Understanding the shaggy-haired scavenger

Steeped in myths and legends regarding magical powers, hermaphroditism and black magic, and more recently cast as villains by Disney, the hyena family undoubtedly suffers from a bad reputation.

With their gentle, social interactions and strong kin bonds rarely witnessed, and their reputation amongst farmers as a livestock predator, the misunderstood and secretive brown hyena currently faces a battle for survival.

Classification

The modern-day Hyaenidae family consists of just four members, although nine species have been recorded from fossils dating to the early Pleistocene period. Currently, each member of the hyena family has its own genus:

• Crocuta (spotted hyena)

• Hyaena (striped hyena)

• Proteles (aardwolf)

• Parahyaena (brown hyena)

Until 1974 the brown hyena (Parahyaena brunnea) was also classed as Hyaena, and there is still dispute regarding its classification.

Phylogenetically, hyenas are most closely related to the Viverridae, a family of small to medium-sized carnivores including civets and genets. Hyaenidae are unique in their ability to crush bone with their specialised anatomy, except for the aardwolf, which is a strict insectivore.

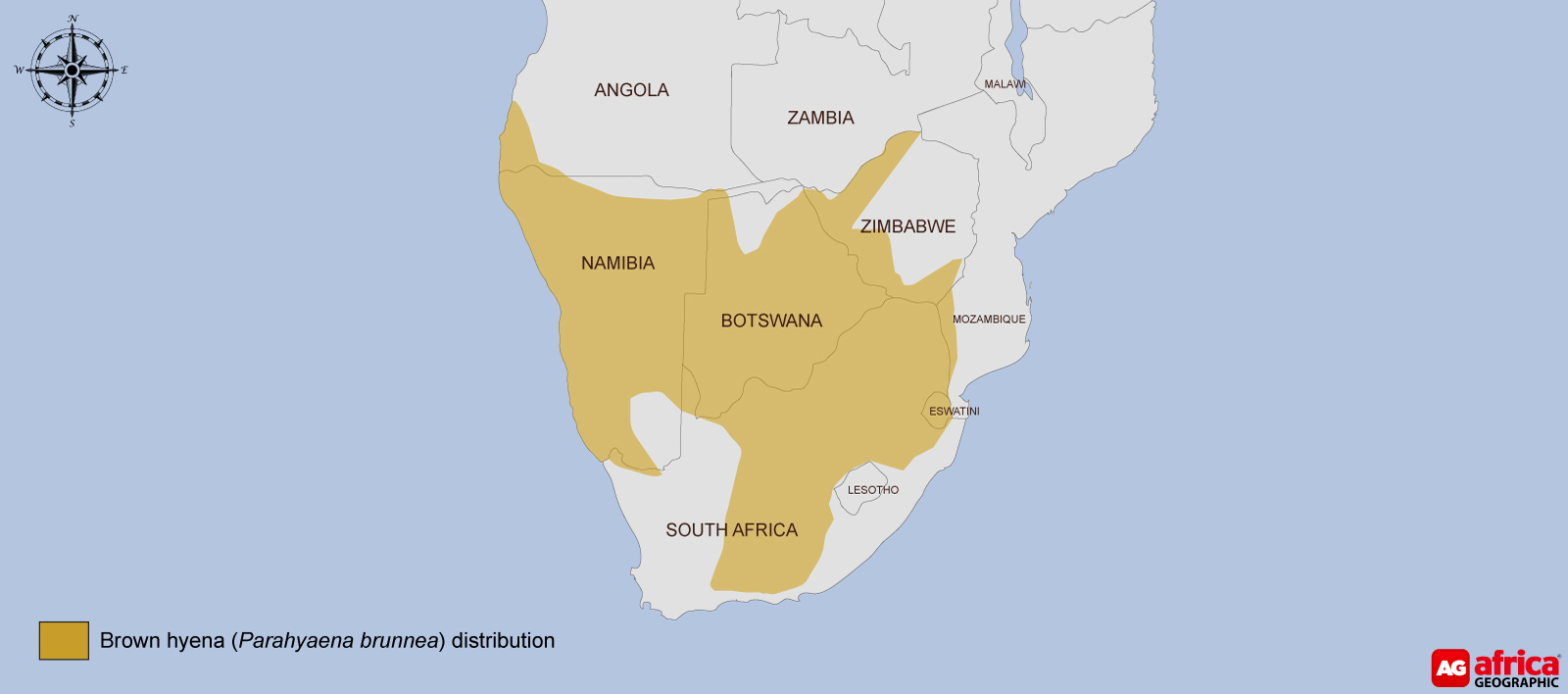

Conservation status and distribution

The most recent figures from the IUCN Red List estimate a population of fewer than 10,000 individuals worldwide, making it the rarest member of the hyena family. The species is currently classed as ‘Near Threatened‘ (a status which means the species may be considered threatened with extinction in the near future), with the population of mature animals experiencing a continuing decline.

Brown hyenas are endemic to southern Africa and occur in South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Angola. Their presence in both Mozambique and Eswatini is currently unconfirmed. It is believed that the largest population exists in Botswana at an estimation of around 4,600 individuals.

More about…

Although most often seen foraging alone, brown hyenas are highly social animals. They live in social groups called clans, the members of which maintain highly intricate relationships. Clan size can range from a single adult female and her offspring to up to 14 individuals. Research from the Kalahari has shown group size to be positively influenced by the quality of food in an area. In contrast, territory size is controlled by the distribution of food resources. Home range sizes have been found to vary considerably across the brown hyena’s range; from 40 km2 in enclosed reserves to over 2,000 km2 in coastal ecosystems.

Brown hyenas are also known as “strandwolves”– an Afrikaans word which directly translates to “beach wolves” in English. This is in reference to the hyena’s habit of taking strolls along the beach in search of food.

Unlike spotted hyenas, there is no significant size difference between male and female brown hyenas; males weigh between 40-44 kg, whereas females weigh around 38-40 kg. The brown hyena is the second-largest member of the family Hyaenidae, surpassed in size only by spotted hyenas.

Clan dynamics

It is believed that brown hyena clans have both an alpha male and alpha female, who share equal status. Females may remain in their natal clan for their entire lives and become breeding adults, whereas most, if not all, males will disperse from their natal clans. It is estimated that 33% of the adult brown hyena population is nomadic, of which the majority are males. These are individuals who do not have a fixed home range or lasting relationships with other brown hyenas.

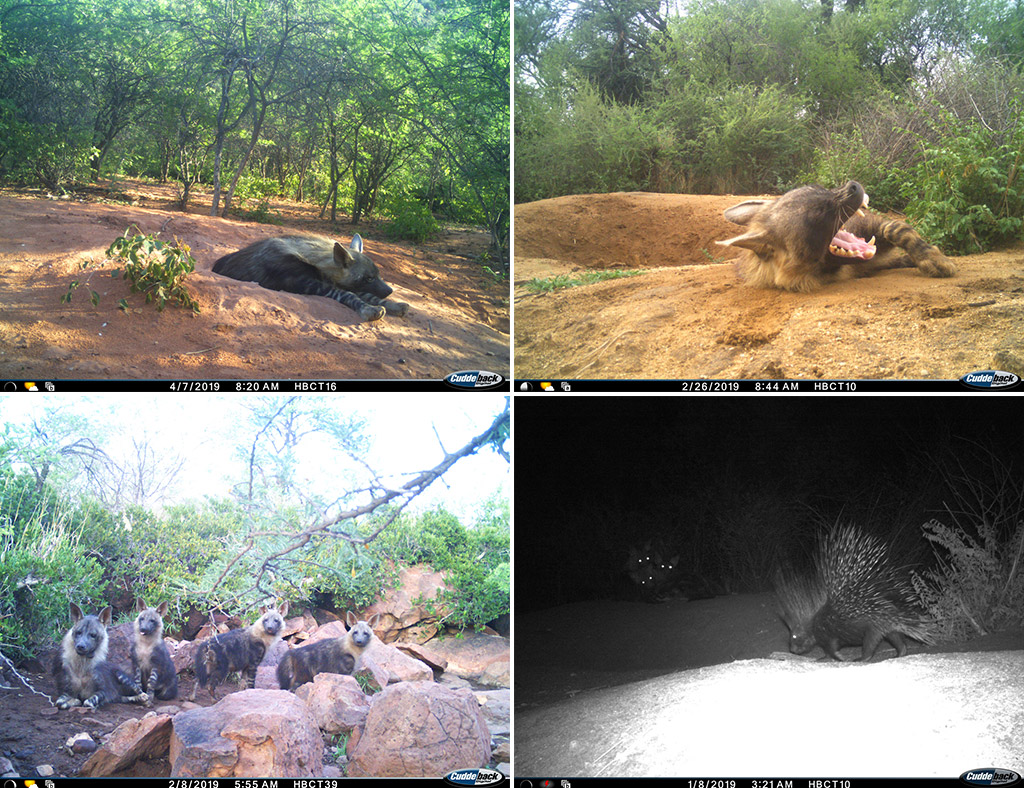

Dens

Dens are the focal point in brown hyena society. The communal den represents a meeting point for clan members to come together to socialise, and also the place where the clan jointly raises the cubs. Old burrows, previously dug by species such as aardvark or warthog, are often used as dens. In more mountainous areas, caves are used.

All clan members will carry food, often over long distances, back to the den for the cubs. As a result, the den burrow is often surrounded by bones, skin and carrion and may attract the attention of other scavengers such as black-backed jackals.

Diet

Brown hyenas are primarily a scavenging species and can walk up to 40 km per night in search of food. They are inefficient predators and food obtained by hunting is rare. In inland areas, their hunting success has been estimated at just 6% of hunting attempts resulting in a kill. Brown hyenas can drive cheetah and even leopard from their kills. They have a highly variable diet, with mammal remains being the most important dietary item.

Insects, reptiles, wild fruits and birds’ eggs are also taken and may help brown hyenas survive in times of low resource abundance. Despite being generalist feeders, they appear to lean towards specific prey items – depending on their habitat. For example, along the Namib Desert coast, brown hyenas hunt Cape fur seal pups during the pupping season and scavenge carrion washed up on the shore.

Reproduction

Brown hyenas have a gestation period of three months, after which they give birth to one to four cubs, with an average litter size of three. Cubs are born away from the communal den, in a small natal den. Unlike spotted hyenas, brown hyena cubs are born with their eyes closed and open them after eight days. At around three months of age, they are brought back to the main den and introduced to the rest of the clan. All adult members of the clan will carry food back to the cubs. Usually, only the alpha female breeds, but if two litters are born in the same clan, the mothers will nurse each other’s cubs.

Brown hyenas have one of the most prolonged suckling periods of any mammal, with cubs taking milk for up to 18 months. They begin eating solid food at around three months of age. By just four months of age, cubs may be left alone for up to 24 hours at a time. Cubs spend the first 12-15 months of their life at the den, after which they start exploring further afield. At 30 months of age, a brown hyena is considered an adult and may disperse from its natal clan to either become nomadic or integrate into a new clan.

Communication

Unlike spotted hyenas, brown hyenas are not vocal and instead use scent as their primary form of communication. They are unique within the hyena family for producing two distinct types of paste marks – a black and a white paste – from a large anal gland. The paste marks are placed mainly on grass stalks, or woody vegetation or rocks in areas without grass.

The paste marks serve two purposes: to mark a clan’s territory and to communicate with other clan members that an area has recently been foraged in. Brown hyenas also use latrines (communal toilets) which are distinctive collections of white faeces, often placed on crossroads, by gates or large trees. Latrines also serve to mark a clan’s territory.

Major threats

Without doubt, the most significant threat faced by brown hyenas residing outside of protected areas is human-wildlife conflict – persecution from humans. Although there is little evidence to show that brown hyenas can kill large livestock, farmers often consider them as pests. Their status as a livestock predator most likely stems from when they are seen scavenging from livestock carcasses. As a result, they are frequently trapped, shot, poisoned and even hunted with dogs as part of routine predator eradication activities.

Roads and traffic collisions also represent a cause of death for brown hyenas, however, the impact of this on the population is currently unknown. Brown hyena body parts are used in traditional medicines and are collected opportunistically from road kills. Although trophy hunting is allowed with a permit, brown hyenas are not currently a popular target for such activities.

A recent study found brown hyenas to have a natural low genetic diversity – even lower than cheetahs. Across southern Africa, fragmented populations of brown hyena exist in enclosed reserves, and without proper meta-population management, these isolated populations face the risk of inbreeding and at an extreme level, local extinction.

Final word

Although often undervalued and maligned, brown hyenas play an essential role as the ‘cleaners’ of the ecosystem; removing carcasses and carrion which might become sources for the spread of disease. Their populations continue to decline as a result of intense persecution, and this shy and elusive species will only continue to persist where their presence is tolerated, and their ecology understood. ![]()

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Sarah Edwards

Originally from the UK, Sarah completed her PhD on the human-wildlife conflict on commercial farmlands bordering two national parks in southern Namibia with the Brown Hyena Research Project in Luderitz, southern Namibia. Following this she completed a post-doc with the University of Pretoria in collaboration with the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research’s Cheetah Research Project in east Namibia, looking at various aspects of large carnivore ecology. Since January 2018 Sarah has been based at AfriCat on the Okonjima Nature Reserve where she is the lead researcher on AfriCat’s brown hyena research project, as well as supervising various other projects. Follow Sarah and her updates on brown hyena research on Twitter at @brownhyenas.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()