Tracking sea turtles in iSimangaliso

As our guide brought the open game vehicle coasting to a halt, the only sound was of waves breaking gently on the sand. That morning, Sodwana Bay had been clamorous with tractors and trailers, speedboats and scuba divers. But now, late at night, the beach was utterly empty. And out there, somewhere, an ancient and awe-inspiring story was unfolding.

You see, as well as being one of the world’s top dive sites, Sodwana Bay in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park is also one of the very few places in southern Africa where sea turtles nest. Of the five species of turtles found in these seas, the two largest come here to lay their eggs. ISimangaliso is Africa’s last primary nesting site for leatherbacks and loggerheads.

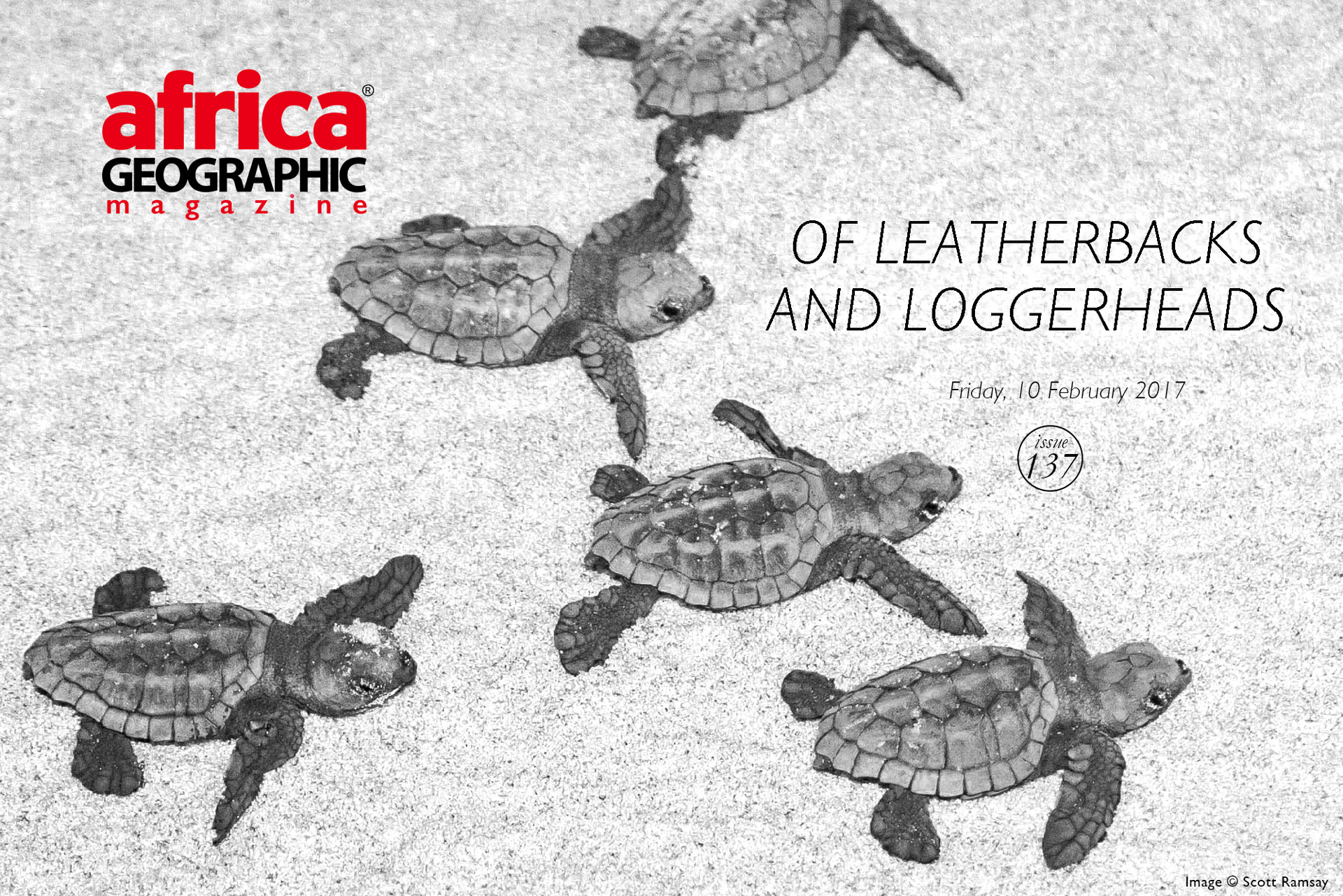

Each year, from November to January, the giant tracks of female leatherback and loggerhead turtles emerge from the surf, looking like paths left by aquatic tanks. A couple of months later, the tiny, almost invisible trails of baby turtles scatter from holes below the dunes. Not all of them reach the sea.

The serious circumstances of sea turtles

It was mid-January, so we were just in time to witness both sides of this 100-million-year-old ritual. Our guide was Peter Jacobs of Ufudu Turtle Tours. He’s an honorary wildlife officer with Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife who’s passionate about protecting Sodwana Bay’s sea turtles. The tours he runs on this 10-mile stretch of beach aren’t just for entertainment. They’re a way to create a public appreciation for these magnificent creatures – and some awareness of their plight.

After Peter gave us an introductory talk about sea turtles, we drove north along the beach, below the high tide mark. The only illumination came from our dim yellow headlights, the pale glow of a gibbous moon slipping between clouds, and the rhythmic slash of the lighthouse on the hill. Unfortunately, said Peter, this was too much light. Ideally, the lighthouse would be turned off, and so would our headlights. Nothing besides the moon and stars should shine on a beach where turtles are nesting.

That’s because turtles are incredibly sensitive to light. Female turtles navigate towards the shore using the dark outline of vegetated dunes against the night sky. Hatchlings find their way to the sea by orienting themselves to its reflective glimmer. Any artificial light at a sea turtle nesting site dramatically lowers their chances of success.

And it’s not as if their odds are particularly good in the first place. Although leatherback and loggerhead turtles usually lay around 100 eggs in a nest, and dig on average five nests in a season, it’s estimated that scarcely one in a thousand hatchlings make it to maturity.

From the moment a sea turtle egg hits the damp sand of a nest, it’s under threat. Once the female turtle has dragged herself laboriously back to the ocean, the eggs are left entirely unprotected. Dogs and jackals, ants and ghost crabs, snakes, gulls, rats, cats and mongooses all adore a tasty turtle egg.

Then, once the turtle hatches, it has to push its way up through the sand and hope for a clear passage to the sea. This, however, is highly unlikely. While adult leatherbacks and loggerheads weigh hundreds of pounds and are virtually immune to natural predators, their hatchlings are just a couple of inches long and weigh less than two ounces.

Thousands of stalk-eyed ghost crabs patrol the dunes, waiting to drag the tiny turtles away. If a hatchling doesn’t reach water before daylight, it will die of dehydration or be scooped up by gulls and raptors. Even if a baby turtle successfully reaches the ocean, there’s no respite. Squid, fish, sharks and eels are all waiting to gobble it up.

Finding Fynn

Peter stopped the vehicle a short stretch along the beach. He explained that he and a group of volunteers monitor each nest they locate. A loggerhead nest nearby was due to hatch any day now. Perhaps we would be lucky enough to see it happen. We waited while he trotted up the dune with a red torch (red light doesn’t confuse turtles) and jumped out to join him when he beckoned.

“We just missed it,” said Peter, kneeling beside a hollow in the sand, around which some rubbery egg fragments lay. “They probably came out about half an hour ago. Let’s see if there are any stragglers left in the nest.” He dug carefully. “Aaah, this one hatched but didn’t make it. It might have suffocated.”

There were no live turtles in the nest, but Peter noticed several trails leading away from it towards the dunes. He suggested we fetch our torches to see if we could find any hatchlings that had been kidnapped by ghost crabs.

Holding my headlamp close to the ground to minimise its range, I followed a pair of tracks into the hollow of a dune. “Oh! I’ve found one!” The little loggerhead had turned towards my torchlight and was determinedly forging its way onwards with three flippers.

“A crab must have dragged it by its front flipper and damaged it,” said Peter when he saw it. “It’s highly unlikely that this one would have survived anyway. It’s lost in the dunes, out of sight of the sea, and it’s injured. So I’m going to allow you to help it.”

This sounded like an odd thing for Peter to say, but he told us that people’s attempts to help turtle hatchlings could often do more harm than good. Picking them up transmits bacteria they’re not equipped to fight. And carrying them to the sea instead of letting them walk means their flippers don’t get the vital exercise they need to strengthen them for swimming.

So we scooped the little loggerhead up in a handful of sand and carried it back to the nest. Then, since we were desperate to be helpful, Peter allowed us to use torches to guide it to the water.

By now, I had named the turtle Fynn. (There’s no way to tell a turtle’s sex by sight, so I’d decided he was a boy.) I growled whenever someone shone a torch, or turned on a cellphone or camera that wasn’t directly in line with his path to the sea, because, each time, no matter how faint it was, Fynn would turn towards the light, and away from the water.

So I crawled in front of him with my torch, smoothing the sand, and saying stupid things like “Come on, Fynn! You’re a champ! You can do it!” Never has 100 metres felt so far. But at last, Fynn’s first wave washed over him. His flippers waggled with what looked like delight. We clapped and cheered. Then another wave whisked him out and away.

Beyond the beach, endless dangers waited: marlin, barracuda, tiger sharks – predators too numerous to name. And then there are the human perils of plastic, pollution, poaching, fishing lines, nets and boats. Fynn has less than a one in a thousand chance of reaching adulthood. But, at least he lived long enough to swim.

Lady Leatherback

Exhilarated by this remarkable encounter, I felt that the evening couldn’t possibly get any better. Although, as we enjoyed a midnight feast on the beach, I admitted that it would be nice to see a leatherback turtle too.

Leatherback turtles are the rockstars of the turtle world. They grow the longest (up to 7 feet), weigh the most (up to almost a ton), swim the fastest (up to 22 miles an hour), dive the deepest (up to 1,200 metres) and range the furthest (from Norway to New Zealand). And they do this all on a strict diet of jellyfish, which are 95 per cent water.

So it was an immense thrill, when, on our way back along the beach, Peter spotted the massive shape of a female leatherback. She’d already reached the dunes and was looking for a place to lay her eggs. We waited quietly in the dark until she started digging. Only then did Peter permit us to approach, on condition that we kept well behind her and did not use torches, cellphones or cameras.

She was a giantess, dwarfing us all. And she was beautiful. Her soft, leathery carapace was deep blue-black splotched with white. It looked as though she had mapped the galaxies. Her dappled flippers and neck shaded down to shell-like pink. The salt glands above her large, dark eyes made it seem as though she was shedding soulful tears, and her breath hissed sharply with the effort of digging.

Patiently, methodically, meticulously, the leatherback’s rear flippers scooped and slapped the sand aside. Even though the tide was rising and our time was running out, we were mesmerised. At last, the nest was as deep as the turtle could make it and her eggs, looking precisely like ping pong balls, started to drop into it.

With luck, in a few weeks, most of those eggs would hatch. Dozens of miniature leatherback turtles would toddle towards the starlit sea. And then, perhaps, many years later, one of her offspring would emerge again on this beach – in almost the same spot – to repeat this mysterious cycle of life.

What to do in iSimangaliso

Ufudu Turtle Tours conduct turtle tours in Sodwana Bay from November to May. Tours are around low tide times in the evenings or late at night and last around four hours.

With coral reefs that boast two-thirds of the species diversity of the Great Barrier Reef in an area a tenth of the size, scuba diving in Sodwana Bay is not to be missed. Coral Divers is a PADI 5 star Gold Palm IDC Centre, offering every level of dive instruction.

Even if you’ve never scuba dived before, they’ll have you safely under the sea within a day. In just three dives, I was lucky enough to see ragged-toothed sharks, green turtles, eagle rays, moray eels and hundreds of species of fish and corals.

The Fig Forest guided walking trail in uMkhuze offers birders the chance to spot the incredibly rare Pel’s fishing owl. We weren’t in luck that day, but we did see squadrons of trumpeter hornbills, thousands of butterflies, and, of course, spectacular sycamore figs.

On a night game drive in the Eastern Shores section of iSimangaliso with SHAKAbarker Tours, we learned how to spot chameleons in the dark, and saw plenty of larger animals, including elephants, kudu, buffalo and hippopotamus.

We also took a leisurely boat cruise to view hippos and crocs in the St Lucia Estuary with Shoreline Boat and Walking Safaris.

About the author

Alison Westwood is a South African travel writer based in Cape Town. She’s written and photographed for magazines, travel websites and travel guides, and has recently co-authored a book about Secret Cape Town.

Alison Westwood is a South African travel writer based in Cape Town. She’s written and photographed for magazines, travel websites and travel guides, and has recently co-authored a book about Secret Cape Town.

Alison has interviewed some of Africa’s most interesting travellers as well as investigating all sorts of travel-related issues, from elephant culling to carbon-offsets. In addition to travelling, Alison loves to hike. She blogs about getting lost in the mountains on 52 Cape Town Hikes.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()