- Africa’s wildlife energy flows have dropped by over one-third since 1700.

- Ecosystem functions declined sharply as birds and mammals lost ecological power.

- Agricultural conversion reduced ecological power by about 60% across sub-Saharan Africa.

- Protected areas retained nearly 90% of animal-driven ecosystem functions and energy flows.

- Megafauna-driven grazing, browsing and nutrient cycling collapsed outside protected landscapes.

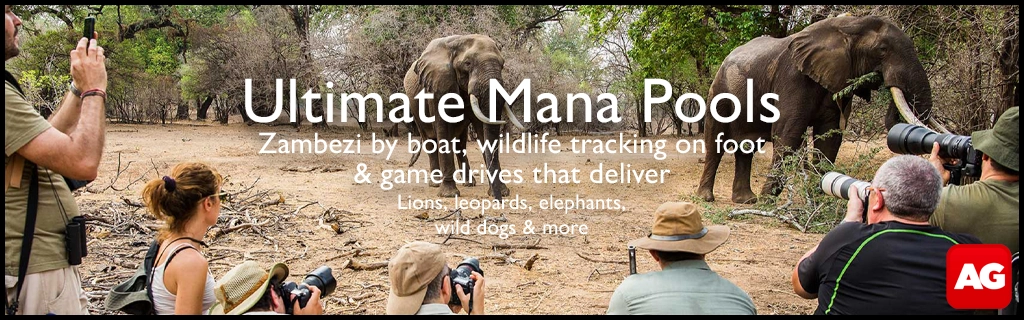

Want to support Africa’s protected areas? Visit Africa’s wilderness areas and support conservation through responsible tourism. We will help you to choose ethical lodges and in turn contribute to local economies helping keep ecosystems functioning and wildlife populations intact. Check out our safari ideas here, or let our travel experts plan a responsible and truly sustainable African safari for you

Want to support Africa’s protected areas? Visit Africa’s wilderness areas and support conservation through responsible tourism. We will help you to choose ethical lodges and in turn contribute to local economies helping keep ecosystems functioning and wildlife populations intact. Check out our safari ideas here, or let our travel experts plan a responsible and truly sustainable African safari for you

A study published in Nature has put a number to something conservationists have long suspected – Africa’s wildlife decline is not only a matter of losing species, but of losing ecological function.

Using an approach based on ecosystem energetics, the researchers found that energy flows through bird- and mammal-driven ecosystem functions across sub-Saharan Africa have declined by more than one-third. In practical terms, the continent has lost a substantial portion of the “ecological power” that animals once provided through feeding, movement, and ecological interactions.

The decline is uneven across land uses, and particularly severe outside of protected areas.

Measuring energy flow

Most large-scale biodiversity indicators track how many species remain, or how their populations have changed. But these measures can be blunt. They treat all species as equal, even though ecosystems do not work that way. A small insect-eating bird and an elephant may both count as “one species”, but they do not contribute equally to how ecosystems function.

To address this, the authors used energy flow as a common currency. Energy is captured by plants and then transferred up the food web as animals feed. The amount of food an animal consumes is a measurable proxy for its ecological influence – because consumption drives grazing pressure, predation, seed dispersal, nutrient cycling, and many other processes. In this study, energy flow was calculated as the annual food energy consumed by each species per unit area.

The dataset behind the results

The researchers analysed 1,088 mammal species and 1,955 bird species – nearly 3,000 species in total, representing 98% of Africa’s bird and mammal species (excluding seabirds). They modelled historical energy flows under conditions around 1700 CE, a time before major colonial and industrial land transformation had begun, and compared these with modern energy flows shaped by today’s land uses.

To do this, they analysed species range maps, population densities, body size and diet traits, metabolic equations estimating energy expenditure, and biodiversity intactness estimates describing how species abundances change under different land uses. They then grouped species by ecological role, identifying 23 functional groups (11 bird and 12 mammal functions), which were later aggregated into 10 major ecosystem functions.

These functions included grazing and browsing, insectivory (the ecological function of eating insects), seed dispersal, pollination, scavenging, nutrient dispersal, and carnivory (the consumption of animal tissue).

The key result: Africa’s ecological power has dropped sharply

Across sub-Saharan Africa, the total energy flow through wild birds and mammals has dropped to 64% of historical levels. That means roughly 36% of animal-driven ecological energy has been lost. This decline is not just a biological statistic. It indicates weakening ecological processes, because the animals that drive these processes are consuming less energy overall – either because their populations are smaller, they have disappeared from certain landscapes, or they have been replaced by smaller species with different ecological roles.

Land conversion has the strongest effect

The study found that energy flows fell dramatically in areas converted to intensive human land uses:

- Settlements: 27% of historical energy flow remaining

- Croplands: 41% remaining

- Unprotected untransformed lands (rangelands and near-natural lands): 67% remaining

- Strict protected areas: 88% remaining

Croplands and cities were responsible for 25% of the total decline in energy flows across the region. This result links land use change directly to ecosystem function. It suggests that agriculture and urban expansion are not only shrinking wildlife populations – they are reshaping how ecosystems operate.

Protected areas still retain most ecological function

One of the study’s strongest messages is that well-managed protected areas preserve ecological function far better than surrounding landscapes. Strict protected areas retained 88% of historical energy flows. This does not mean protected areas are unchanged, but it does mean that many animal-driven ecosystem functions remain close to intact when wildlife populations are maintained.

The collapse of megafauna functions

The steepest declines were seen in functional groups dominated by megafauna. Large herbivores – including grazers, browsers, and frugivores – historically accounted for more than one-quarter of mammalian energy consumption. Their energy flows have decreased by 72%.

The paper highlights that energy flows through megafauna-dominated functions such as nutrient dispersal, grazing and browsing, and apex carnivory are only 26–32% intact across the region. These are not minor ecosystem roles. Megafauna shape vegetation structure directly through feeding and nutrient release, and indirectly through predator–prey regulation.

Because 80% of Africa is classified as unprotected untransformed land, the wildlife decline, particularly of large herbivores and carnivores, may be altering vegetation patterns at a continental scale.

Small animals are becoming more dominant

While megafauna functions collapse, the study shows that African ecosystems are increasingly dominated by smaller species. The proportion of energy consumed by small birds and mammals increased from 69% historically to 78% today. Meanwhile, megafauna (>65 kg) fell from 16% of total energy flow to just 7%.

Passerine birds, including many of Africa’s songbirds, accounted for 8% of historical energy consumption but only 2% of total biomass, indicating that small species play outsized ecological roles. But small animals cannot fully replace the ecological roles of large animals. The authors note that smaller species do not compensate for attributes such as “large seed dispersal and greater daily transport ranges” that are unique to larger wildlife.

In other words, ecosystems may retain activity, but lose key ecological functions that depend on body size and movement across landscapes.

Key functions are disappearing outside protected areas

Some ecosystem functions show particularly steep declines.

Seed dispersal and pollination are highlighted as important examples. Seed dispersal is critical because many plants rely on animals to transport seeds away from parent trees, allowing forests and woodlands to regenerate and maintain diversity. Pollination is equally essential for reproduction in many plant species.

The study found that energy flows through seed dispersers are only 58% intact in untransformed lands, and 14% intact in croplands.

Pollination energy flows were 63% intact in untransformed lands and 25% intact in croplands.

These declines suggest that even where vegetation remains, the animal-driven processes that support plant reproduction and recovery may be severely weakened by wildlife declines.

Changes in how biodiversity loss is measured

The researchers argue that traditional measures of biodiversity intactness may overlook substantial functional losses because they treat all species as equally important.

Energy-based analysis changes the picture by showing which species and functional groups carry the most ecological weight.

This approach revealed that biodiversity intactness indices “substantially overestimate the intactness of the megafauna-performed functions”.

In other words, ecosystems may still appear moderately “intact” by standard biodiversity measures, even while critical large-animal functions have collapsed.

The bottom line

This study quantifies a continent-wide erosion of ecosystem function by tracking energy flows through nearly 3,000 bird and mammal species across sub-Saharan Africa. Its most important conclusion is stark: the ecological power of Africa’s wildlife has declined by more than one-third. In croplands and settlements, that decline is catastrophic. In protected areas, most ecological function still survives.

The findings reinforce a key conservation message: protecting wildlife is not only about saving species. It is about maintaining the living processes that allow ecosystems to function – processes that are already weakening across much of Africa.

Reference

Loft, T., Oliveras Menor, I., Stevens, N. et al. Energy flows reveal declining ecosystem functions by animals across Africa. Nature 649, 104–112 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09660-1

Further reading

Safaris can be sustainable! We dig into why conservation is an important consideration when planning your African safari

Ebony and ivory: a tale of two collapses – New research reveals how Africa’s forest elephants sustain its darkest wood – and what happens when they vanish

Africa’s lions are disappearing. New research shows that lion populations across the continent have declined by 75% in just five decades. Read more here

A study on population growth, resource exploitation & climate change highlights the necessary steps for preventing loss of wild habitats & species in Africa. Read more on how Africa’s wildlife needs to be safeguarded into the 22nd century

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()