The river horses of Africa

It was just before the arrival of the rains in the South African Lowveld, when the heat seems relentless. We had come across a solitary bull hippopotamus, squeezed into a tiny patch of remaining mud, the skin on his back cracked and dry. I parked the safari vehicle at a comfortable distance, observing his body language for any signs of upset, as hippos are understandably grumpy at the height of the dry season. But he could have been dead for all the movement he showed – only the slight twitches of his ears gave him away as he snoozed.

We sat for a while, contemplating the harshness of nature before I did something unfortunate. It was blazing hot, and there was not a single patch of shade. And so, I pulled out a spray-on sunscreen. Without thinking, I depressed the nozzle, and all hell broke loose…

With a sound akin to the unblocking of the world’s largest toilet, the bull extracted himself from the mud wallow and launched himself at us, mouth agape and enormous tusks front and centre. In the time it took me to start the car and throw it into reverse, he had covered the significant distance between us and was almost level with my door. I had a brief but unfortunate view of the back of his throat before I hurtled backwards up a steep slope. The bull pulled up short and shot me a rightfully affronted look. I suspect, had he been able to talk, he would have muttered some very unflattering words. To say I was decidedly rattled, deeply regretful and suitably chastened would be an understatement.

That night, the heat broke, the heavens opened, and summer rolled in on thick cumulus clouds. The bull hippo was gone the next day.

Quick introduction

I have had many other hippopotamus sightings, which have been more interesting or even more dangerous than the sunscreen incident (we were, after all, in a car and able to move away). Yet that moment still stands out in my mind as the most spectacular display of power from a hippopotamus I have witnessed – for the sheer speed with which the two-tonne bull went from dozing to full-on gallop.

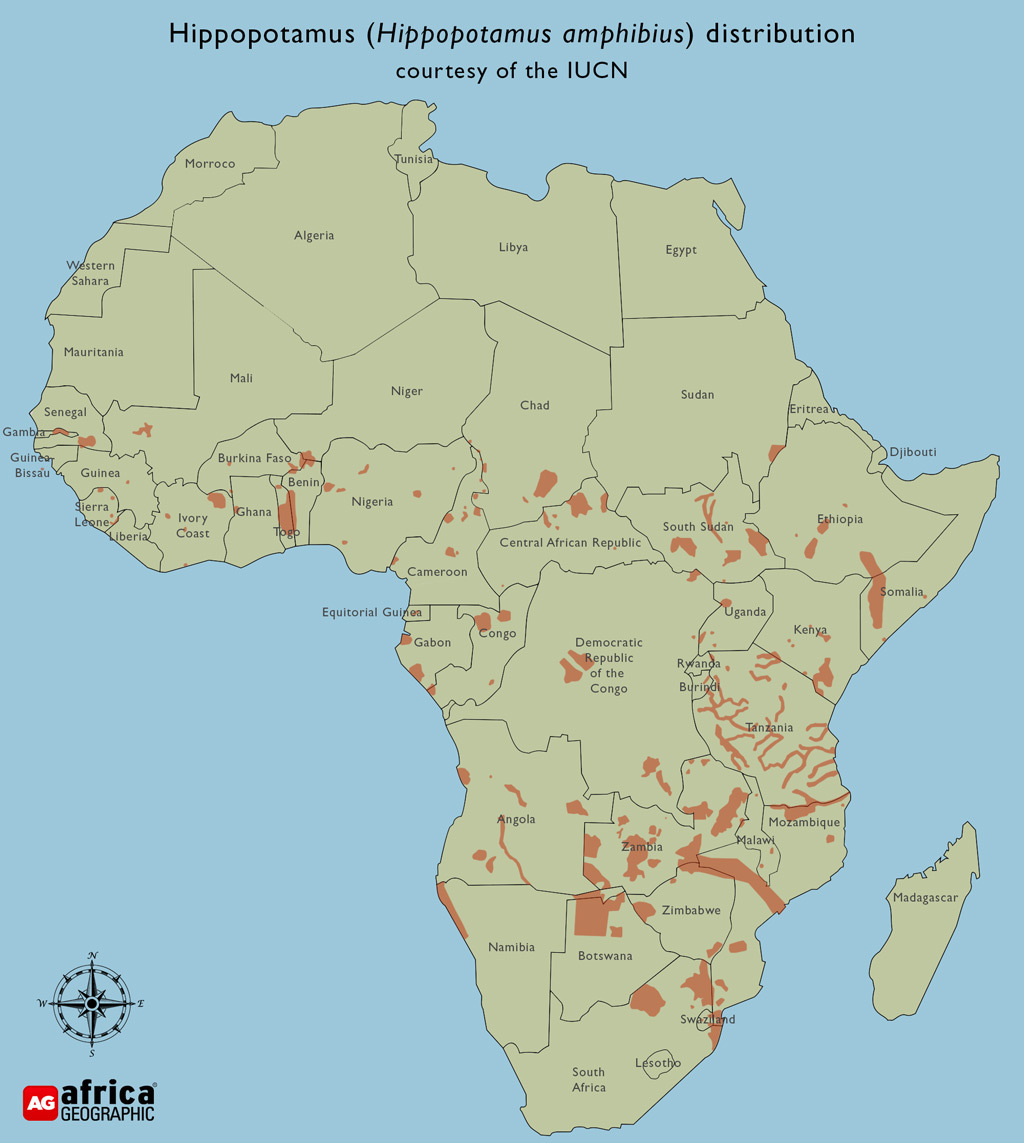

As one of the largest land mammals in the world and distributed across most of sub-Saharan Africa’s waterways, the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) probably needs little in the way of introduction. These semiaquatic behemoths prefer to spend the vast majority of their days (sometimes 16 hours or more) in the water, emerging at night or on cloudy days to graze. Despite this hydrophilic existence, hippos are surprisingly poor swimmers. They prefer to wallow in the shallows where they can stand on the river floor and move through the water by trotting or leaping along the bottom. Their dense bones confer a high specific gravity which allows them to counteract the buoyancy of the water – but this also means they cannot float.

Their specially designed skulls align the ears, eyes and nostrils on the top of the head, so these sensory organs can protrude above the surface while the hippo remains otherwise submerged. When submerged entirely, the muscles around the ears and nostrils constrict and fold to seal off to keep the water out. A hippo can hold its breath for around five minutes due to a slowed metabolism but must regularly emerge to replenish its oxygen supplies.

Though this aquatic existence confers several advantages, there is one significant trade-off: a hippo’s skin is extremely sensitive to the sun. Most people by now are familiar with the hippo’s “blood sweat” – a pinkish substance secreted onto the skin that is not blood at all but rather a specialised sunscreen. The two pigments – hipposudoric acid and norhipposudoric acid – also have antimicrobial properties to help guard the skin against infection.

Quick facts

| Mass: | Males: average 1, 500kg (up to over 3,000kg) |

| Females: average 1,300kg | |

| Shoulder height: | 1.30 – 1. 65m |

| Social structure: | Territorial males and pods of females and offspring |

| Gestation: | 243 days (eight months) |

| Life expectancy: | Up to 40 years |

| Conservation status: | Vulnerable |

Like a fish to water

The hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibious) is one of two living members of the Hippopotamidae family. The second member is the endangered pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis), native to the forests and swamps of West Africa. Several extinct members of the Hippopotamidae, some almost identical to the present-day species, once dominated the river systems across Europe and Asia (including the River Thames!). There were also at least three species of Malagasy hippos, one of which only went extinct roughly 1,000 years ago, which coincides with the arrival of humans on the island.

The hippopotamids’ closest relatives are the cetaceans – whales and dolphins. The two groups likely split from the other artiodactyls (like ruminants) around 60 million years ago and then diverged from a common semiaquatic ancestor some six million years later. The cetaceans eventually evolved to become fully aquatic, while the hippopotamids remained dependent on access to land.

Two (or more) hippos in a pod

Compared to other large land-dwelling mammals in Africa, the social interactions between hippos are challenging to study – even distinguishing young males from females is impossible when only their heads are visible. As a result, it is highly likely that there are nuances to their behaviours and social structures yet to be unravelled.

What we do know is that when water and space are plentiful, hippos form small associations of up to 15 or more individuals, known as schools, pods or, somewhat facetiously, bloats. These family groups typically consist of a territorial bull, cows, and their offspring, and mother-daughter bonds are deep-seated and may persist over a lifetime. Young males may be tolerated around the dominant bull, provided they behave submissively around him. They will often gather in small bachelor groups before eventually striking out on their own to claim a territory when they are around seven to eight years old.

Hippos do not adopt a social approach for nocturnal feeding forays, and most prefer a night of solitary snacking (where they may consume over 50kgs of grass in an evening). Interestingly, the territoriality of the bulls does not seem to extend to their land-based life, and researchers now believe that the middens are not territorial as previously thought. Male territoriality revolves around mating rights, so the region he defends in the water and along the riverbank may vary and does not extend to foraging beyond the river.

When space is at a premium (such as during the dry season when available water is limited), hippos may pack together in their hundreds. Still, they do so with seemingly great reluctance, and fights are a regular occurrence.

Frolicking hippos

Hippos may breed throughout the year, though there is usually a peak in calving during the wet season. Mating usually takes place in the water, and the female is forced to snatch quick gasps of air before the male dunks her back under the surface. Conception is followed by an eight-month gestation and the birth of a calf that may weigh up to 50kg. (It is worth considering how short this gestation period is compared to other mammals. In terms of size comparison, both rhino species give birth to calves of a similar size but their gestation period is almost double that of a hippopotamus. Even humans have a longer gestation.)

The hippo mother gives birth on her own in a quiet pool of water, and the calf instinctively strikes out for the surface immediately. The pair remain isolated until the enchanting little calf is old enough to be introduced to the rest of the pod at around a month old. As the calf grows, it becomes more confident and playful, often engaging in wrestling matches with other calves of a similar age.

Hippopotamus mothers are highly protective of their young, and hippo calves have few natural predators – generally, only lions and large spotted hyena clans attempt to hunt them. Even the massive crocodiles that share the rivers and pools are reluctant to attract maternal ire. However, one aspect of hippo behaviour that often shocks witnesses is the rare instances of infanticide. This is typically committed by the dominant bull during a territorial disruption or in times of stress, and the mother is seldom able to prevent it.

Speaking hippo

Naturally, visual communication between individuals is inevitably reasonably limited in the murky underwater environment. As a result, much hippo communication is vocal, with a laugh-like grunt being perhaps the most well-known of their vocal repertoire. However, few people realise that aside from the above surface grunts, roars, bellows and shrieks, hippos also communicate underwater. Studies show that up to 80% of hippo vocalisations are made below the surface. Some of these sub-aquatic songs are very similar to the high-pitched calls produced by whales.

Visually, the famously wide yawn is perhaps the hippo’s most notorious body language cue. The joint of the jaw is situated far back in the skull, and the orbicularis oris (the muscle we all have around our mouths) is folded in such a way in the hippo that, at full stretch, it can open its mouth almost 180 degrees. This serves to reveal an intimidating set of tusks, particularly in adult males, and should usually be interpreted as a threat display. The lower canine tusks curve upwards and can grow over 50cm in length, while the lower incisors present a forward-facing barrier of spears. The tusks are used as offensive weapons, predominantly when two bulls fight.

Fights between territorial males become more common when available water starts to shrink during the dry season. These clashes can be ferocious and fatal if one party does not back down. The vanished bull is sent packing, which, when water is scarce, can be a death sentence in the hot sun due to their sensitive skins.

The most dangerous animal in Africa?

These fearsome tusks are feared by all who encounter them, including people. The hippo is often touted as “Africa’s most dangerous animal” and the one that “kills the most people on the continent”. Both of these statements are distinctly unfair and demonstrably false. For a start (though admittedly somewhat pedantically), malaria-spreading Anopheles mosquitoes are also animals and indirectly kill up to half a million people every year. Furthermore, crocodiles likely kill just as many, if not more, people as hippos, but the bodies are frequently not found, and the victim disappears without a trace.

That said, hippos do earn their dangerous reputation. They can be aggressive and are massive, well-armed animals capable of doing significant harm. And unless you happen to be Usain Bolt, they can outrun you. Yet even this needs to be considered in context. Hippos are aquatic animals, and humans are dependent (and more populous) around water. Hippos feel safest in the water and are unlikely to bother people when fully submerged. It is when people come between them and their place of safety (or a calf) or, like my bull, during the dry season when space is at a premium, that they are most likely to attack. Staying out of their way is the best course of action. However, unfortunately, this is simply not possible for many people dependent on the river systems and living without running water.

Caught up in the tide

Of course, as dangerous as hippos can be to people, mankind too has wrought destruction on their species, and they now occupy just a fraction of their historical range. At present, the IUCN estimates there are somewhere between 115,000 and 130,000 Hippopotamus amphibius in Africa and lists their conservation status as “Vulnerable”. Though the assessors have listed the overall population trend as stable rather than decreasing, there are still many parts of Africa where hippo numbers have declined precipitously. Their close relative, the pygmy hippopotamus, is listed as “Endangered”, and there are believed to be fewer than 2,500 remaining.

The main threats facing the hippopotamids are habitat loss (as is the case for all large African mammals) and poaching for their tusks, valued in the ivory trade. They are also frequently victims of bushmeat poaching.

Yet, like other large mammals such as elephants and rhinos, hippos are important ecosystem engineers. The copious amounts of dung flung into the water by their swishing tails (much to tourist delight) provides nutrients to the many aquatic species that inhabit the waterways of Africa. Furthermore, their movement through channels and along the riverbed helps prevent a build-up of silt and moribund material, improving the river’s flow.

The greatest of beasts

When watched from a safe and comfortable distance, hippos are fascinating and delightful animals. They are also powerful, speedy and deserving of absolute respect. From the charming little calves and placid cows to playful adolescents and awe-inspiring bulls, there is something profoundly intriguing about the knowledge that we still have so much to learn…

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()