AFRICA'S UNSUNG GARBAGE COLLECTION HEROES

“When one thinks about vultures, one envisions a bald-headed, blood-thirsty scavenger waiting for something or someone to perish. We have been brought up to believe that evil surrounds vultures, and this has led to cinematography portraying the species in a negative and unloved light. This has most certainly contributed to the species being disliked and misunderstood by so many of us.

Twenty years ago, I had no appreciation for vultures. I did not care for them much, let alone understand them, and I most certainly had no inkling that I would be dedicating my life to saving such an underappreciated and misjudged species. They are our natural garbage collectors, and we owe them our gratitude for keeping our environment balanced.” ~ Kerri Wolter (Founder/CEO of VulPro)

CLASSIFICATION

Vultures are classified into two groups – the Old World and the New World. New World vultures are found in North and South America and are represented by seven species belonging to five genera. Old World vultures are found throughout the continents of Africa, Asia and Europe and are represented by 16 species belonging to nine genera. However, the two groups are not genetically closely related, but instead, their similarities are due to convergent evolution (when species have different ancestral origins but have developed similar features).

Old World vultures belong to the family Accipitridae, which also includes the eagles, buzzards, kites and hawks. New World vultures belong to the family Cathartidae, that includes condors.

A significant difference between the two groups is that Old World vultures do not have a good sense of smell and thus locate their meals by sight, whereas New World vultures have a keen sense of smell and sharp eyesight.

For this story, we will be looking at various species of Old World vultures.

MORE ABOUT VULTURES

Both Old World and New World vultures are scavenging birds, feeding mostly from carcasses of dead animals. However, some have broad food habits, and in addition to carrion will also consume garbage and even excrement. Vultures seldom attack a healthy living animal but may kill the wounded or sick.

A particular characteristic of many vulture species is a bald head, devoid of feathers. Most researchers suggest that this is because it would be difficult to maintain a feathered head and keep it clean from all the blood and other fluids picked up while feeding on carcasses. However, recent research theorises that a bald head can also help with thermoregulation.

Vultures are opportunistic feeders and when prey is abundant will gorge themselves until their crop is full, after which they will sit in a half torpid state to digest their food. Most species have powerful hooked beaks that are used to tear hide, muscle and bone from carcasses.

When vultures of different species descend on a carcass, it may look like a ‘first come first served’ frenzied mess, but there is a strict hierarchical feeding structure based on body size and strength of beak. Vultures with powerful beaks, such as the dominant lappet-faced vultures, are the first to the carcass, tearing it open to allow other vultures to feed, such as white-backed vultures and white-headed vultures who will gorge on the soft tissue of the carcass. Smaller vultures will usually wait for the scraps left behind by the larger, more dominant species.

All vultures have very long, broad wings that allow them to soar gracefully at great heights, catching the thermals and remaining aloft for hours with minimal effort. With their keen eyesight, they can scan for carrion or spot other vultures descending to prey from miles away.

When it comes to nesting, Old World vultures build large platform nests made out of sticks – in trees or on cliffs. They may use the same nest for several years, taking turns sitting while their partner finds food. The majority of Old World vultures incubate a single egg at a time. Vultures generally do not have strong feet or legs, so they are unable to carry food back to their young. Instead, they gorge themselves on food, filling up their crop, and upon returning to the nest regurgitate the food for the young to eat.

All vultures play an essential ecological role in the ecosystem by disposing of dead carcasses and decreasing the spread of diseases from animal remains that would otherwise rot. Unfortunately, the majority of species are facing a continual and rapid decline in numbers due to a variety of threats, which is not good news for the future state of the ecosystem.

THREATS

Today, vultures face an unprecedented onslaught from human activities, and the IUCN Red List currently lists many of the Old World vultures as ‘Vulnerable’, ‘Endangered’ or ‘Critically Endangered’. Threats range from electrocutions and collisions with electrical structures to poisonings and exposure to toxicity through veterinary drugs. In Africa, the majority of deaths are attributed to poisonings and the harvesting of body parts for the bushmeat trade and use in traditional medicine – it is believed that the heads, or brains, of vultures, provide powers of premonition or foresight.

Because vultures tend to circle over potential prey, ivory or rhino horn poachers lace the carcasses with poison intending to kill the vultures so that they won’t alert the authorities to future kills. Vultures are also unintentionally killed by pest control poisons when consuming the carcasses of predators that have been poisoned by farmers who want to protect their livestock.

ENDANGERED SPECIES HEADING TOWARDS EXTINCTION

Africa is home to 11 Old World vulture species, of which six are confined to the continent while the rest also occur elsewhere in Eurasia. Seven of the African vultures are on the verge of extinction, and we cover these species below, based on information provided by the IUCN Red List and VulPro.

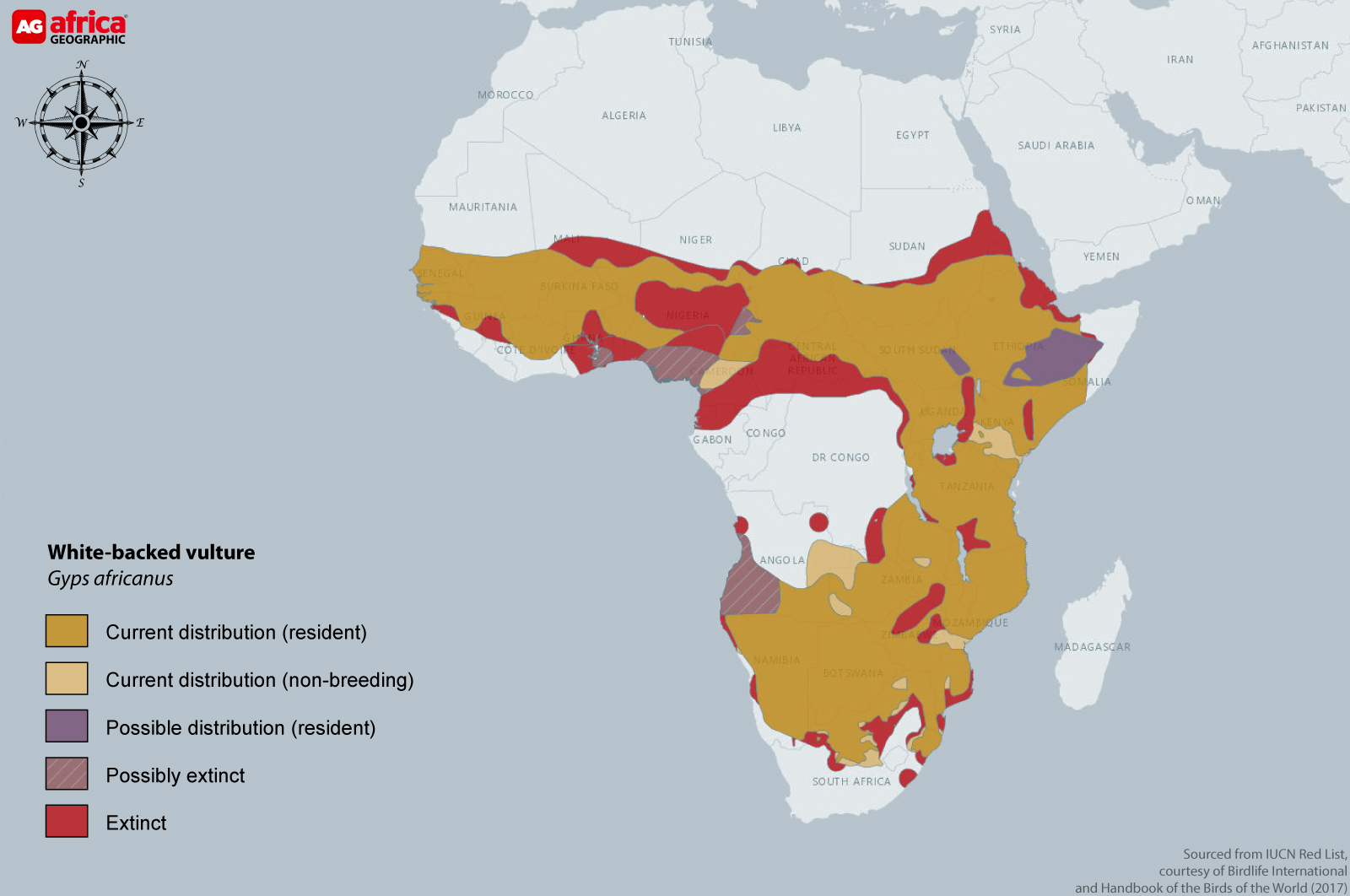

WHITE-BACKED VULTURE – CRITICALLY ENDANGERED

The white-backed vulture (Gyps africanus) is endemic to Africa, being the most widespread and common vulture on the continent. It is ‘Critically Endangered’ owing to the very rapid decline in habitat loss, degradation, and prey, and also due to hunting for trade, persecution, collisions and poisoning. The IUCN Red List states that its global population is estimated at 270,000 individuals, while South Africa has an estimated 40,000 individuals left.

They feed in large numbers at a carcass, resulting in lots of hissing and grunting to protect their share of the food. They clean and preen themselves thoroughly after feeding and are often seen bathing and sunbathing together with other vulture species.

HABITAT AND REPRODUCTION

It is a lowland species which prefers wooded savannah, particularly acacia trees. They require tall trees for nesting and have been recorded nesting on electricity pylons in South Africa. They nest in loose colonies of 2-13 birds. Nests are made out of sticks and lined with grass and leaves. They breed at the start of the dry season, and the female lays a single egg, sharing the incubation with her mate for around 56 days. Both parents feed the pale grey chick until fledging at 120-130 days of age.

DISTRIBUTION

The white-backed vulture occurs from Senegal, Gambia and Mali in the west, throughout the Sahel region to Ethiopia and Somalia in the east, through East Africa into Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia and South Africa in the south. They are now extinct as a breeding species in Nigeria, with only one stronghold in Ghana.

APPEARANCE

White-backed vultures have bald heads and long necks. The adults are brown to cream-coloured with dark tail and flight feathers. They have a white rump patch and ruff. Juveniles are generally darker in colour.

• Body length: 89-98 cm

• Wingspan: 210-220 cm

• Weight: 4.2-7.2 kg

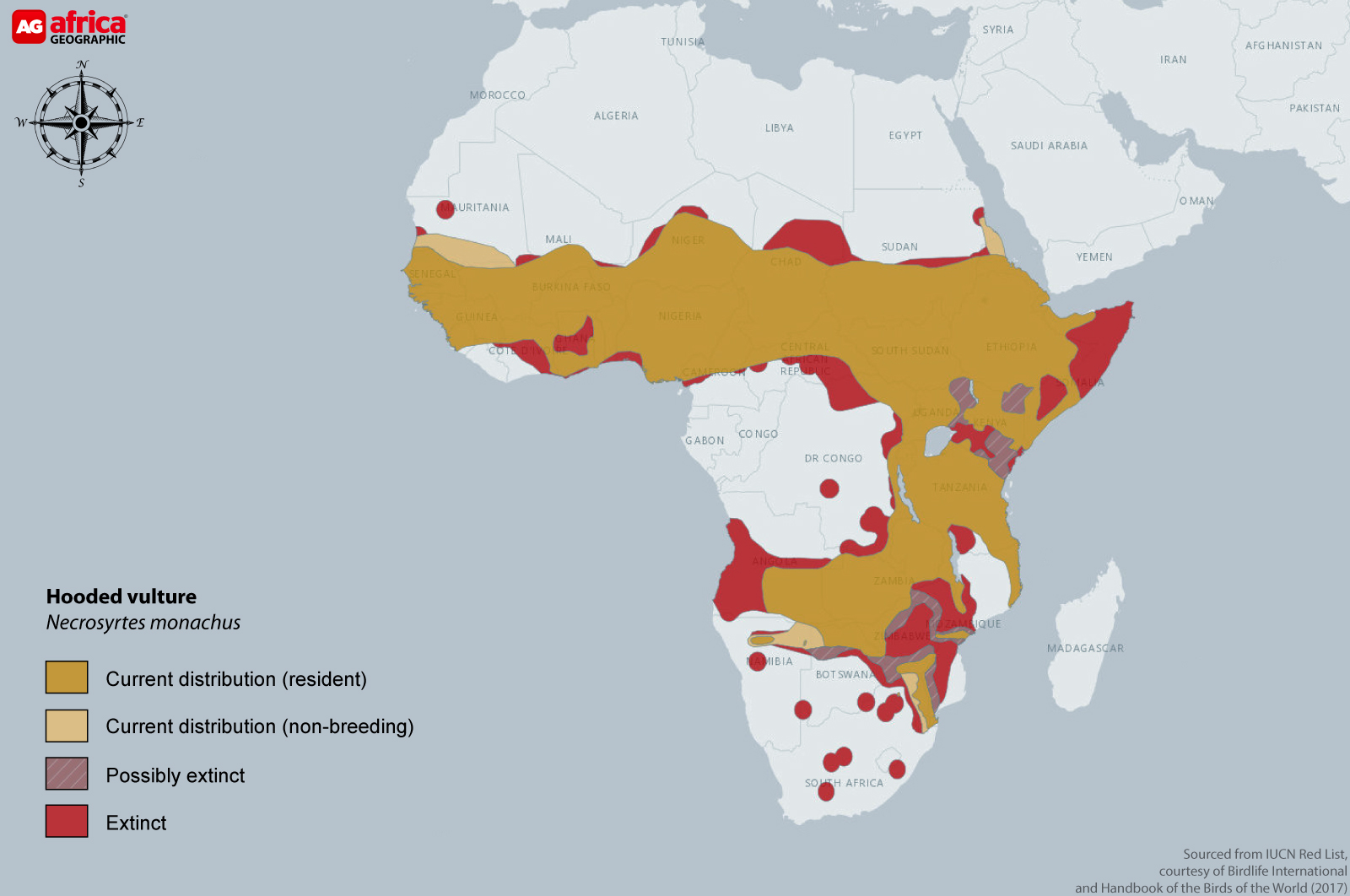

HOODED VULTURE – CRITICALLY ENDANGERED

The hooded vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus) is endemic to southern Africa. It is listed as ‘Critically Endangered’, and populations are declining rapidly due to indiscriminate poisoning, trade for traditional medicine, hunting, persecution and electrocution, as well as habitat loss and degradation. The IUCN Red List states that its global population is estimated at a maximum of 197,000 individuals.

Hooded vultures feed on insects and carrion and are known to follow ploughs to eat exposed larvae and insects, as well as making use of rubbish dumps for carrion. The adults are very quiet and seldom vocalise.

HABITAT AND REPRODUCTION

Hooded vultures are often associated with human settlements, but are also found in open grassland, forest edge, wooded savannah, desert and along coasts. Very little is known about their breeding habits, although it has been noted that baobabs are usually their go-to roosting and nesting trees. In West Africa and Kenya, it breeds throughout the year, but especially from November to July. Breeding in northeast Africa occurs mainly in October-June, with birds in southern Africa tending to breed in May-December. A clutch of one egg is laid with an incubation that lasts 46-54 days, followed by a fledging period of 80-130 days.

DISTRIBUTION

This species is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa; from Senegal and southern Mauritania east through southern Niger and Chad to southern Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia and western Somalia, southwards to northern Namibia and Botswana, and through Zimbabwe to southern Mozambique and northeastern South Africa.

APPEARANCE

Hooded vultures are smaller and shyer than other vultures, with the female being larger than the male. It is a small, scruffy-looking vulture with mostly brown wings with a pinkish bald head and beige hood. Juveniles usually have a pale blue face and a hood of short, dark brown down feathers rather than beige.

• Body length: 67-70 cm

• Wingspan: 160 cm

• Weight: 2 kg

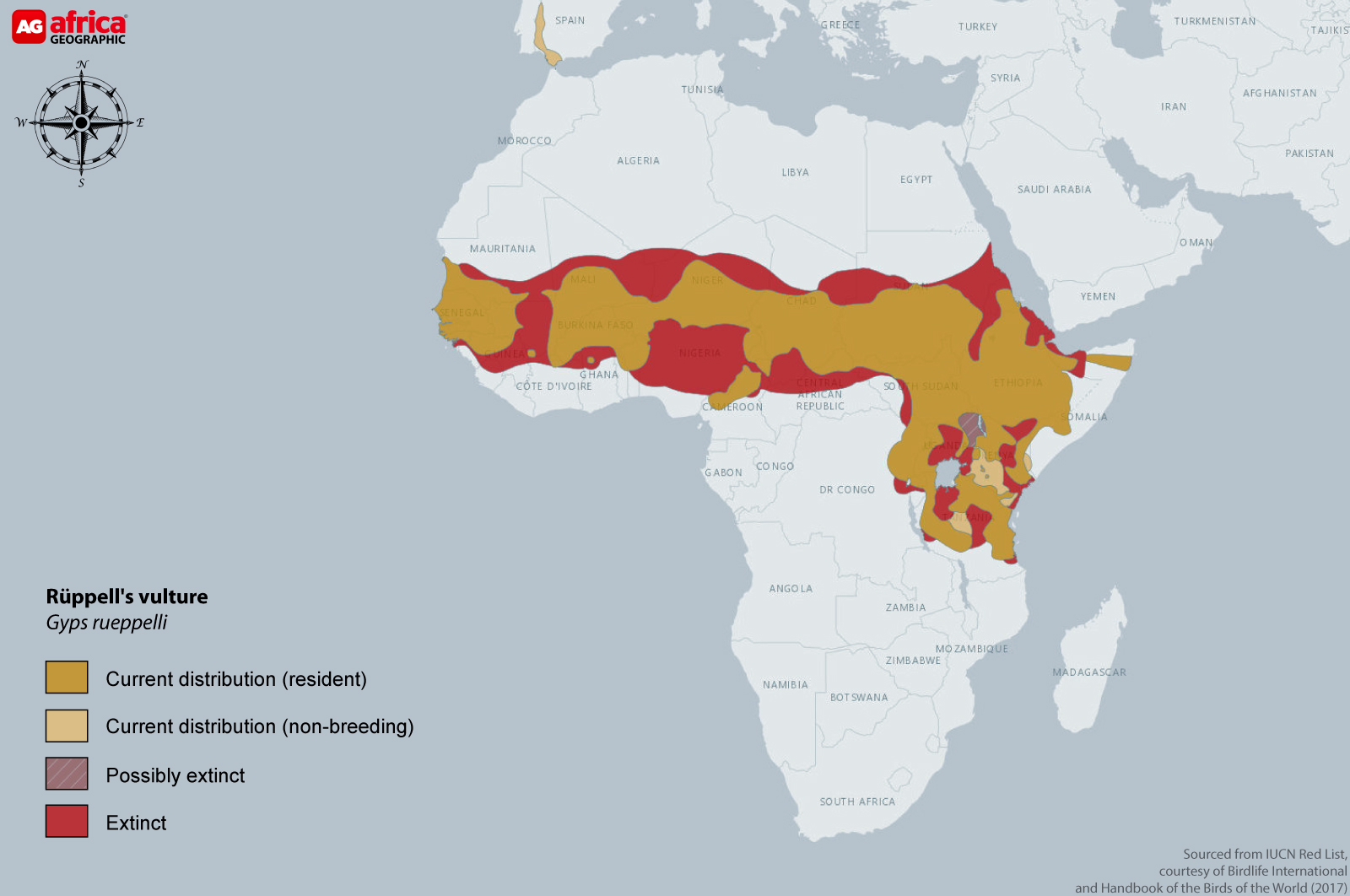

Rüppell’s vulture – CRITICALLY ENDANGERED

The Rüppell’s vulture (Gyps ruppellii) was uplisted in 2014 from ‘Endangered’ to ‘Critically Endangered’ due to severe declines in parts of its range. As with all threatened vultures, the population is undergoing a very rapid decline due to habitat loss, degradation, declines in prey (wild ungulates), hunting for trade, collision and poisoning. The IUCN Red List states that its current population is estimated at 22,000 mature individuals.

This vulture is regarded as the highest flying bird in the world and is known to fly as high as 37,100 feet (11,278 metres) above sea level.

HABITAT AND REPRODUCTION

Found in open areas of acacia woodland, grasslands and montane regions, these vultures breed in colonies of up to 2,200 birds, building large nests on cliff faces. They lay only one egg per year, and both parents incubate the egg for a period of up to 55 days, with young becoming independent during the following breeding season.

DISTRIBUTION

Rüppell’s vultures occur throughout the Sahel region of Africa – Senegal, Gambia and Mali in the west to Sudan and Ethiopia in the east– as well as savannah regions in the east of Africa to Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique. Since the 1990s there has been a series of records involving small numbers of individuals in Spain and Portugal.

APPEARANCE

Rüppell’s vultures are a medium-sized vulture. The adults have mottled dark-brown/black plumage with pale creamy edging to the body feathers. The flight feathers are dark, and they have a white ruff, dark neck and pale head. Juveniles have a dark beak and paler body plumage.

• Body length: 84-97 cm

• Wingspan: 260 cm

• Weight: 7-9 kg

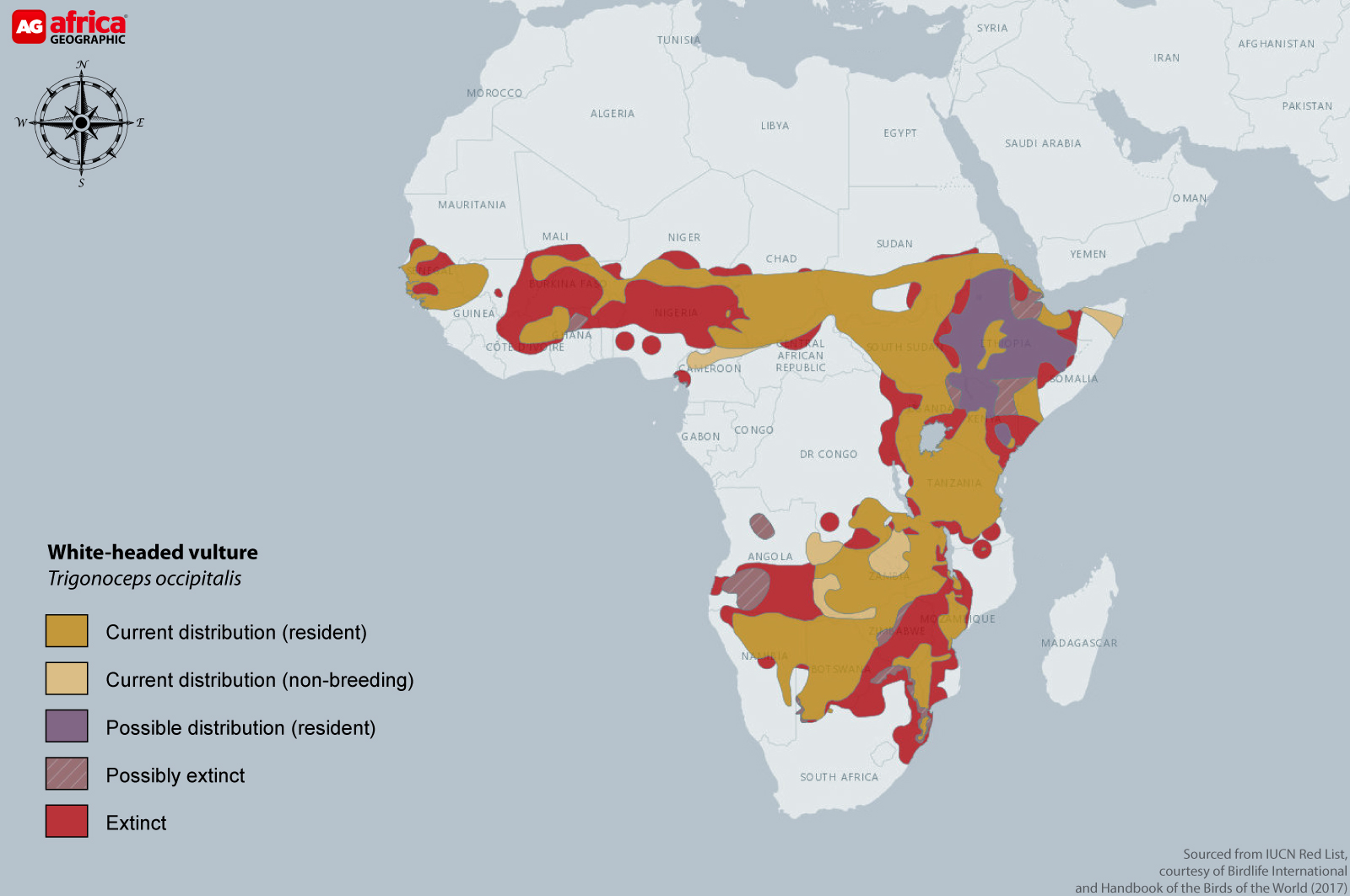

WHITE-HEADED VULTURE – CRITICALLY ENDANGERED

The white-headed vulture (Trigonoceps occipitalis) is endemic throughout sub-Saharan Africa and is listed as ‘Critically Endangered’ due to poisoning, persecution and ecosystem alterations. The IUCN Red List estimates a population of 5,500 individuals, with severe declines throughout its West African range. Poisoning seems to be the major factor in the decline of this species.

This shy species tends to avoid human habitation. They fly lower than other vultures are often the first vulture species to arrive at carcasses, where they keep their distance from vulture gatherings, waiting for larger species such as lappet-faced vultures to move off. They are quite agile on the ground and fight by leaping into the air and lashing out with their strong talons.

HABITAT AND REPRODUCTION

White-headed vultures prefer mixed, dry woodland at low altitudes, avoiding semi-arid thorn belt areas. The top of tall trees is where they will roost and nest, with nests being built mostly in acacia tree species and baobabs. Usually, one egg is laid during the dry season. Incubation lasts about 43-54 days and is shared by both parents. The young fledge at about 115 days and is fed by parents for up to another six months.

DISTRIBUTION

With an extensive range in sub-Saharan Africa, their distribution is from Senegal, Gambia and Guinea-Bissau east to Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, and south to easternmost South Africa and Swaziland.

APPEARANCE

This stocky, medium-sized bird has predominantly black and white plumage. They have a pinkish-orange hooked beak with a white crest and a downy white head. The skin is bare around the eyes, cheeks and front of the neck. They have white legs and belly with a black breast and ruff. Flight feathers and tail are black. Juveniles are dark brown with a white head and brownish top of the head, and white mottling on the mantle.

• Body length: 78-85 cm

• Wingspan: 207-230 cm

• Weight: 3.3-5.3 kg

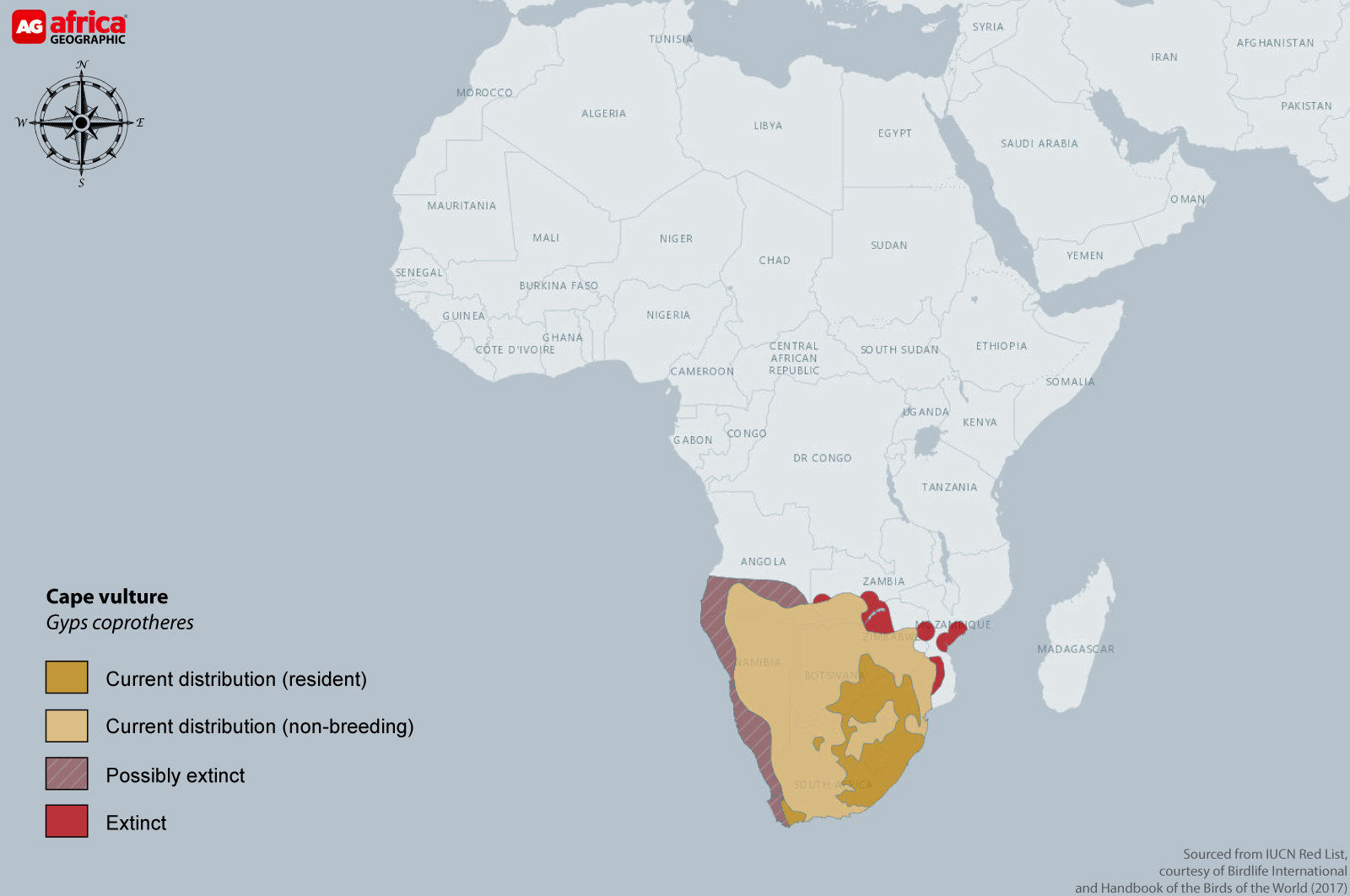

CAPE VULTURE – ENDANGERED

The Cape vulture, or Cape griffon vulture (Gyps coprotheres) is endemic to southern Africa and is found mainly in South Africa, Lesotho and Botswana. The IUCN Red List categorises this species as ‘Endangered’ as its population is declining rapidly. However, recent increases in parts of its South African range mean declines are not thought to be sufficiently strong to warrant listing as ‘Critically Endangered’. The main threats these vultures face are poisoning, electrocution on pylons or collision with cables, loss of foraging habitat and unsustainable harvesting for traditional uses. Global population numbers are at approximately 9,400 mature individuals or 4,700 breeding pairs.

Cape vultures always make quite the scene at large carcasses and descend in large numbers, arguing over food with harsh, grating calls or standing with wings outstretched to appear larger and to claim their share of the food. Being the hygienic birds that they are, they will often be found using a nearby waterhole or pool of water to thoroughly clean and preen themselves after a large meal.

HABITAT AND REPRODUCTION

The Cape vulture roosts and nests in large colonies on cliff faces in or near mountains. Nests are constructed out of sticks lined with dry grass, and breeding usually takes place between April and July. A single egg is laid and both parents, who mate for life, share the responsibility of incubation and feeding the young. Incubation lasts for 54 days, and the chick fledges at about 140 days after hatching.

DISTRIBUTION

The Cape vulture is restricted to southern Africa with main colonies in South Africa and Botswana. They are now extinct as a breeding species in Namibia, Zimbabwe and Swaziland.

APPEARANCE

Cape vultures have a creamy-buff body plumage with black flight and tail feathers. They have a black beak, honey-coloured eyes and a naked, blueish throat. Juveniles are darker brown with pink neck skin and brown eyes.

• Body length: 96-115 cm

• Wingspan: 226-260 cm

• Weight: 7-11 kg

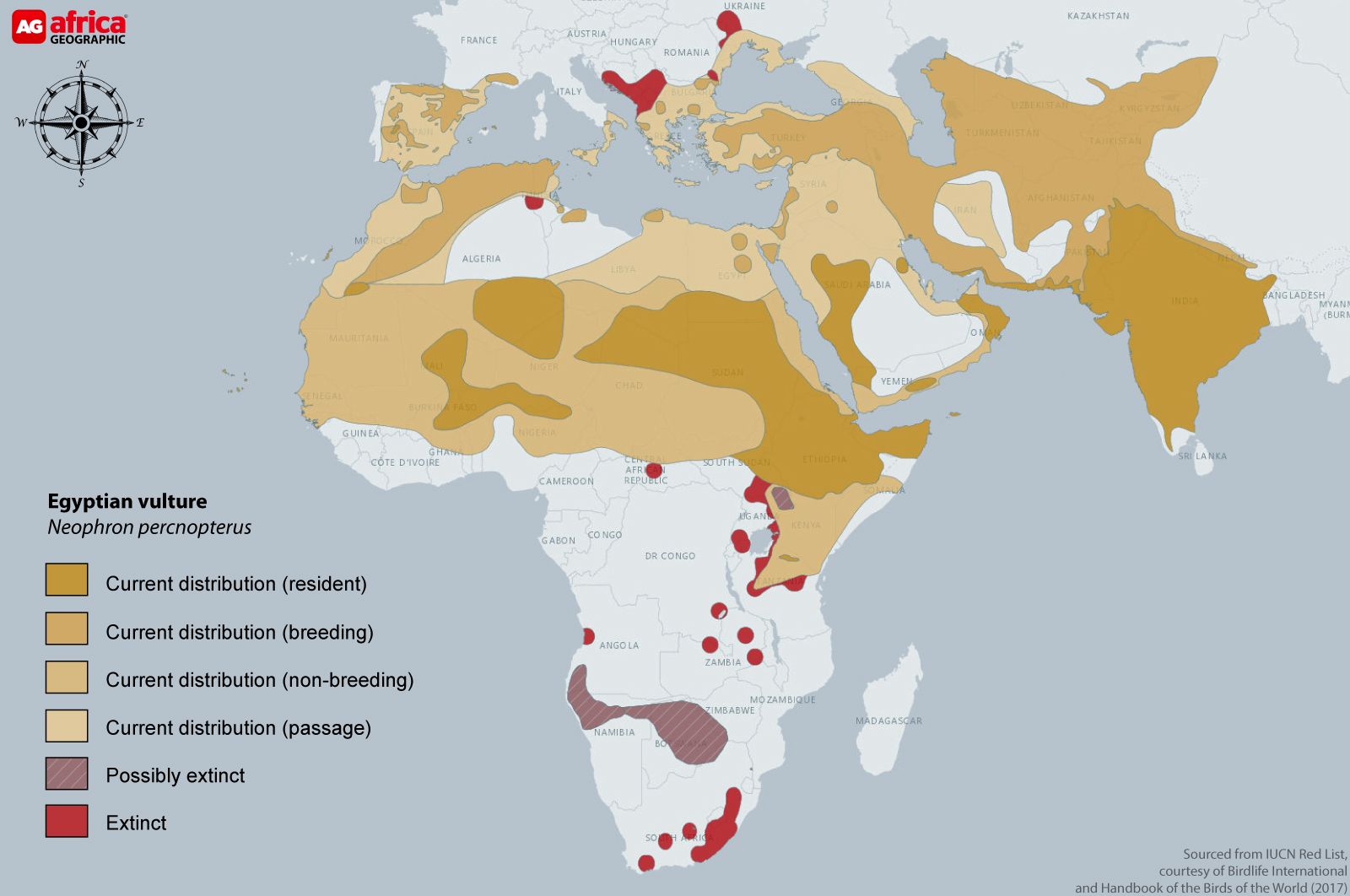

EGYPTIAN VULTURE – ENDANGERED

The Egyptian vulture, also known as ‘pharaoh’s chicken’ (Neophron percnopterus), once lived in abundance along the Nile River and were depicted in hieroglyphics by the Ancient Egyptians. Now they are listed as ‘Endangered’ and, according to the IUCN Red List, the population is estimated at 12,000-38,000 mature individuals. Threats to their population include collisions with power lines, hunting, intentional poisoning, lead poisoning from ingesting ammunition in carcasses, and pesticide accumulation.

They are opportunistic feeders with a varied diet which includes carrion, garbage (such as old vegetable matter), eggs, insects, and occasionally small birds, reptiles, and mammals. These vultures are one of the few bird species known to use tools. To break open eggs, they will drop small stones onto the egg until it cracks. They have also been observed using sticks to gather and roll wool, which they then use as a lining in their nests.

HABITAT AND REPRODUCTION

Egyptian vultures nest on cliff ledges, in caves, or rocky outcrops. The nest is made out of sticks and lined with a variety of material, from wool and animal hair to rags and grass. The female usually lays two eggs per year and incubation is done by both parents for 39-45 days. Once hatched, both chicks are looked after until they fledge at around 70-85 days old.

DISTRIBUTION

Egyptian vultures are found in northern Africa, southwestern Europe, and the Indian sub-continent.

APPEARANCE

Egyptian vultures have a yellow, bare-skinned face, white to pale grey plumage and black flight feathers. The beak is yellow with a black tip. Juveniles are largely dark brown with a contrasting area of pale buff.

• Body length: 54-66 cm

• Wingspan: 146-175 cm

• Weight: 1.6-2.4 kg

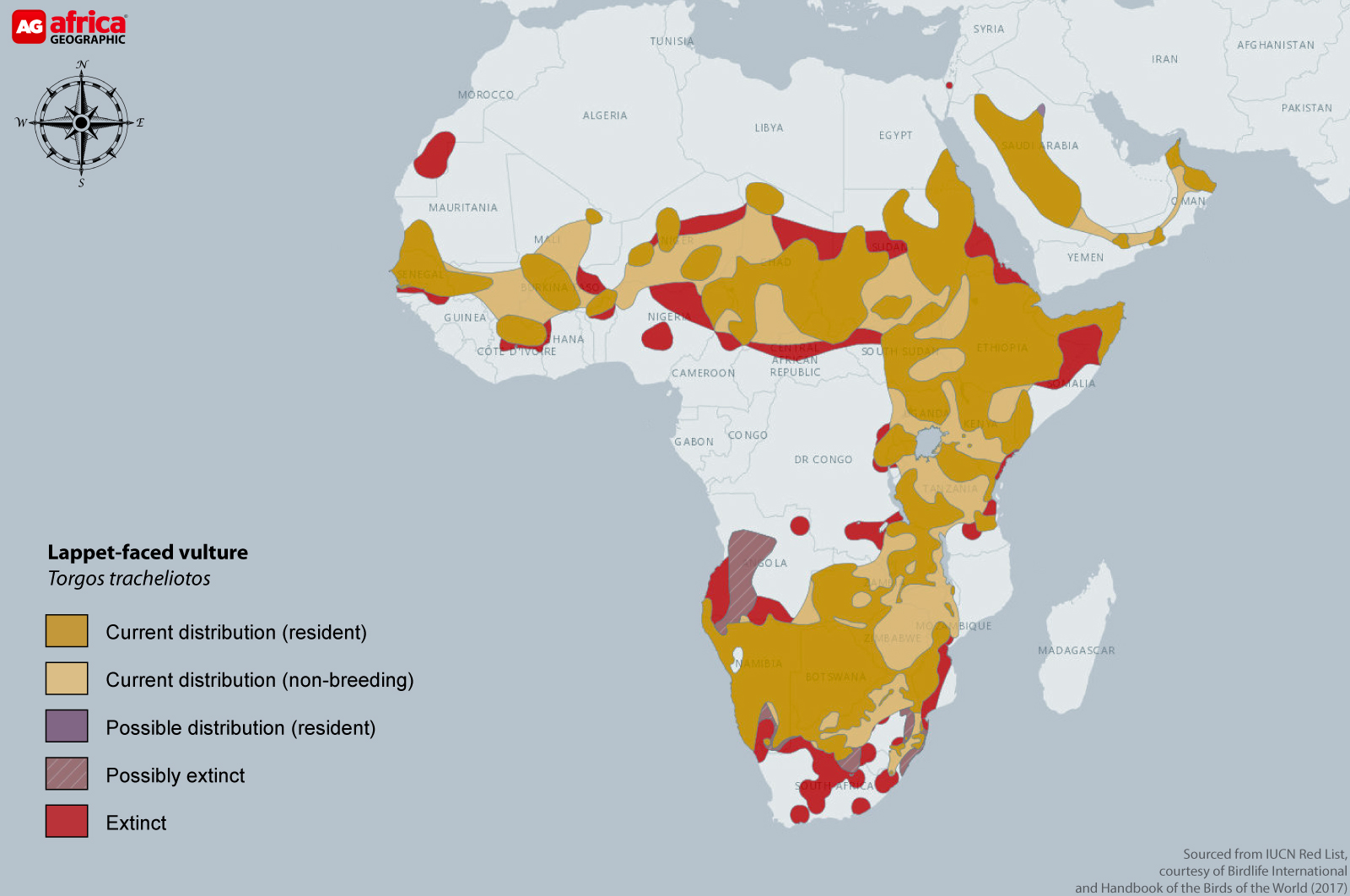

LAPPET-FACED VULTURE – ENDANGERED

The lappet-faced vulture, also known as the Nubian vulture (Torgos tracheliotos) is listed as ‘Endangered’ by the IUCN Red List and only a small, very rapidly declining population of approximately 5,700 mature individuals remain. Their decline is primarily due to poisoning and persecution, as well as ecosystem alterations.

They are enormous vultures and are considered the most powerful and aggressive of the African vultures. Dominant at carcass sites, they are capable of tearing into tough hides and muscles, thus benefitting less powerful vultures which then have access to the soft tissue of the carcass.

HABITAT AND REPRODUCTION

Lappet-faced vultures inhabit dry savannah, arid plains, deserts with isolated trees and open mountain slopes. They breed at the top of tall thorny trees such as acacia, balanites and terminalia trees. The female lays a single egg in a nest made of twigs (the same one is used year after year) and shares the responsibilities of incubation and feeding with her lifelong partner. The incubation period is 54-56 days, and chicks fledge between 125-135 days.

DISTRIBUTION

The lappet-faced vulture is endemic to the Middle East and Africa, where it is found from the southern Sahara to the Sahel, down through East Africa to central and northern South Africa.

APPEARANCE

This vulture has the largest wingspan of any other vulture in Africa. They have a short neck with a powerful, sharp beak. They have a bald, pinkish-skinned head and lappets (the folds of skin on the sides of its head) which can change different shades of colour depending on the mood and temperature. They have dark brown or black feathers, with white legs, as well as a white bar on the underside of the wing. Juveniles are mostly brown with few down feathers on the head.

• Body length: 95-115 cm

• Wingspan: 250-290 cm

• Weight: 4.4-8.5 kg

FINAL THOUGHTS

“All in all, vultures are such gentle, charismatic creatures that are fascinating and mesmerising to watch, research and conserve. They are noble and forgiving creatures that simply want to be – i.e. live, reproduce and be left alone. One cannot forget that vultures play a significant role in preventing the spread of diseases by efficiently and effectively consuming carcasses that would otherwise be left to decompose in our environment.

“Each species has their unique character traits and their own inner beauty which defines them and their individualities. They are exquisitely beautiful with their piercing intelligent eyes that look deep through your soul with a longing to be understood and loved.” ~ Kerri Wolter (Founder/CEO of VulPro)![]()

ABOUT VULPRO

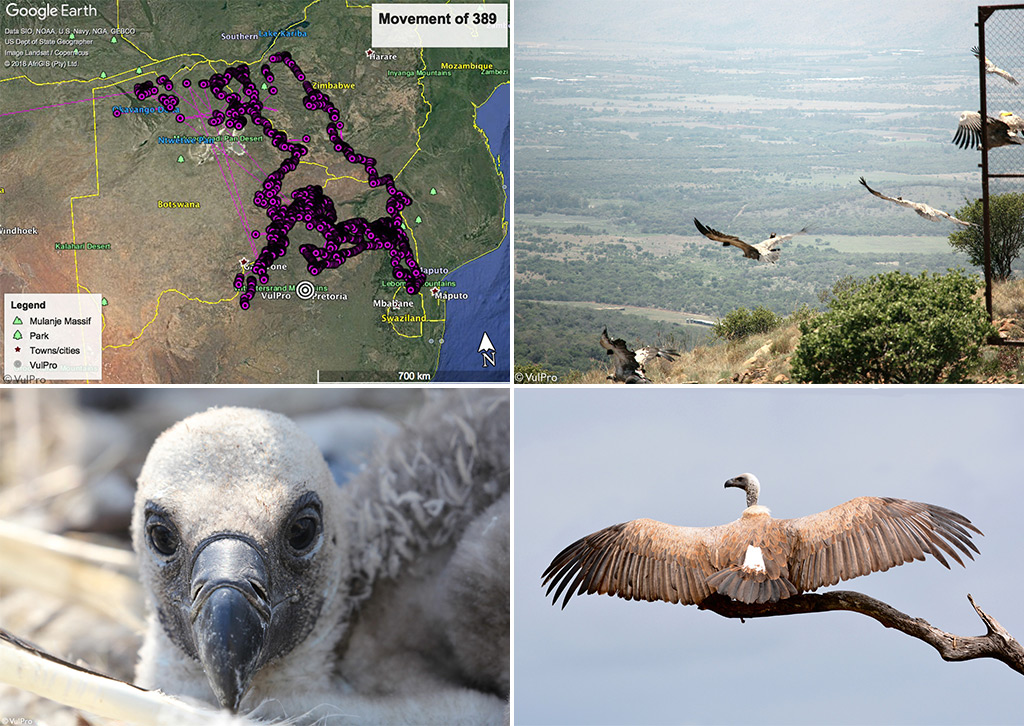

Africa is facing a vulture crisis, and we could lose some of our vulture species within our lifetime. For this genuine reason, VulPro was established in 2007 to address the catastrophic declines of vultures across the continent with special emphasis initially being on the Cape vulture as southern Africa’s only endemic vulture species. However, this focus has shifted to include all African vulture species, with a multifaceted and adaptive management approach encompassing both in-situ and ex-situ conservation strategies.

VulPro is leading the way, with innovative and adaptive methods, to saving Africa’s vultures. Vulpro recognises that every person counts and every person can affect change and contribute to the survival of the vulture species. Their mission is to advance knowledge, awareness and innovation in the conservation of African vulture populations for the benefit and well-being of society.

VulPro conducts and facilitates educational talks at its rehabilitation and educational centre in Hartbeespoort, as well as at external, formal and informal venues and with groups of varying demographics, ages, interests and expertise.

Their objectives are to save vultures from extinction through the following conservation strategies:

• Vulture rehabilitation

• Monitoring distribution and foraging ranges throughout sub-Saharan Africa

• Monitoring wild vulture populations and breeding success

• Veterinary and ecological research related to vultures

• Conservation breeding and reintroduction programmes

• Public education and awareness programmes

There are several ways to GET INVOLVED and MAKE A DIFFERENCE, via volunteering experiences and donations.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()