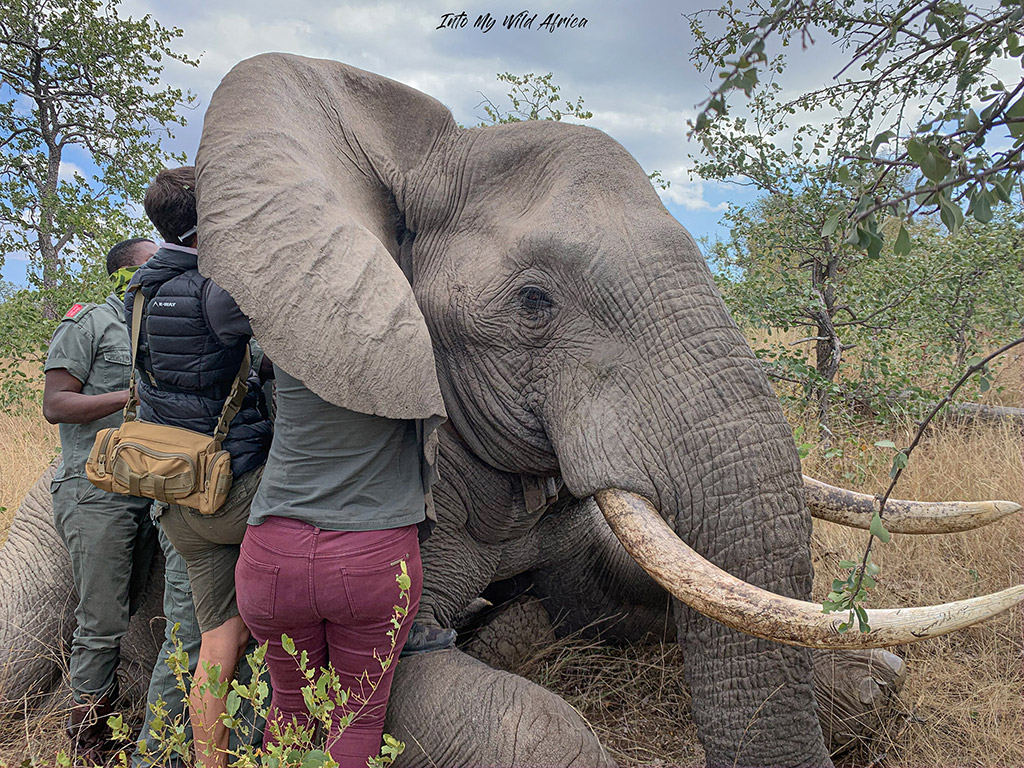

Earlier this year, Africa Geographic CEO Simon Espley accompanied the Elephants Alive team as they collared two elephants in the grounds of the Palabora Mining Company (PMC), an active copper mine on the outskirts of Phalaborwa. Simon describes how the process of collaring an elephant is both visceral and emotional. It is, by necessity, an invasive procedure, but the data gained from these few individuals can prove invaluable for the species.

But what happens when the collar has served its purpose and reaches the end of its lifespan? This was the situation the team faced with an elephant named Fortunate. Fortunate was collared in July 2015 after being chosen on the basis that he moved around the mine area and was in the right age category (25-30 years old). His movements were monitored for four years before the collar stopped working in 2019, so the plan was to remove the collar once he was found. Ideally, when monitoring individual collared elephants in large areas, they need to be found before the collar stops working so that it can be removed or replaced, but this is not always achievable in practice. Fortunate remained elusive until May 2020 when he was spotted by Eugene Troskie of Lions Place lodge. Eugene notified wildlife vet Dr Joel Alves, who advised Dr Michelle Henley from Elephants Alive. Luckily, having collared over 180 elephants, the Elephants Alive team is always ready to move at a moment’s notice – as soon as the ink on the necessary permits has dried.

Fortunate was located and darted by helicopter, and with the help of meticulous dosage control and a small ground team, he slowly folded down to rest on his chest. His chosen position forced the team to work as quickly as possible; the experienced team used a hacksaw to cut through the thick material of the collar, and the entire operation was over in a matter of minutes. Joel quickly administered the reversal drug to a thick vein behind Fortunate’s ear, and within minutes Fortunate was back on his feet, looking somewhat bemused but none the worse for the wear. As he wandered off into the surrounding vegetation, now collar-free, Fortunate could have little idea of just how valuable the information on his movements truly is (an animated representation can be viewed through the link at the end of this story).

Fortunate is one of the area’s “mine elephants” – he spends a significant portion of his time in PMC’s reserve, which is open to the Greater Kruger and surrounding Associated Private Nature Reserve. The observation that this particular tract of land seemed to have higher concentrations of elephants than surrounding areas attracted the interest of Michelle and ultimately led to multiple cross-discipline, long-term studies of elephant movements in the region. In the study now published in Science of the Total Environment, this research builds on the data of previous studies that indicated that the home ranges of elephants that utilize the land around the mine are around 59% smaller than the home ranges of elephants that do not. Thus, elephants that frequent the mine areas do not have to travel as far to meet their nutritional needs, including their necessary mineral intake.

The mining process inevitably brings minerals to the surface soils, and the study describes how varied the geochemistry of the area is as a result, with significantly higher mineral levels present in the soil, water, and vegetation when compared to surrounding areas. This, in turn, is reflected in chemical analysis of the dung and tail hair of these elephants, which indicates higher levels of cadmium, magnesium, phosphorus, and copper, among others. Phosphorus plays a particularly significant role in the movement of cows, as it is used in reproduction and lactation.

The importance of the research goes far beyond Fortunate and his pachyderm cohorts. Understanding what drives elephant movements, including the geochemistry of an area, is essential to conservation efforts and programmes aimed at reducing elephant-human conflict. While PMC is practised in dealing with elephants around the mine, other mines that have the potential to attract elephants may well not be, resulting in the potential for damage to equipment and danger to both human and elephant lives. With the ever-diminishing amount of space available to them, elephants regularly come into conflict with people throughout Africa; at certain times of the year, they are known to raid crops, causing severe damage to the livelihoods of their human neighbours. And much of this is driven by their natural instinct to seek out nutrients.

As Michelle explains, understanding what draws elephants to an area can be flipped to work out how to draw them away from undesirable areas of dense human habitation. This has the potential to save both human and elephant lives. She reports how “there have been examples where Asian elephants have been drawn away from conflict with humans because culturally, elephants are revered. It would be wonderful if Africa can implement ways to also solve potential conflict peacefully and foster human-coexistence rather than conflict with our dwindling wildlife. We have seen a 97% decline in the African elephant population in the last 100 years. Experimental research using supplements to attract elephants away from conflict is not only novel but required.”

For elephants like Fortunate, this may mean wearing a collar for a few years, but this seems a small price to pay if it helps to find new and inventive ways to reduce human-elephant conflict throughout Africa.

The removal of Fortunate’s collar and an animated representation of his movements can be viewed here. Animation video of Fortunate’s movements by Anka Bedetti and video compilation and filming by Aïda Ettayeb (Douda Aïda)

Read the full study here: “Spatial geochemistry influences the home range of elephants“, Sachs, F., Yon, L., Henley, M., Badetti, A., et al, 2020, published in Science of the Total Environment. This study was a joint effort of Elephants Alive, British Geological Survey, University of Nottingham, the Applied Behavioural Ecology and Environmental Research Unit of the University of South Africa, SANParks, Nottingham Trent University and the South African Environmental Observation Network.

SPECIAL MENTIONS

In addition to the crew from Elephants Alive, the following played a leading role in this elephant collaring day:

• Provincial permits – Dirk de Klerk of Limpopo Department: Economic Development, Environment and Tourism (LEDET)

• Neighbour permissions – Kruger National Park, Foskor, Phalaborwa Military base & Klaserie Private Nature Reserve

• Vet – Dr Joel Alves from Wildlifevets

• Helicopter pilot – Gerry McDonald

• Sponsor – Dex Kotze from Youth for African Wildlife

• Video compilation – Aïda Ettayeb (Douda Aïda)

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()