Africa’s golden valley

It is easy to understand why the symbolism attached to valleys is similar across cultures and continents. They are places that represent life and beauty – inspiring artists, poets and musicians. For the more practically-minded, valleys are sheltered places of safety, guarded by mountains and made fertile by rivers and streams flowing from their slopes. Luangwa Valley is the perfect African example – a vast Zambian wilderness; a playground for tourists seeking an authentic, unfussy safari experience.

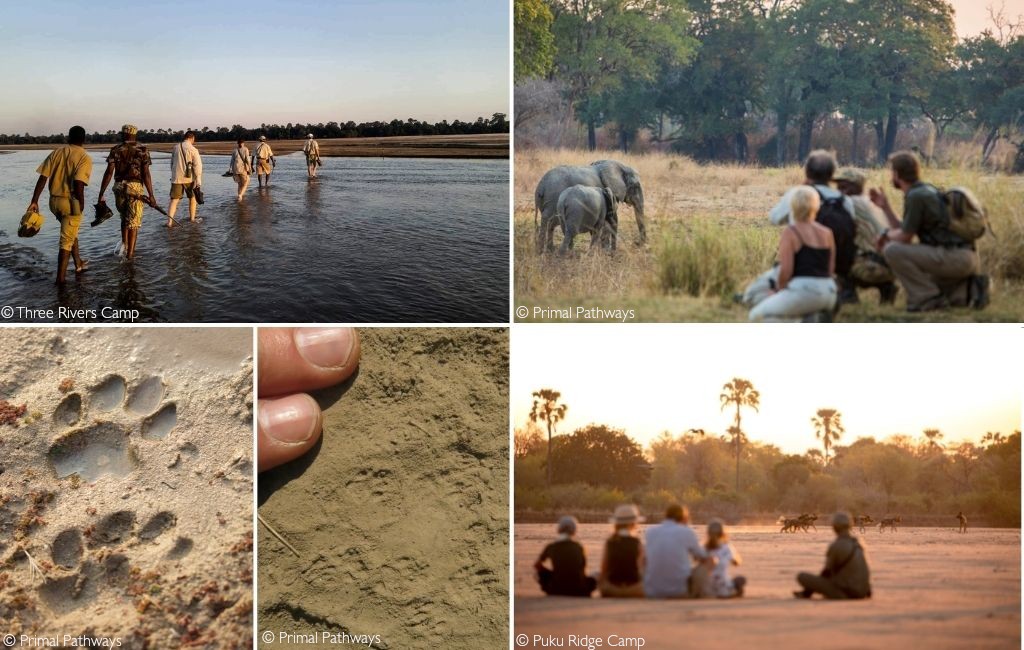

It is rugged unspoilt, and best explored on foot in the company of some of Africa’s best guides.

A river runs through it

Life in the Luangwa Valley centres around the Luangwa River and its rich floodplains that spill over into the surrounding plains, savannas and woodlands. The eponymous river is one of Zambia’s most extensive, rising in the north-eastern corner of the country and meandering south-west before flowing into the Zambezi River. As part of the tail-end of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, the ancient tectonic forces that shaped the landscape laid the foundations for spectacular scenery. The magnificent Muchinga Mountains form an escarpment that plunges some 700m to the valley floor, which reaches a width of up to 100km wide. The river changes its course regularly when in flood, creating new oxbow lakes and hairpin bends for the hippos to occupy in their hundreds.

There are four national parks within the Luangwa Valley: South Luangwa National Park (SLNP), North Luangwa National Park (NLNP), Luambe National Park (Luambe NP) and Lukusuzi National Park (Lukusuzi NP). These are surrounded by numerous unfenced Game Management Areas and, with the Mid-Zambezi Valley, the ecosystem covers a relatively undisturbed 70,000km2 of wilderness.

The rich and vibrant habitats are home to some of the highest densities of wildlife in Zambia. According to the Zambian Carnivore Programme, this section of eastern Zambia boasts the largest lion population in the country and the second largest population of African painted wolves. The region is also home to a Luangwa endemic: the Thornicroft’s giraffe (suspected subspecies of the Masai giraffe). Other Zambian specialities include the Cookson’s wildebeest (a subspecies of the blue wildebeest) and the Crawshay’s zebra (a subspecies of the plains zebra).

On foot in the valley

Luangwa is often referred to as the home of the walking safari, and the region was among the first places on the continent to offer walking safaris. Game warden, conservationist, and travel-pioneer Norman Carr famously believed that it was impossible to know an area without exploring it properly on foot. Generations of expert guides have followed in his footsteps, trained to embrace the same ethos and appreciation for the wild as the first walking guides.

There is a twinge of adrenaline heading out on foot into the presence of Africa’s most revered (and potentially dangerous) animals. The genuine value, however, lies in the complete nature immersion. For most, the ordinary human senses are dulled by overstimulation and frenetic schedules. So, it is almost astonishing how, when in the company of an expert guide, it is suddenly possible to revert to a far more primal state of awareness. The sudden amplification of sound, smell and touch (and fear) can be profoundly grounding.

What is more, the Luangwa Valley is a biodiversity hotspot. Rather than hoping for an encounter with a big animal (which will likely happen regardless), revel in the small things. Appreciate the morning light catching the dew of a perfect spider web or marvel at the tenacity of a dung beetle in action. Stop to admire the intricate network of veins in an elephant track and the careful construction of a batis nest or run a hand over the rough bark of an ancient ebony tree. The magic of the Luangwa Valley is so overwhelming that it takes time to soak in fully.

South Luangwa National Park

The largest of the valley’s four national parks, South Luangwa National Park (SLNP), is also the most popular (though it remains almost entirely unspoilt and operates at relatively low tourist densities). The Muchinga Escarpment borders the 9,059km2 park along its western and northern edges, while much of the infrastructure centres around the Luangwa River and its many tributaries. As a general rule, the Mfuwe area is the park’s busiest, and sightings can become somewhat frenetic during the high season. The Nsefu sector of the park is quieter and more remote, offering a more exclusive feel.

Along with enormous herds of elephants and buffalo, SLNP is renowned for its dazzling leopard sightings, and visitors are regularly treated to more than one leopard in a day. SLNP is also home to one of the most well-known elephant herds in the world. These brazen pachyderms famously return year after year to snack on the wild mangos in Mfuwe Lodge. The herds merrily stride through the reception area, oblivious to the amazement of guests and staff (or perhaps simply accepting it as their due).

Just before the start of the rainy season in November, the park’s skies are filled with flashes of pink as the carmine bee-eaters return for the summer. These gloriously coloured birds nest in holes excavated in sandbanks, and appreciative guests can while away the hours at a hide watching the flashing colours as the birds prepare for the breeding season. (Have a look at this wonderful trip report for an account of a South Luangwa safari)

North Luangwa NP

North Luangwa National Park is far more remote, and visitors here are unlikely to encounter another tourist group in the entire 4,636 km2. The road network is relatively sparse, and the camps are rustic and fully immersive, designed to be dismantled during the rainy season.

This park is not suitable for solo exploration, and permission to enter must be secured from the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Services ahead of time. Though elephant and leopard sightings are not as common as in SLNP, there are large prides of lions accustomed to people on foot.

Forty years ago, Zambia had one of the largest black rhino populations in Africa, with around a third of them found in the Luangwa Valley. In 1998, they were declared extinct in Zambia due to rampant poaching. With increasing efforts to secure SLNP and NLNP in particular, the North Luangwa Conservation Programme has released 25 black rhinos into the park since 2003, effectively re-establishing a viable population.

The woodlands of the escarpment offer the best chance of spotting both sable and roan antelope, as well as unique birding opportunities. Over 400 different species of birds have been recorded in both SLNP and NLNP.

Luambe National Park

Situated between NLNP and SLNP, Luambe NP lies on the eastern side of the Luangwa River and, at less than 300km2, is one of Zambia’s smallest national parks. After decades of neglect and a shortage of resources, a 2014 report found that the park held just 5% of its wildlife potential. Fortunately, things have turned around in recent years. The Luambe Conservation Project was created to restore the park to its former glory as one of the most biodiverse parks in Zambia.

As a result, the wildlife is gradually recovering, and visitors have the entire park to themselves. There is only one camp currently offering accommodation in Luambe, consisting of five comfortable safari tents. Not only are tourists treated to Zambian-style rustic luxury, but they can also witness the restoration in action. From monitoring camera traps and tracking African painted wolves to tagging vultures and recording nesting patterns of the carmine bee-eaters, guests are welcomed as an essential part of the conservation recovery process.

Lukusuzi National Park

Lukusuzi NP is the fourth and final national park considered to be part of the Luangwa Valley. Situated to the southeast of Luambe, the 2,720km2 park is devoid of infrastructure, facilities, or accommodation. A single dirt track traverses the park, but even this is only traversable in a 4X4 vehicle during the dry season. Little is known about the state of the park’s wildlife populations.

The when, why and how

Luangwa Valley is best experienced during the dry season, especially for novice safari-goers. From around May until October, all camps are fully operational, and wildlife sightings are best as animals congregate around the remaining water. From November onwards, the rains arrive and turn the valley’s black cotton soils into a sticky sludge that not even the most experienced drivers will be able to navigate. Only a handful of South Luangwa’s lodges remain open during the wet season. Most bush camps are packed away, only to be resurrected in a flurry of activity at the start of the following dry season. Those lodges that do remain open during the green season, when birding is spectacular, take advantage of the water by offering river trips and boat cruises.

Accommodation options range from budget camps (only in or bordering SLNP) to more luxurious and exclusive lodges and private villas. However, true to form for Luangwa Valley, even the most expensive lodges share the authentic, down-to-earth tone that epitomises the Zambian safari experience. It is an approach that recognises that the real grandeur lies in the scenery, the wildlife, and the stories. Why waste time fussing with canapes when you can watch the sunset with your feet soaking in the cool waters of the river, swapping tales of the day’s sightings?

Want to plan your Luangwa Valley safari? Scroll down to the end of this story to research and get in touch with our travel team to start the discussion.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()