Shades of ochre

Scattered along the regions of Western Namibia, half-buried ghost towns are being reclaimed by the sand. Quite aside from providing the perfect setting for reflective social media posts by a travelling influencer, these towns are a testament to the immutable powers of desert and ocean. In a land of extremes, the daily battle for survival plays out against the backdrop of stunning scenery.

Western Namibia and the Namib Desert

Namibia has one of the highest percentages of protected land in Africa, with approximately 40% of the country under state, private, or community protection. Much of this is found along the country’s western edge, bordering the savage Atlantic Ocean coastline. Here, desert meets sea, where ocean winds and thick sea fogs have shaped a rippling vista of sinuous dunes sheltering some of the most superbly adapted life on the planet.

The Namib Desert (from which Namibia takes its name) is one of the world’s oldest deserts – some 55-80 million years. The word “Namib” originates in the Khoekhoe language and literally means “vast place”. The desert stretches in a narrow strip along Namibia’s coast, from the Olifants River in South Africa to the Coporala-Carunjamba catchment in Angola. There are sections where the average annual rainfall is just two mm. Despite the exceptional aridity, scientists believe that it is home to more endemic species than any other desert.

The Namib is also extremely rich in diamonds, which have played a significant role in the shaping of Namibia’s history. The Tsau ||Khaeb National Park (formerly Sperrgebiet) along the southern coastline remains entirely inaccessible to self-drive tourists, despite mining operations taking place in five per cent of the park. It was here that the Bom Jesus, a 500-year-old shipwreck, was found sheltering secrets of the historic ivory trade. Further north, however, is where the true Namibian jewels are to be found – otherworldly landscapes, magnificent scenery, desert-adapted wildlife and star-studded night skies devoid of light pollution.

Sossusvlei (and the Namib-Naukluft National Park)

Sossusvlei is perhaps Namibia’s most famous landmark and is undoubtedly one of the most photographed places in sub-Saharan Africa – for good reason. It is an endorheic drainage basin for the Tsauchab River, with “Sossusvlei” roughly translating as “no return” or “dead-end marsh”. The salt and clay pan is surrounded by spectacular dunes, coloured bright red and orange by oxidised iron. The Tsauchab River is ephemeral, and years of dry spells can pass before it flows, filling the pan with precious but short-lived water.

Sossusvlei is at the heart of the enormous Namib-Naukluft National Park, which is Namibia’s largest protected area at 50,000km2 (5 million hectares). However, so renowned is Sossusvlei that it is often used colloquially to refer to any of the surrounding landmarks and vleis. The rich, soft sand has blown in over the centuries to create some of the largest dunes in the world, their shape dynamic and ever-changing. The tallest of these in the national park is Dune 7, standing at 388m, while Big Daddy overlooks the Sossusvlei area from a height of 325m. Scampering up to the top of these dunes on sliding sands presents a view unlike any other, with the umber sands stretching as far as the eye can see.

Not far from Sossusvlei and flanked by Dune 45, Deadvlei is equally scenic. Here, the skeletons of trees fed by a river, now long redirected, bear witness to the harshness of the desert. The lack of moisture has prevented the trees’ natural decomposition, leaving them standing as eerie silhouettes against the pale white of the salt pan.

Staring in awe at the night sky is a human experience shared across continents, cultures and circumstances. From practical navigation to fanciful myths and legends, people are drawn to the infinite splendour of the Milky Way, studded with diamonds and the silvery glow of the gentle moon. Without so much as a hint of light pollution, stargazing in the Namib-Naukluft National Park is a positively humbling experience. NamibRand Nature Reserve, a private reserve adjacent to the park, is the only official International Dark Sky Association Reserve in Africa.

The Skeleton Coast

North of Swakopmund, the desert coastline continues as the aptly named Skeleton Coast, which encompasses the 16,000km2 (1.6 million hectares) Skeleton Coast National Park. The San people of Namibia’s interior are reputed to call it “the land god made in anger”, while Portuguese traders referred to the “gates of hell”. At the mercy of perfidious tides and cruel winds, the beaches are strewn with the debris of countless shipwrecks where everything from liners to gunboats has foundered over the centuries. No one knows for sure how many ships have been claimed by Namibia’s wicked coastlines – many buried quite literally by the shifting sands of time. However, the skeletal remains of luckless vessels are not alone, and bleached white whale bones bear testament to the leviathans’ struggles to navigate the waters. The net effect is an eldritch but astonishingly beautiful setting.

Sailors of old who survived their near-drowning would have found themselves stranded in an inhospitable setting, faced with the rolling dunes and rocky hills of the Namib Desert. It seems counterintuitive that anything could survive here, especially large mammals, but the Skeleton Coast is home to desert-adapted elephants, rhinos, and lions. Here, the long-limbed elephants cover up to 60km in a day, with ancestral survival skills passed from mother to offspring in an enduring repository of herd memory. The predators, too, have learnt to live on a knife-edge. Lions, jackals, and hyenas trawl the beaches for food. A rotting whale carcass is a rare boon, not to be passed up.

While the icy seas have made the land uninviting, the cold currents are rich in marine life, which in turn supports a massive colony of Cape fur seals at the Cape Cross Seal Reserve just north of Hentie’s Bay. Here, visitors can watch the bulls fight during the breeding season in November and December, timed to coincide with the emergence of the tiny, vulnerable seal pups. Though deeply endearing, a gathering of this many seals is a viscerally pungent experience capable of singeing the nose hairs and bringing tears to the eyes.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, the putrid stink does little to deter hungry predators. Resourceful jackals and brown hyenas are always lurking on the periphery, waiting to take advantage of an overly adventurous or lonely pup. Since their recovery in the park, the beach-combing lions have once again learnt to capitalise on marine resources, and up to 79% of their diet will consist of seals and seabirds. (For more on the fascinating lives of Namibia’s beach lions, see here.)

Huab River Valley (Damaraland) and Kaokoland

Bridging the gap between the Skeleton Coast to the west and Etosha National Park to the East, the Huab River Valley (Damaraland) and Kaokoland mark the transition from desert to arid savanna habitat. Equally dramatic and breathtaking as Sossusvlei, the scenery here is all hard lines and granite angles, moulded from rock rather than soft, shifting sands. There are no national parks – instead, the land is “unofficially” protected by a series of private and community conservancies. The entire region is a kind of open-air museum exhibiting everything from ancient geological wonders to early human history.

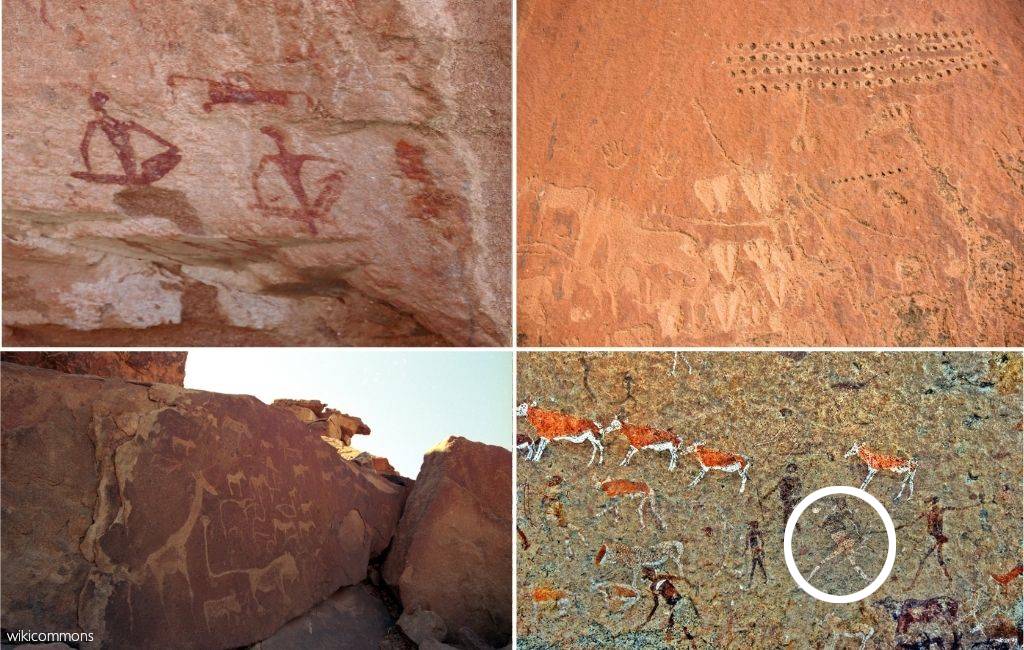

Hidden within the sun-burnished rock formations and mountains is one of the finest collections of prehistoric rock art in Southern Africa. The vast majority are found at the Twyfelfontein engravings, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There are approximately 2,500 etchings depicting people, wild animals (including a penguin and a seal, although the coast is 100km away), and cattle. The petroglyphs are believed to be between 2,000 and 6,000 years old and were probably instructional, teaching young hunters about their prey. Further south, the many caves and overhangs of Brandberg Mountain house more than 1,000 rock paintings. The most famous of these is the “White Lady”, now believed to depict a mystical, shaman-like figure.

Geological wonders of the area include the famous Spitzkoppe granite inselbergs and the Organ Pipes – a series of jagged, narrow rock formations formed when the supercontinent of Gondwana began to pull apart. Even older than the Organ Pipes, the Petrified Forest displays the remnants of a flood dating back more than 200 million years ago, when enormous trees were washed downstream as the ice age ended. The trees were covered in cloying mud and eventually fossilised. Research indicates that they belonged to the ancestral family of European firs and spruces.

Although perhaps not in the same numbers as those depicted in their rock art, wildlife still flourishes in this section of north-central Namibia. Many of the concessions and conservancies are contiguous with the Skeleton Coast National Park. The desert-adapted elephants and lions are always highlights, but visitors can also spend time on foot tracking the critically endangered black rhinos that inhabit the area.

Life on the edge

Consistent across western Namibia is nature’s remarkable capacity to adapt to extreme conditions. This applies to everything from plants to elephants. For smaller plants and animals, it is often the thick ocean fog (so cursed by sailors) that is key to their survival. The primitive welwitschia, with its gnarled and unassuming appearance, can survive for hundreds of years on mist and dew alone. The marvellous little lithops are equally fantastical. These plants are living stones – clever succulents perfectly designed to blend into the pebbles. Their fenestrated leaves and transparent epidermal windows enable the plant to photosynthesise without water loss.

At a more mobile level, Namibia is home to a beetle family that has inspired several water-saving biomimetic designs. A series of specialised bumps, ridges, and grooves on Namib desert beetles’ exoskeletons help harvest the fog and direct dribbles of water to their mouths.

Travel, marvel, explore

As unwelcoming as the landscape may seem, travelling in Namibia is so safe and easy that it is sometimes referred to as “Africa for beginners”. A self-drive adventure is relatively straightforward, and although some of the dirt roads are bumpy and corrugated, the slow progress offers a chance to explore the country’s charms. When travelling from delightful, isolated farmhouse accommodation to quaint souvenir shops, the boundless scenery offers ample opportunities to take romantic, appropriately filtered Instagram shots or photos for canvas masterpieces. Although accommodation options tend to be quite expensive outside the main cities, low-budget campsites are readily available. In a country with the second-lowest population density in the world, a journey through Namibia can feel like stepping back in time.

Want to go on safari to Western Namibia? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

Close to the main city of Walvis Bay and the town of Swakopmund, the daredevil traveller will find more adrenaline-inducing activities like sandboarding down the dunes. However, the real magic of western Namibia lies in the ability to lose oneself in the exquisite surroundings and bask under a blanket of silence and in the sense of pure isolation. In today’s fast-paced world, it is the perfect way to return to a more human schedule.![]()

For further reading, see:

Namibia: Spectacular colours of a magnificent wilderness destination

Best photographic hotspots in Namibia

Best photographic hotspots in northern Namibia

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()