Authentic African wilderness

The Greater Kruger is a giant among conservation landscapes in Southern Africa, standing alongside renowned destinations like Botswana’s Okavango Delta and Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve in its iconic status and vast offering for safari goers.

The complement of Greater Kruger to Kruger National Park and surrounding private reserves creates one of Africa’s largest protected areas. At the heart of the Greater Kruger vision is that conservation can drive the region’s economy, resulting in thriving landscapes for wildlife and people.

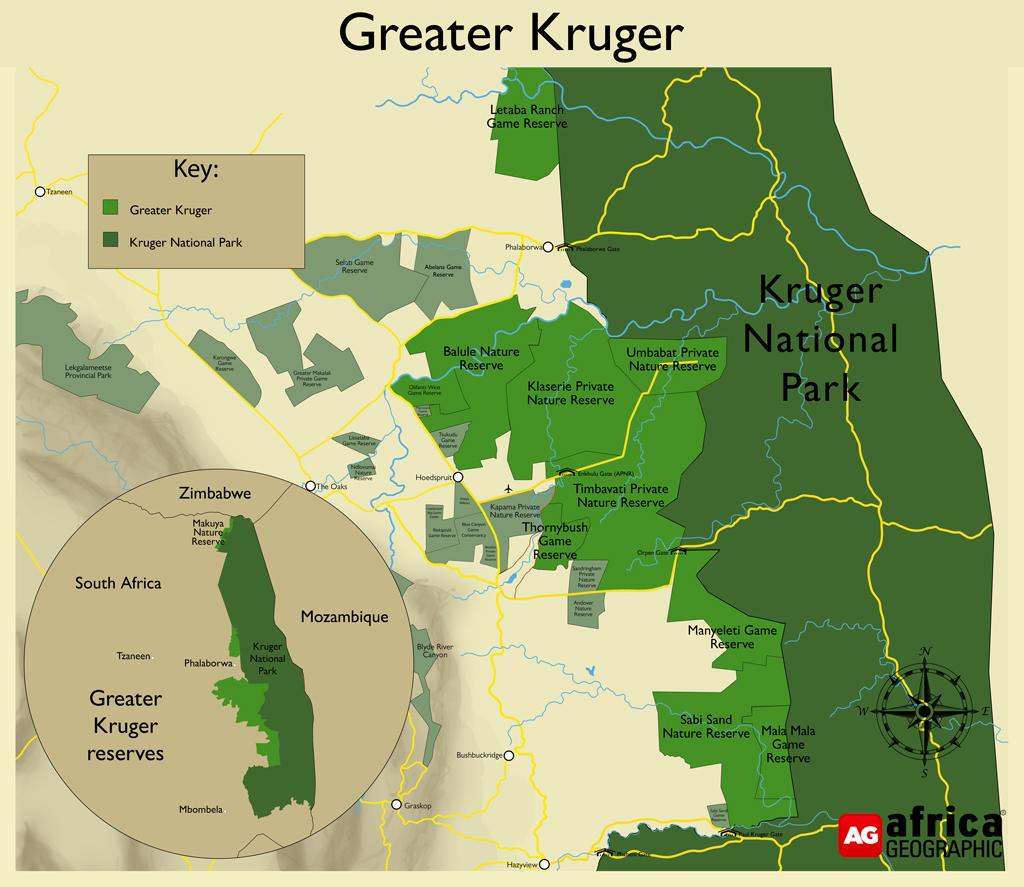

What exactly is the Greater Kruger?

Greater Kruger refers to the various private and community game reserves adjacent and open to the western boundary of South Africa’s Kruger National Park. Cooperating across boundaries, Greater Kruger’s partner reserves — Sabi Sand, MalaMala, Timbavati, Klaserie, Umbabat, Balule, Thornybush, and the community-owned reserves of Manyeleti, Letaba Ranch, and Makuya — have committed to collaborate with the Kruger National Park to create a managed conservation landscape that’s almost the size of Rwanda.

Over 4,000 private individuals hold some stake in the various private reserves that comprise Greater Kruger. Historically, many were predominantly marginal agricultural properties and consumptive-use hunting farms that transitioned to conservation and began managing their lands primarily for wildlife rather than livestock. In 1993, many of these private owners agreed to remove the fences between their reserves and the Kruger National Park, creating the Greater Kruger landscape.

Historically, community reserves have received minimal investment compared to other private reserves. The exception is MalaMala due to its unique history—its private ownership was transferred to the Nwandlamhari community in a landmark deal in 2013.

The Boundless landscapes of Greater Kruger

Spanning the Sand, Olifants and Limpopo River systems, Greater Kruger comprises woodlands, wetlands, and grasslands. The Greater Kruger region features a diverse mosaic of landscapes and vegetation types. These ecosystems support abundant wildlife, forming one of Africa’s richest biodiversity hotspots.

The terrain varies from flat plains to gently rolling hills, with some areas featuring rocky outcrops and ridges that provide shelter for smaller mammals and reptiles. Vegetation in Greater Kruger mirrors the broader savannah biome, with northern regions dominated by hardy mopane woodlands along lower-lying areas, characterised by their resilience to dry conditions and essential role in feeding elephants and other browsers. Moving southward, the landscape transitions into mixed Combretum woodlands, where bushwillows and marulas thrive alongside open grasslands, creating ideal habitats for grazing herbivores and the predators that follow them. Along river courses and seasonal drainage lines, lush riverine forests of jackalberry, sycamore fig, and fever trees create shaded, fertile corridors teeming with birdlife and aquatic species. These reserves also feature iconic Lowveld vegetation, including scattered baobabs and granite koppies dotted with aloes and other drought-tolerant plants. The interplay of these landscapes and vegetation types forms a rich tapestry of habitats that supports an extraordinary diversity of wildlife.

Healthy ecosystems sustain tourism by supporting wildlife, but even more importantly, provide essential services like water regulation and purification for wildlife and human populations. Rivers and wetlands in Greater Kruger act as natural filtration systems, providing cleaner water and managing water flow, which is crucial for agriculture, drinking water, and sanitation outside the park. Greater Kruger’s forests, grasslands, and wetlands also sequester carbon, helping to mitigate climate change.

The abundant wildlife of Greater Kruger

Greater Kruger’s woodlands, wetlands, and grasslands provide critical habitat for an extraordinary array of wildlife, with its open system enabling fauna to move between the national park and private and community reserves.

Iconic species include the Big Five—lion, leopard, elephant, rhino, and buffalo—alongside cheetahs, wild dogs, and hyenas. Its diverse habitats support giraffes, zebras, antelope species like kudu and impala, and smaller mammals such as honey badgers and porcupines. Rivers and wetlands attract hippos, crocodiles, and abundant birdlife, including eagles, hornbills, and kingfishers. Reptiles like pythons and monitor lizards are also common. This rich biodiversity thrives in Greater Kruger’s well-preserved ecosystems, making it a premier destination for wildlife enthusiasts and conservation efforts.

Significantly, the north-south shape of the Kruger National Park is not optimal for seasonal wildlife migrations, so the additional range provided by the reserves on the western boundary of the national park makes an important difference to the functioning of the ecosystem.

While other protected areas in Africa—like the Serengeti National Park, Maasai Mara National Reserve, and Etosha National Park—are renowned for specific aspects (the Great Migration in Serengeti and Maasai Mara, or the stark landscapes of Etosha), Greater Kruger’s all-around offerings combine large-scale wildlife conservation, visitor accessibility, historical significance, and various ecosystems, making it unique in the African context.

Large mammals like carnivores and elephants play a critical role in maintaining Greater Kruger’s ecosystem and the benefits it provides. As landscape architects, elephants create clearings in wooded areas as they move around and feed, which lets new plants grow and forests regenerate naturally. They also disperse their dung and tree and other seeds over vast distances, promoting healthier vegetation. Meanwhile, predators like lions, cheetahs, and wild dogs help balance the ecosystem by keeping herbivore populations healthy and providing food for scavengers like hyenas, vultures, and smaller predators that recycle nutrients into the ecosystem.

Visiting Greater Kruger

Not all parts of Greater Kruger are equal or equally accessible to visitors. Visiting the Kruger National Park is different to visiting Greater Kruger private and community reserves. While they share a common management blueprint, each protected area has its social and conservation history and offers a distinctive safari experience.

Inspired to embark on your own African safari adventure in Greater Kruger? Check out these amazing safari ideas to Greater Kruger here.

Inspired to embark on your own African safari adventure in Greater Kruger? Check out these amazing safari ideas to Greater Kruger here.

Most private reserves are supported by private funding through a world-renowned high-end tourism market. The reserves of Greater Kruger limit visitor access to overnight stays at exclusive lodges with no self-drive and few self-catering options.

Relatively high prices and strict access control for private reserves in the Greater Kruger result in low visitor numbers compared to the neighbouring Kruger National Park. They also offer off-road driving (by experienced guides), night drives, bush walks and other activities that guarantee memorable wildlife encounters and experiences for those who choose and can afford to visit them. And they have become a critical band of protection for the Kruger National Park, helping to counter wildlife crime.

Conserving the most valuable assets of Greater Kruger

Regarding the brass-tacks management of Greater Kruger, the Associated Private Nature Reserves (APNR) is responsible for managing wildlife populations, including shared efforts in monitoring species, anti-poaching measures, and habitat conservation. The APNR is an affiliation of the reserves Timbavati, Klaserie, Balule, Umbabat, and Thornybush. Together, they coordinate with Kruger National Park and act as a single body, sharing resources and adhering to shared conservation policies under the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area.

While the reserves operate as private tourism destinations, they are subject to agreements with SANParks (South African National Parks). This ensures that tourism activities like game drives and lodge operations align with conservation goals. The APNR also conducts research and collects data on wildlife dynamics, population trends, and habitat use, contributing to the overall scientific understanding of the Greater Kruger ecosystem.

Hunting does occur in some of the Greater Kruger reserves. It is governed by the South African government’s conservation authorities, such as the Limpopo and Mpumalanga provincial agencies, and specific reserve-management policies. Each year, these authorities assess wildlife populations, conservation needs, and ecological impact to determine quotas for hunting. The fees generated from hunting permits and trophy hunting contribute to conservation funding within the reserves that allow this activity. While hunting in Greater Kruger is managed with an emphasis on sustainability and conservation, it remains a controversial practice. Ethical considerations regarding trophy hunting, especially of iconic or endangered species, are often debated. There is no hunting in Sabi Sand or MalaMala.

The APNR plays a critical role in anti-poaching strategies, with dedicated ranger teams, surveillance technologies, and cooperation with SANParks to protect species like rhinos and elephants.

All reserves in the Greater Kruger landscape face wildlife and environmental crime. The Greater Kruger Environmental Protection Foundation (GKEPF) is a registered not-for-profit organisation that assists with the cooperation and coordination needed to prevent poaching and harmonize approaches to reporting, technology, and partnerships in the landscape by working with the various reserves. The Greater Kruger Area is home to South Africa’s largest rhino population. Therefore, it is a critical area for their conservation. The government and non-profit entities, including GKEPF and its partners, continue to commit funds and resources to combat these crimes.

How to visit the reserves of Greater Kruger

Sabi Sand Nature Reserve – read more

Highlight: Known for its exclusive lodges and leopards, Sabi Sand offers unrivalled encounters with these elusive cats amid rich riverine landscapes.

The conservation history of Sabi Sand began in 1898 when the area became part of the Sabie Reserve (proclaimed in 1902), which incorporated the Kruger National Park. In 1926, the National Parks Act of South Africa was passed, and private landowners adjacent to the newly proclaimed Kruger National Park were excised. Some of these landowners formed the Sabie Reserve in 1934. It became the 52,000-hectare* Sabi Sand Wildtuin in 1948. Today, the reserve’s reputation for luxury, exclusivity, and exceptional wildlife sightings, particularly leopards, makes it a sought-after safari destination globally. Sabi Sand’s lodges support conservation through tourism revenue. The reserve limits visitor numbers, and its lodges offer exclusive, immersive experiences.

Check out ready-made safaris to Sabi Sand here.

Access: Only overnight guests can access Sabi Sand. Most visitors fly to Hoedspruit’s Eastgate Airport, Kruger Mpumalanga International Airport, Skukuza Airport, or private airstrips. Experienced guides lead all activities, and lodges offer exceptional personalised service, gourmet dining, and private game viewing.

MalaMala Game Reserve – read more

Highlight: MalaMala is distinguished by its vast traversing area. It offers exclusive, crowd-free wildlife sightings and access to 20 kilometres of the Sand River.

MalaMala also formed part of the historic Sabie Game Reserve. In 1927, just after the Kruger National Park was proclaimed, 13,200 hectares between the National Park and the Sabi Sand Reserve were purchased privately and developed for tourism. In 1962, MalaMala became the first private reserve in South Africa to prohibit hunting and transition to purely photographic safaris. In a landmark land restitution deal in 2013, the ownership of MalaMala was transferred to the Nwandlamhari community. A co-management agreement allowed community ownership while maintaining the reserve’s conservation and tourism operations. The reserve is on the southeastern side of Greater Kruger, away from the busier western boundaries, and its traversing areas are carefully managed. This means sightings are exclusive, with minimal vehicle presence. Mala Mala’s lodges support conservation through tourism revenue.

Check out ready-made safaris to MalaMala here.

Access: MalaMala only caters to overnight guests. Most visitors fly to Hoedspruit’s Eastgate Airport, Kruger Mpumalanga International Airport, Skukuza Airport, or private airstrips within the reserve. All activities are guide-led, and hospitality is high-end, personal, and exclusive, with excellent game viewing.

Timbavati Private Nature Reserve – read more

Highlight: Timbavati is famous for its diverse wildlife, including predators and large herds of buffalos and elephants. It’s also increasingly recognised for linking conservation goals with socio-economic development.

The 53,396-hectare Timbavati Private Nature Reserve was established in 1956 by cattle farmers who saw more potential in wildlife conservation. When its boundary fences with Kruger National Park were removed in 1993, it was already a thriving game reserve sustained by the Timbavati River and seasonal waterholes that draw in diverse wildlife, including elephants, buffalo, and predators. Today, the Timbavati Association manages the reserve, coordinating conservation and eco-tourism efforts among 47 landowners under a unified constitution. Lodges attract local and international visitors, providing jobs for eco-tourism and supporting conservation funding through tourism and limited hunting revenue. Timbavati is known for its efforts to integrate conservation, community empowerment, and sustainability.

Check out ready-made safaris to Timbavati here.

Access: Timbavati is only accessible to overnight guests. It’s a 20-minute drive from Hoedspruit’s Eastgate Airport, and the reserve has various private airstrips. Timbavati’s luxury lodges offer conservation-oriented and immersive all-inclusive safari experiences that rival the best in the industry. There are limited self-catering exclusive-use properties and multi-day backpacking or glamping experiences where guests can explore on foot and sleep out.

Klaserie Private Nature Reserve – read more

Highlight: Known for its secluded, quiet wilderness, Klaserie is the biggest reserve in the Greater Kruger. It offers a genuinely remote safari experience with fewer crowds.

More than 50 years ago (1972), a collection of private landowners decided to pull down fences between their respective properties and form the Klaserie Private Nature Reserve. Like the other reserves that removed their fences, Klaserie became part of Greater Kruger in 1993. The reserve habitat is varied, with rocky outcrops, riverine trees, open floodplains, sandy drainage lines, and quiet dams. Game drives in the 60,080-hectare Klaserie also stand out for their quieter atmosphere. Only a few vehicles are allowed at any sighting, providing undisturbed wildlife viewing and longer observation times. Its low-density, low-impact ethic safeguards an authentic experience and helps preserve the integrity of the wilderness itself. Klaserie’s lodges support conservation and social development through tourism and limited hunting revenue.

Check out ready-made safaris to Klaserie here.

Access and Accommodation: To visit Klaserie, book into one of its lodges. Just 20 minutes from Hoedspruit’s Eastgate Airport, Klaserie is known for personalised safari experiences, with fully catered high-end options, mid-range lodges, tented camps, and exclusive-use villas.

Umbabat Private Nature Reserve – read more

Highlight: Umbabat feels like the most secret part of Greater Kruger due to its location, rugged landscape, and relatively low-profile tourism.

Established in 1956 and later expanded, Umbabat Reserve covers around 18,000 hectares between Timbavati and Klaserie on the northern boundary of Greater Kruger. It’s a quieter, more untouched corner of this vast conservation area, attracting those who seek a remote and authentic safari experience. The seasonal Nhlaralumi River, which runs through the reserve, is a lifeline for animals during the dry season and a central feature of Umbabat’s ecosystem. Umbabat has low visitor numbers and few commercial lodges. This means that sightings are rarely shared with other vehicles. The reserve operates under a federal share-block model, and land use, hunting, and conservation decisions are made collectively, with funds pooled for reserve-wide projects.

Access: Umbabat is only accessible to overnight guests. The closest airport is Hoedspruit’s Eastgate Airport. There are limited commercial lodges.

Balule Nature Reserve – read more

Highlight: Balule is ideal for visitors seeking a balance between wildlife experiences and their budget. It has several well-known, family-run camps and offers many tourism experiences and accommodation options.

Balule Nature Reserve has an interesting history that mirrors the region’s shift from agricultural land use to conservation. It covers 55,000 hectares along the Olifants River. Established in the early 1990s, Balule was a collection of privately owned farms, many used for cattle grazing. In the early 1990s, conservation-minded landowners consolidated their properties, removing fences to create a larger, contiguous conservation area. This collaborative effort marked the establishment of Balule Nature Reserve, which then joined the Associated Private Nature Reserves and dropped fences with Kruger National Park. You’ll see remnants of its farming past, but the reserve has good populations of lions, elephants, buffalos, leopards and general game. Since its formation, Balule has focused heavily on conservation, with particular attention to rhino protection. Balule is on the Western boundary of the Greater Kruger, which means it’s an important first line of defence in countering wildlife crime. There is limited hunting in the reserve.

Check out ready-made safaris to Balule here.

Access: You need to be an overnight guest to visit Balule. It’s accessible via Hoedspruit’s Eastgate Airport or private airstrips. Balule offers accommodations ranging from budget to luxury lodges, tented camps, wilderness backpack trails, voluntourism, and eco-tourism training facilities.

Thornybush Private Nature Reserve – read more

Highlight: The reserve dropped its fences with Kruger National Park in 2017, making it a dynamic piece of the Greater Kruger puzzle with excellent wildlife sightings.

Thornybush covers 14,000 hectares and has become a prominent name in the Greater Kruger ecosystem due to its luxury lodges and well-developed, exclusive tourism infrastructure. In the 1950s, Thornybush transitioned from agricultural land to a conservation-focused reserve but operated with fenced boundaries for decades, keeping wildlife within its borders. However, in 2017, Thornybush took a major conservation step by removing sections of its fencing along the western boundary with the neighbouring Timbavati Private Nature Reserve so wildlife can move freely between Thornybush, Timbavati, and Kruger National Park. Thornybush has since become deeply involved in conservation efforts, particularly in anti-poaching initiatives to protect endangered species like rhinos and supports research and monitoring programs to sustain wildlife populations and habitat health.

Check out ready-made safaris to Thornybush Private Game Reserve here.

Access: To visit Thornybush, guests need to be booked into one of its lodges. It’s accessible via Hoedspruit’s Eastgate Airport or private airstrips within the reserve. It’s known for its luxury eco-tourism experiences, hosting a range of high-end lodges that emphasise a low-impact tourism model.

Manyeleti Game Reserve – read more

Highlight: Manyeleti’s affordable safari options aren’t well known, making this a hidden gem in the Greater Kruger landscape. It borders Sabi Sand, so you may just see the area’s famous leopards at a fraction of the price.

During the apartheid era, the South African government designated Manyeleti exclusively for black visitors, which is how the reserve was resourced. And despite being established on ancestral lands of local communities, they were not allowed ownership or management roles despite having some access to the reserve. After the end of apartheid in 1994, land restitution laws enabled local communities to file land claims on areas from which they had been displaced. It’s been a rocky road to restitution, including ongoing disputes around land claims, infrastructure limitations and competition from more established private reserves. In the meantime, the Mpumalanga Tourism and Parks Agency manages the reserve as part of Greater Kruger, and visitors regularly see lions, buffalos, elephants, and leopards. Despite its rich biodiversity, the 23,000-hectare Manyeleti remains less commercialised than other reserves and focuses exclusively on eco-tourism and wildlife conservation.

Check out ready-made safaris to Manyeleti here.

Access: It’s a 45-minute drive from Hoedspruit’s Eastgate airport. Self-driving and tour operator-run day visits, and game drives are allowed. You can book overnight at the provincially run self-catering rest camp or one of the few high-end, all-inclusive luxury lodges in reserve.

Letaba Ranch Game Reserve – read more

Highlight: Letaba Ranch Game Reserve’s roads are less travelled than any others in the Greater Kruger, making it an option for the most self-sufficient travellers eager to explore new areas.

Established in the 1970s, Letaba Ranch is a 42,000-hectare area on Kruger’s border. Initially managed by Limpopo Province, the reserve was intended to reduce human-wildlife conflict by creating a buffer zone between the Kruger National Park and adjacent communities. However, the reserve faced several challenges due to limited infrastructure and resources for effective wildlife management. Community access was restricted, which created tensions as people were displaced from lands they traditionally relied on. Some of these tensions persist today. After apartheid ended in 1994, South African restitution policies allowed communities to claim land from which they had been previously removed. This led to the reserve adopting a model that includes community benefits from tourism and conservation, but it’s been a contested process, and the reserve continues to face conservation, social and security challenges. Its history reflects the broader challenges of integrating conservation with community rights and economic sustainability in South Africa’s Protected areas. Its main economic activity has been hunting.

Access: It’s close to Phalaborwa town. Self-drive day and overnight visitors can visit the reserve but expect limited infrastructure and basic campsites. There is one safari camp in the reserve.

Makuya Nature Reserve – read more

Highlight: Makuya’s Luvuvhu River gorge and mountainous landscape provide stunning vistas, unique wildlife habitats, and a rich cultural history.

Makuya Nature Reserve in the northern part of South Africa’s Limpopo Province has a unique history that intertwines with local communities, land restitution efforts, and conservation. The reserve is about 16,000 hectares and features dramatic cliffs and river gorges that provide some of the most stunning views in the Greater Kruger. It was initially part of a broader effort to establish buffer zones around Kruger National Park, protecting the ecosystem and creating sustainable land use for surrounding communities. The apartheid government, however, displaced indigenous communities and limited their rights to access and use the land. With the end of apartheid in 1994, the community reclaimed their rights to the land. Today, Makuya Nature Reserve is managed through a collaborative structure that involves the Makuya community, Limpopo provincial authorities, and conservation organisations. It is used for both trophy hunting and photographic tourism purposes. The reserve emphasises the conservation of cultural heritage sites within its boundaries, including sacred sites.

Access: Overnight and day visitors are welcome. Accessible from Pafuri Gate in Northern Kruger, Makuya offers rustic, self-catering camps and campsites, as well as eco-tourism activities such as guided game drives, walking safaris (including multi-day backpack trails), and cultural tours. While the reserve’s tourism infrastructure is modest compared to other Greater Kruger reserves, it provides an authentic, off-the-beaten-path safari experience.

Final thoughts

The Greater Kruger stands as a beacon of hope for conservation and community upliftment in Southern Africa. Its breathtaking landscapes, diverse ecosystems, and remarkable wildlife are a testament to the power of collaboration between private reserves, communities, and national parks. This iconic wilderness not only offers unforgettable safari experiences but also exemplifies the profound impact of harmonizing conservation and economic development. As Greater Kruger continues to evolve, it remains a symbol of Africa’s resilience, beauty, and commitment to preserving its natural heritage for generations to come.

Further reading

- A Greater Kruger walking safari in Big 5 country is the best way to unplug and get back to basics. Simon Espley, Africa Geographic CEO, shares his experience

- Jamie Paterson spends time with the famous leopards of Sabi Sand Nature Reserve, Greater Kruger, on a specialised leopard safari. Read more about her safari here

- Associated Private Nature Reserves (APNR), part of Greater Kruger, completed their 2021 wildlife census. We analyse the ebb & flow of results

- Check out these two epic photo galleries from safaris to Klaserie here and here.

* The commonly used 65,000-hectare area measurement for Sabi Sand Nature Reserve often includes the area measurement of MalaMala, for which we have provided a separate measurement above.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()