The remote Seychelles atoll of Aldabra and her giant tortoises

In 1874 Charles Darwin, along with six other eminent contemporaries, wrote to the Governor of Mauritius and its dependencies: “We the undersigned respectfully beg to call the attention of the Colonial Government of Mauritius to the imminent extermination of the gigantic Land Tortoises of the Mascarenes, commonly called ‘Indian Tortoises’…

No means being taken for their protection, they have become extinct in nearly all these islands, and Aldabra is now the only locality where the last remains of this animal form are known to exist in a state of nature.”

This was the first time – but not the last – that the intervention of scientists saved the Indian Ocean atoll of Aldabra. Now part of Seychelles, and enshrined in 1982 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Aldabra is home to the world’s largest population of giant tortoises, and as Darwin noted, the only remaining natural one in the Indian Ocean. Other Mascarene islands once had similar inhabitants; there were giant tortoises on the granitic Seychelles, Madagascar and Comoro islands; there were flightless birds on Mauritius and Réunion. Humans failed them all.

But not here.

Described by UNESCO as a prime example of an oceanic island ecosystem, Aldabra is one of the last remaining such places on our planet, a refuge of stability in a volatile world. It is so isolated and so inhospitable to humans; one photographer called it “the island that wants to kill you”.

In the late 1960s, Aldabra again came under the spotlight of the international conservation community, when the British and US governments considered developing the world’s largest raised atoll as a military base. Several scientists from the Royal Society, supported by other scientific bodies such as the Smithsonian Institution, mounted a protest, gaining public support against the development (known as the “Aldabra Affair”). Eventually, the Society was able to buy the lease to the island. A research station was completed in 1971, and to this day a permanent 15-person research team lives on the island. In 1979, responsibility for the protection of the atoll was moved to a public trust, the Seychelles Islands Foundation, which continues to manage the island.

The atoll itself consists of four main islands: Picard, Polymnie, Malabar and Grande Terre.

Picard

The most westerly of these, Picard, is the only permanently inhabited part of Aldabra. This has been the case since Darwin’s day as it possesses by far the largest and safest beach, protected by the reef some half a kilometre offshore.

Attempting landings anywhere else on the outside of the atoll, even in the calmest weather, can spell disaster; sometime in the 1920s, the Lion, carrying 200 passengers, wrecked off the south coast, a stone’s throw from the shore. All but 20 perished in the surf and on the vicious rocks that line the coast. The few who survived the wreck soon died of dehydration.

It is not only humans who made good use of Picard’s Settlement Beach. Aldabra is one of the most important turtle nesting areas in the region, and this beach is by far the atoll’s most popular nesting site for green turtles. The turtle trade was the primary reason why Aldabra was settled in the first place. This trade was not unregulated, and the lessee of the island was required to inform the Governor of Mauritius of intended catches.

However, documentary evidence shows that in the early 1900s, lessees were requesting (and presumably granted) permission to land a staggering 12,000 turtles a year – mostly nesting females and mostly taken from this one 2-kilometre stretch of beach.

These unsustainable practices continued until 1968 when a Seychelles-wide ban was brought into force. By this time, turtle populations had dwindled to a fraction of what they once were; potentially as few as a thousand across the atoll. Studies in the mid-1980s, however, showed a gradual increase in the numbers of nesting females.

In the absence of human hunting and without the pressures of invasive predators, beach destruction, and artificial lights that have so plagued other nesting beaches, the turtles began to return in increasing numbers. In 2016, some 5,700 nesting emergences were recorded on Settlement Beach alone.

A real conservation success story, and one that shows that often all that is required to allow populations to recover is not radical intervention, but merely allowing nature to take its course without human interference.

Polymnie

Northeast of Picard lies the island of Polymnie – the smallest of the main islands and the only one uninhabited by tortoises. No one knows why this is the case, but it is possible that they were extirpated by human hunting.

Whereas tortoises can migrate across the channels from island to island, the two channels that separate Polymnie – Grande Passe and Passe Gionnet – have unusually swift currents, slowing recolonisation. In addition to these two channels, Passe Hoareau in the northeast and the West Channels near the research station allow Aldabra’s massive lagoon to fill and empty twice a day.

This lagoon is some 190 square kilometres – enough to accommodate Manhattan twice over – but nowhere except the channels, scoured as they are by the ripping currents, does it get more than five metres deep.

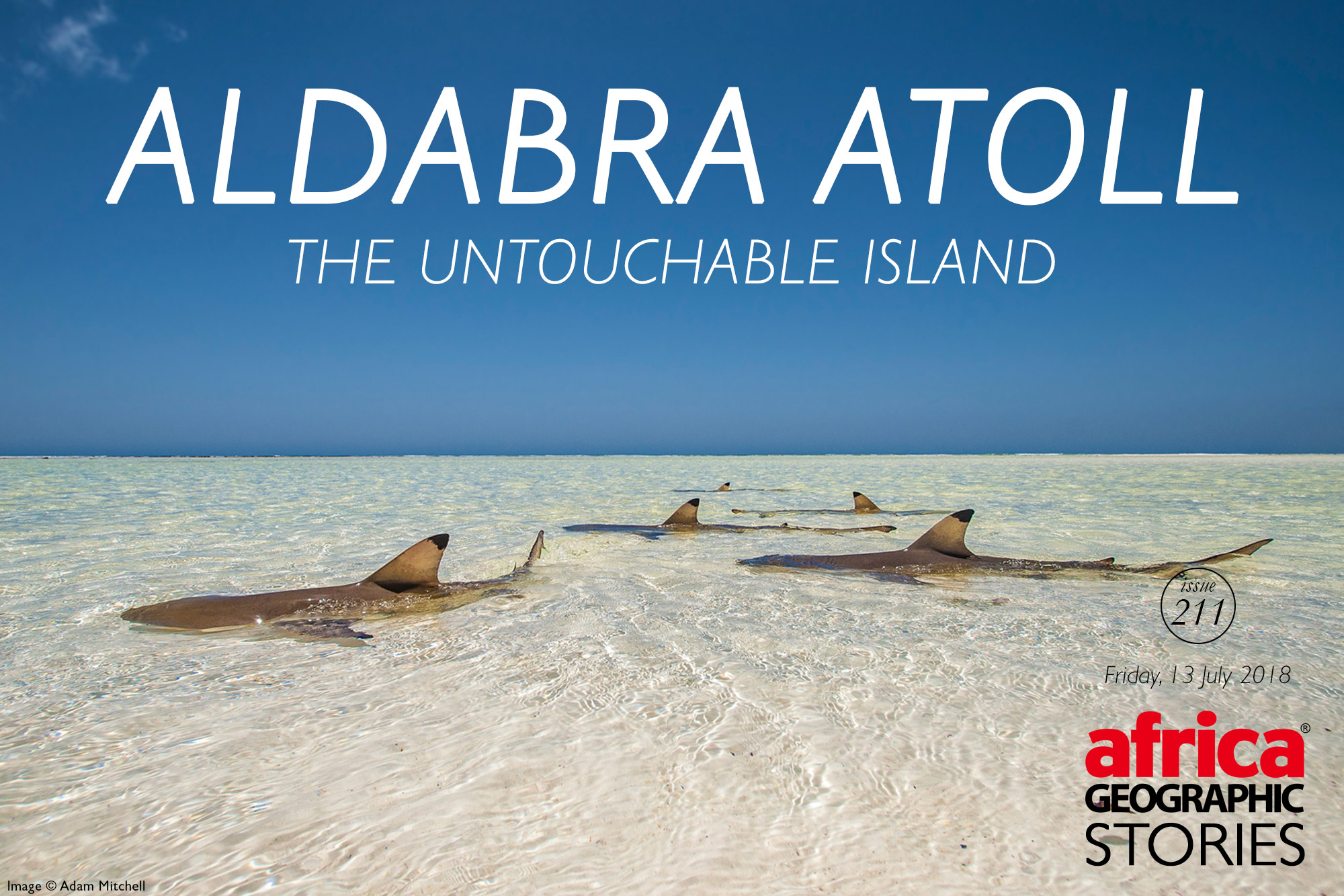

The shallow waters and fringing mangrove forests are a haven for wildlife. Hawksbill and green turtles cruise here in their hundreds threatened only by tiger sharks up to five metres in length; seabirds and waders abound. Aldabra is also home to globally significant populations of crab plovers, red-footed boobies, and possibly the world’s largest frigatebird population; it is one of only two oceanic breeding areas for flamingos, and the blue-eyed Aldabra sacred ibis (along with 11 of the other twelve land bird species) is found only here.

Fish biomass is some ten times higher here than in granitic Seychelles; the only fishing that is allowed here is closely monitored subsistence fishing by the researchers. Sharks thrive here, and the sight of massive giant groupers is common. At one of the regular marine survey sites, divers are usually shadowed by Hank, a two-metre-long potato grouper with a fascination for diver’s dreadlocks.

Pods of resident spinner dolphins are seen on almost every boat journey, and during the dry season, humpback whales and their newborn calves pass by in droves.

Malabar

East of Polymnie we find Malabar Island, which runs most of the remaining length of the north of the atoll. Malabar was the last stronghold of two of Aldabra’s endemic birds; the Aldabra warbler and the Aldabra flightless rail. The introduction of rats with early settlers, and subsequently of cats around 1900 to control the rats, spelt disaster for these two species.

Although we cannot be sure of the reason for the decline and eventual extinction of the warbler, last seen on Malabar in 1983, we do know that the impact of these two invasive mammals (the cats in particular) caused a steep decline in numbers of the rail. By this time, the Aldabra rail was the sole remaining flightless bird in the Indian Ocean, a region that was once home to such flightless birds as the dodo, Rodrigues solitaire and Madagascar’s elephant bird.

In 1999, cats were eradicated from Picard, and a rail reintroduction program was initiated, which led to great success. In less than 20 years, an initial population of 18 reintroduced birds has ballooned to over 3,000. The distinctive rising duets of these monogamous birds can now be heard all across Picard and is to many residents the ‘sound of Aldabra’.

Grande Terre

The largest of the main islands, taking up the whole southern and eastern borders of the atoll, is the aptly-named Grande Terre. Although Aldabra’s tortoises are found on Picard and Malabar (and also Ile Michel, the largest of the islets that dot the massive lagoon), it is on Grande Terre where they truly make their stand.

As on many other islands, the lack of native terrestrial mammals established reptiles as the primary herbivores. Aldabra is the only place in the world whose ecology is dominated by a single herbivorous reptile species.

Here, it is the endemic giant tortoises that have adopted this niche; and giants they indeed are, with a carapace on Picard Island reaching on average over 1.2 metres in length, and with an average weight of 250kg (the heaviest recorded wild-living Aldabra tortoise is over 360kg).

The impact the tortoises have on the Aldabra ecosystem cannot be overplayed; an entire plant assemblage of over 20 sedges, grasses and herbs, known as ‘tortoise turf’, has evolved alongside these ecosystem engineers, and their dung provides food and fertiliser for numerous other species.

Although technically herbivores, the harsh environment on Aldabra means that resources are never wasted. Toward the end of the dry season, these tortoises have been known to eat carrion, including the carcasses of seabirds and even other tortoises (in a bizarre twist of the childhood tale, Aldabra tortoises in an introduced population on Cousin Island have been known to eat non-native hares!)

Although very young tortoises are at risk from crabs, herons and pied crows, after a few years they have no natural predators, and when the sun sets after their evening grazing session, they will fall asleep where they stand.

Since the cessation of tortoise hunting, they have only two threats as adults: the sun, and sinkholes. As reptiles, tortoises must control their body temperature behaviorally. If they don’t take shelter from the hot sun in the middle of the day, they will bake to death in their shells.

Because of this, shaded areas are often crowded with tortoises, and in areas with limited vegetation, they will pack into small caves, stacked one of top of each other like nests of tables – one such cave on Grande Terre, with an opening five metres long and 1.5 metres high, was found to contain over 80 tortoises! Windswept beach trees regularly shelter over 200 tortoises. Trees and caves which have been used as shelters for perhaps hundreds of years boast this distinction with highly polished roots and rocks as a result of daily tortoise traffic.

The limestone geology of the island means that large, deep sinkholes are commonplace and these holes will often be littered with the bones and shells of tortoises who have fallen to their deaths, or who were unable to climb back out having mistakenly reached too far for overhanging vegetation.

Unlike granitic Seychelles (the ‘inner’ islands), Aldabra was never part of the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, whose tectonic migration over 200 million years ago left the granitic islands in its wake. Aldabra is much younger, and at approximately 2 million years old is a relative newcomer to the region. This comparatively short time for colonisation, along with its isolation and harsh environment, is reflected in its relatively low terrestrial vertebrate diversity, consisting mostly of birds and bats (who were able to fly to the island), and small reptiles (one gecko and one skink species) who were likely brought accidentally on floating rafts after storms.

But the question might reasonably be asked: “How did the tortoises get there?”

It would be hard to imagine a 200kg tortoise rafting on floating vegetation, and surely they didn’t swim all that way? Well, likely, they did indeed swim. In 2004, a tortoise believed to have come from Aldabra trudged up out of the sea on a beach in Tanzania, having travelled a distance of over 740km. It was even possible to estimate, from the size of the barnacles covering the legs and lower carapace, that the tortoise had been at sea a minimum of 6 to 7 weeks!

Tortoises are fantastic island colonisers. As Darwin noted, before the arrival of humans, perhaps 20 species and subspecies were present on islands in the Indian Ocean, not to mention the famous Galapagos populations in the Pacific.

Heavy as they are, their lungs are located at the top of the carapace, ensuring the tortoise will float upright. They can survive without food or water for up to 6 months, and their oxygen requirement is so low that on Aldabra, they have been seen to sleep with their heads underwater. These factors amount to a perfect storm for a coloniser!

Although a 3-day survey on Picard in 1898 failed to locate a single tortoise due to over-hunting, their numbers have now reached a healthy and stable population of approximately 100,000 individuals – the largest giant tortoise population in the world, and about five times that of the Galapagos population.

Without these ecosystem engineers, the ecology of this unique island would be very, very different, and without the legacy of protection initiated by Darwin almost 150 years ago and continued by Aldabra’s protectors today, the world would have lost one of its few pristine islands and the only remaining home of these magnificent reptiles.

Aldabra’s history tells us that we can have a profound influence on the trajectory of our natural world, both for good and evil. This is particularly pertinent now as despite its protected status there is now a new insidious threat to Aldabra. Large amounts of plastic debris now wash up on Aldabra’s beaches from as far away as Australia, India, China and Malaysia, killing birds, turtles, tortoises and marine mammals.

In a world of rapid change, biodiversity loss, habitat destruction and over-exploitation of resources, we sometimes despair of there being the hope of a bright future. We wonder whether there are any places left on Earth that have remained stable and we wonder what we can do to protect and preserve our natural treasures. Aldabra is proof that with enough willpower we can save Earth’s special places. But the ongoing plastic threat shows us that the only way to indeed do so is as a global community.

For accommodation options at the best prices visit our collection of camps and lodges: private travel & conservation club. If you are not yet a member, see how to JOIN below this story.

Also read: Extinct snail rediscovered in Seychelles

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

April Burt

April Burt

April Burt is currently studying for her DPhil at the University of Oxford after spending the past eight years in conservation management and research positions in the western Indian Ocean region. This included working in senior scientific roles for GVI Seychelles, Nature Seychelles and lastly as the scientific coordinator for Aldabra atoll, a marine UNESCO World Heritage Site. April has led expeditions and teams now for many years and is now the leader of the Aldabra Clean Up Project, a collaboration to clean one of the largest atolls in the world of marine plastic pollution. She is also a member of the IUCN commission on ecosystem management in the island ecosystems specialist group, and she has authored or co-authored several scientific publications specialising in both marine and terrestrial tropical habitat conservation.

Adam Mitchell

Adam Mitchell

Adam Mitchell is a biologist and photographer with a particular interest in herpetology, island ecosystems, and field data management. He has lived and worked throughout the Caribbean, and more recently spent three years managing a remote field lab in the Kalahari desert, and 18 months stationed on the remote Aldabra atoll. He counts himself lucky to be among the handful of photographers fortunate enough to spend more than a few days on Aldabra and perhaps the only one in recent years to be able to catalogue a full year there. You can follow him on Instagram or visit his website.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()