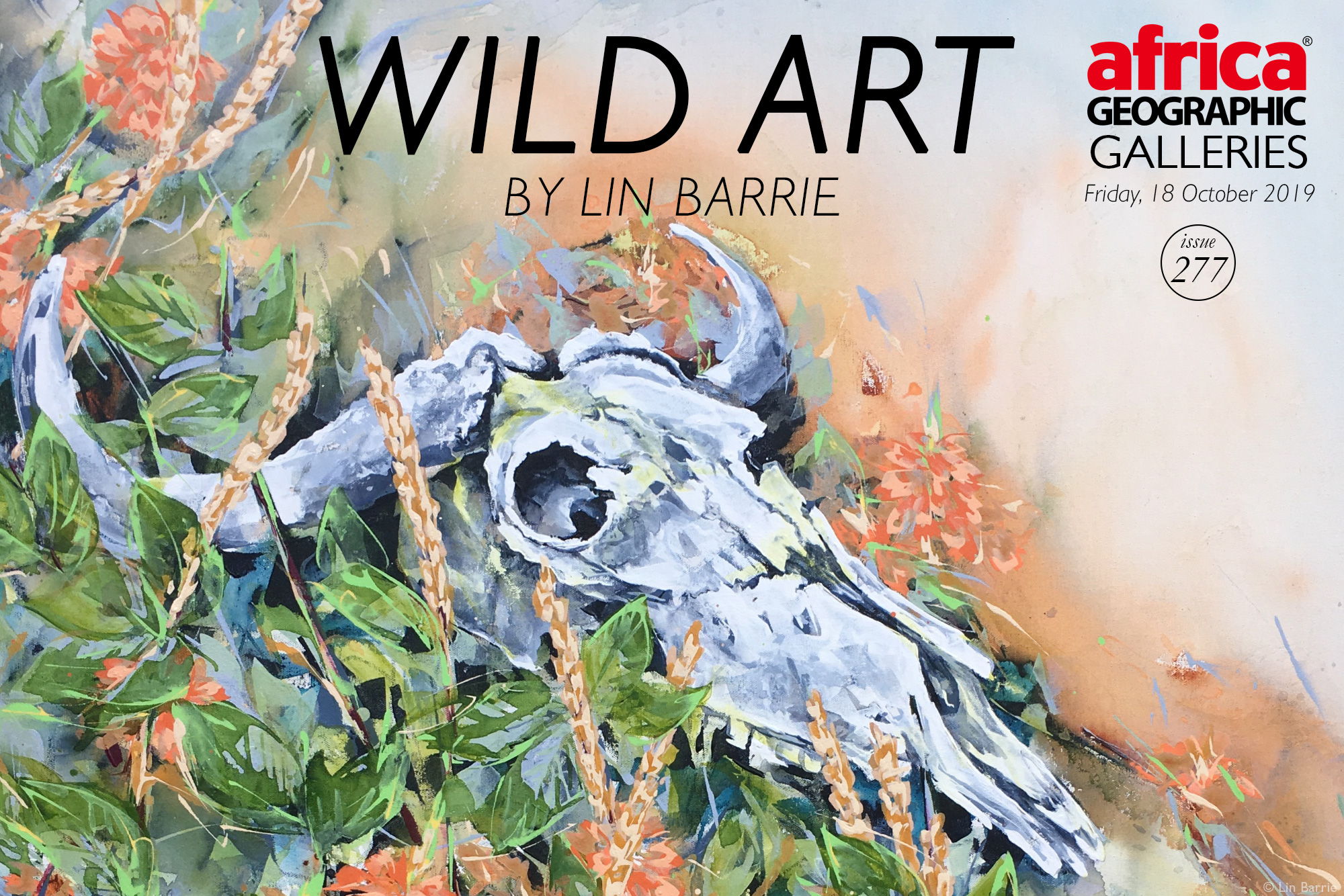

Of flowers and skulls,

life and death

Flowers and plants captivate me, skulls, skins and bones fascinate me. To me, they are potent symbols of life and death, inseparable and complementary. Living with my life partner Clive Stockil in the Lowveld wilderness of Zimbabwe, I am an artist and a naturalist, celebrating the indigenous plants and wildlife in the wilderness and in my gardens, and finding inspiration in the skulls, shells, stones and bones that nestle amongst the flowers, trees and leaves.

The following are a selection of some of my favourite pieces of art, and the inspiration behind them.

Of Giant Snails and Tradition, Fire and Totems

Shells are endlessly fascinating. The remains of giant African land snails, creatures of myth and story, are pristine white shells which they leave behind after they die. I have painted them tucked into the stems of the towering Strelitzia nicolae in my bush garden.

In the oral history of the Changana Chauke clan, who live adjacent to Gonarezhou National Park in the village of Chief Mahenye, there is a fascinating story told by the elders of how the giant African land snail came to be their totem. Back in those far-off days of hunter-gatherer existence, their rivals, the Hlungwani clan, had the knowledge and use of fire. The Chauke clan did not. Fire was supposed to be their totem, and yet they were deprived of it. By luck, a Chauke clan member surreptitiously managed to collect some fire embers from the rival clan by using an empty giant snail shell as a receptacle for the glowing treasure.

![]()

Caption: Photos and paintings of giant African land snails and strelitzias. All photos © Lin Barrie

The Chauke clan celebrated the fact that they, at last, had fire in their clan. They could now keep warm and cook their meat, and most importantly, they could fire and harden the full-bellied clay pots that the women crafted to carry life-giving water, cook food and brew sorghum beer. So they revered the giant snail – a creature which ‘withstood’ the fire; a creature which, even after an intense bush fire has passed, will eventually creep out of its underground hiding place unscathed.

Flowers and skulls

I am fascinated by the shapes and stories that lie in skulls and bones, and by the natural cycles of life and death. In being born, we are already in the process of dying, and so in my garden and my art studio I sketch, muse and paint endless combinations of bones, skulls and flowers.

Caption: Baboon skull and shells collage (left); and a collage featuring sketch, painting and photo of a wildebeest skull surrounded by flowers (right). Both images © Lin Barrie

Crossandras are summer flowering perennials in the Gonarezhou National Park and the Save Valley Conservancy where I live, tucked under the protective shade of mopani trees and blanketed with a profusion of delicate peach flowers during the rainy season.

Sabi stars are hardy survivors, succulents nestled in rocky places, their water-swollen, grey-skinned stems bursting forth with deep pink stars in the middle of our dry, dusty winters. Also referred to as an impala lily in South Africa and a desert rose in East Africa, these flowers seem to me to be the epitome of hope, bursting forth in wild colour and exquisite form from a leafless grey stem.

Fallen kigelia (or sausage tree) flowers – gorgeous wine red cups of goodness – are sought after in the winter months by impala, as they forage beneath the trees of our riverine woodlands. And in turn, the impala is hunted by the slinky leopards who lie in ambush, dappled coats merging into the surrounding nature.

Caption: A collage of kigelia flowers, leopard print and impala skull (left); Kigelia flowers and leaves (right). Both photos © Lin Barrie

An old warthog skull that I found years ago in the bush near my house, a victim of leopard or lion, and with shapes as wondrous and strange as any dragon or dinosaur skull could be, has pride of place in my studio when I am in sketching mood. A treasured palette knife that belonged to my father is my favourite tool, and acrylics are my preferred medium when working in the field, due to their fast drying time. The palette knife is perfect for capturing the curve of a tusk.

Caption: Warthog skull (left); and up-close of palette knife while painting the tusk of the warthog skull (right). Both photos © Lin Barrie

The porcupine that visits regularly to nibble on the vegetation around our bush house thrills me with his magnificent quills – and also loves to inspect the bowl of dog food while our Jack Russells keep a respectful distance!

Amongst my treasures, I have a special skull, a painted wolf (African wild dog) alpha female. I once watched her at her den with five-week-old pups; she died when a lion bit through her spine. The rest of the pack rallied and fed the eight pups, successfully rearing the tiny mites to adulthood. That was a natural death, the result of inter-predator confrontation and as such, a sad but acceptable reality.

Caption: Porcupine and quills collage (left); and alpha female painted wolf (African wild dog) skull (right). Both photos © Lin Barrie

Snares and death

The unacceptable reverse is true of indiscriminate animal deaths by wire snares, pesticides, poisoning or other human activity such as illegal wildlife trade.

Just like how wild predators utilise their prey, we humans utilise animal parts. We wear leather shoes and belts; many of us eat animal products; we use skins and horns in musical instruments, whether ivory for piano keys or skins and kudu horns for traditional dancers. Our challenge is, how do we utilise the world around us ethically, sustainably?

Traditional hunter-gatherers would have created snares from woven grass to trap the bushmeat that they needed to feed their families, and, if not recovered, these woven snares would have broken down over a short time, becoming harmless. The advent of iron gin traps and the availability of deadly indestructible wire from fences and telephone cables have created monsters (‘Land Mines’ I call them), which lurk in the environment, in the leaves and undergrowth, and remain deadly for years and years to come.

Painted wolves are particularly susceptible to running through fence wire and copper wire traps set for antelope in the bush. Constantly we face the issue of losing these elegant, endangered creatures if we cannot intervene in time to remove the constricting wire from their necks or waists.

Painted wolves are crepuscular, usually hunting in the hours of dawn and dusk. Still, on many full moon nights around the campfire or at our bush house I have heard these hunters calling their evocative “hoooo” call to each other, having enough light by the glowing moon to hunt late into the night. And I sit there worrying, knowing that then they are even more vulnerable to running through unseen snare lines.

Caption: A selection of collages showing the various gin and wire traps. All photos © Lin Barrie

Over the years I have sketched many skulls from animals lost to snares and poaching: a rhino skull from a female who died of bullet wounds near our bush house recently, after running wildly through the mopane trees from the poachers who shot at her; the pelvis and bones from a male black rhino who was shot by poachers, then ran away and died below our bush house a few years ago.

Caption Left and Top right: Details of the two parts that make up the piece ‘Winter Woodland and Rhino Skull’, diptych, acrylic on stretched canvas, each panel 2 x 3 feet; Bottom right: Lion’s mane grass and mopane trees in winter, photographed on my daily commute to the painted wolf den near my bush house. The russet-red leaves nestle in the hardened footprints made by elephants in the previous wet season. All photos © Lin Barrie

How do we maintain balance and honour the natural cycles of birth and death? How do we address illegal trade and excess harvesting of our wildlife and plants? How do human communities live with their environments so that both benefit from the relationship? What legacy do we leave our children?

Are we living in the Garden of Eden, or are we well on our way to Armageddon?

Caption: Mozambique Changana dancers and Zimbabwean drums with kudu horn (left); ‘Zebra, Coat of Many Colours’, acrylic and oil bar on canvas, 180 x 230 cm (right). Both photos © Lin Barrie

My large mixed media painting on canvas, called ‘Zebra, Coat of Many Colours’, reflects joy, a belief that varied solutions of many hues can be embraced to maintain ecosystems for the good of people and wildlife. To embrace our Garden of Eden before it is too late.![]()

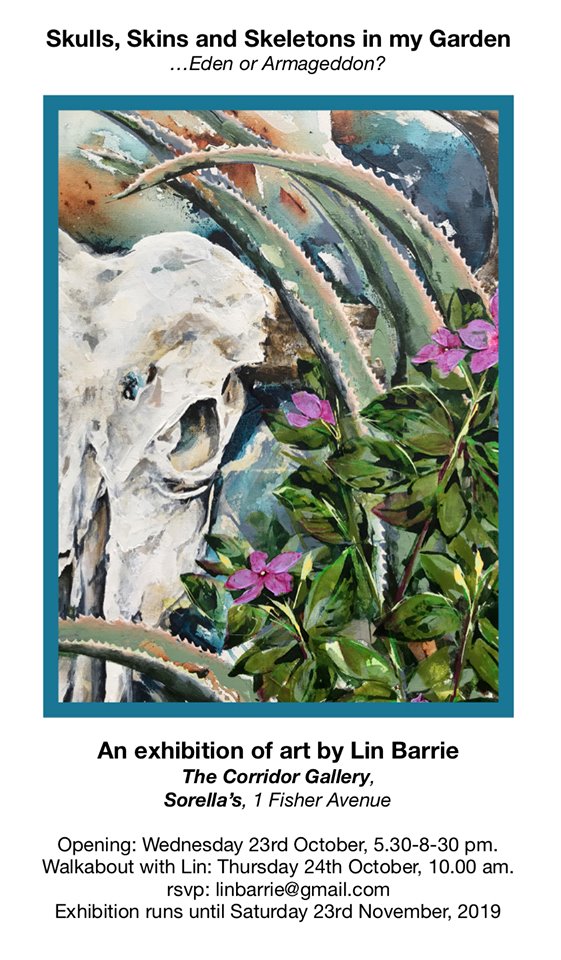

EXHIBITION

“Skulls, Skins and Skeletons in my Garden… Eden or Armageddon?” is the title of my solo art exhibition at The Corridor Gallery in Harare, Zimbabwe, which will open on 23rd October 2019, and will run for a month after that.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, LIN BARRIE

Expressing herself with found objects, palette knife and paintbrush, Lin Barrie believes that the abstract essence of a landscape, person or animal can only truly be captured by direct observation. She immerses herself in her subjects, whether observing African night skies, sketching rhinos drinking at a favourite waterhole, watching African wild dogs and their pups, or capturing the mood of an abstract landscape or traditional dance. She is fascinated by the synergies between elements of landscape, people and animals, such as the flow of water which becomes fish, the texture of baobab skin which so closely resembles that of elephants’ limbs, the shapes of monumental rock outcrops which take human or animal forms, plants which echo human parts, animal totems and people. You can see more of her artwork on her website and Facebook page.

Expressing herself with found objects, palette knife and paintbrush, Lin Barrie believes that the abstract essence of a landscape, person or animal can only truly be captured by direct observation. She immerses herself in her subjects, whether observing African night skies, sketching rhinos drinking at a favourite waterhole, watching African wild dogs and their pups, or capturing the mood of an abstract landscape or traditional dance. She is fascinated by the synergies between elements of landscape, people and animals, such as the flow of water which becomes fish, the texture of baobab skin which so closely resembles that of elephants’ limbs, the shapes of monumental rock outcrops which take human or animal forms, plants which echo human parts, animal totems and people. You can see more of her artwork on her website and Facebook page.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()