Restoring the

Great Karoo

one reintroduction

at a time

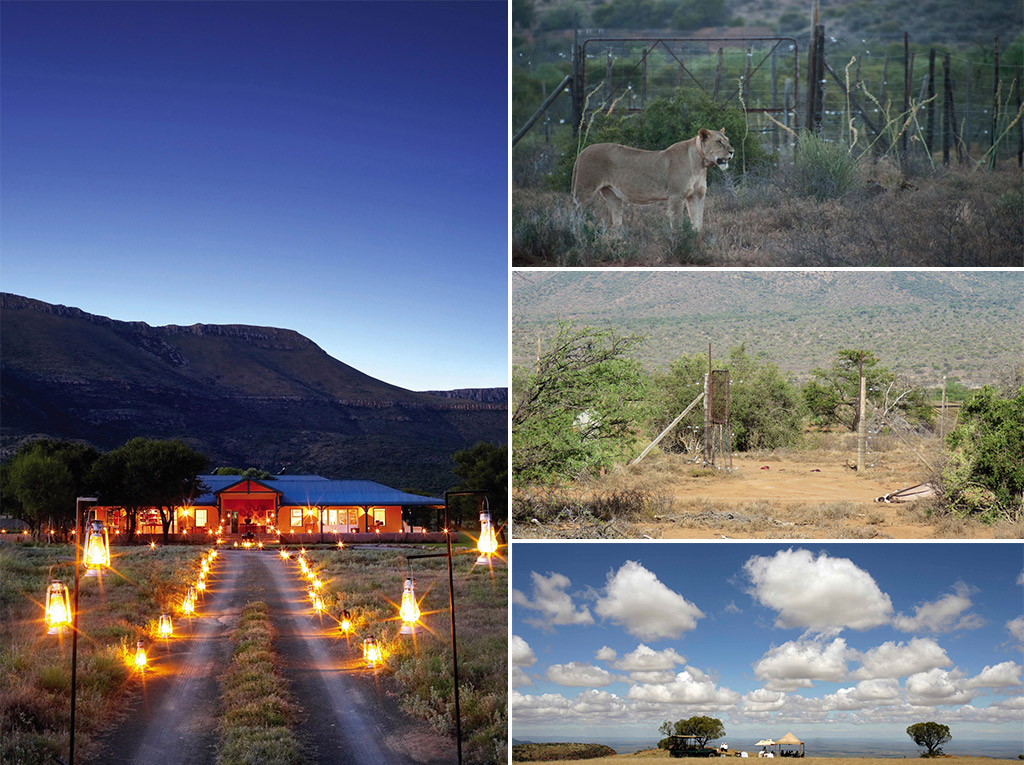

It was late in the evening when we sat down for a beautifully prepared three-course dinner at the impeccably decorated Manor House in Samara – a game reserve located near Graaff-Reinet in the Great Karoo. The main topic making the rounds was about the much-anticipated lion release, which took place earlier in the day. Well, technically it happened, though not in the way it was planned…

Waking up at the crack of dawn, the Samara team and a small group of lucky people, including yours truly, had eagerly made our way to the boma where two lions – Titus, a three-year-old male, and Sikelele, a four-year-old female – had been living for the past six weeks. Today was the day of their release into the reserve. A day that would herald the start of new beginnings in Samara history.

The lions had been spotted at the far end of the boma, sleeping under a bush. The gate was quickly opened, and a fresh gemsbok carcass lay just a few metres outside the entrance in the hopes to entice them out… We waited quietly in the game drive vehicles, about 25 metres away from the gate, the first warm rays of the sun hitting our backs as the sound of cameras zooming in on anything that moved broke the otherwise silent group.

A few minutes passed, then murmurings amongst the rangers and a few concerned glances were shared. Maybe they haven’t noticed the gate was open? Perhaps they need more time?

Half an hour later and still no sign. One of the rangers decided to check up on the location of the lions by circling the outside perimeter of the boma. He soon came back and dejectedly reported that the lions were still dozing under the bushes… flat-cats.

So, with the promise from Marnus, the general manager, that we would be informed as soon as any movement happened, we continued with our day, taking advantage of the available time to explore the vast landscape of Samara.

Now a lion release might not seem like a big deal – relocations happen all the time across the country – but in this case, it is quite significant for what Samara stands for, and what the owners and staff are hoping to achieve for the Great Karoo and its wildlife.

THE GREAT KAROO – THE ‘PLACE OF GREAT DRYNESS’

To understand more about the Great Karoo and the importance behind animal reintroductions by Samara, let’s first take a brief moment to step back in time to see how the Great Karoo became what it is today and why it’s such a unique and special place.

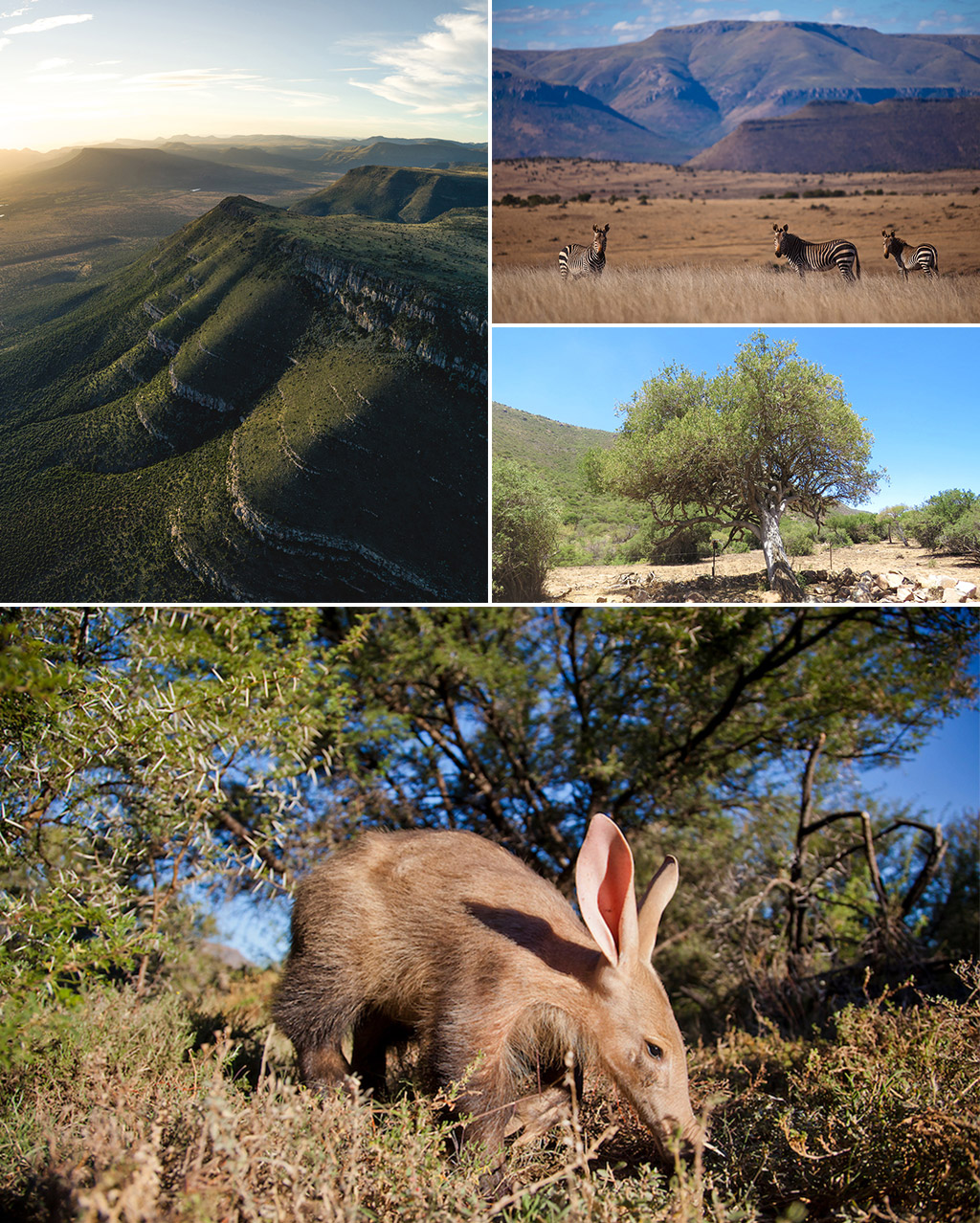

A semi-desert landscape, the Great Karoo is considered internationally famous in palaeontological circles for its abundance of pre-dinosaur fossils. The region covers two significant extinction events, the end-Permian (252 million years ago) and the end-Triassic (200 million years ago), and is home to rich fossil beds that preserve approximately 80 million years of vertebrate evolution that documents early primitive reptiles to the transitional stage between reptiles and mammals. This is the only place in the world where such an extended fossil record of the early evolution of ‘reptilian’ life is preserved in a single basin.

Incredible geological transformations over millions of years from glaciers to desert dunes to volcanic lava, and erosion over time, helped create the landscape that we see today.

Fast-forward to recent history, and we discover that less than two hundred years ago, large herds of antelope—such as eland, blesbok, and springbok—roamed the grass plains. Also present were quagga (now extinct), Cape buffalo, black rhino, ostrich, wildebeest, lions, leopards, painted wolves (African wild dogs), hyenas, and jackals. During what could have emulated the Great Wildebeest Migration in East Africa, the Karoo once played host to its very own migration spectacle of trekbokke – ‘migrating antelope’.

Not much is known about this phenomenon as it was never scientifically studied, but accounts from the 19th century tell of herds numbering in the millions.

In his book, The Migratory Springboks of South Africa, the Trekbokke (1925), S.C. Cronwright-Schreiner recalls the time in 1896 when he and two farmers, who were used to estimating small stock numbers, attempted to estimate the amount of migrating springboks, saying:

“With the aid of the field-glasses, we deliberately formed a careful estimate, taking them in sections and checking one another’s calculations. We eventually computed the number to be not less than five hundred thousand — half a million springboks in sight at one moment. I have no hesitation in saying that that estimate is not excessive.”

However, the springboks that they could see were just part of a massive herd, which in total covered an area of approximately 138 x 15 miles (222 x 24 km)!

Cronwright-Schreiner declared: “To say they migrate in millions is to employ an ordinary figure of speech, used vaguely to convey the idea of great numbers; but in the case of these bucks it is the literal truth.”

Following the rains and resultant nutrition across the Karoo basin, these migrating herds were of such enormity that it would sometimes take a week for all the springbok to pass.

They would eat their way across the landscape, an unstoppable force grazing their way through vegetation like a locust swarm. This may sound destructive but, like a natural veld fire, the springbok manure and hoof action helped prepare the soil for the next rainy season, and also helped to prune and invigorate the vegetation.

Lawrence G. Green’s book, Karoo (1955), provides a personal account by Gert van der Merwe of the great springbok migration:

“At last came a faint drumming. No doubt the Bushman had sensed this drumming hours before, with his ear to the ground. Only now could Gert hear it. The cloud of dust was dense and enormous, and the front rank of the springbok, running faster than galloping horses, could be seen. They were in such numbers that Gert found the sight frightening. He could see a front line of buck at least three miles long, but he could not estimate the depth. Ahead of the main body were swift voorlopers, moving along as though they were leading the army.”

Unfortunately, the last natural springbok migration was recorded in 1896. Due to human interference – by overzealous hunters and farmers dividing the land with barbed wire fences – the springboks faced too many obstacles to continue their natural route, and so it came to an end. And so the Great Karoo can no longer be compared to a Kenya safari highlights itinerary. Rather, it represents hope for the rewilding of the vast open plains that are still relatively undisturbed.

The expansion of human settlement in the Karoo caused much of the wildlife to be displaced or wiped out. With the occupation of the area by stock farmers, cattle, sheep and goats gradually replaced the wildlife and the grass receded along with the changed grazing and weather patterns.

It is at this point where Samara comes in. Reintroducing indigenous wildlife back into the Great Karoo has been a vision of Samara’s and its owners. Since the inception in 1997 of Samara, Mark and Sarah Tompkins have made it their mission to rewild the Great Karoo, recreating a self-sustaining ecosystem and restoring it to its former glory.

Over the last 22 years they have been painstakingly restoring eleven reclaimed farms that were once degraded and overgrazed, removing the internal fences of their 70,000 acres property and allowing the land to first rest and recuperate for at least a decade before reintroducing indigenous species that had gone locally extinct. They hope that one day the reserve could act as a link between other conservation areas – from Camdeboo National Park in the west to Mountain Zebra National Park in the east – creating an ecological corridor for wildlife to traverse, and perhaps even see the return of such great spectacles like the great springbok migration.

REINTRODUCTION SUCCESS STORIES

Since their journey began, Samara has engaged in an ambitious programme of animal reintroduction, some of the more notable reintroductions to date include:

Cheetah

In 2004, Sibella – a young female cheetah rescued from abuse at the hands of hunters – was the first among three cheetahs to be released into Samara. They were the first cheetahs to step back into the wilds of the Karoo in 130 years, after hunting and persecution drove them to local extinction in the 1870s. Sibella thrived in her new environment, successfully rearing 19 cubs in four litters before she died of natural causes in 2015 at the ripe old age of 14. Near the end of 2018 Samara was proud to announce that Sibella’s last daughter, Chilli, gave birth to a second litter of cubs.

White and desert-adapted black rhino

Already under serious threat from poaching and illegal trade, Samara did their part for rhino conservation in 2006 when they introduced white rhinos into the reserve. Then in 2013, they introduced south-western black rhino (Diceros bicornis bicornis) – a desert-adapted subspecies of the critically endangered black rhino. According to Samara, they are one of only two private reserves in South Africa to house this subspecies, the population stronghold being in South African National Parks and Namibia.

Samara takes rhino protection very seriously, and several measures form part of the anti-poaching strategy, including dehorning, patrols, surveillance and community education.

Springbok

In the hopes to restore what once was, Samara recently reintroduced 800 springbok to the reserve and has plans to increase that number to several thousand in a bid to recreate the natural ecosystem processes of holistic grazing. It is hoped that the reintroduction of springbok and the growth of the herds will enable the reserve to meet its objective of reversing decades of prior livestock overgrazing.

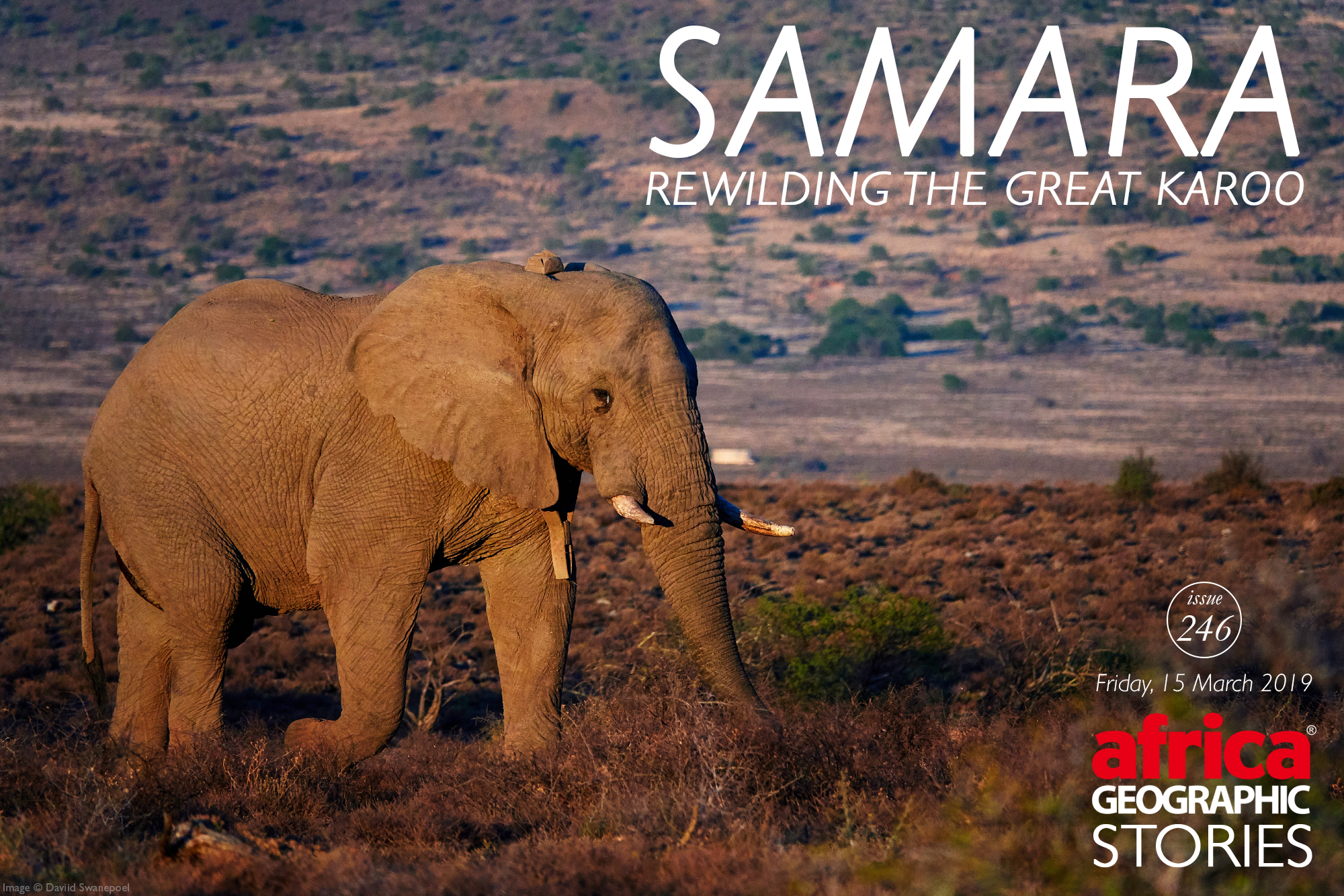

Elephants

After a 150-year absence, elephants were successfully reintroduced into Samara in October 2017. A founder family herd of six elephants came from Kwandwe Game Reserve near Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape and were soon joined by two mature bulls, who came from Phinda Private Game Reserve in KwaZulu-Natal, in 2018. Both elephant reintroductions were part-sponsored by the NGO Elephants, Rhinos, People.

The reintroduction of elephants has helped restore the function of the megaherbivore ecosystem processes in Samara. They have plenty to eat, and no supplementary feeding is required as they enjoy grazing mainly on cabbage trees and jacket plums that grow in the reserve.

Tracking collars have been fitted to two of the elephants: the sub-matriarch of the family herd, and the one bull, so that they can be tracked for conservation, ecotourism and academic purposes.

Lion

Reintroducing a founding lion pride has been Samara’s latest milestone in its journey to restoring a fully-functioning Great Karoo ecosystem. Lions once roamed the mountains and plains of the Karoo, though over time were wiped out by hunters and farmers, with the last wild lion spotted in the region in 1840. There is a pressing need for conservation initiatives targeting lions as the species has dwindled by 43% in the past 20 years, with current lion populations estimated to be between 20 000 and 30 000. However, researchers believe that the number is closer to 20,000.

At the end of 2018, a new chapter started as the first pride of two lions arrived at Samara, and were officially released into the reserve in January 2019. This marks Samara as the first Big 5 private game reserve in the Great Karoo region, and at the same time, this forever shifts the predator-prey dynamic in the reserve.

Additional reintroductions over the years have included dozens of plains game like red hartebeest, eland and Cape mountain zebra, to name but a few. Incredibly there has also been the natural return of other species, such as the elusive Cape leopard and Cape vultures.

A WELCOME DINNER INTERRUPTION

Now that we’ve covered a bit of the background, it’s back to the evening’s dinner after a long day out with no word from the rangers as to the movements (or lack thereof) of the lions…

We were finishing off our main course when Veronica, the assistant manager, approached the table.

“I have an announcement to make,” she declared with a hint of a smile.

The table quietened down, turning towards her with anticipation

“I have a message from Marnus,” she went on calmly. “He says that the lions have finally left the boma and that you must all head outside as he is waiting to take you to where they are.”

It took us a mere moment to process what she had just said… and then all hell broke loose. Napkins flew into the air, chairs were pushed hastily away, and the room erupted in an energetic frenzy as everyone scrambled to get their cameras and jackets while hot-stepping it to where Marnus was waiting in the vehicle.

Dessert would have to wait!

Soon we were on the road for the short ride to the boma. It was pitch black and slightly chilly, and Marnus drove by the boma’s gate, left open since the morning, surveying the area with a spotlight for any sign of the lions – the gemsbok carcass lay untouched.

Had they really left without feeding? Surely they were hungry? Would they vanish into the night, leaving us equally excited yet disappointed at the same time? Questions and theories to their location flew around in hushed whispers.

Trying to remain positive, we slowly drove around the area, the spotlight dancing across the landscape, creating shadows that had us second-guessing, when suddenly it fell upon a sleek feline figure walking about a hundred or so metres away – everyone gasped – it was Titus! Moving like the ghost of his ancestors, he was silently making his way through the thick acacia trees towards the carcass.

In anticipation, we drove back to the carcass, only to find that Sikelele had returned in the last few minutes and was already tucking into her dinner, unperturbed by our presence.

Our patience was rewarded when Titus soon joined her — seeing the two lions calmly eating together sparked a flurry of muted congratulations and rejoicing amongst those of us lucky enough to witness this historic event. That night, after speeches and champagne, a sense of relief and hope for the future took us to bed for a blissful night’s sleep, while the founding lion pride of Samara strolled under the stars, exploring their new home in the Great Karoo.

ABOUT THE KAROO

The Karoo covers almost 40% of South Africa’s land surface and stretches over the provinces of the Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, Free State, and Western Cape. No exact definition of what constitutes the Karoo is available, so its extent is also not precisely defined.

The Karoo, however, is distinctively divided into the Great Karoo (or Groot Karoo) and the Little Karoo (or Klein Karoo) by the Swartberg Mountain Range area. Both regions lie almost entirely within two of South Africa’s eight botanical biomes: the Nama Karoo and the Succulent Karoo.

The massive Nama Karoo is South Africa’s second-largest biome which extends into southeastern Namibia. It is defined as a vast semi-desert region, and the name is derived from the Khoi San word kuru, meaning ‘dry’. The Succulent Karoo covers the arid western parts of South Africa, including Namaqualand and the Richtersveld, up to the south-west region of Namibia. It is distinguished by its arid or semi-arid climate, allowing for a rich diversity of succulent plants and animals.

The Karoo is partly defined by its topography, geology and climate, and above all, its low rainfall, arid air, cloudless skies, and extremes of heat and cold. It is also home to the widest variety of succulents on Earth. Here you can find the richest desert floras in the world, with 40% of these species not found anywhere else on the planet.

ABOUT SAMARA

Samara Karoo Reserve is a family-run, award-winning, malaria-free, Big 5 reserve in the Great Karoo. It is located in the Eastern Cape province, 53 km southeast of Graaff-Reinet – the country’s fourth oldest town. Spanning 70,000 acres of Great Karoo wilderness, Samara offers a Big 5 safari with a difference.

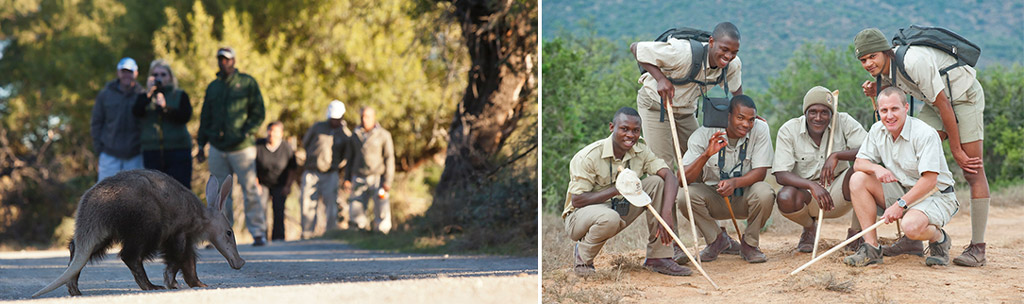

Consisting of 11 former livestock farms assembled since 1997, Samara’s vision is nothing less than the rehabilitation of an entire landscape. Key to the Samara experience is the concept of co-creation, where every guest plays a role in rewilding the landscape and preserving it for posterity. Activities include game drives, guided walks, wilderness picnics, cheetah tracking on foot, aardvark spotting (best sightings to be had in winter), birding, hiking and a luxury star bed (open October to April). Children of all ages are welcome, and there is a Samara Kids Programme that caters to children up to the age of 12 years old.

Thea was graciously hosted at one of the two accommodation options at Samara:

The Karoo Lodge is a restored farmhouse encircled by a natural amphitheatre of mountains. Combining colonial comforts and modern-day luxuries with a rustic and welcoming feel, the Karoo Lodge is the perfect place to relax, either outside by the pool or on the verandah. The lodge has nine, en-suite double rooms of varying sizes and caters for individual travellers, couples and families.

The luxurious Manor House is a modern yet understated villa which reflects the local Karoo landscape and traditions with a unique twist. It comprises four, en-suite luxury suites, which can be booked independently or the entire villa can be taken over on an exclusive-use basis. This option is popular with families and groups looking for privacy, indulgence and complete relaxation.

For those seeking just a bit more privacy and adventure, Samara offers a star bed – a bedroom on a raised wooden platform. The star bed is some distance from the camp and overlooks the Milk River, where wildlife comes to drink. You will be dropped off at the private star bed in the evening and picked up the following morning. Your stay in the star bed includes a romantic sundowner drink followed by a moon-lit dinner. You will sleep high up and safe from predators and things that go bump in the night.

Your bed is as comfortable as those back in the camp, and a mosquito net protects you from pesky insects. The treehouse has a toilet and a hand basin. Awaken the next morning to the big skies and birdsong of the Karoo as another beautiful day dawns in Africa, before being collected and taken back to the main camp to freshen up. This is a wonderful, romantic and very memorable twist to any safari.

The Tracker Academy

The Tracker Academy, a training division of the SA College for Tourism, operating under the auspices of the Peace Parks Foundation and funded by the Rupert Family Trust, was founded and is hosted at Samara. The one-year full-time intensive course into the dying science of tracking, led by experienced trainers, is the first of its kind in Southern Africa.

Samara makes its land available free of charge to the Tracker Academy for all its semi-arid practical training sessions and as part of its charitable donation to the Academy, also provides lecturing facilities and accommodation for the trainees.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

As a former field guide and teacher, Thea has combined her passion for the English language and love of wildlife to work behind the scenes as a content editor sharing African wildlife, travel and culture with a global online audience. When not in front of the screen she makes time to get out and explore the beautiful Cape Town wilderness in search for her favourite reptile species (and other fascinating creatures, of course).

As a former field guide and teacher, Thea has combined her passion for the English language and love of wildlife to work behind the scenes as a content editor sharing African wildlife, travel and culture with a global online audience. When not in front of the screen she makes time to get out and explore the beautiful Cape Town wilderness in search for her favourite reptile species (and other fascinating creatures, of course).

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()