The most mysterious antelope in Africa

In the gloom of an African rainforest, hulking figures lurk in the shadows between the towering trunks. The air is filled with the relentless sounds of life – chirping crickets, melodious birds and chattering primates – yet the Delphic shapes are silent but for the odd soft snort. Now and again, a break in the canopy lets through a slice of a sunbeam, lighting up a blaze of red fur. Silent, secretive, and shy, the bongo is one of Africa’s more mysterious characters.

The basics of bongos

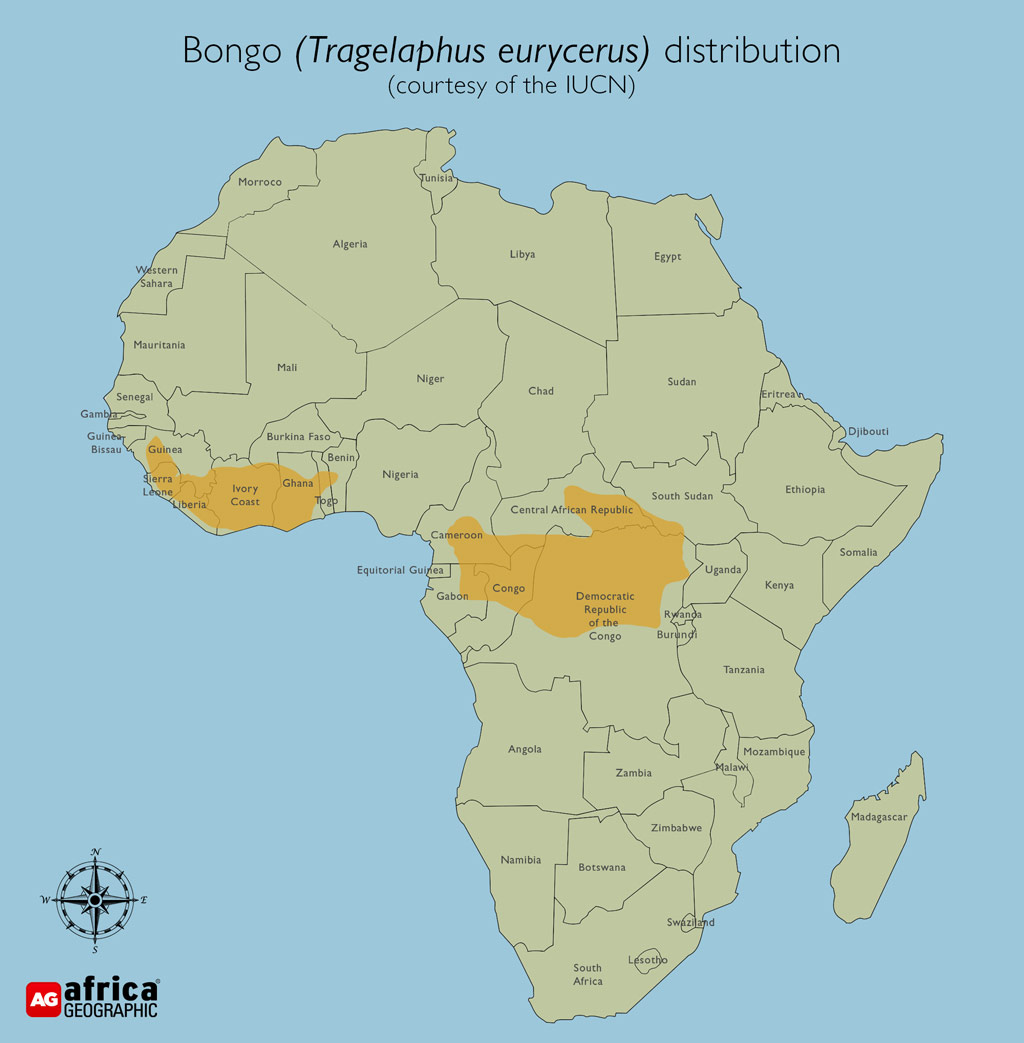

Surprisingly, few people know of the striking bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus), despite it being one of Africa’s larger and more distinctive antelope species. This partly concerns their preference for the tropical jungles and dense forests, as well as a somewhat distrustful approach to people. There are two recognised subspecies: the western/lowland bongo (T. eurycerus) in disjunct populations in West and Central Africa and the critically endangered eastern/mountain bongo (T. e. isaaci) in small, fragmented populations in Kenya.

The bongo’s bright auburn coat is perhaps its most distinctive feature, along with the white stripes that run down the flanks from the short dorsal crest. These stripes are believed to act as camouflage in dense vegetation by breaking up the animal’s outline. Bright white chevrons decorate the face and chest, emphasising body language cues in gloomy environments. Unusually for a forest-dwelling antelope, bongos are massive and are one Africa’s heavier antelope species. Though the males and females are similar in height, and both have horns, the males are considerably stockier and darken with age. It is not uncommon for older male eastern bongos to take on a rich mahogany colour.

Anyone familiar with nyala, sitatunga or kudu can immediately see the family resemblance when looking at the bongo. This tribe is known as the Tragelaphini, or spiral-horned antelope tribe and includes nine different species in two genera (for now – genetic analysis is ongoing). Despite their iconic “antelope look”, the spiral-horned antelopes belong to the subfamily Bovinae, and their closest relatives are bovines such as buffalos, bison and wild cattle. Within the tribe, bongo and sitatunga can hybridise and produce fertile offspring (known as a “bongsis”), reinforcing the theory that the two are most closely related.

Quick facts

| Shoulder height: | 1.1-1.3 metres |

| Mass: | Males: 220-405kg |

| Females: 150-235kg | |

| Gestation: | 285 days |

| Conservation status: | Western bongo: Near Threatened |

| Eastern/mountain bongo: Critically Endangered |

Being a Tragelaphid…

Apart from shared physical similarities like white stripes, enormous ears, and lyre-shaped horns, the bongo and other members of the Tragelaphus genus share several behavioural similarities. These antelopes, including nyalas, bushbucks, sitatungas and kudus, all rely on concealment in dense vegetation and are not known for their running stamina. When hiding fails and bongos are forced to flee from a predator, they will do so only as far as necessary before attempting to obscure themselves in a thicket once again. The massive ears and enormous eyes – attractive characteristics of all members of this genus – are likely an evolutionary necessity to this veiled approach to predator avoidance. All the better to see and hear them with…

Bongo behaviour

Bongos are primarily nocturnal or crepuscular, though occasionally active during the day. They spend most of their time browsing, sometimes supplementing meals of leaves and small plants with mouthfuls of fresh grass. Studies have shown that bongos require permanent access to both water and salt. Of the herds studied within the Dzanga-Ndoki National Park in the Central African Republic, the focal points of their home ranges were all found to be clearings around waterholes and mineral licks. Small herds (seldom more than twenty individuals) of females and their youngsters hid in the forests during the day before emerging at dusk to drink and eat the mineral-rich clay soils (geophagy).

Unlike females, adult males are usually solitary once they reach sexual maturity at around two years old. Though their cryptic natures mean that bongos are relatively understudied across much of their natural distribution, research has shown that they are seasonal breeders in certain parts of their range. During these times (usually around October to January), the bulls will approach and interact with the herds searching for a receptive female. Naturally, competition with other males is likely in the mating season. Like other members of the Tragelaphus genus (especially nyalas), the bulls will avoid conflict if possible, relying on a combination of piloerection, lateral presentation, and slow-motion movements to intimidate rivals. When this fails, male fights can be vicious, prolonged, and potentially fatal.

Roughly nine months after the victor of such battles has claimed his prize, the female will give birth to one calf. These calves are hidden for at least a week before they are introduced to the rest of the herd.

From the west side to the east side

Overall, the bongo is classified as ‘Near Threatened’ on the IUCN Red List, but the distinction between the western and eastern subspecies of bongos has significant conservation ramifications. Both subspecies are under threat due to habitat loss and bushmeat hunting. However, numbers of eastern/mountain bongos have fallen below the minimum level necessary for a viable, sustainable population. There are believed to be fewer than 140 individuals confined to just five fragmented habitats in Kenya: Mount Kenya, the Maasai Mau Forest Complex, the SW Mau Forest, the Eburu Forest and the Aberdares Mountains. Illegal logging continues to reduce already limited available habitat, poaching and predation by lions contribute to declining numbers, and disease transmission from cattle has grave implications for their future survival.

The only things standing between the eastern subspecies and extinction in the wild are multi-pronged conservation efforts to preserve their remaining habitats and maintain genetic diversity. The bulk of this work falls to the Kenyan National Bongo Task Force and the Bongo Surveillance Project. Strategies to save the subspecies include the creation of the Mawingu Mountain Bongo Sanctuary and the gradual rewilding of captive-bred individuals. Their bright colours and placid temperaments have made bongos popular in zoos and private collections. More eastern bongos are in captivity in North America than in the wild. However, these animals are unfamiliar with the Kenyan environment and climate, excessively tame, susceptible to native diseases and predator naïve. It takes many years of intensive work before they or their offspring are ready to enter the wild.

The bongo sasa

Interestingly, one major factor that has played a role in keeping the western bongo safe from the worst effects of bushmeat hunting is a superstition that surrounds them. In Gabon, particularly, the bongo is said to be suffused with sasa – a kind of evil power in certain animals and plants that works hand in hand with witchcraft. The sasa of the bongo is sasa a eye duru, which translates as sasa – “which is heavy”. Many believe that those foolish enough to hunt a bongo risk falling victim to seizures and madness, which can only be treated with rigorous cleaning rituals.

This superstition has probably helped reduce the number of bongos killed for bushmeat, but recent research suggests that these taboos are becoming less prevalent.

Where can I see one in the wild?

The best places to see bongos in the wild are in the Republic of the Congo, in either Odzala-Kokoua National Park or Dzanga-Sangha National Park. Staking out one of the baïs (forest clearings) at sunset offers the strongest chance of catching them as they leave the forest to come and drink.

Want to see bongos in the wild? Get in touch with our travel team to discuss your bongo-seeking safari – details below this story.

Enjoying the rare experience of seeing a bongo in the wild can be nothing but rewarding. The bongo is unequivocally one of Africa’s most graceful and attractive antelope, yet their shy natures and love of obscurity have kept them largely off the safari radar.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()