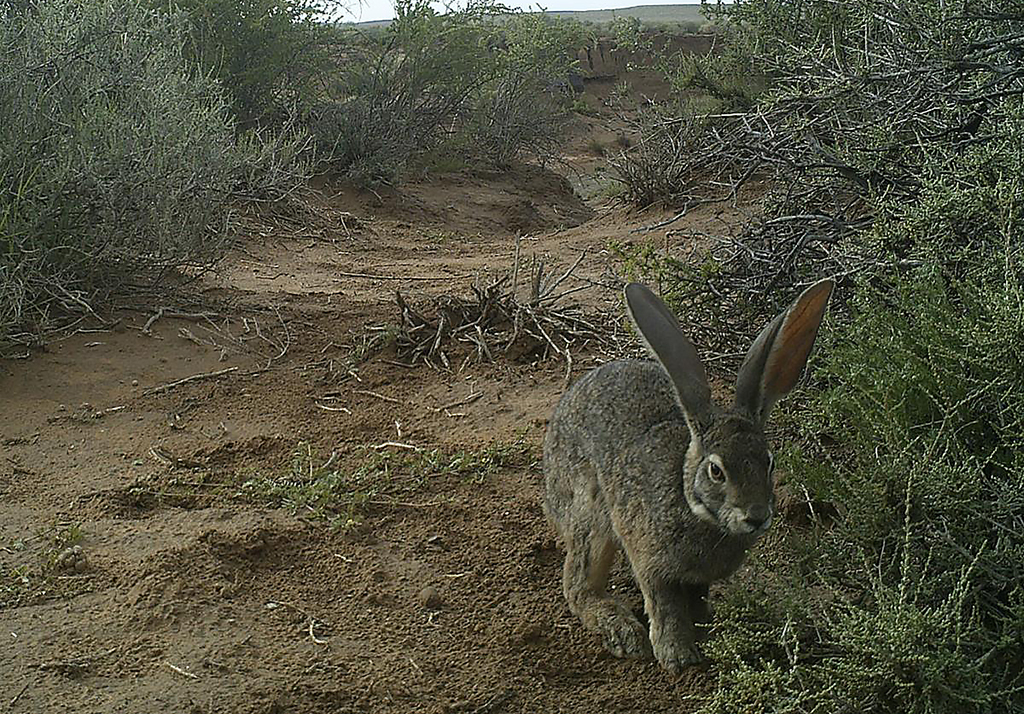

Searching for the riverine rabbit is like a giant Easter bunny hunt, with more and more bunnies being discovered in unexpected hiding places every year. So, if you are ever exploring the rolling hills of the Cape provinces, near Loxton, Sutherland, Montagu, Touws River, Barrydale or even Worcester and Robertson, keep your eyes peeled for this Easter bunny. If you spot a rabbit-like creature, how will you know it’s a riverine rabbit and not a hare? The riverine rabbit has a telltale moustache, a dark black line on its chin, big, satellite-dish ears and hairy bunny-slipper feet. Also, watch for their fluffy tails, resembling a big brown powder puff (whereas the hares have scrawny, black-and-white tails). If you spot one, consider yourself lucky, as they are shy and secretive, and few people have had the privilege of seeing them in the wild.

References

Duthie, A.G. (1989), “Ecology of the Riverine Rabbit Bunolagus monticularis.” MSc dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria.

Woodgate, Z., Distiller, G. and O’Riain, M.J. (2021). “Hare today, gone tomorrow: the role of interspecific competition in shaping riverine rabbit occurrence”. Endangered Species Research, 44 pp. 351-361.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()