RUNNING A PARK AT THE SHARP END OF CONSERVATION

‘The current buzzword in the travel industry is “experiential”. But it’s been used to death. It’s old. It’s dull,’ says renowned safari guide Michael Lorentz. ‘A colleague of mine in Kenya, Peter Silvester, was talking about making spears the old way by smelting them in the sand, and other off-piste stuff, and he said to me, “Mike, screw it. Experiential travel is for the birds. What we want to be doing is experimental travel.”’

Lorentz recently returned from Zakouma National Park in Chad, where he was guiding guests for the first time. Chad isn’t on the romanticised safari circuit like Kenya and Tanzania. Chad’s recent political instability means the country’s tourism infrastructure is almost non-existent. But that’s what attracted Lorentz: a sense of the unknown – and the fact that Zakouma was being managed by African Parks, an organisation he thinks of as Africa’s conservation heroes.

2. Northern carmine bee-eaters on a river bank.

3. This Lion has its sights locked on prey.

4. One of Zakouma’s newly trained and equipped rangers, a determined force against poachers. All images ©Michael Lorentz

‘The guests I took to Zakouma were hardcore safari enthusiasts, each with over 20 safaris under their belt. Doing something like this attracts guests looking for something beyond the infinity pool. Granted, we weren’t going into a war zone. We weren’t on the frontlines of anti-poaching patrols like the rangers are. But it’s not a family holiday. It’s incredibly remote. It’s uncomfortably hot. The Tsetse flies were so vicious in some parts that between eight and fifteen were biting you at one time – there were moments I wished I had a beekeeper’s suit. But it’s a privilege to be able to go to a place that has that kind of experience. It’s a real adventure.’

And Lorentz’s guests agree. Despite all of the incredible African trips they have under their belts, they said Zakouma was the safari highlight of their lives.

Tourism professionals spend so much time trying to avoid any hardships for their guests that the safari experience loses its wild edge. But there’s a breed of traveller who wants to go places where they are not mollycoddled and where authenticity isn’t manufactured. ‘We are at such a scary period in history. Everything is frightening. We need to retrain people to be adventurous,’ says Lorentz. ‘We may have thought that by taking away risk, we have created a happier life. But it’s not true.’

Some travellers want to go places where authenticity isn’t manufactured

Lorentz is quick to point out that the tourism industry would never put clients in harm’s way, but that it’s people’s perceptions of risk that need to be challenged. It rings true when it comes to tourists’ perceptions of Africa. Thousands are cancelling trips to the big safari hubs like Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa because of the Ebola outbreak, even though these regions are so distant from the affected areas that saying one is cancelling a trip to South Africa because of an Ebola outbreak in West Africa, is like cancelling a trip to Florida because of an outbreak in Alaska.

2. Ablution facilities at one of Zakouma’s fly camping stops.

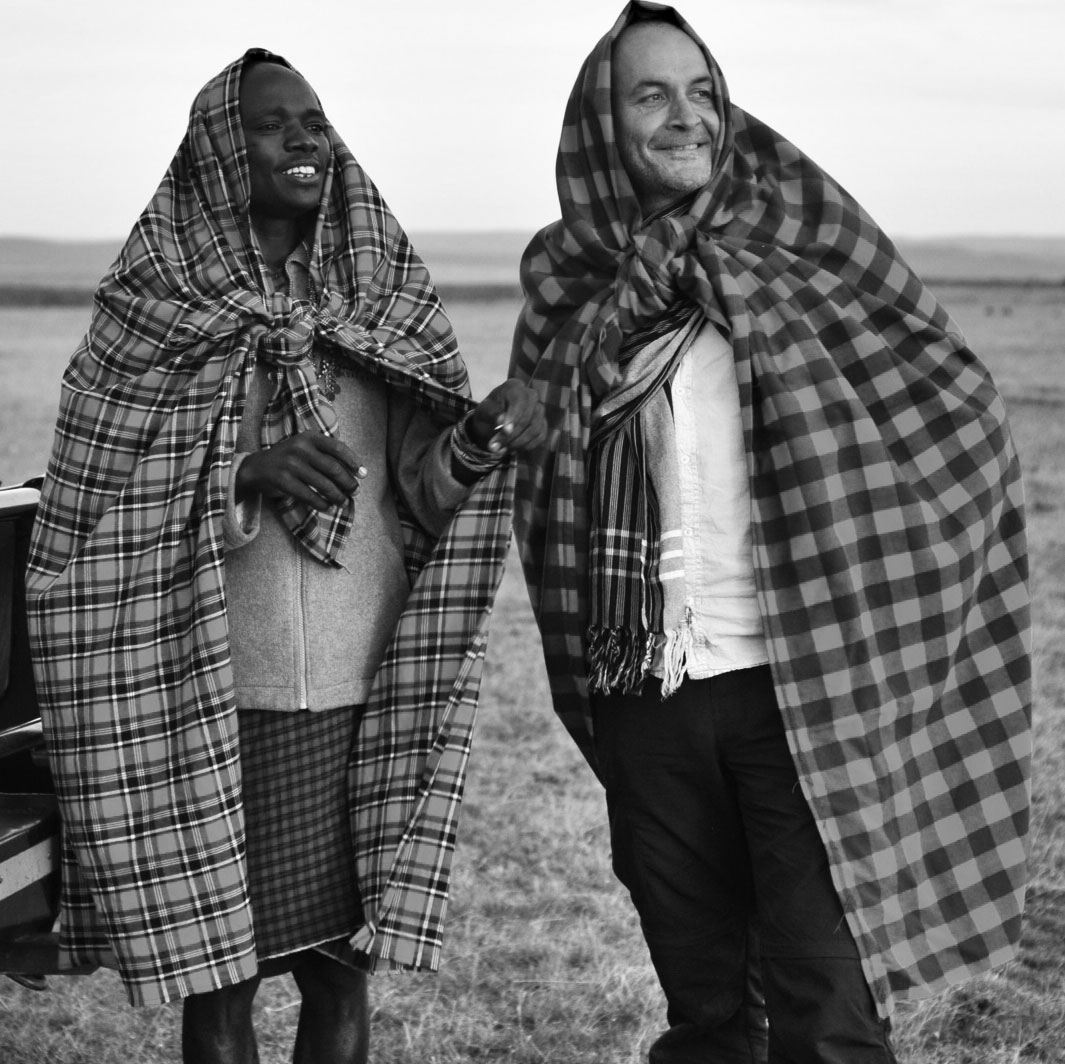

3. Winding down after a long day of walking.

All images ©Michael Lorentz

But if a tourist is willing to be a little more adventurous, the reward is far greater, and for a guide like Lorentz, who is extremely well-versed in conservation issues, it is doubly rewarding because it enables him to find out what is happening on the edge of conservation and beyond, which is where African Parks operates.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? Find out more and book your African Parks safari.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari camps (lodges and campsites) where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? Find out more and book your African Parks safari.

‘In many parts of Africa, conservationists are at war,’ says Lorentz. ‘And African Parks are going into the hardest areas knowing how important they are to conservation. Governments throughout Africa have struggled to manage their parks. But the Chadian government had the foresight to let African Parks manage Zakouma. And the results speak for themselves. The park would hardly have any elephants left without them.’

Zakouma is considered one of the last strongholds for central African wildlife, but demand for ivory has sky-rocketed over the last decade, and Zakouma’s elephant population has suffered terribly under the poacher’s gun. An estimated 4 300 elephants in 2002 were reduced to 450 by 2010.

The massacre of Chad’s elephants is nothing new. Going back two centuries, Sudanese gangs mounted on horseback regularly made their way to the region to hunt elephants using spears. They would load the ivory onto camels and donkeys and return to Sudan with the loot. ‘Today, they use AK 47s and belt-fed machine guns. There have been massacres of 60-80 elephants at a time,’ says Zakouma National Park manager Rian Lubuschagne. ‘In Chad, the elephants are known for moving in tight groups for mutual protection. It was originally a defence against the horseman with spears who would have to separate individual elephants to kill them. But that dense grouping has become their greatest downfall. It now makes it easier for mounted poachers to corner the elephants, herd them in a direction, and ambush them with machine guns, shooting into the group.’

2. Take off from one of Zakouma’s many airstrips, which have proved vital in the fight against poaching. ©African Parks

Zakouma’s elephant population is now stable at just over 450 but might have been wiped out if African Parks hadn’t taken over in 2010. It wasn’t easy to convince Chad’s government to give them the sole mandate of managing the park – and to do so beyond the usual five-year project basis. ‘This had to be for the long term,’ says Labuschagne, ‘But steadily, once the government started seeing results and how we were working with the Chadians as partners, they started accepting it. They are very serious about it now. President Déby is driving it, and we get their full support.’

But how did they turn it around? Labuschagne explains that one of the keys was studying the history of Zakouma, particularly where and when the elephants were most threatened. It became clear that, for about three months during the wet season, when the park closed down, there was intensive poaching. The elephants moved in a very wide area to try and escape – moving up to 100 kilometres beyond the periphery, but it was here that poachers found it even easier to pick off the herds. The key was for African Parks to stay in the park and conduct operations for 12 months of the year.

12 airstrips were opened to deploy rangers and conduct extensive aerial patrols

‘If you look out here now, it is one big lake. We’re on an island. We can just get to the headquarters with a 4×4 tractor,’ says Labuschagne. To resolve this, one of the first things they did was build an all-weather airstrip right next to the park. With good planning and the stockpiling of food, equipment and fuel, they could operate year-round. They also opened 12 small airstrips at key places throughout the park, and within the first year, they could follow the elephants as they moved. ‘10 to 12 satellite collars were fitted to elephants so we could track the main herds. This and the airstrips allowed us to plan and execute our ranger deployment and perform aerial patrols with efficiency.’

One of the other major issues was that rangers were informing locals – and poachers directly or indirectly – about their patrol areas and the location of the herds. African Parks eliminated this by withholding all information about upcoming patrols from the rangers until they were at central command and ready to be deployed. This way, they had no opportunity to inform anyone.

Putting rangers on horseback meant they were on a par with poachers

Approximately half of the rangers are now on horseback. This puts them on a par with poachers regarding ground operations, and the horses are even better utilised during the wet season when vehicles cannot negotiate the park. It also allows them to cover larger distances, carry more provisions and conduct patrols over a longer period. Thanks to the donation to African Parks of a thoroughbred stallion to breed with local mares, their horse stock has been improved. Also, as a contribution to community understanding and enrichment, the sire services have been extended to the local people’s horses.

2. Lion cubs at rest. ©African Parks/Nuria Ortega

3. A giraffe and leopard cross paths on a Zakouma river bed. ©Michael Lorentz

4. A male lion ventures into the water at one the author’s “infinity pools”. ©Michael Lorentz

But Zakouma is still probably the most dangerous park in Africa to be a ranger. ‘They have lost 23 rangers since the 90s in conflict with poaching gangs from Sudan,’ says Labuschagne. In September 2012, six Zakouma rangers were murdered while they were at morning prayer in what is considered a reprisal attack by poachers. French ex-military and ex-police Special Forces officers now conduct training.

This story of Zakouma is what Michael Lorentz wanted his guests to know and appreciate. Lorentz’s infinity pool is of a different sort. It is a place in Zakouma, a natural water point abundant in wildlife called Tinga Junction. ‘Sitting here for hours, with no weapon, no vehicle backing you up, you are just one of the elements,’ he says. ‘Creatures are reacting to you – your movements, your body language. That’s being in nature. That’s very hard to achieve at a typical infinity pool.’

RESOURCES

Blown away by Zakouma National Park – a trip report from a visit to Zakouma

Celebrating Zakouma National Park – a celebration of the Zakouma National Park’s creation

Keeping up with the Kordofans – more about the Kordofan giraffe

Contributors

MICHAEL LORENTZ is passionate about wildlife, wilderness and elephants in particular. Born in South Africa, he knew from an early age that his true vision and happiness would lie in Africa’s wild places. A passionate and award-winning photographer, Michael’s work has been featured in several publications, as well as at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington DC. Having guided for 26 years, this remains his first professional love, conducting safaris throughout Southern, East and Central Africa.

MICHAEL LORENTZ is passionate about wildlife, wilderness and elephants in particular. Born in South Africa, he knew from an early age that his true vision and happiness would lie in Africa’s wild places. A passionate and award-winning photographer, Michael’s work has been featured in several publications, as well as at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington DC. Having guided for 26 years, this remains his first professional love, conducting safaris throughout Southern, East and Central Africa.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, sometimes drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, sometimes drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()