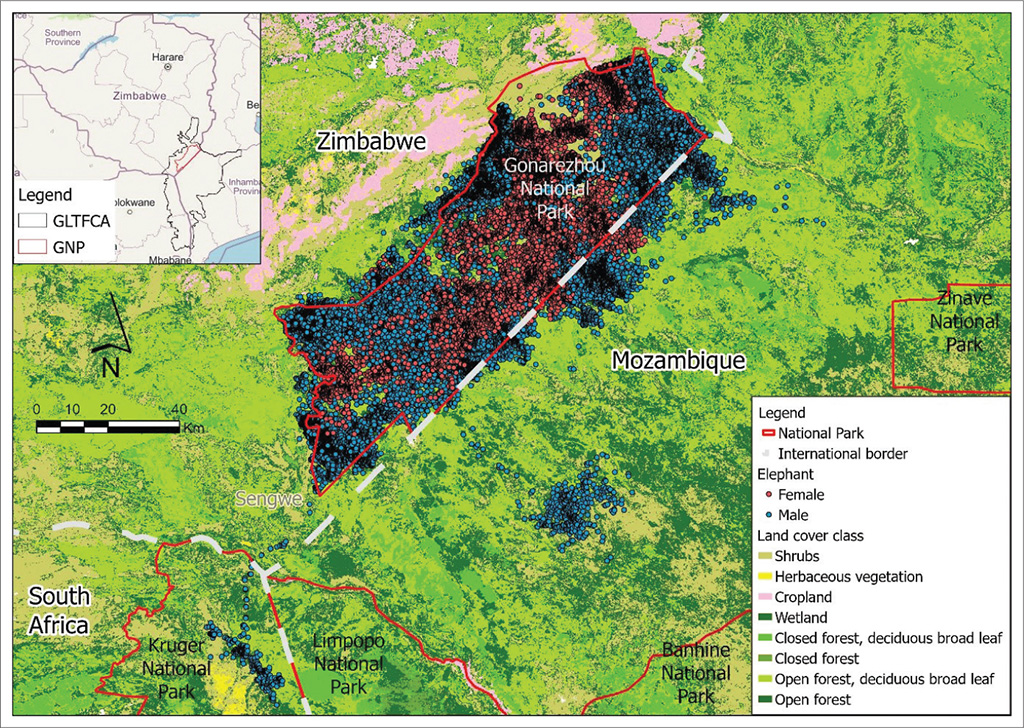

- A multi-year tracking study of 26 elephants reveals how individuals use landscapes around Gonarezhou NP, Zimbabwe, and where movement remains possible.

- Elephants rarely travel far outside the park, favouring the open boundary with Mozambique over the heavily settled Sengwe corridor.

- Males roam much further than females, while family groups stay close to the park and avoid human-dominated areas.

- Seasonal conditions strongly shape dispersal, with most movement occurring in the cool-dry season when resources are scarce.

- Human presence, fences and fragmented habitat limit connectivity, increasing ecological pressure inside the park and highlighting the need to restore corridors.

Want to see elephants on an African safari? Check out our safari ideas here, or let our travel experts plan the perfect African safari for you by clicking here.

Want to see elephants on an African safari? Check out our safari ideas here, or let our travel experts plan the perfect African safari for you by clicking here.

Understanding how elephants move through landscapes is essential for designing protected areas that actually work. A study from Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe examines where elephants go when they leave the park, how far they travel, and what shapes these decisions. The findings highlight both the resilience of elephants in human-influenced environments and the structural limits that still confine their range.

At stake is the long-term viability of one of southern Africa’s fastest-growing elephant populations – and ecological connectivity across the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area (GLTFCA).

Why movement matters for elephants

African savannah elephants are wide-ranging herbivores that rely on mobility to access water, food, shade and mates. Their seasonal dispersal also protects habitats from overuse. Most protected areas, however, are now islands in growing human landscapes.

Connectivity between parks is therefore essential. Ecological corridors – unfenced stretches of natural habitat linking protected areas – allow wildlife to move safely between core refuges. Without such linkages, isolated populations face increasing density pressures, habitat degradation and, eventually, genetic risks.

Gonarezhou’s elephant population is growing at roughly 6% per year, and the surrounding mosaic of communities, farms and fenced boundaries makes dispersal increasingly difficult. Against this backdrop, researchers collared 26 adult elephants between 2016 and 2022 to understand whether, when and how they leave the park.

Where elephants go when they leave Gonarezhou

The most striking finding is that elephants rarely disperse far from the park. Movement outside Gonarezhou increased only after 2020, mainly through the unfenced 100km eastern boundary with Mozambique. In contrast, Zimbabwe’s Sengwe communal lands to the south – part of the official wildlife corridor to Kruger National Park – saw far less elephant activity.

Overall, 68% of all out-of-park locations were in Mozambique, while 32% were in Sengwe. Elephants avoided densely settled areas, especially during the day, indicating strong sensitivity to human presence.

Distance differences: males roam, females remain close

Sex played a significant role in dispersal patterns: male elephants ranged far more extensively, sometimes travelling up to 60 km beyond the park boundary, while females, typically moving in family groups, remained within about 15km of Gonarezhou. These differences align with well-known behavioural tendencies, with bulls roaming widely in search of resources or mates, and family groups avoiding riskier areas, particularly where fences or human activity may limit their ability to move safely.

When elephants choose to leave

Seasonality strongly shaped movement. The study divided the year into three climatic periods:

- Cool-dry season (Apr–Jul)

- Hot-dry season (Aug–Nov)

- Hot-wet season (Dec–Mar)

Elephants dispersed most during the cool-dry season, when water and vegetation become patchier across southern Africa. This matches broader elephant ecology: dry-season shortages often push elephants beyond fenced boundaries in search of browse and water.

By contrast, dispersal declined sharply during the hot-wet season, when water and forage are widely available inside Gonarezhou. During this time, the park functions as a seasonal refuge.

How elephants use human-dominated landscapes

Human–elephant conflict often spikes where elephants leave protected areas, particularly when they raid crops or encounter homes, fields or livestock. Many species adjust their behaviour to avoid such risks, including shifting to nocturnal movement.

This risk-avoidance pattern was evident in Sengwe: elephants entered the communal lands mostly at night, minimising daytime contact with people. Yet, despite global patterns of crop-raiding, the study found that collared elephants spent little time in cropland, suggesting either limited availability or strong avoidance.

The Mozambique side, in contrast, offered lower human densities, private wildlife concessions, and artificial water points. These features likely encouraged greater elephant presence, especially during the dry season.

What habitats do elephants prefer outside the park

Land cover classification revealed subtle but essential patterns. Male elephants shifted toward forested areas (deciduous broadleaf) when outside Gonarezhou. Females continued to favour shrublands, similar to their habitat preferences inside the park.

Forested areas may offer concealment, shade or seasonal browse. Shrublands may feel safer for family groups – open enough to detect threats and accessible enough for calves.

Barriers, corridors and the limits of dispersal

Even with an open eastern boundary, Gonarezhou remains partially encircled by veterinary and management fences. These fixed barriers may restrict female movement more than male (female elephants, travelling in family groups with calves, are especially unlikely to cross obstacles or enter risky areas), and may also prevent elephants from reaching Zinave or Banhine National Parks in Mozambique.

The Sengwe–Tshipise corridor, intended to restore natural movement between Gonarezhou and Kruger, remains heavily settled, fragmented and risky for elephants. Some bulls in this study did successfully travel from Gonarezhou to Kruger and back – living proof that connectivity is still possible – but these individuals appear to be exceptions.

Conservation of elephants

This study’s central message is clear: Gonarezhou’s elephants are inclined to move beyond the park, but the surrounding landscape seldom allows it. For a rapidly growing population confined within a fenced and semi-isolated protected area, this limitation carries several consequences. Elephant numbers continue to rise inside the park, increasing pressure on vegetation. Opportunities for the population to expand into under-utilised protected areas in Mozambique are lost, while the small amount of movement that does occur – often at night in communal lands – heightens the risk of human–elephant conflict. At a broader scale, restricted movement undermines functional connectivity across the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area (GLTFCA), a system designed to support wildlife dispersal between countries.

Given these challenges, the authors emphasise that maintaining and restoring ecological connectivity is essential. They recommend addressing the barriers that prevent elephants from moving naturally toward Zinave and Banhine National Parks, and prioritising targeted conservation efforts and pilot projects within the Sengwe corridor. Additional priorities include exploring non-lethal strategies to reduce conflict between elephants and local communities, considering the potential role of artificial water points in non-protected areas, and improving understanding of the “fear landscape” that suppresses female movement in particular. Finally, the study underscores the importance of strong community engagement in areas where people live along potential wildlife corridors, as local support is fundamental to any long-term solution.

What the study adds

For managers and policymakers, this research provides rare, high-resolution evidence of how elephants actually navigate a transboundary landscape. Despite political ambitions for seamless wildlife movement across borders, the reality on the ground is more constrained.

Elephants, especially males, will move where opportunities exist. But without coordinated action to secure and rehabilitate corridors, Gonarezhou risks becoming an ecological island – and its elephants unable to play their full role in the wider GLTFCA system.

Reference

Mandinyenya, B.R., Mingione, M., Traill, L.W. & Attorre, F., 2025, ‘Elephants’ habitat use and behaviour when outside of Gonarezhou National Park’, Koedoe 67(1), a1842. https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v67i1.1842

Further reading

- Gonarezhou is a conservation success story and iconic wilderness destination for those seeking true wilderness. Read more about Gonarezhou here

- Explore wild beauty, 4×4 trails, rare wildlife & local culture in Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park – part of a visionary peace park

- How do elephants move across southern Africa through protected areas and beyond? New research explores the value of habitat connectivity

- Scientists map 40 potential wildlife corridors to link the Garden Route, Baviaanskloof & Addo: a vision of a Cape mega-living landscape

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()